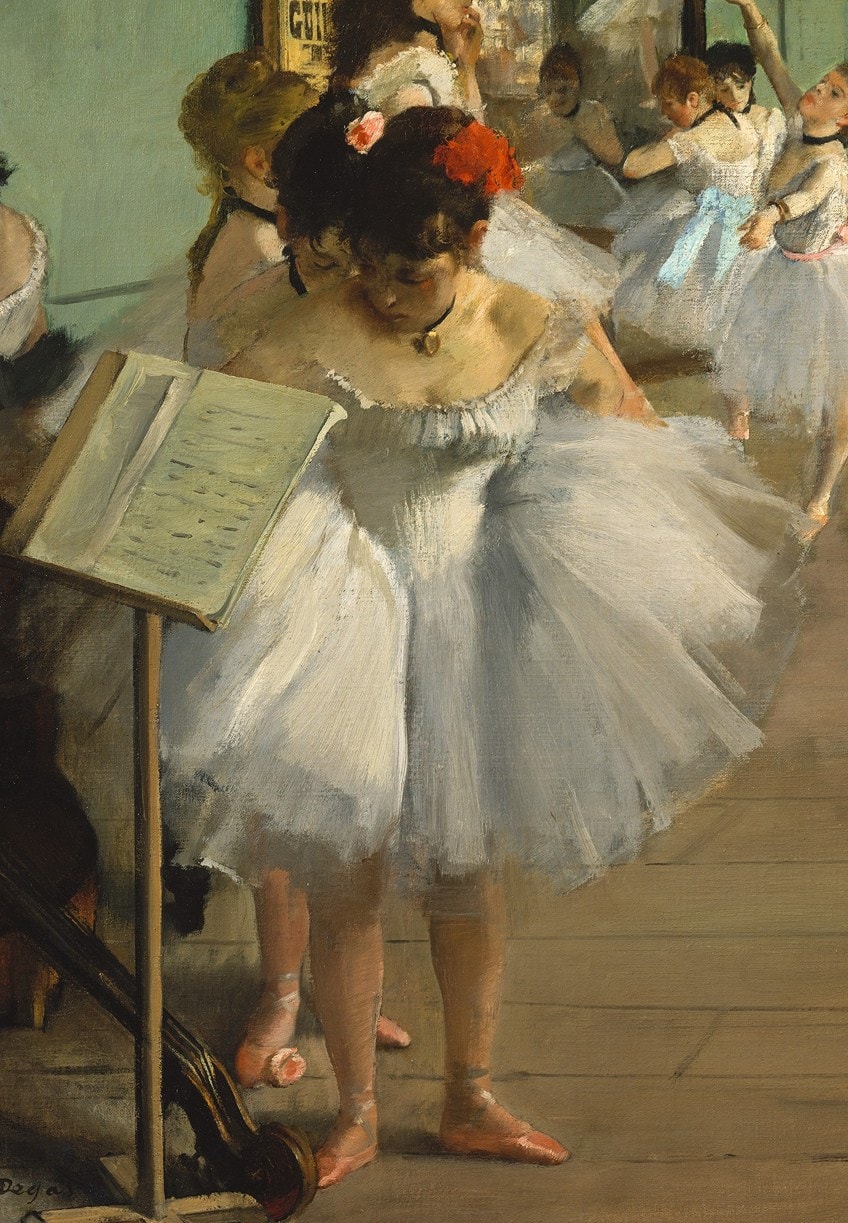

“The Dance Class” Edgar Degas – Analyzing the “Dance Class” Painting

Imagine walking into a class filled with ballerinas practicing and chatting with one another completely unaware that you walked in. This is what we see in so many of the paintings by the Impressionist Edgar Degas. He gave us insider views of the goings-on in the dance studios of the Paris Opera during the 19th century, which is what we will discuss in the article below, specifically looking at The Dance Class (1874) painting.

