Salvador Dalí – The Archetypal Surrealist

Spanish painter Salvador Dalí was renowned for his work within the Surrealism movement. Salvador Dalí’s artistic oeuvre includes painting, cinema, sculpting, photography, and design, which he worked on alongside other artists at times. Dreams, the unconscious, sexuality, spirituality, technology, and his innermost personal connections are all major topics in Salvador Dalí’s paintings. To the dismay of all those who appreciated his artwork and the chagrin of his opponents, his volatile and extravagant public behavior often drew more attention than Salvador Dalí’s artwork.

Table of Contents

The Biography of Salvador Dalí

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Date of Birth | 11 May 1904 |

| Date of Death | 23 January 1989 |

| Place of Birth | Catalonia, Spain |

Salvador Dalí’s aspirations to construct a pictorial lexicon competent at representing his visions and dreams are based on Freudian philosophy. These are among the stunning and now universal artworks that helped him attain immense popularity throughout his career and beyond. The obsessional subjects of erotica, mortality, and deterioration pervade the Spanish painter’s oeuvre, demonstrating his knowledge of and assimilation of psychoanalytic concepts of the period.

Salvador Dalí’s artwork contains a lot of ready-made symbolism, ranging from obsessive and animal themes to theological symbols, and also leans on a lot of autobiographical content and memories of childhood.

To better understand Dalí’s immensely complicated and charismatic artworks, these childhood influences, and to answer questions such as “How did Salvador Dalí die?”, let us take an in-depth dive into this Salvador Dalí biography.

Childhood

The Spanish painter was born to a well-off family in Figueres, a little village outside of Barcelona. His larger-than-life personality developed amid his enthusiasm for art from a young age. He is known to have had chaotic, frenzied, rage-filled tantrums regarding his family and friends.

He found tremendous influence in his early surroundings in Catalonia, and many of its vistas would become recurrent subjects in his later significant pieces.

His parents nurtured his childhood interest in painting. He started sketching instruction when he was ten years of age and attended the Madrid School of Fine Arts in his mid-adolescence, where he dabbled with Pointillist as well as Impressionist techniques. He lost his mother to cancer when he was only 16 years old, which he describes as “the hardest trauma I had ever suffered in my entire life.”

His father presented a solo exhibit of the adolescent creator’s artistically superb charcoal sketches at the family residence when he was 19 years old.

Early Training

Salvador Dalí enlisted at the San Fernando School in Madrid in 1922. He matured there and grew to comfortably embrace his colorful and controversial image. His eccentricities were well-known and were initially more famous than Salvador Dalí’s paintings. He wore his tresses long and was adorned in the fashion of 19th-century English sophisticates, replete with knee-length britches, garnering him the moniker of a dandy.

He toyed with a number of approaches at the time, pursuing whatever piqued his unquenchable curiosity.

He became acquainted with and grew close to a group of prominent cultural figures that also included Federico Garcia Lorca, the poet, and the filmmaker Luis Bunuel. The residence itself was somewhat advanced, exposing Dal to some of the most influential thinkers of the day, including Einstein, Le Corbusier, Calder, and Stravinsky. However, Dalí was dismissed from the institution in 1926 for disrespecting one of his instructors during his last examination before graduating. Dal was out of school for several months after his expulsion.

He then embarked on a life-altering vacation to Paris. He paid a visit to Picasso’s workshop and drew inspiration from the Cubists’ work. He got fascinated by Futurist efforts to replicate movement and present objects from various viewpoints at the same time.

Dalí started researching Freud’s psychoanalytic principles as well as metaphysical artists and Surrealists, and as a result, he started adopting psychoanalytic ways of exploring the subconscious to develop images.

The Spanish artist would spend the next year delving into these ideas while attempting to devise a method of significantly reevaluating reality and modifying perceptions. Apparatus and Hand (1927), his first significant work in this manner, had the symbolic iconography and surreal environment that would become his distinctive painting hallmark.

