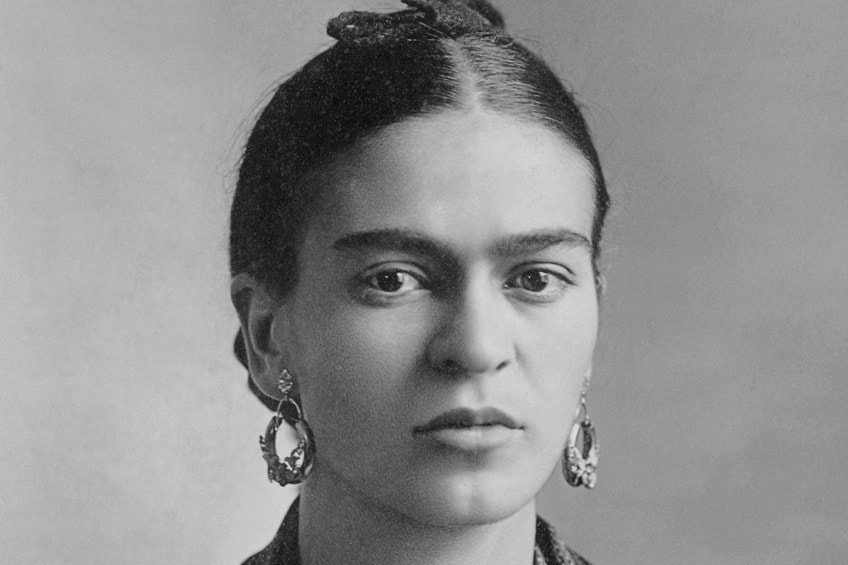

Frida Kahlo – Mother of Mexican Magical Realism

Frida Kahlo’s art frequently utilizes pictorial depiction of bodily suffering in an effort to properly comprehend psychological trauma. One of the most significant Frida Kahlo facts is that prior to her work, the lexicon of bereavement, mortality, and individuality had been fairly successfully explored by certain male creators of art, yet had not been seriously deconstructed by a female artist. In this article, we will be taking an in-depth look into the art and life of this incredible artist and answering questions such as “What is Frida Kahlo known for?” and “How did Frida Kahlo die?”