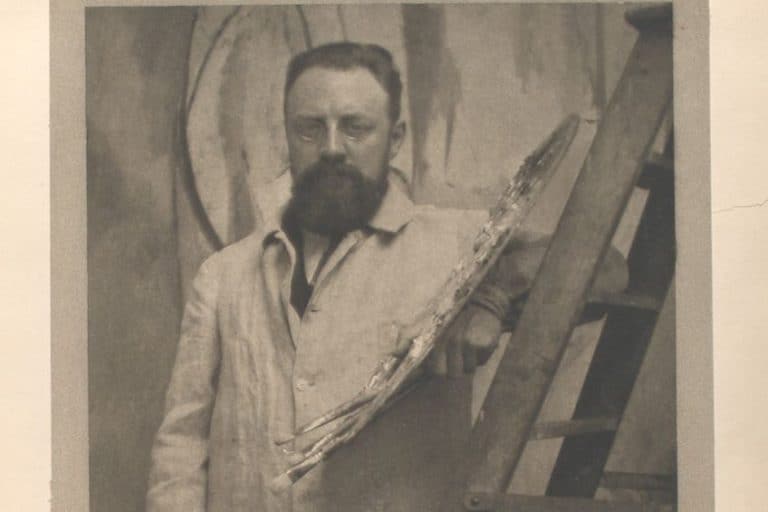

Artist Abstract: Who Was Edgar Degas?

Born on July 19, 1834, Edgar Degas was born as Hilaire Germain Edgar De Gas but changed his surname to Degas when he was older. His parents were from different countries, notably New Orleans and America. He enjoyed art from an early age and wanted to pursue studies in it after he turned 18.

His father encouraged him to study Law, of which he enrolled in 1853, but in 1855 he started studying at École des Beaux-Arts. He studied Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ art style under Louis Lamothe. Degas traveled to Italy during his twenties as well as stayed with his brother, René, in New Orleans from 1872 to 1873. He lived and died in Paris in 1917.

The Dance Class (1874) By Edgar Degas in Context

The Dance Class painting by Edgar Degas was among one of his finest examples from the Impressionist art movement from Paris. However, although Degas has been known as an Impressionist, he never fully identified as one. This, and more, we will explore in the Edgar Degas The Dance Class analysis below.

Below, we will start with the contextual analysis, giving a brief overview of the Impressionist movement and why Degas painted his famous dance class scenes. We will then provide a formal analysis taking a closer look at The Dance Class painting itself, shining a light on the subject matter and Degas’ use of stylistic elements like color and brushwork, which was such a prominent part that made many Impressionistic paintings as we have come to understand them over time.

| Artist | Edgar Degas |

| Date Painted | 1874 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Genre | Genre painting |

| Period / Movement | Impressionism |

| Dimensions | 83.5 x 77.2 centimeters |

| Series / Versions | It has a twin painting titled The Ballet Class (c. 1871 – 1874) housed at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

| Where Is It Housed? | Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET), New York City, United States |

| What It Is Worth | It was initially bought for Fr 5, 000 in 1874 by Jean-Baptiste Faure, who commissioned the artwork. |

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

Before we look at some of the possible reasons why Degas chose to create The Dance Class painting, of which there were also many others with the similar subject matter, including the “twin” painting called The Ballet Class (c.1871 to 1874) now housed in Paris at the Musée d’Orsay, we will provide a brief historical overview of the Parisian art scene during the 19th century and the importance of Impressionism versus the traditional Academic art of the Salon.

Some other examples from Degas’ dancing and ballerina themed paintings include The Dancing Class (1871), Foyer de la Danse (1872), Ballet Rehearsal (1873), Rehearsal on Stage (1874), Fin d’Arabesque (1877), and The Singer with the Glove (1878), among others.

The Importance of Impressionism

During the 19th century in Paris the main mode for artistic exhibitions, which were primarily paintings, was through the Salon. The Salon was part of the Academy of Fine Arts in France, in French known as the Academie des Beaux-Arts. The Salon was exhibited from 1667 and was an annual and biennial exhibition.

Due to the conservative and Academic practices and rules of how art was supposed to look, including how paintings were distinguished according to a hierarchy of standards, of which History paintings – usually of religious or mythological subjects – were at the top, many artists could not exhibit their works at the Salon.