Mature Period

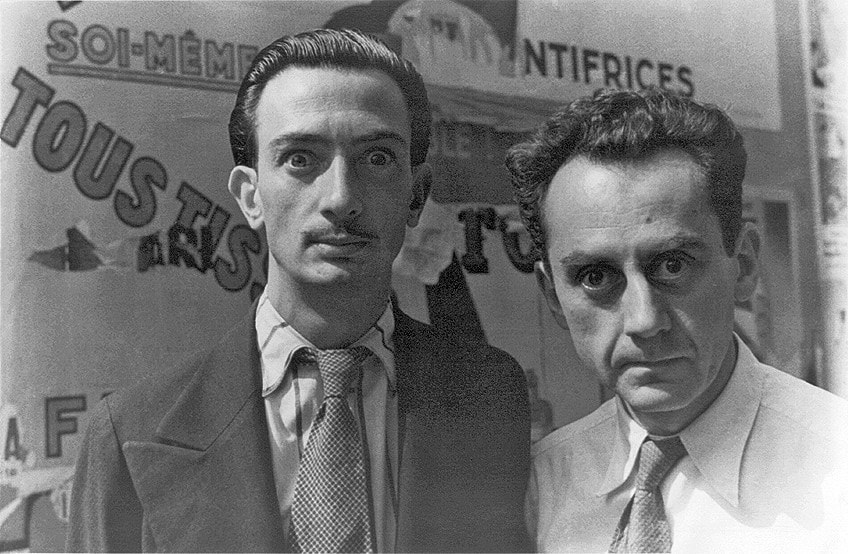

He then collaborated with Luis Bunuel on An Andalusian Dog, a cinematographic study on horrific cravings and illogical images, in 1928. The subject matter of the video was so graphically and ideologically offensive that he gained instant notoriety, generating quite a sensation among Parisian Surrealists. The Surrealists pondered bringing the Spanish into their fold and dispatched Paul Eluard and his wife Gala, to see him in Cadaques in 1929. This was the first occasion the artist and Gala met, and soon thereafter, the pair initiated a romance, which led to her separation from Eluard.

Gala was Dalí’s longtime, consistent, and most significant muse, his eventual spouse, and also his deepest interest, and professional manager. He traveled to Paris soon after this first encounter and was encouraged to join the Surrealism movement by André Breton. Dalí subscribed to Breton’s automatism thesis, which states that an artist curtails full command over the artistic process by letting the subconsciousness and intuitive voice direct the work.

However, he took this notion a level higher in the early 1930s by developing his own Paranoiac Critical Method, in which an individual may get into their subconscious via systematic illogical reasoning and a self-induced psychotic condition. After waking from a delusional condition, Salvador Dalí would produce “hand-painted fantasy images” of what he had seen, typically resulting in works of wildly unconnected yet accurately painted items that were often heightened by optical illusion methods.

He genuinely believed that audiences would interact with his artwork intuitively because subconscious communication was ubiquitous, and that “it communicates with the lexicon of the great essential constants, associated with sex intuition, the sensation of death, the tangible concept of the oddity of space – these essential components are uniformly reiterated in every human.”

He would utilize this style for the rest of his life, as seen in Salvador Dalí’s paintings such as The Persistence of Memory (1931). Salvador Dalí’s paintings were particularly expressive of his thoughts on the psychological problem of psychosis and its continued importance as a subject matter throughout the next several years.

He depicted corpses, bones, and allegorical items that conveyed sexualized anxieties of male role models and powerlessness, as well as motifs that alluded to worry over the passage of time. Many of Dalí’s most renowned works date from this prolific time.

While Salvador Dalí’s art was flourishing, his personal life was changing. Although he was encouraged and smitten with Gala, his father was less than thrilled with his son’s connection with a lady ten years older than he was. His early backing for his son’s creative growth was eroding as Dalí drifted more toward the avant-garde. The last blow came when the Spanish painter was reported in a Barcelona tabloid as stating, “Sometimes I spat for pleasure on my family’s photo.” Towards the close of 1929, the elder banished his child from the house.