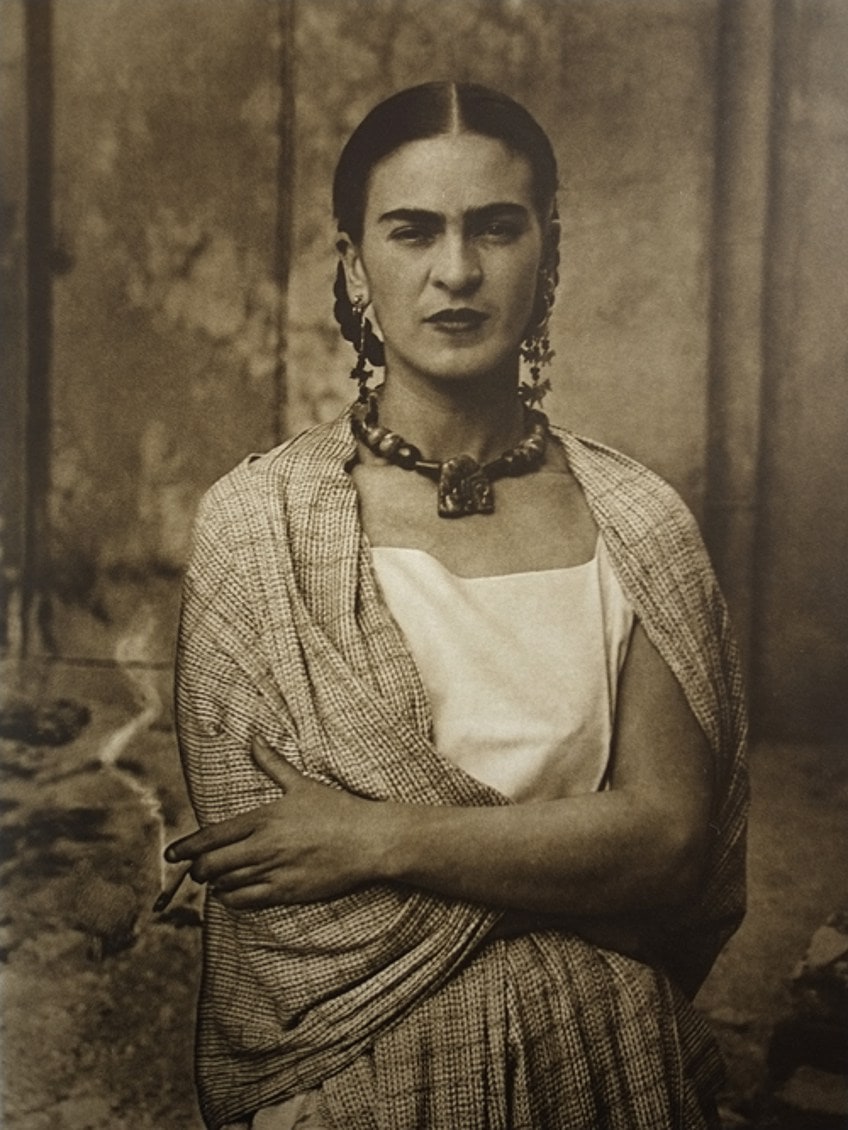

A Frida Kahlo Biography

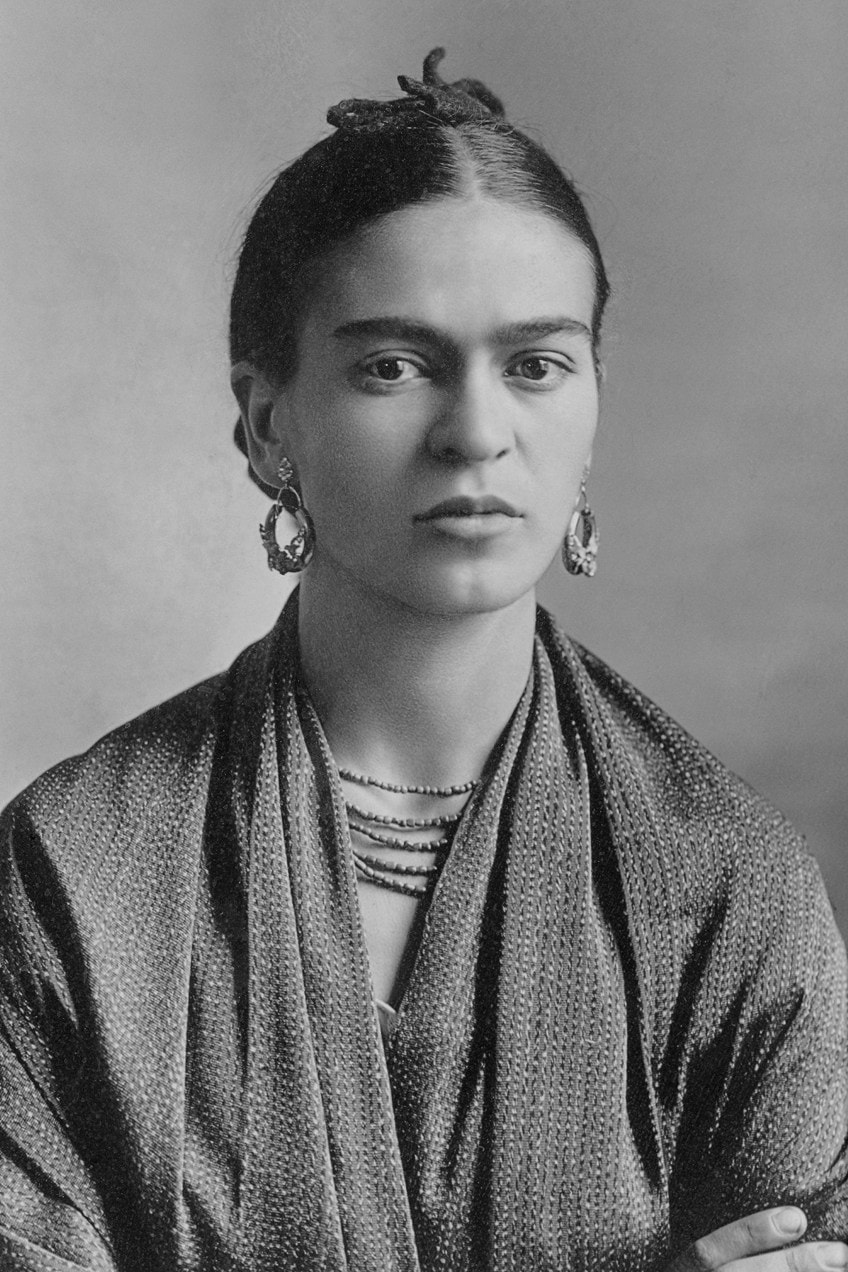

Frida Kahlo’s artwork not only embraced an established vernacular, but she also elaborated on this, making it her own. Kahlo peeled herself open to reveal her inner workings to further illustrate people’s behavior on the surface by actually displaying internal organs and showing her own anatomy in a wounded and damaged condition.

Frida Kahlo’s portraits are iconic and offer lifelong trauma therapy, and her impact cannot be overlooked as not just a “talented painter,” but also a woman deserving of our affection. But before we explore the symbolic subtleties of her work, let us explore her life and career by answering questions such as “When was Frida Kahlo born?” and “Where was Frida Kahlo born?” You can find all important information about her in our article “Frida Kahlo Facts“. Her famous quotes can be found in our article “Frida Kahlo Quotes“.

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Date of Birth | 6 July 1907 |

