H. R. Giger Art – An In-Depth Exploration of Gigeresque Art

Hans Ruedi Giger was a Swiss illustrator most known for his airbrushed depictions of human bodies mingling with technology, an aesthetic dubbed “biomechanical.” His Gigeresque artwork was used in the special effects for the film Alien (1979), which earned an Academy Award for visual design. H. R. Giger’s artwork for the film was influenced by his painting Necronomicon IV (1976).

Table of Contents

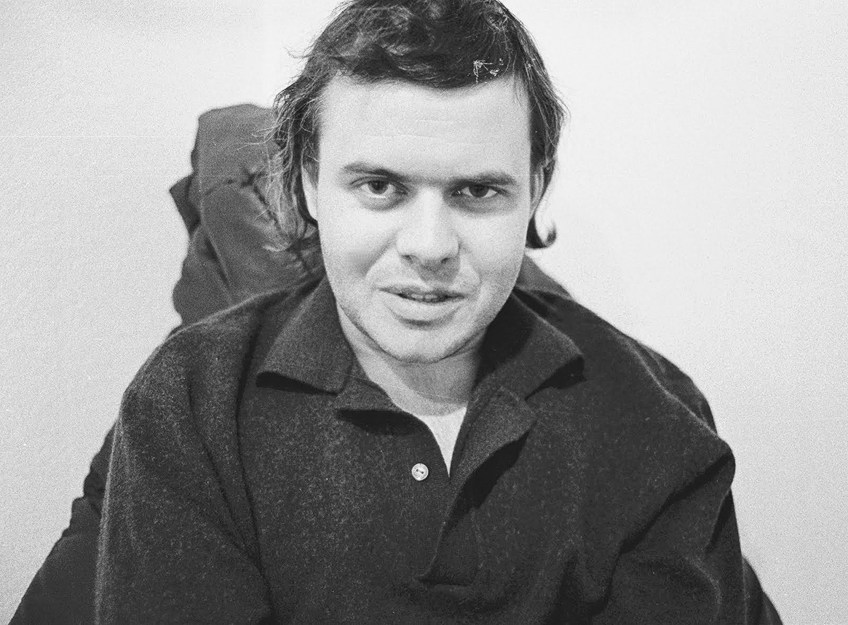

Hans Ruedi Giger’s Biography

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Date of Birth | 5 February 1940 |

| Date of Death | 12 May 2014 |

| Place of Birth | Chur, Switzerland |

H. R. Giger’s artwork has most likely given you nightmares. The Swiss-born artist was renowned for inventing one of the most memorable creatures in film history: the xenomorph, the merciless extraterrestrial race that seeps at the core of the Alien saga.

If you don’t recognize a xenomorph by title, you recognize it by appearance: the black, eggplant-shaped skull; the oozing fangs; the sinuous, spiny body that may look curiously human; and the deadly tail.

The xenomorph is an extraterrestrial from the most desolate parts of space. Hans Ruedi Giger is most recognized for influencing the aesthetic direction of Alien. Even so many years after his passing, his singular outlook continues to influence.

Giger’s oeuvre as an artist, however, transcends beyond the sci-fi brand, blending horror and the macabre and delving into our insatiable curiosity with the things that scare us the most.

Childhood

Giger’s creative approach was shaped by an early obsession with skeletons and mummies, and also by his personal childhood anxieties. He started sketching as a child in Chur, Switzerland, to vent his fear from repeated dreams and weird visions. His fears were heightened by his visit to the Giger family house in Chur. He remembered wide windows leading to dark lanes and the dungeons of that old structure, which had instilled anxiety in him from a young age.

Such concerns were matched by an early curiosity about those objects.

Giger also attributed part of the gloom in his work to his upbringing in Switzerland during WWII, near Nazi Germany. When his parents were worried, he could sense the mood. The bulbs were usually a bluish dark color to keep planes from bombing them. As Giger grew up during the Cold War, the prospect of nuclear war loomed. He replied to it by imagining pictures that altered his fears—not in a pleasant conclusion, but in a way that he could bear artistically.

Education and Career

Notwithstanding his father’s wishes for him to pursue a profession as a chemist, Giger pursued architecture at Zurich’s School of Applied Arts. He began his work as an interior designer after graduation in the mid-1960s but soon opted to explore visual art full-time. He progressed from ink sketches and oil art pieces to utilizing an airbrush to make his art. By the early 1970s, news had spread about Giger’s skill.

He began with displays in galleries, pubs, and communal venues. But he swiftly grew beyond the limitations of the art world.