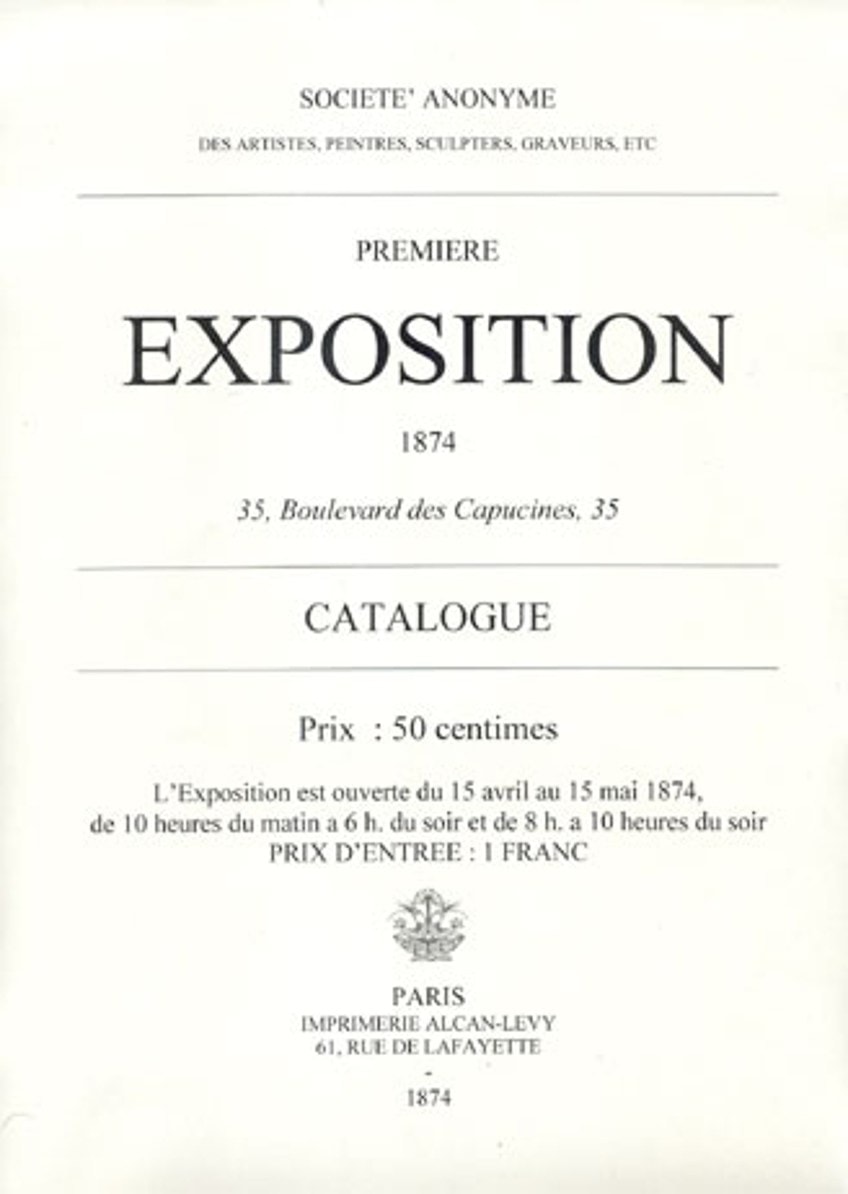

Among these were the Impressionist painters like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, as well as Edgar Degas; they eventually started their own exhibition through their group called the Sociéte Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (“Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers”).

The group of artists started exhibiting during 1874 in the Frenchman, Felix Nadar’s studio, he was a photographer and writer among other accolades. There were reportedly around 30 artists who exhibited here.

A few well-known artists did not choose to join this anonymous society exhibition, namely, Édouard Manet, whose Le déjeuner sur l’Herbe (1863) painting made quite the impression in the Salon exhibition due to its non-traditional style and subject matter.

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (“Luncheon on the Grass”) (1863) by Édouard Manet; Édouard Manet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (“Luncheon on the Grass”) (1863) by Édouard Manet; Édouard Manet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Understanding that the Salon exhibitions were important, if not crucial, for artists of the time will highlight how controversial the Impressionists’ exhibitions were because they went against convention and tradition and paved their own road. The group of artists exhibited until around 1886, having had around eight exhibition shows.