| Date of Death | 13 July 1954 |

| Place of Birth | Coyoacan, Mexico |

Childhood

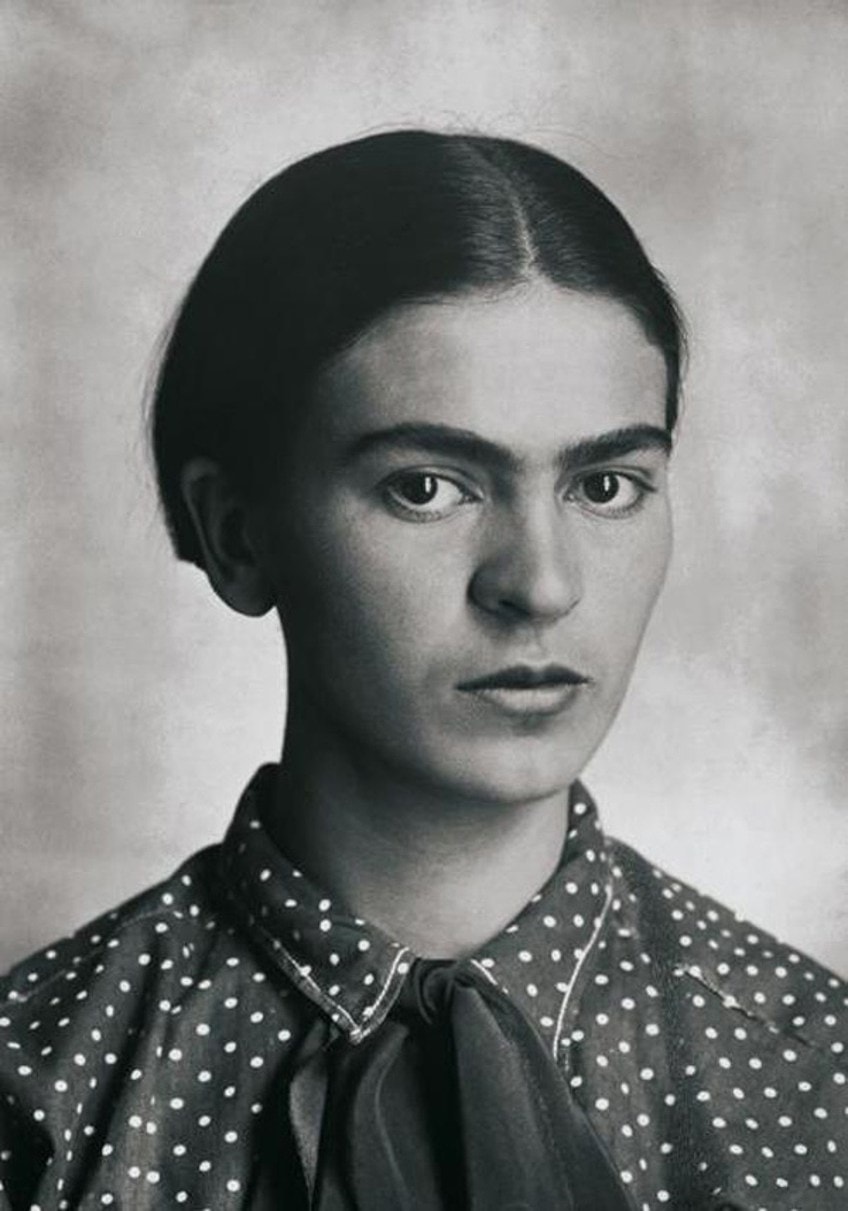

Frida Kahlo was born in Coyoacan, a small village situated on the fringes of Mexico City on the 6th of July 1907. Wilhelm, Kahlo’s father, was originally from Germany and had migrated to Mexico in his youth, where he continued for the remainder of his life, eventually assuming her family’s photographic company. Her mother, on the other hand, was a mix of Mexican and Spanish descent, and she raised her children in a disciplined religious environment.

Besides her family’s conservatism, religious extremism, and inclination to erupt, numerous other incidents in her upbringing had a profound impact on her.

Kahlo developed polio when she was six years of age; a lengthy rehabilitation separated her from other youngsters and irreversibly crippled one of her legs, requiring her to move with a hobble after rehabilitation. All of her siblings attended a convent school, suggesting that Kahlo had a need for broad study, which resulted in her father making distinct selections specifically for her. Wilhelm enrolled the young woman at the German College.

Kahlo was thankful for this, and notwithstanding her rocky ties with her mother, she always ascribed her father with tremendous empathy and intelligence. Nonetheless, she was fascinated by both lines of her ancestors, and her blended Mexican and European origins generated a life-long curiosity in her attitude to both her art and life. At the German School, she had a dreadful encounter where she was physically molested and compelled to quit. Fortunately, the Minister of Education had revised the schooling policies at the time, and females were accepted to the National Prep School commencing from 1922.

She was amongst the first 35 female students enrolled, and she began studying health, horticulture, and sociology. Frida excelled academically, had a strong appreciation for Mexican culture, and then became politically and socially involved.

Early Training

Diego Rivera was creating a mural in her school’s amphitheater when Kahlo was 15 years old. When she saw him painting, Kahlo had an instant of attraction and intrigue that she would go on to pursue later in life. Simultaneously, she helped her father in his photographic shop and took sketching lessons from her father’s colleague, Fernando Fernandez, for whom she worked as an assistant engraver.

At the same time, Kahlo encountered the “Cachuchas,” a rebellious organization of pupils who affirmed the adolescent creator’s defiant nature and fostered her interests in reading and philosophy.

In 1923, Frida Kahlo fell in love with another member of the group, Alejandro Arias, and the two were intimately connected until 1928. Unfortunately, on their ride home in 1925, the two were injured in a near-fatal bus accident. Her body was fractured all over, which included a shattered pelvis, and a bar pierced her womb. She was immobilized and tied in a plaster corset for four weeks in the hospital, and she was immobile at home for many months after that.

During her lengthy rehabilitation, she decided to explore with small-scale autobiographical portraits, leaving her medical studies owing to pragmatic considerations and shifting her concentration to painting.

Throughout her period of recuperation in solitude, Kahlo’s parents set up a customized workstation, provided her with a set of colors, and hung a mirror above her head so that she could observe her own image and create self-portraits. She spent hours contemplating metaphysical concerns created by her experiences, such as alienation from her personality, increased introspection, and an overall feeling of impending death.

She leaned on the intense graphical realism familiar from her father’s photography portraits and tackled her own early photographs with the same emotional sensitivity. Throughout this period, Kahlo strongly contemplated pursuing a career as a medical illustrator because she viewed it as a way to combine her talents in art and science.

In 1927, she was sufficiently strong enough to depart her bedroom, rekindling her friendship with the Cachuchas organization, which had become increasingly political by this time. She entered the Mexican Communist Party and started to become acquainted with Mexico City’s cultural and political communities.

