Camille Claudel – Her Life and Art in Rodin’s Shadow

Behind every great man, there is a great woman. Camille Claudel was the great woman behind the famous Auguste Rodin: the founder of modern sculpture. For many years Camille Claudel’s biography was shadowed by that of Auguste Rodin and she was mostly known as his muse and mistress. This article, however, explores the life and work of Camille Claudel as a remarkable artist and sculptor in her own right.

Artist in Context: Who Was Camille Claudel?

| Date of Birth | 8 December 1864 |

| Date of Death | 19 October 1943 |

| Country of Birth | France |

| Art Movements | Impressionism |

| Mediums Used | Bronze and Marble |

Camille Claudel’s full name was Camille-Rosalie Claudel and she was born in 1864 in Villeneuve-sur-Fère, France. Camille Claudel’s biography mostly describes her as the assistant, mistress, and muse of the French sculptor, Auguste Rodin, or as the sister of the French poet, Paul Claudel. However, she was so much more than that. Claudel was also a sculptor who was greatly inspired by Greco-Roman mythology and by the works of Donatello and Cellini.

Despite the gender restrictions and prejudices imposed on her by 19th century society, Claudel succeeded in becoming an artist against all odds. This article takes a closer look into the journey of Camille Claudel.

Camile Claudel’s Biography: Childhood and Early Education

Camille Claudel was the first child born to a family of Catholic farmers with high social standing. Claudel’s brother, Paul Claudel, was born when she was four years old. Together they grew up in many different places, including Villeneuve-sur-Fère, which Claudel loved the most. She enjoyed the natural landscape of the countryside and it inspired her to start working with clay at the age of 12.

Her early works were admired by Alfred Boucher, who advised her parents to invest in her skills.

In 1881 Claudel moved to Paris where she was enrolled in the Colarossi Academy, which is now called the Grande Chaumière. To be admitted into the Colarossi was a marvelous achievement, as very few art institutions accepted female students. Claudel’s acceptance into art school gave her the confidence to rent a studio space in 1882 alongside three fellow female sculptors, including Jessie Lipscomb, Amy Page, and Emily Fawcett.

Alfred Boucher, who recognized her talents as a child, became her mentor and advisor. Their relationship was always a professional one, but Boucher’s respect and adoration towards Claudel can clearly be seen in the sculpture he made of her in 1882, titled Camille Claudel lisant.

Whilst women were typically portrayed as sensual and erotic in sculptures during this period, Boucher instead portrays Claudel in a contemplative gaze, sitting down fully clothed with a book in her hand.

Assistant, Muse, and Mistress

Boucher, unfortunately, had to leave Claudel when he won the Grand Prix du Salon and moved to Italy. Boucher appointed Auguste Rodin to take his place as an advisor to the young group of female students. Rodin, at age 43, was already an acclaimed sculptor at the time and Claudel quickly became one of his best students.

This relationship soon developed into more and Claudel became the lover and muse of Rodin. Claudel started working as an assistant in Rodin’s studio in 1883.

The relationship between the two sculptors was a cause of concern for Claudel’s family and whilst her father still supported her financially, the rest of her family treated her as an outcast and she was forced to leave her family home. Claudel became one of Rodin’s most trusted assistants and she worked on some of Rodin’s most famous sculptures, including The Kiss (1882) and The Gates of Hell (1880-1890). Rodin openly praised the work of Claudel and described her as an original creative genius.

Rodin admired Claudel not only for her art but also for her beauty, and both sculptors modeled several portraits of one another. Rodin’s intense feelings for Claudel can be seen in his works like “Eternal Springtime” (1884), “I Am Beautiful” (1885), “Portrait of Camille Claudel with a Bonnet” (1886), and “Mask of Camille Caudel” (circa 1895).

Whilst their romantic relationship also developed, Rodin was already in a serious relationship with Rose Beuret and he had refused to end his relationship with Beuret. Claudel’s jealousy towards the relationship between Rodin and Beuret troubled her greatly and soon developed into paranoia and rage.

The Sculptor

During the time spent as an assistant to Rodin, Claudel continuously worked on developing her artistic skills. She even became a big inspiration for Rodin’s art style. In 1886, Camille Claudel won a prestigious Salon Prize for her sculpture called Sakuntala. Critics praised the work’s sensitivity and psychological influence on the human figure.