The Impressionists’ style was vastly different from that of the Academic painting styles before them.

Artists painted in the en plein air style, which means “outdoors” in French, and depicted scenes of everyday life and people. This was based on a new way of perceiving life and its transitory moments, translating it with bold areas of color. This color would in turn depict how the light fell on the subject matter painted.

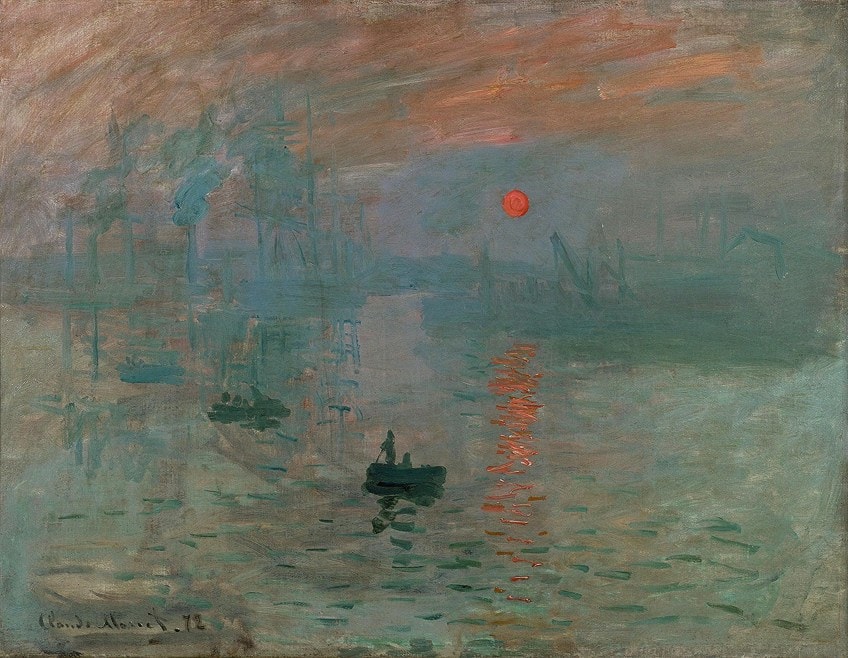

It is important to note that the Impressionists were all different in their individual styles and there were artists who did not identify as “Impressionist”, which is a term given to the group by the art critic Louis Leroy after he viewed Impression, Sunrise (1872) by Monet. Another term the Impressionists went by was the “Independents”.

While some Impressionists painted en plein air style, others explored the everyday lifestyles, postures, and poses of people engaging in a variety of acts from people bathing, frequenting cafés, and as we see in Degas’ artworks, ballet dancers either rehearsing, stretching, or conversing with other dancers.

He depicts a moment in time, in tune, and in the song of various female dancers and singers. He was remembered for always studying their movements that would flow in natural ease, also spotting the spontaneous aspects of how a dancer would move.

Degas and Dance

Degas loved to dance and this was a theme in most of his paintings. He apparently visited the Paris Opéra, the Palais Garnier, on numerous occasions to watch the Ballet shows and visited behind the scenes where the girls would rehearse. For Degas, the ballet world, its dancers, and their many movements became his subject matter.

He is famously quoted from his discussion with Ambroise Vollard, who was an art dealer in Paris, talking about how people perceived him; he said that people called him “the painter of dancing girls”. He continued to say that “it has never occurred to them that my chief interest in dancers lies in rendering movement and painting pretty clothes”.

The Dance Class painting was commissioned by Jean-Baptiste Faure, who was an Opera baritone, in 1873. Faure also collected art and Degas’ paintings constituted a large part of his collection. When Degas completed the painting for Faure in 1874, the art collector also loaned the painting to the Impressionist exhibition in 1876, which was the Impressionists’ second exhibition. The painting was also titled Examen de danse.

Another notable figure frequenting Degas’s dance paintings is Jules Perrot. He was a ballet dancer as well as a ballet master. His presence in Degas’ paintings indicates that he was instructing the ballet dancers. We see Perrot’s same countenance in Degas’ other painting The Ballet Class.