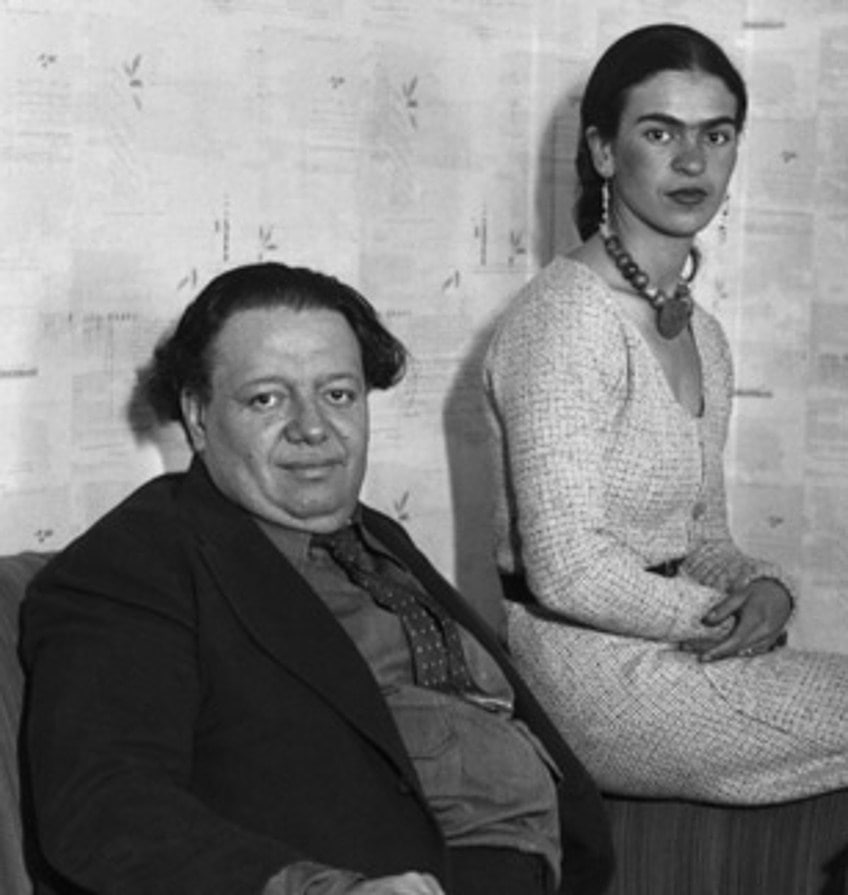

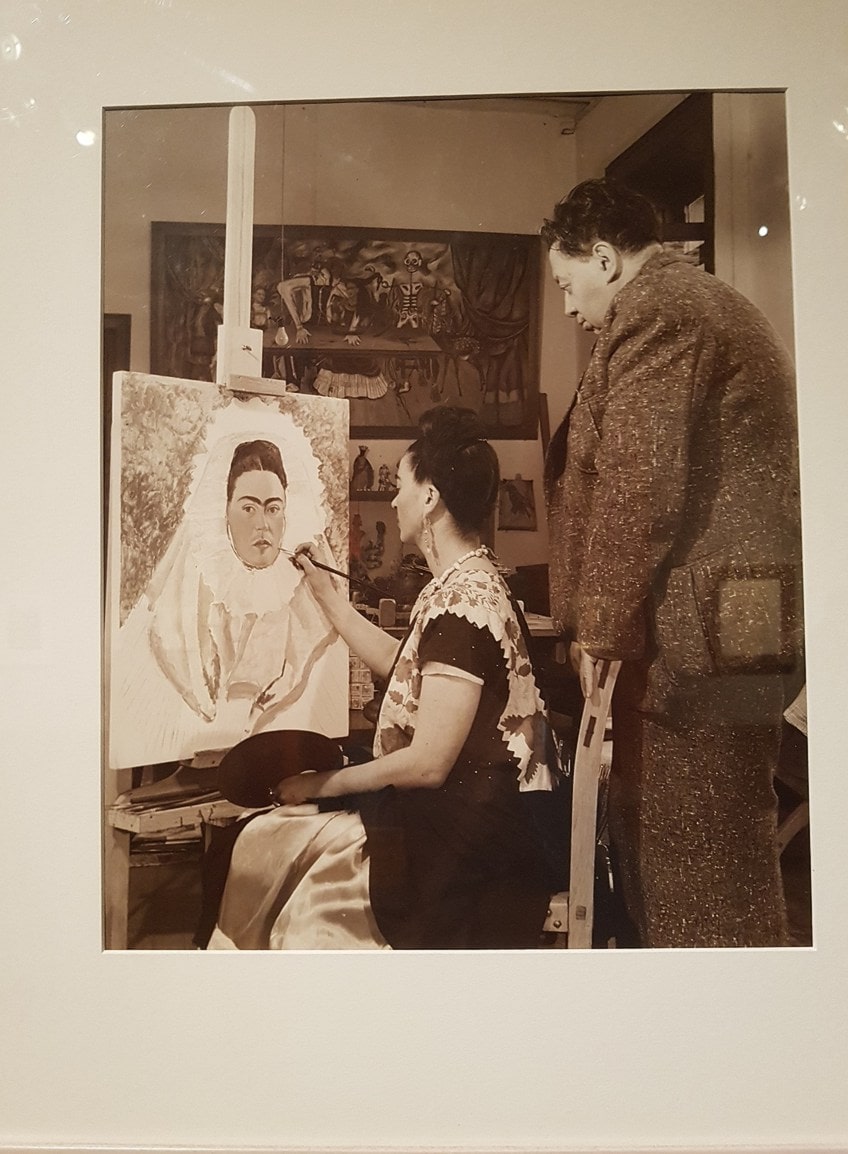

She made good friends with the photographer Tina Modotti and Cuban rebel Julio Antonio Mella. In June 1928, she was formally presented to Diego Rivera during one of Modotti’s frequent parties, who was arguably one of Mexico’s most recognized painters and a highly prominent figure of the PCM.

Shortly after, she openly requested him to judge if her artwork was suitable for maintaining a profession as a painter after examining one of her pictures.

He was blown away by the sincerity and uniqueness of her artwork and convinced her of her abilities. Regardless of the fact that Rivera had been previously married before and was reputed to have an unquenchable affection for ladies, the two rapidly established a passionate connection and were wedded in 1929.