Camille Claudel’s work started to change when her relationship with Rodin finally ended in 1892, nearly ten years after their affair had begun.

After the separation, Claudel no longer had access to the equipment she could use in Rodin’s studio and her new works were smaller and showed emotions of sorrow and despair. Whilst Rodin offered to support Claudel financially, the betrayal she felt had resulted in her refusal to accept any help from Rodin.

Despite her sadness and loss of support, she continued to create and did some of her best work after the relationship had ended. Claudel’s new work drew from everyday experiences and was inspired by Art Nouveau and Japanese prints.

Claudel also started experimenting with different materials and her work became even more unique.

Late Period

Since 1899, Claudel had lived and worked alone in her studio and she started to have serious financial difficulties. Records show that Rodin had searched for commissions for Claudel and that he paid her rent in 1904. By 1905, however, Claudel’s mental health started deteriorating and she became more reclusive. In 1912, Claudel destroyed most of her work in her studio out of frustration and rage. In 1913, Claudel’s father, who had always supported her choices, had passed away.

Claudel’s family took the opportunity to have Claudel diagnosed with paranoia and schizophrenia and she had been admitted to an asylum. After her admission, the remainder of her studio had been destroyed.

The tragic part is that Claudel’s doctors had urged her family that it was not necessary to admit Claudel as she was not insane, but the family, who disagreed with Claudel’s life choices, had wanted her admitted indefinitely. Claudel had sadly spent 30 years in the asylum and had only had very few visits, including from her old artist friend, Jessie Lipscomb, and her brother, Paul Claudel.

Rodin attempted to help Claudel, but he was unsuccessful, and her admirers and patrons had openly criticized her family’s unfair decision. Camille Claudel had died alone at the age of 78, in 1943. Her family never claimed her body and she was buried in the mass grave of the asylum.

Important Camille Claudel Sculptures

Camille Claudel created many works during her career. Unfortunately, not all of them stood the test of time. Today, only 90 Camille Claudel sculptures remain. Many of Camille Claudel’s works were destroyed by her own hand out of rage and despair. The following section discusses some of Camille Claudel’s most important remaining works.

Sakuntula (Vertumnus and Pomona) (1886 – 1905)