Degas and Photography

Photography was another important influencing factor on Degas’ artworks, especially relating to the composition of his paintings. During the time Degas painted photography was a new mode of expression that enabled many to depict the world and people around them. In Paris, photography was largely made popular by Louis Daguerre, which he introduced in 1839.

It was not only for Degas that photography became a new medium, but it was also new for the Impressionists. It upended the notions of what art should be, and two important aspects of this were the utilization of the cropped image and spontaneous representations.

We will find in numerous paintings by Edgar Degas that depict the element of cropping and capturing the natural and unposed poses of people, for example, Three dancers in a practice room (1873), Place de la Concorde (1875), L’Absinthe (1876), Dancers in Pink (1876), Ballettprobe (1875), and many more.

“The Painter of Dancing Girls”: Is There More to the Story?

There has been wide debate around why Degas painted his famous ballet dancers as it possibly alluded to another, “darker”, aspect of female dancers. Some sources suggest that the ballet dancers were also involved in sexual liaisons with wealthy men, otherwise knowns as “subscribers” to the theatre, referred to as abonnés in French. The rooms behind the stage, foyer de la danse, were reportedly where the dancers would meet these men. These rooms were also utilized for rehearsals before a show.

The men would offer forms of financial support to ballerinas who were there that needed the work and additional support.

With this, the ballerinas tended to succumb to the men because they would be given a better lifestyle and sometimes even a better role in the ballet. This reinforces the adage given to Degas as “the painter of dancing girls”; he painted more than dancing girls and showed us, the viewers, what happened when the curtain closed. Another example of this is in The Star (L’Étoile) (1878) where we see the ballerina’s “patron” standing towards the left behind the curtain.

Formal Analysis: A Brief Compositional Overview

Below we open the curtain, so to say, and look at Edgar Degas’ The Dance Class analysis in terms of formal elements, for example, Degas’ utilization of paint as a medium as well as the perspective he painted from. While this composition is not on stage, it is in a rehearsal studio.

Subject Matter

In The Dance Class, Edgar Degas sets the scene by giving us an insider look at a few ballet dancers rehearsing while some sit along the periphery waiting to dance or have danced. Let us start from the foreground and move ourselves to the background.

In the foreground, towards the left, we will notice two ballerinas, the one in our view is standing with her head tilted to her left (our right).

She is busying herself with her tutu, waiting for her friend behind her, who appears to help her fix or adjust something on her tutu. We only notice her hair, upper shoulders, and face as she bends down. The two girls are unaware of us, the viewer, and are casually going about their business.

Further towards the middle-left edge of the composition is a girl wearing a black choker necklace, standing with her back to everyone. She appears to be reading a piece of paper, completely in another world and unaware of what is around her. Nestled between this girl and the two girls we mentioned we will notice another girl with blond hair standing and watching the scene in front of her, although we cannot see her face, but just the back of her head and upper torso.

Standing just a few steps away is a noticeably taller girl with dark brunette hair that is also hanging loose behind her. She appears to be staring out in front of her at the dancing instructor, who is Jules Perrot, but we will get to him shortly. Back to the tall girl, she stands with what appears to be her left hand’s fingers in or by her mouth, almost as a gesture of being distracted or preoccupied, listlessly fiddling with her fingers.