The ethics of war were at the center of Surrealist disputes, and in 1934 Breton excused Dalí from the Surrealist group due to their contrary viewpoints on communists and fascists. In response to his expulsion, Dalí notoriously responded, “I am Surrealism.” For many years, Breton and several Surrealists had a difficult relationship with the Spanish artist, at times respecting him and at others distancing themselves from him.

Other Surrealist artists embraced him and remained close to him all through the years. In the years afterward, Salvador Dalí has traveled extensively and mastered more classical painting approaches inspired by canonized artists such as Jan Vermeer and Gustave Courbet, while his emotionally loaded subjects and subject matter have remained as unusual as ever.

His great reputation had spread so far that he was in high demand among the wealthy, well-known, and trendy. But Salvador Dalí’s actual magical moment certainly occurred that year when he met his idol, Sigmund Freud.

He was overjoyed to find, after painting his image, that Sigmund Freud had declared, “So far, I had been led to believe that the Surrealists, whom I had taken as my patron saint, were utterly mad. This young Spanish painter, with his frank, obsessive eyes and clear technical prowess, has persuaded me to reconsider.” He also met an important sponsor at this period, the rich British poet Sir Edward James. James not only bought Salvador Dalí’s art but also financially backed him for a couple of years and cooperated on several of Dalí’s most renowned pieces, such as The Lobster Phone (1936)

Salvador Dalí in the United States

The Spanish painter already had a foothold in the United States before his first visit. In 1934, the art dealer Julien Levy staged a show of Salvador Dalí’s paintings in New York, which featured The Persistence of Memory. Dal became a phenomenon when the exhibit was well-received. He initially visited the United States in the mid-1930s. And he kept ruffling feathers wherever he went, frequently arranging planned public appearances and exchanges that were early instances of his affinity for performing.

At one of these events, the pair costumed as the Lindbergh baby and his abductor and attended a masquerade event in New York. This produced such a commotion that he apologized in the newspaper, earning him scorn from the Parisian Surrealists.

While in New York, the artist also attended other Surrealist gatherings. He was exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art’s inaugural exhibition on Dada, Fantastic Art, and Surrealism.

He also caused quite a stir when he toppled over the projector during a screening of Joseph Cornell’s Surrealist films, famously seething “My film concept is exactly that, and I was planning to pitch it to somebody who would want to have it produced. I never took notes or told anybody about it, but it’s as if he took it.” Dali and his wife returned to America in 1940, following the destruction of the Second World War in Europe. During this time, he became extremely productive, broadening his profession beyond the visual arts to include a wide range of other creative pursuits.

He created jewelry, apparel, furniture, settings for plays and ballets, and even retail shop display windows. The Spanish painter’s quirky nature frequently took the spotlight in many of these endeavors; for example, when being assigned by the department shop Bonwit Teller, the artist was so enraged by alterations to his design that he slammed a bathtub through the front display case. They wanted to be famous and make a lot of money, so Hollywood was a logical choice for the pair.

They were not successful in their pursuit for movie stardom, but he was asked to create the design for the dream sequence in the film, “Spellbound” (1945), by Alfred Hitchcock. Furthermore, Disney collaborated with Dalí to make the cartoon “Destino”, but the production was halted due to financial issues after the war and was not realized until long later.

The Spanish Artist Returns to Port Lligat

The artist then bought a tiny coastal property in the neighboring fishing hamlet of Port Lligat after being evicted from the family home in 1929. He later purchased all of the surrounding properties, developing his land into a large palace. The couple returned to Port Lligat in 1948, making it their permanent residence for the following 30 years. Salvador Dalí’s artwork evolved throughout time. In addition to experimenting with various creative materials, Dal began to use optical illusions, negative space, graphic puns, and trompe l’oeil in his work.

Beginning in 1948, he would create one huge painting every year – his “masterworks” – that artistically engaged the Spanish artist for at least a year. His workshop included a unique opening in the floor that allowed him to lift and lower the massive canvases while he worked on them. Between 1948 and 1970, he created at least 18 similar pieces. He experimented with photography, as he did with many other artistic endeavors at the period.