| Date | 1886 – 1905 |

| Medium | White marble on a red marble base |

| Size | 91 cm x 80.6 cm x 41.8 cm |

| Collection | Musée Rodin |

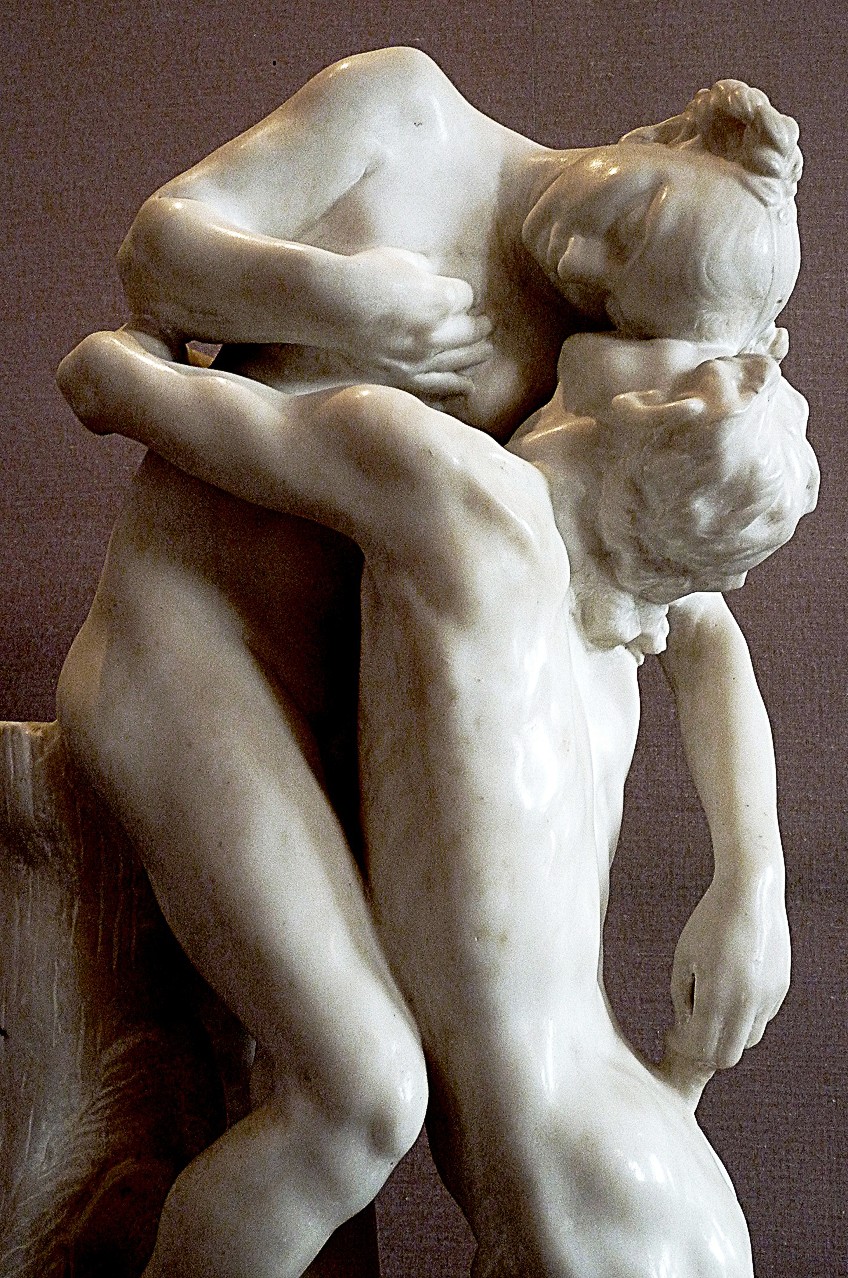

Sakuntula is one of Claudel’s earlier works that shows clearly her classical sculpture influence, yet it is a vastly unique work, different from those created by male artists at the time. What made Claudel’s work so unique is that the two figures are not only depicted in a way that shows their physical form, lust, and desire, but also the attraction between them driven by the power of the mind.

The relationship between the two lovers is depicted in a way that tells us they are equal partners and one is not shown with more power than the other.

The original title of the work, Sakuntula, is derived from an Indian legend written by Kalidasa, a poet. The legend tells the story where a wife is reconnected to her husband after a magic spell had kept them apart. The work was originally modeled in 1886, but the marble version was only commissioned in 1905 and by then the sculpture was renamed Vertumnus and Pomona. This new name is derived from the tale where a Roman god disguised himself as an old woman. He did this to win the trust of the goddess of fruit.

This renaming might be indicative of the relationship between Claudel and Rodin, which developed from one of pure love to distrust and betrayal.

The Waltz (1889 – 1905)

| Date | 1889 – 1905 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Size | 114 cm (height) |

| Collection | Musée Camille Claudel |

This bronze sculpture was created in the same year that her relationship with Rodin began. The sculpture shows a couple during a dance. The work illustrates the sensual nature between the two dancers who are holding each other in a passionate embrace.

The work is romantic and full of movement and happiness.

There seems, however, to be a moment of transformation in the work. Whilst the body of the male dancer is completely whole, the female dancer is only half of herself, her legs transformed into cloth. This transformation of the female body might be an early sign of Claudel’s feeling of uncertainty in her relationship with Rodin, perhaps illustrating ways in which she felt unseen.

The Gossips (1897)

| Date | 1897 |

| Medium | Onyx Marble and Bronze |

| Size | 45cm x 42.2 cm x 39 cm |

| Collection | Musée Rodin |

The Gossips is a sculpture that illustrates four women sitting in a circle, having a seemingly secret conversation among themselves. Adding to the feeling of secretiveness in the work are the two walls that, as part of the sculpture, situate the women in a corner space created by the encroaching walls.

There is a sense of paranoia that comes through in the work, which might be an indication of Claudel struggling with her mental health. In a letter to her brother, she writes that the work was inspired by a group of women on a train that she observed talking closely to each other.