The painter pioneered the biomechanical art style, which he defined as “biomechanical.” Significantly, his painting appeared on the cover art of Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s Brain Salad Surgery album from 1973, which is universally acknowledged as a progressive rock classic.

Giger even drew the interest of one of the 20th century’s most influential artists: Salvador Dalí. Dalí was exposed to Giger’s art through a mutual acquaintance, Robert Venosa. Dalí was the one who brought Giger’s art to Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, who was looking to cast the renowned Surrealist in his grandiose production of the sci-fi novel Dune (1965). Jodorowsky invited Giger to assist with concept drawings for Dune, but when the project fell through, Giger’s excursion into the realm of the film was put on hold.

Later, in 1977, Giger released the “Necronomicon”, his debut major compilation of drawings, which is now regarded as his second-most important work after “Alien”.

The title sets the tone for pictures that are still astonishing today: peculiar mechanical gnomes nest on lofty lead pillars; bony alien creatures gaze out on mist-covered barren land; and maimed, leathery carcasses are wired up to gangly machines and equipment. The designs are all calibrated between ethereal white tones—the hue of the moon on cement, and black colors that verge on a deep hue of nothingness at points.

Involvement in the Alien Movies

Just after signing on to Alien (1979), director Ridley Scott came upon a print of the Necronomicon on a table in the headquarters of 20th Century Fox. He had never been more certain about anything in his life after taking one glance at it. He was adamant he had to include him in the picture. The xenomorph was inspired by two lithographs in the Necronomicon, which depicted a black, metallic-looking humanoid with the oblong skull that would come to define the creature.

They were quite particular to his idea for the picture, notably in the unusual way they expressed both terror and beauty.

The xenomorph became a pop phenomenon, featuring in eight films, including the main Alien trilogy and spin-offs, as well as computer games, and numerous more pop-culture allusions. By all accounts, Giger’s time working on Alien was favorable, but his newfound celebrity made it difficult for him to decide which projects were worth his time and ability as an artist.

He continued to work in cinema, providing designs for various films, but he frequently generated work for films that were never completed or for ideas that never materialized. So, Giger sought new means to pursue and distribute his work.

Later Career

One manner in which to achieve this was through his Giger Bars, which are located in Gruyere and Chur, Switzerland, and seem like you’re walking into the creator’s universe. The artist inserted his own patterns of spine-like extraterrestrial bones into the masonry of the Gruyere bar, which is part of the rebuilt medieval castle that hosts the H.R. Giger Museum. Giger put his Harkonnen Chairs—black, metal thrones initially scheduled for the lost Dune film in the 1970s—at the booths and countertops.

He didn’t quit making art; he only shifted his focus or the breadth of his work to locations and wider situations. That is one of the final phases of the interior designer making his place in the world of art and subsequently, a more mature artist designing the habitats for his animals. It seems appropriate that Giger’s pursuit of painting was influenced in part by his childhood nightmares since he discovered that his terrors connected with the larger world. He addressed both his personal and societal worries.

What’s appealing is how Giger’s work allows us to confront that darkness—no matter how terrified or hopeless his creations make us feel, we’re lured back for more.

H. R. Giger’s Artwork Style

Giger began with little ink sketches before moving on to oil paintings. He mostly worked with airbrushes for the majority of his career, creating monochrome canvases showing strange, horrific dreamscapes. He also used markers, pastels, and ink in his work.

Giger’s most notable artistic breakthrough was his depiction of human bodies and machinery in chilly, linked interactions, which he termed “biomechanical.” Ernst Fuchs, Dado, and Salvador Dalí were his primary influences.

Painter Robert Venosa introduced him to Dalí. He was inspired by Stanislaw Szukalski, as well as artists Mati Klarwein and Austin Osman Spare. He was also a personal acquaintance of Timothy Leary. From 1962 to 1965, he pursued interior design at Zurich’s School of Commercial Art, and his earliest paintings were created as art therapy.

Other Works

Giger designed furniture, specifically for a cinematic adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel Dune. David Lynch directed the picture many years later, utilizing only Giger’s preliminary sketches. Giger had hoped to collaborate with Lynch, stating in one of his books that Lynch’s picture Eraserhead was closer to achieving his ideal than even Giger’s own works.

Giger’s biomechanical aesthetic was also adapted to interior design. One “Giger Bar” opened in Tokyo, however, the implementation of his ideas disappointed him greatly since the Japanese group behind the initiative did not wait for his design specifications, but instead were using Giger’s crude early sketches. As a result, Giger renounced the Tokyo bar.