Here, he collaborated with Philippe Halsman to make the renowned shot, Dal Atomicus (1948). Salvador Dalí’s paintings throughout the 1940s and 1950s were predominantly religious in nature, reflecting his lifelong fascination with the occult. “I am a predatory fish moving in two waters, the frigid water of art and the boiling water of science,” he famously declared. He intended to depict space as a subjective reality, which may explain why many of his artworks from this period depict objects and individuals at highly foreshortened angles.

He stuck to his “paranoiac-critical” style of spending long, difficult hours in the workshop and articulating his fantasies straight on canvas in frenzied bursts of intensity. The artist became rather solitary while working in his studio on paintings. Nonetheless, he continued to come out to stage stunts, or “manifestations,” that were as absurd as before.

These provocative performance-based exchanges informed the audience that the Spanish painter’s inner rascal was still alive and strong.

He drank from a swan’s egg while ants erupted from its shell in one, and drove about in a car stuffed to the brim with cauliflower in another. In 1962, following the release of his book The World of Salvador Dalí, he autographed personalized copies while linked up to a device that recorded his heart rate and electrical impulses in a Manhattan book shop. Buyers were given a signed hard copy of his book as well as a printout of his vital signs.

Later Period and Death

The latter two decades of the artist’s life would be the most stressful and mentally taxing. He bought a mansion in Pubol for Gala in 1968, and then in 1971, she began traveling there by herself for many days or even several weeks at a stretch, prohibiting him from arriving without her permission. Because he was frightened of being deserted, he grew depressed as a consequence of her absence.

Gala irreversibly injured the Spanish painter after it was found that she had endangered his condition in her mental decline by administering non-prescribed medications.

His physical injuries from Gala hampered his ability to create art till his death. Salvador Dalí suffered from depression again after her death in 1982 and is thought to have attempted suicide. During this difficult period, one of Dalí’s most significant accomplishments was the establishment of The Salvador Dalí Museum in Figueres. Dal said that rather than dedicating a single piece to the city, “Where else but in my own town could the most expensive and substantial of my artwork exist, where else but here?”

The artist worked diligently in the run-up to the museum’s opening in 1974, designing the structure and assembling the collection that would function as his legacy. The Spanish painter died of heart failure on the 23rd of January, 1989. He was laid to rest beneath the museum he founded in Figueres.

Salvador Dalí’s Art Style and Legacy

The Spanish painter exemplified the concept that life is the finest kind of art, and he mined it with such unrelenting passion, purity of goal, and dogged devotion to discovering and polishing his different hobbies and skills that his unprecedented effect on the art world is impossible to deny.

His drive to turn internal to the exterior unabashedly produced a body of work that not only expanded the principles of Surrealism and psychoanalysis on a global visual platform but also demonstrated freedom for people to accept themselves in all our human beauty, with all our imperfections.

Legacy

He opened up a world of options for artists trying to integrate the personal, enigmatic, and emotive into their works by offering us visual depictions of his visions and the inner world left bare, via fine draftsmanship and masterful painting methods. These ideas were integrated and changed by Abstract Expressionists in postwar New York, who employed Surrealist tactics of automatism to convey the subconscious via art, only now using motion and color.

Dalí’s use of dramatically juxtaposed found elements in sculpture helped loosen the discipline from its more conventional bones, paving the way for renowned Assemblage creators like Joseph Cornell. His impact may still be seen today in artists painting in Surrealist techniques, others in modern visual arts circles, and all throughout the digital arts and animation spectrums.

His unconventional and enigmatic physical presence in the world created the door for artists to conceive of themselves as trademarks. He demonstrated that there was no major distinction between the man and the artist. His utilization of avant-garde movie-making, controversial live performance, and arbitrary, strategic interplay brought his artwork to life in many ways that painting did not: instead of the audience simply looking at a brilliant work that conjured up great curiosity, they would be “jabbed” in real life by an incarnation of the artist’s dreams intended to unnerve and elicit a reaction.

This was later found in artists such as Yoko Ono. Andy Warhol would go on to create his own character, atmosphere, and crew, much like numerous other 20th-century artists. Artists are practically expected to be as visible and socially intriguing as their artistic work in the current media milieu.