By the time Claudel created this work, her relationship with Rodin had been severed for some time and as an artist, she sought to find her unique style, independent from Rodin’s influence on her. In her new works, Claudel focussed on the intimacies she observed in the mundane everyday life environments around her. Her work became more feminine and she experimented with different materials.

This made Claudel’s new work pioneering in that it didn’t focus on myth, but rather on personal reflection, a notion that would later dominate the 20th century art scene.

The Wave (1897 – 1903)

| Date | 1897 – 1903 |

| Medium | Onyx Marble and Bronze |

| Size | 62 cm x 56 cm x 50 cm |

| Collection | Musée Rodin |

The Wave is a work that is full of happiness, but also one of impending danger. The work illustrates three women dancing in the nude in a circle on a giant wave. The woman’s unruly hair reminds one of the volitions of nature. The women are portrayed as completely being as free as the sea itself as they are immersed in the present moment of their dance.

The wave is, however, a threat to their dance and there is sadness looming in the inevitability of their demise, as the sea is designed to consume them.

The work is seen to be influenced by Japanese art and more directly by Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave (1832), which was exhibited in Paris at the time. The work is arguably also influenced by Claudel’s mental state. The Wave is often described as being an indication of Claudel having feelings of impending doom in her life as an artist.

The work can also be seen as nostalgic, portraying the earlier days in Claudel’s career when she shared a studio with fellow young female artists, who also became her friends.

The Age of Maturity (1899)

| Date | 1899 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Size | 121 cm x 181.2 cm x 73cm |

| Collection | Musée Rodin |

The Age of Maturity (1899) is arguably Claudel’s most well-known sculpture. The sculpture illustrates a woman that begs her partner not to leave her. The male figure has an outstretched hand toward his female lover, but he faces away from her and does not look back to see her face. The male lover has a deliberate movement that is pulling away from the woman kneeling behind him, desperate for his presence.

This sculpture is a clear illustration of Claudel’s feelings towards Rodin and their tumultuous relationship.

The work was originally presented to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1899 to be considered for a bronze casting. Rodin, however, was on the panel that decided that the cast was not to be commissioned. Rodin was apparently offended by the work and Claudel was suspicious that he had sabotaged the panel’s decision.

In 1902, Captain Tisser had finally commissioned a bronze cast of the work.

Reading Recommendations

Camille Claudel has for most of her life been overshadowed by the famous Rodin. For many years after her death, she was still mostly discussed simply as the lover and assistant of Rodin. It is only in recent years that new interest has been cast on the life and work of Claudel. Many new documentaries and books have since been released to explore the life of the mysterious artist and her tragic life. Below are three recommendations of books to start with when exploring the life of Claudel in more depth.

Camille Claudel (1992) by Anne Delbee

This book is a fictionalized biography of the artist Camille Claudel. To map the story of the artist’s life, the author uses photographs of the artists’ works and letters written by the artist during her years in the asylum. The book is written with sensitivity and sympathy for the artist, providing an insightful understanding of the story of Claudel’s life as an artist and a woman.

- Fictionalized biography of the artist

- Restores Claudel to her rightful place as a woman and artist

- Illustrated by photographs of the artist's work and her letters

Mind of Steel and Clay: Camile Claudel (2017) by Enrique Laso

This book uncovers the dark years of Camille Claudel’s life in the confinement of the asylum. The includes many accounts of Claudel’s time in the asylum, provided through the diary of the Medical Director of the psychiatric hospital in which Claudel spent many of her years. The book explores the mysterious years of Claudel’s confinement in great depth and illustrates her hardships as she grabbled with hope, passion, art, guilt, madness, and genius.

- Written by the director of Claudel's psychiatric hospital

- Explores the unknown years of Claudel's confinement

- Tells the tragic tale of an extraordinary woman and artist

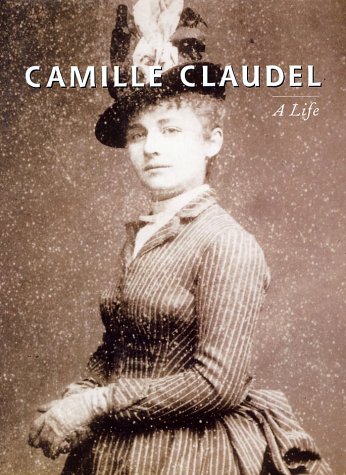

Camille Claudel: A Life (2002) by Odile Ayral-CLause

This book is another carefully researched biography of Claudel’s life as a sculptor and woman. The book draws from an array of family photographs, private letters, and medical records. The book also takes a closer look into the nature of the relationship between Claudel and Rodin.