Mature Period

By the beginning of the 1930s, Frida Kahlo’s artwork had grown to encompass a more forceful perception of Mexican nationality, a feature of her art that arose from her connection to Mexico’s contemporary indigenous culture and her desire in protecting Mexicanidad during the advent of fascism in Europe. Her desire to distance herself from her German ancestry is indicated by her title from Frieda to Frida, as well as her desire to adopt the indigenous Tehuana attire from previous matriarchal periods.

Two failed pregnancies at the period increased Kahlo’s paradoxically brutal and beautiful expression of the uniquely feminine situation through metaphor and autobiographical.

During the early 1930s, Kahlo and Rivera resided in San Francisco, Detroit, and New York as Rivera worked on murals. She also accomplished key pieces such as Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States (1932) and Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931), the former conveying her impressions of the competition between environment and commerce in the two regions.

During this period, she met and befriended Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, and Edward Weston. While in San Francisco, she also met Dr. Leo Eloesser, the physician who would become her nearest health consultant through to her eventual death. Shortly after the inauguration of Rivera’s massive and contentious painting for the Rockefeller Center in New York, the pair returned to Mexico because Kahlo was unhappy. They relocated to a new home in San Angel’s affluent area. The home was divided into two sections that were connected by a bridge.

This arrangement was suitable because their marriage was under extreme stress.

Rivera, who had already been adulterous, was having a relationship with Kahlo’s younger sister Cristina at the time, which naturally wounded Kahlo more than her husband’s past indiscretions. At this moment, Kahlo decided to pursue her own adulterous relationships. She met Nickolas Muray, a photographer from Hungary who was on vacation in Mexico, not long after her return from the United States. The two had an on-again, off-again romance that lasted ten years, and Muray is recognized for capturing Kahlo most vibrantly on camera.

While residing in her own apartment away from San Angel after her relationship with her sister, Kahlo also had a brief romance with the artist Isamu Noguchi. Till Kahlo’s passing, the two socially and politically minded painters remained good friends. In 1938, during a trip to Mexico City, André Breton, the father of the Surrealist movement, was fascinated by Frida Kahlo’s art and contacted his art dealer friend, Julien Levy, who promptly asked Kahlo to organize her first solo display at his art gallery.

This time, Kahlo came to the United States without Rivera and made quite a stir when she arrived. Her bright and exotic (but truly traditional) Mexican outfits drew a crowd, and her show was a hit.

One of the famous attendees that attended Kahlo’s launch was Georgia O’Keeffe. Kahlo spent many months partying in New York before sailing to Paris in early 1939 to showcase with the Surrealists. That show was not as popular, and she rapidly became bored with the Surrealists’ over-intellectualism. Kahlo went to New York with the intention of continuing her love interest with Muray, but he ended the affair since he had found someone else. As a result, Kahlo returned to Mexico City, and Rivera demanded a divorce.

Later Years and Death

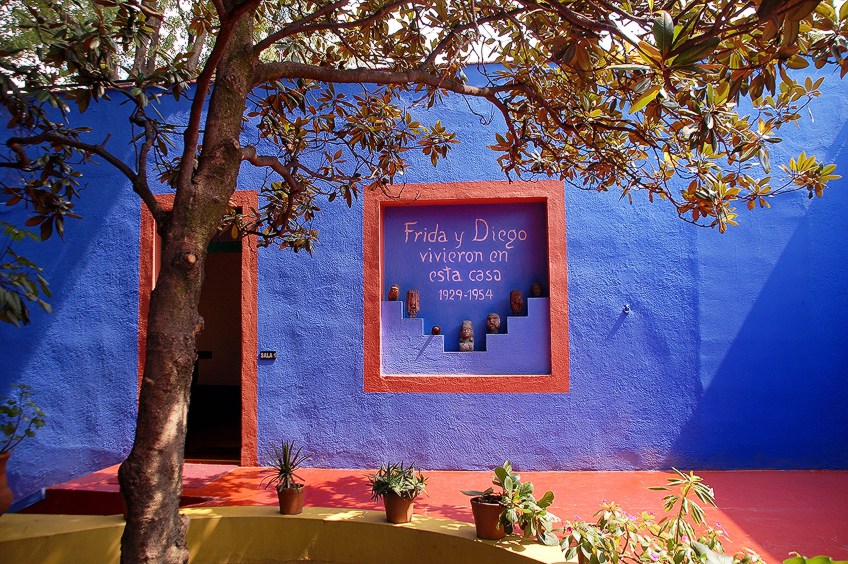

Kahlo returned to La Casa Azul after her separation. She started working on significantly larger canvases after abandoning her smaller works. Kahlo and Rivera wedded in 1940, and their marriage grew less tumultuous as Kahlo’s health declined. Between 1940 and 1956, the ailing artist frequently had to wear supporting back corsets to alleviate her spinal difficulties; she also suffered an infectious skin ailment and syphilis. Her despair and health were aggravated after her father passed away in 1941.

Kahlo was often housebound afterward, and she discovered simple joy in being surrounded by pets and caring for the gardens at La Casa Azul.

She had to make a livelihood from her work, refusing to accommodate clients’ desires if she did not agree with them, but she was rewarded with a national award for her artwork Moses (1945), and The Two Fridas artwork was purchased by the Museo de Arte Moderno in 1947.

Furthermore, the artist became more unwell. She had a difficult procedure to attempt to align her spine, but it flopped, and she was often wheelchair-bound from 1950 onward.

In her later years, she managed to work rather voluminously while still being politically active and condemning nuclear testing by Western governments. Kahlo showed in Mexico for the final time in 1953 at Lola Alvarez Bravo’s gallery, her very first standalone display in the country. She arrived at the occasion in an ambulance, with her four-poster bed trailing behind on the back of a truck. The cot was then put in the middle of the gallery, where she could recline for the length of the exhibition. Kahlo died in La Casa Azul in 1954. While the stated manner of death was a blood clot, suspicions have been raised concerning suicide, whether intentional or unintentional. She was 47 years old at the time.