Dalí’s also pioneered the notion that art, artists, and creative aptitude might transcend several mediums and become valuable commodities. His extensive ventures into disciplines spanning from fine art to clothing to jewelry to commerce and theatrical design established him as a successful businessman as well as an artist.

Art Style

Unlike mass commercialization, which is typically derided in the art world, his hand touched so many different objects and locations that anybody around the globe might possess a piece of him. Today, famous architects such as Frank Gehry make unique rings and necklaces for Tiffany, while innovators such as John Baldessari donate his graphics to skateboards. He believed in Surrealist André Breton’s notion of automatism, but finally chose his own self-created technique of reaching the unconscious known as “paranoiac-critical,” a condition in which one might imitate hallucination while remaining sane.

This method, which the artist ironically described as “irrational knowledge,” was taken by his peers, mostly Surrealists, to a range of disciplines ranging from cinema to literature to fashion. Much of Salvador Dalí’s artwork is rooted in the great tradition of art, and the artist has always freely recognized his obligation to painters like Johannes Vermeer, Raphael, Rembrandt, and Diego Velazquez.

His method is classic. His surface style is reminiscent of van Eyck’s Flemish paintings and the works of the Dutch minor painters of the 17th century. He has created a still life in the style of his renowned compatriot, Zurbaran. His drawings frequently have Renaissance characteristics. His surreal compositions have been compared to those of Hieronymus Bosch, and he has incorporated mythical and religious subjects that are centuries old.

“Hidden shapes” appear frequently throughout painting history. There is no doubt that he is one of the most well-known and well-liked painters of the 20th century; nonetheless, there is a lot of controversy around him and his work.

Many detractors of the artist argue that after his brief period as a surrealist, he made very little, if any, works that contributed to the art world and to his overall career. Many, on the other hand, like and respect his works and aspirations. In fact, more than one museum, such as the Salvador Dalí Museum dedicated to the artist has opened, displaying many of the works that he gave to the art world throughout his lifetime.

Despite engaging in a meaningful engagement with the history of international art throughout his life – ranging from Renaissance artists such as da Vinci to Cubist Pablo Picasso and Max Ernst – Dalí’s dreams remained bravely in this region. Much that appears essential to us today may lose its relevance in the future when Salvador Dalí’s paintings are placed in appropriate context alongside the work of artists from all times.

He will always be remembered as one of the few 20th century artists who mix deep regard for the past with very current sensibilities. People will always be drawn to his work because of his incredibly personal and constantly unexpected imagination, which is the source of his brilliance.

Salvador Dalí’s Artworks

Although paintings were the bulk of Salvador Dali’s artwork, he also made sculptures, jewelry designs, illustrations for numerous publications and book series, and a sequence of pieces for several theaters and performances that were presented in theaters.

His life and work had a significant impact on contemporary art, other artists within the Surrealism movement, and modern artists.

- Great Masturbator (1929)

- The Persistence of Memory (1931)

- The Enigma of William Tell (1933)

- Lobster Telephone (1936)

- Crucifixion (1954)

Recommended Reading

What did you think of our Salvador Dalí Biography? There is so much to cover, maybe we missed something. Luckily there are in-depth books available that will help you understand Salvador Dalí’s paintings and life even better. Here is a list of books all related to Salvador Dalí’s art and lifetime.

The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1993) by Salvador Dalí

He was one of the most vibrant and divisive individuals in 20th-century art. He was a Surrealist trailblazer who was both lauded and loathed for the subconscious images he transmitted into his canvases, which he referred to as “hand-painted dreamed images.” This initial autobiography, which spans his 20s and 30s, is as surprising and enigmatic as his work. It is lavishly adorned with more than 80 images of the artist and his creations, as well as hundreds of his works. Here are interesting glimpses of the talented, ambitious, and ruthlessly self-promoter artist who constructed theater sets, store interiors, and jewelry as easily as he created surrealistic paintings.