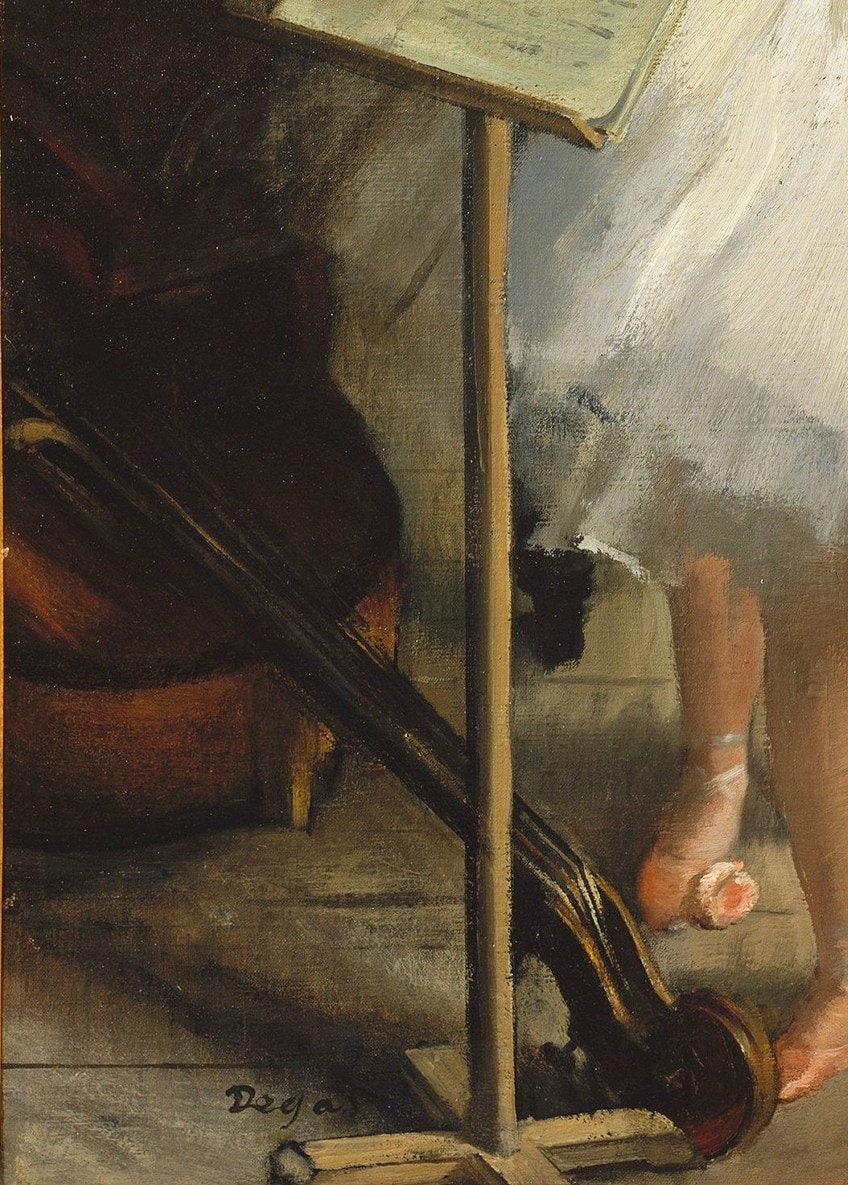

Additionally, in the bottom left corner, we will notice a cello placed on the wooden floor, lying at a diagonal angle, the top tip right near the ballerina’s pink-shoed foot.

There is also a wooden music stand with a piece of sheet music placed on top, the four-legged stand is placed in front of the cello’s top tip. We will also notice a piano here, of which the girl to the far left is resting her left elbow.

The central figure, which is more to the middle right edge of the composition, is the ballet master Jules Perrot. He is standing with his gray-haired head slightly tilted to his right, watching a ballet dancer as she rehearses before him. This head angle is referred to as a profil perdu, which means “lost profile” in French. This is when a person’s face is not completely visible, mostly visible from the back of the head. This is also a characteristic profile widely utilized.

Perrot is calm yet engaged in the activity, both his arms are lightly outstretched, his elbows bent, and his hands resting on his long wooden cane, which appears to be around three-quarters of his body’s length.

Perrot appears to be a short man, wearing a beige-colored suit and a red shirt underneath. We will also notice his black shoes with revealing white socks. There appears to be a white handkerchief peeking out from his left jacket pocket, the latter is quite long and hangs below his waistline.

The main dancer whom Perrot is observing appears mid-way between a pose, possibly a Piqué attitude pose. Her left arm is held out in front of her, her right arm is raised above her head while her right leg is lifted and bent out behind her, and she balances on her left leg whilst tilting her head to her looking upwards.

Moving further towards the background, we will notice various ballerinas sitting on the stands against the wall.

There are also other figures, possibly their mothers or caretakers, who seem to be waiting for the ballerinas to finish their rehearsal. Furthermore, the ballerinas sitting on the stands are all engrossed in their own activities, for example, a ballerina leans against the wall to the left with her hands behind her back and her head is tilted to her left watching as the ballerina next to her adjusts her black choker.