Legacy

Frida Kahlo’s artwork has been identified with Magic Realism, Primitivism, and Surrealism as an individual who was divorced from any formal aesthetic trend. Frida Kahlo’s artwork has proven immensely significant for feminist research and postcolonial discussions after her death, and she has become a global cultural figure.

For public audiences, the creator’s celebrity status has led to the encapsulation of the artist’s work as indicative of Latin American arts in general, distanced from the nuances of Kahlo’s intensely intimate subject matter.

Kahlo’s legacy cannot be understated or overstated. Not only is it possible that each and every female painter working since the 1950s would cite her as an inspiration, but she inspires more than just artists and art enthusiasts. Her work also helps those who have suffered as a consequence of a tragedy, a miscarriage, or a broken marriage. Kahlo expressed complicated experiences via visuals, making them more bearable and offering viewers hope that people might survive, recuperate, and begin again.

Frida Kahlo’s Art Style and Influences

Assessments of how many artworks Kahlo created throughout her lifetime range from fewer than 150 to approximately 200. Her early works, created in the mid-1920s, are influenced by Renaissance artists and European avant-garde painters such as Amedeo Modigliani.

Toward the close of the decade, Kahlo was intrigued by Mexican folk art for its aspects of “magic, innocence, and obsession with death and violence.”

One of Kahlo’s early supporters was Surrealist painter André Breton, who proclaimed her as a member of the group as a painter who created her style “in absolute ignorance of the ideals that prompted my friends’ and my own activity.” Bertram D. Wolfe agreed, writing that Kahlo’s work was a “kind of ‘nave’ Surrealism, which she constructed for herself.” Although Breton saw her as primarily a female influence in the Surrealist movement, Kahlo pushed postcolonial problems and topics to the front of her Surrealist style.

Breton also regarded Kahlo’s work as “wonderfully located at the junction of the philosophical line and the aesthetic line.” Her art combined reality with surrealistic aspects and frequently showed suffering and death. Although she later appeared in Surrealist shows, she declared that she “abhorred Surrealism,” which she saw as “bourgeois artwork” rather than “genuine art that the masses desire from the artist.”

Some art historians have argued that her work should not be regarded as part of the movement at all.

Kahlo, according to Andrea Kettenmann, was a symbolist who was more interested in depicting her interior feelings. Emma Dexter has suggested that because Kahlo got her combination of imagination and reality mostly from Aztec myth and Mexican tradition rather than Surrealism, her works are more akin to magical realism. It mixed realism and imagination and used flattened viewpoints, finely drawn figures, and vivid colors, akin to Kahlo’s.

Mexicanidad

Kahlo, like many other contemporaneous Mexican painters, was profoundly affected by Mexicanidad, a sentimental nationalistic ideology that arose after the revolution. The Mexicanidad movement purported to be against colonialism’s “attitude of cultural degradation,” and it emphasized indigenous traditions in particular. Prior to the uprising, Mexican folk culture – a blend of indigenous and European components – was derided by the aristocracy, who professed completely European lineage and saw Europe as the model of civilization that Mexico should emulate.

Kahlo’s creative goal was to create for the people of Mexico, and she claimed that she hoped “to be deserving, with my works, of the citizens to which I represent and the beliefs that empower me.”

To reinforce this impression, she chose to hide her art studies from her father and Ferdinand Fernandez, as well as her preparatory school education. Instead, she portrayed herself as a “self-taught and unsophisticated artist.” Muralists controlled the Mexican art landscape when Kahlo started her profession as a painter in the 1920s. They made big public works in the style of Renaissance artists and Russian socialist realists: they frequently represented crowds, and their political statements were simple to understand.

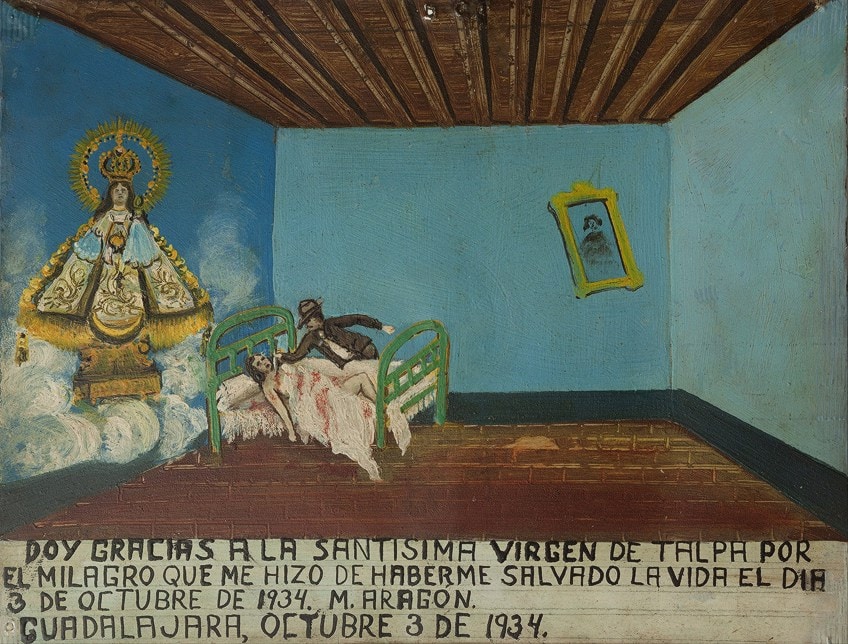

Her aesthetic was mainly influenced by votive canvases, which were postcard-sized religious pictures created by amateur painters, in the 1930s. Their objective was to express gratitude to saints for their safety during a tragedy, and they often showed some occurrence, such as a disease or an accident, from which its client had been protected. The emphasis was on the characters shown, and they rarely included realistic perspective or rich surroundings, reducing the action to its essence.