- A carefully researched portrait of the life of sculptor Claudel

- An examination of her works drawn from unpublished materials

- Discusses her relationship with Rodin and the challenges as a woman

Camille Claudel is an artist that was for most of history overshadowed by Rodin. She was mostly considered as the assistant, muse, and mistress of Rodin, and not as a successful artist in her own right. It is only in recent years that the genius of Camille Claudel’s sculptures has been recognized. Claudel made works that were highly original and ahead of their time, as they were not only following Classical traditions of sculpture but rather investigated in a more subjective manner the human condition. While antisocial and eccentric behavior by male artists had been tolerated by societies throughout history, the same could not be said for the few practicing female artists at the time. Instead, Claudel’s struggle with mental health had marked her as an outcast and she was locked away in an asylum. The Camille Claudel Museum that opened in 2017 in France not only celebrates the uniqueness of Claudel’s work but also highlights her struggles for success in a patriarchal system.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Can Camille Claudel’s Works Be Seen?

Many of Camille Claudel’s works can be seen at the Musée Rodin in Paris, France. The Musée Camille Claudel, which opened in 2017 in France, gives Claudel the type of recognition as an artist that she always strived for in her life. The museum displays nearly half of all of Claudel’s existing work. The museum is about 100 km out of Paris and is built in Claudel’s most loved childhood town, Norgent-sur-Seine.

What Inspired Camille Claudel’s Sculptures?

Camille Claudel was inspired by Greco-Roman literature and mythology. She drew inspiration from classical art, including that of Donatello and Cellini. Apart from this, Claudel was also influenced by her daily environment and varying mental states, something which made her very unique as an artist in France at the time.

How Many Sculptures Did Camille Claudel Make?

Of all the works that Camille Claudel made, only 90 of them still exist today. Claudel destroyed many of her own works, and some are believed to be lost. The majority of Camille Claudel sculptures that can be seen today are small delicate works, which stand in stark contrast to Rodin’s large and dominating works. Unlike Rodin, Claudel never received a public commission and many of her plaster models were never cast into bronze. A few of her plaster models were, however, cast in bronze years after their creation by Eugène Blot, Claudel’s art dealer in Paris.

Chrisél Attewell (b. 1994) is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. Her work is research-driven and experimental. Inspired by current socio-ecological concerns, Attewell’s work explores the nuances in people’s connection to the Earth, to other species, and to each other. She works with various mediums, including installation, sculpture, photography, and painting, and prefers natural materials, such as hemp canvas, oil paint, glass, clay, and stone.

She received her BAFA (Fine Arts, Cum Laude) from the University of Pretoria in 2016 and is currently pursuing her MA in Visual Arts at the University of Johannesburg. Her work has been represented locally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, residencies, and art fairs. Attewell was selected as a Sasol New Signatures finalist (2016, 2017) and a Top 100 finalist for the ABSA L’Atelier (2018). Attewell was selected as a 2018 recipient of the Young Female Residency Award, founded by Benon Lutaaya.

Her work was showcased at the 2019 and 2022 Contemporary Istanbul with Berman Contemporary and her latest solo exhibition, titled Sociogenesis: Resilience under Fire, curated by Els van Mourik, was exhibited in 2020 at Berman Contemporary in Johannesburg. Attewell also exhibited at the main section of the 2022 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Learn more about Chrisél Attwell and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Chrisél, Attewell, “Camille Claudel – Her Life and Art in Rodin’s Shadow.” Art in Context. April 8, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/camille-claudel/

Attewell, C. (2022, 8 April). Camille Claudel – Her Life and Art in Rodin’s Shadow. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/camille-claudel/

Attewell, Chrisél. “Camille Claudel – Her Life and Art in Rodin’s Shadow.” Art in Context, April 8, 2022. https://artincontext.org/camille-claudel/.