Near the bottom of the stands are two other ballerinas sitting, the one on the left is adjusting something on the front of her dress while the ballerina next to her on the right watches; both her feet are turned inwards, her arms resting on her lap with a semi-slouched back. This denotes a casual and relaxed posture, possibly even boredom.

This is something we see in the other ballerinas’ postures too, telling us they are waiting to finish rehearsal or waiting their turn.

There is a large mirror on the left-hand side wall reflecting not only the ballet dancers but also a window on the other side of the room, which is not included in Degas’ composition here. This window depicts an outside world and what appears to be part of the Paris cityscape. Degas gives us another sneak peek into the world outside.

An interesting fact about this mirror is that in Degas’ The Ballet Class, which was painted with a similar layout, there is a large opening in the wall leading into another section of the room where we see a window. This is in the same position where the mirror is in The Dance Class.

Next to the large mirror, on our left, is a poster on the wall where some of the words are legible, reading “GUIL”. This possibly alludes to the opera by Gioachino Rossini called Guillaume Tell, of which Jean-Baptiste Faure, who commissioned The Dance Class painting, played the character of Guillaume Tell.

There is an open space in the bottom right corner of the composition, which further adds to the idea of the spontaneity of the depiction of the scene.

It seemingly also leads us into the studio and suggests the naturalness of the scene, as if Degas was taking a photograph. This characteristic is well-achieved by Degas in his painting The Rehearsal (1874), where he crops the staircase on the left as well as the dancer on the right.

Color

Color is a prominent feature in Degas’ paintings, especially soft pinks, whites, and even blues – all belonging to the dancers. In The Dance Class, Edgar Degas depicts the interior with neutral tones, there are no bright splashes of color and the composition appears easy on our gaze.

The floor is an earthy brown and the walls appear in an earthy green. There are darker browns from the instruments in the foreground as well as the mirror’s wooden frame. The white outfits of the ballerinas seem to dominate the scene, with subtle hints of blues and pinks from their ribbons.

Here and there we see areas of red that break the more neutral tones, for example, the brighter red of Perrot’s shirt, the red flower in the girl’s hair in the foreground, and the red coat worn by the woman in the background.

As was the custom of the Impressionist style, we see the more expressive brushstrokes here, oftentimes making the subjects appear difficult to view in detail, which borders almost on “abstract” as some sources have suggested.

Finale: Degas Created a Sensory Experience

Edgar Degas did not identify as an Impressionist, he often referred to himself as a “Realist” and enjoyed painting scenes of everyday life and situations, often scenes of realistic occurrences in urban and essentially modern life.

We see this realistic outlook in many of Degas’ depictions of ballet dancers and their accompanying patrons, but nonetheless, Degas also depicted the beauty of form, color, and composition. He created a rich sensory experience through his various media of artworks, from drawings, paintings, as well as wax statues.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Painted The Dance Class?

The Dance Class (1874) is an oil on canvas painting by Edgar Degas, who was widely known as a painting in the Impressionism art movement during the 19th century. However, it should be noted that Degas did not identify as an Impressionist in the same way other Impressionists did. He painted more “realistic” aspects of modern life and not so much the en plein air, or “outdoors”, depictions that many artists enjoyed at the time.

How Many Versions of Degas’ The Dance Class Painting Are There?

Edgar Degas painted two paintings that appeared very similar, namely The Dance Class (1874), housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) in New York City, and The Ballet Class (c. 1871 to 1874) housed at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Both paintings were commissioned by Jean-Baptiste Faure, but Degas apparently started working on The Dance Class, which he gave to Faure.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““The Dance Class” Edgar Degas – Analyzing the “Dance Class” Painting.” Art in Context. December 3, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/the-dance-class-edgar-degas/

du Plessis, A. (2021, 3 December). “The Dance Class” Edgar Degas – Analyzing the “Dance Class” Painting. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/the-dance-class-edgar-degas/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““The Dance Class” Edgar Degas – Analyzing the “Dance Class” Painting.” Art in Context, December 3, 2021. https://artincontext.org/the-dance-class-edgar-degas/.