Kahlo amassed a large collection of retablos, which she placed on the walls of La Casa Azul.

The retablo design, according to Peter Wollen, allowed Kahlo to “explore the limitations of the simply iconic and permitted her to incorporate story and metaphor.” Several of Frida Kahlo’s portraits resemble the traditional bust-length portraits used during the colonial period, but they disrupt the norm by showing their subject as less beautiful than she is in reality. She shifted her focus to this genre more regularly around the close of the 1930s, mirroring shifts in Mexican culture.

Mexicans were rejecting the spirit of socialism for individuality, disenchanted by the aftermath of the revolution and straining to deal with the impacts of the Great Depression. This was echoed in the “personality cults” that sprang up around Mexican cinema actresses like Dolores del Ro.

“Frida Kahlo’s portraits recall the contemporary preoccupation with the close-up of female beauty, and the mystery of feminine specialness represented in film noir,” according to Schaefer.

Kahlo took inspiration from the representation of gods and saints in native and Catholic cultures by continually repeating the same facial characteristics. Among Mexican folk painters, Kahlo was particularly inspired by Hermenegildo Bustos, whose paintings showed Mexican heritage and peasant life, and José Guadalupe Posada, whose works satirized accidents and criminality.

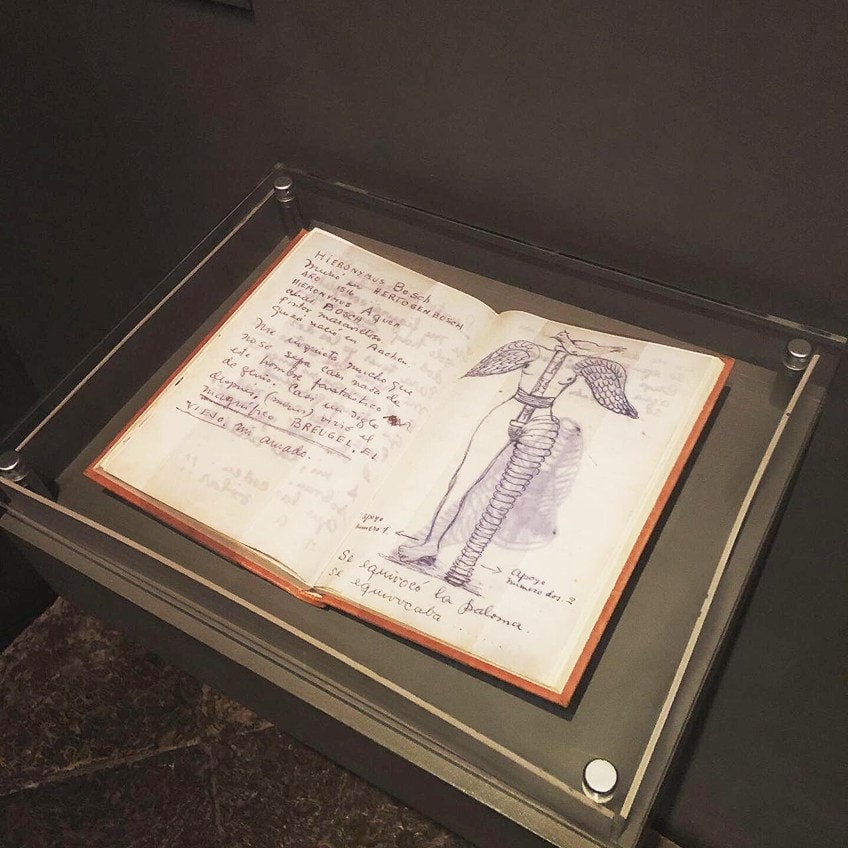

Kahlo was also inspired by the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, whom she referred to as a “man of genius,” and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whose attention on peasant life paralleled her own concern in the Mexican people. Another of her inspirations was the poet Rosario Castellanos, whose poetry frequently chronicled a woman’s situation in patriarchal Mexican culture, a preoccupation with the feminine body, and stories of extreme physical and mental anguish.

Iconography and Symbolism

Frida Kahlo’s artworks frequently include root imagery, with roots sprouting out of her body to connect her to the earth. This highlights the topic of personal progress in a positive sense; being stuck in a certain location, time, and position in a bad sense; and an unclear feeling of how recollections of the past impact the current for good or evil. Kahlo depicted herself as a ten-year-old in My Grandparents and I, carrying a ribbon that expands from an old tree that carries photographs of her grandparents and other forefathers, whilst her left foot is a big tree starting to grow out of the surface.

This mirrored Kahlo’s perception of humanity’s unification with the planet as well as her own sense of solidarity with Mexico.

Trees appear in Kahlo’s works as emblems of optimism, power, and a connection that spans generations. Furthermore, hair appears in Frida Kahlo’s paintings as a sign of development and the feminine, and in Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, Kahlo depicted herself donning a young man’s outfit and sheared off her long hair, which she had just chopped off. She holds the scissors ominously nearby to her genital area, which can be construed as a threatening gesture to Rivera – whose regular infidelity incensed her – or a risk to endanger her own body in the same way she has struck her own hair.

This stood as a sign of how women frequently project their rage for others onto themselves.

Furthermore, the image expresses Kahlo’s dissatisfaction not just with Rivera, but also with Mexican patriarchal ideals, since the scissors represent a malicious idea of masculinity that promises to “rip up” women, both metaphorically and practically. Traditional Spanish norms of macho were largely accepted in Mexico, but Kahlo was always uneasy with machismo. As she endured for the remainder of her life as a result of the bus accident in her childhood, Kahlo expended much of her time in hospitals and having surgery, much of it was conducted by “quacks” who Kahlo felt could return her to her pre-accident state.