- Must-read for anyone interested in 20th century art and its artists

- Superbly illustrated with over 80 photographs of Dalí and his works

- Includes scores of Dalí drawings and sketches

Diary Of A Genius (2020) by Salvador Dalí

This book is considered a foundational text of Surrealism, showing the most amazing and personal machinations of his mind, the unconventional polymath prodigy who has become the true personification of the 20th century’s most highly subversive, frightening, and powerful art movement. This is the mind that can imagine and produce scenes of tranquil Raphaelesque beauty one moment and nightmare scenes of soft watches, flaming giraffes, and fly-covered corpses the next. This book is required reading for anybody interested in 20th-century art and one of its most brilliant and captivating individuals.

- Includes a brilliant and revelatory essay on Salvador Dalí

- Illustrated throughout with over 60 works by the artist

- One of the seminal texts of Surrealism

Salvador Dalí made his debut in the art world in 1929 and remained in the public light until his passing almost 60 years later. His most significant conceptual addition to Surrealism was his early 1930s formulation of a process to organize confusion and thus promote a thorough undermining of reality. The approach described a purposefully bewildered state of mind that allowed a person to link seemingly unconnected events, opening up new pathways of thinking and production. A few well-known Salvador Dalí quotes include: “Don’t bother trying to be contemporary. Regrettably, it is the one thing that you cannot escape no matter what”, and “I adore educated foes as much as I despise ignorant ones who promote me.”

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Salvador Dalí Die?

He died from a heart attack. He was busy listening to Tristan and Isolde, his most favored record, when he passed. He passed on the 23rd of January in 1989.

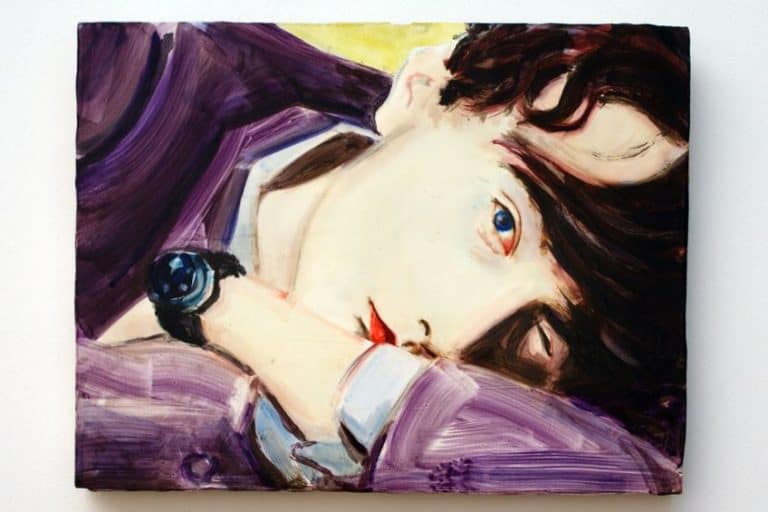

Is There a Salvador Dalí Self-Portrait?

There are in fact several Salvador Dalí self-portraits. He was famed for being arrogant and self-centered, yet this would emerge to be crucial to his success. His self-portraits teach us more about how he saw himself, and he had a complicated relationship with himself. He worked in a lot of different art forms outside surrealism, and as a result, we have been given his picture in a variety of ways, including the cubist item on this page. He also worked in impressionism when he was younger, although certainly not in portraiture.

What Was Salvador Dalí Known For?

Dalí was interested in the art style known as surrealism. This was an art style in which painters created dream-like images and depicted circumstances that would be strange or inconceivable to encounter in everyday life. Salvador Dalí created sculptures, paintings, and films based on his visions. He created melted clocks and floating eyeballs, as well as clouds that resemble facial features and rocks that resemble bodies.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Salvador Dalí – The Archetypal Surrealist.” Art in Context. April 6, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/salvador-dali/

Meyer, I. (2022, 6 April). Salvador Dalí – The Archetypal Surrealist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/salvador-dali/

Meyer, Isabella. “Salvador Dalí – The Archetypal Surrealist.” Art in Context, April 6, 2022. https://artincontext.org/salvador-dali/.