Many of Frida Kahlo’s artworks deal with medical imagery, which is expressed in terms of anguish and hurt, with Kahlo hemorrhaging and showing her gaping sores.

Several of Kahlo’s medical paintings, particularly those dealing with delivery and miscarriage, contain a large feeling of guilt, of spending one’s life at the price of someone who has died so that one may live. Although Kahlo included herself and situations from her life in her works, the message was frequently vague.

She didn’t only use them to demonstrate her subjectivity; she also used them to raise problems about Mexican culture and the production of identification within it, including gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic class. Kahlo constructed a sophisticated iconography to address these problems via her work, heavily integrating pre-Columbian and Christian symbolism and folklore in her works.

In most of Frida Kahlo’s portraits, she displays her face as if it were a mask, but it is accompanied by visual signals that allow the spectator to understand deeper meanings.

Aztec mythology is prominent in Kahlo’s works, with motifs such as apes, bones, skeletons, blood, and hearts; these motifs frequently alluded to the stories of Quetzalcoatl, Coatlicue, and Xolotl. Hybridity and duality were two more key concepts that Kahlo took from the Aztec myth.

Many of her works show polar opposites, such as death and life, European and Mexican, and masculine and female. In addition to Aztec traditions, Kahlo regularly featured two important female figures from Mexican mythology in her works of art: La Llorona and La Malinche as interconnected with difficult situations, sorrow, disaster, or condemnation, as being catastrophic, miserable, or “de la chingada.”

For instance, after her miscarriage, she depicted herself as sobbing, with disheveled hair and an unprotected heart, all of which are regarded as part of the look of La Llorona, a lady who killed her children. Originally, the picture was viewed as a simple portrayal of Kahlo’s anguish and pain over her lost pregnancy.

However, interpretations of the symbolism in the artwork and data from Kahlo’s letters about her true thoughts on parenting, the picture have been interpreted as showing the unorthodox and forbidden decision of a woman staying childless in Mexican culture.

Kahlo frequently included her own body in her works, portraying it in various states and conceals, such as injured, shattered, as a kid, or costumed in various clothes, such as a man’s suit, or European clothing. She utilized her body as a symbol to investigate her role in society. Her paintings frequently showed the female body in unusual situations, such as miscarriage, delivery, or cross-dressing. By graphically displaying the female body, Kahlo placed the spectator in the role of voyeur, “making it practically difficult for a viewer not to establish a deliberately held attitude in reaction.”

Recommended Reading

Today discovered a little about life and art and Frida Kahlo. We have tried to go a little deeper than just asking the basic questions such as When was Frida Kahlo born and where was Frida Kahlo born, but there is always more to discover. Perhaps you would like to discover more about her through reading a Frida Kahlo biography and interesting Frida Kahlo facts. Here is a list of selected books on that very subject.

Frida (2017) by Sebastien Paerez

Frida is a magnificent feast of a book that transports the reader into the world of this acclaimed artist, both physically and spiritually. One is lured in by a sequence of sequential die-cut pages, moving through facets of her life, art, and design side while addressing the topics that most inspired her, such as love, death, and pregnancy. Her art has always had the potential to traverse borders and resound with its genuine and realistic representation of the human condition, making it iconic and emotional. There has never been a more fitting tribute.

- A sumptuous feast of a book with a series of die-cut pages

- Allows the reader to enter this revered artist's world

- With excerpts from Frida Kahlo's personal diaries

Frida Kahlo: Her Universe (2021) by Frida Kahlo

Painter Frida Kahlo and her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, are presented in this collection. More than 300 images from the Museo Frida Kahlo’s archives in Mexico City show the audience Kahlo’s unique wardrobe, the remarkable compilations of famous and pre-Hispanic paintings she gathered with Rivera, her correlation with photography, and the background of La casa Azul, her adored blue home which now functions as the gallery’s main house. This book invites us inside Frida Kahlo’s universe, delving into the legacy of a pivotal figure in 20th-century art and culture in her own Mexico and beyond the world.

Through her works, Kahlo transformed herself into the primary character of her own narrative, as a female, a Mexican, and a person in anguish. She understood how to transform each into a metaphor or symbol worthy of conveying humanity’s immense spiritual struggle and beautiful sexuality. The wide array of topics, ideas, thoughts, and emotions developed by two key, iconic icons of contemporary Mexico: She used her physique as a metaphor to analyze her place in society. Her paintings typically depicted the female body in odd circumstances, such as miscarriage, childbirth, or cross-dressing. Kahlo put the spectator in the role of voyeur by graphically showing the female body, “making it nearly impossible for a viewer not to create a purposefully maintained attitude in reaction.”

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Frida Kahlo Die?

In 1954, Kahlo died in La Casa Azul. While the cause of death was declared to be a blood clot, doubts have been raised about suicide, whether deliberate or inadvertent. At the time, she was 47 years old.

What Is Frida Kahlo Known For?

Frida Kahlo reinvented herself via her works as a feminist, a Mexican, and a woman in agony, she is the central figure in her own mythology. She understood how to transform each into a symbol or sign capable of conveying humanity’s immense spiritual resistance as well as its magnificent sexuality. Frida Kahlo’s artwork typically depicts physiological agony pictorially in order to adequately understand psychological trauma.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Frida Kahlo – Mother of Mexican Magical Realism.” Art in Context. March 8, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/frida-kahlo/

Meyer, I. (2022, 8 March). Frida Kahlo – Mother of Mexican Magical Realism. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/frida-kahlo/

Meyer, Isabella. “Frida Kahlo – Mother of Mexican Magical Realism.” Art in Context, March 8, 2022. https://artincontext.org/frida-kahlo/.