The two Giger Bars in his hometown of Gruyères and Chur, Switzerland, were erected under Giger’s careful supervision and exactly represent his original plans.

H. R. Giger’s artwork was leased to decorate the VIP area, the topmost chapel of the landmarked church, at The Limelight in Manhattan, although it was never meant to be a permanent structure and bore little resemblance to the bars in Switzerland. When the Limelight shuttered after two years, the agreement came to an end.

Tattooists and fetishists all around the world have since been affected by Giger’s work.

Ibanez guitars launched an H. R. Giger signature line as part of a license agreement. Giger is frequently mentioned in popular culture, particularly in science fiction and cyberpunk. William Gibson seemed to be particularly enthralled: Yamazaki, a minor character in Virtual Light, regards nanotech Japan’s structures as “Gigeresque art.”

H. R. Giger’s Artworks

Some claim that H. R. Giger’s art is frequently sad and negative, with a focus on death, blood, overpopulation, odd entities, and so on, but he disagrees. His first effective endeavor at reaching out to people through visual art happened in 1969 when a poster of one of his paintings was released.

Giger mentioned Salvador Dalí and Ernst Fuchs as important inspirations for his body and machinery stylizations.

Friedrich Kuhn (1973)

| Date Completed | 1973 |

| Medium | Collotype Print |

| Dimensions | 60 cm x 80 cm |

| Location | Giguere Museum |

The original shot of Friedrich Kuhn’s workshop shows a bizarre sitting man and a palm tree model. The sitting person in Friedrich Kuhn I has been deleted and maybe redone to the left side as a figure with an animal loosely resembling a deer, and the tree shape has become bio-mechanized. A mask put on a rectangle has become a man’s face with broad circular glasses to the right behind the chair.

The easel in the background has taken on the role of a crucifix.

In the painting, Giger transformed the human-looking figure sitting down in the backdrops into the bio-mechanoid cyborg outfit he designed for the film Swiss Made 2069 (1968), in which he further expands the appearance of the suit armor to become even more like one of his highly stylized biomechanoid pictures, clutching a phallic pole in its visible hand.

Giger depicted a sphinxlike feminine bio-mechanoid with an extended transparent cranium and a pipe actually running along the side of it behind the sofa on the left, and this picture would later seem to be evolved into the bio-mechanoid traveler in the painting Necronom V (1970s), which is one of the sets of artworks that motivated the final version of the alien. The female in Friedrich Kuhn has eyes and a skeleton face with a space where the snout would be, but in Necronom V, the eyes and head are hidden by the dome to make her appear blind.

The face behind the couch to the right now transforms into the face of a lovely bio-mechanoid female, complete with the entire figure.

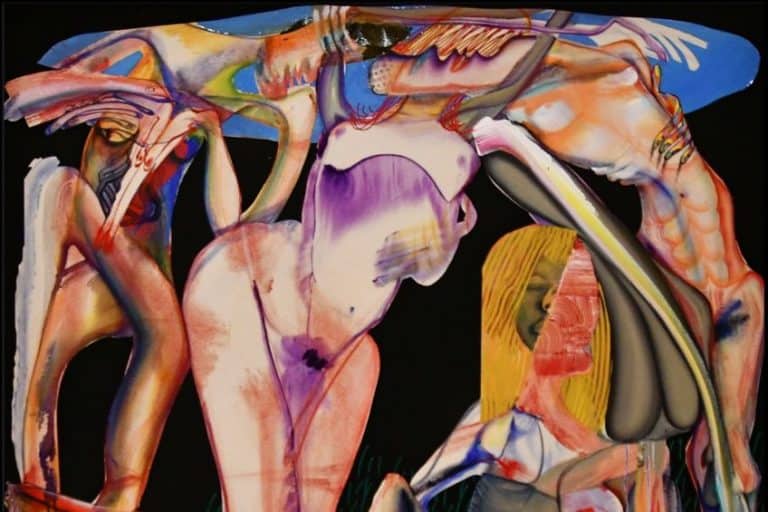

Necronom IV (1976)

| Date Completed | 1976 |

| Medium | Acrylic |

| Dimensions | 100 cm x 150 cm |

| Location | Giguere Museum |

Giger was hired by director Ridley Scott to design the Alien creature. So, the artist traveled to Shepperton Film Studios in London to hand-create his concepts for the Alien universe. Giger’s Necronomicon painting Necronom IV (1976), one of the artist’s most important works, had quickly encouraged Scott to have him involved in designing the extraterrestrial monster.

It displays the upper torso of a creature with only vaguely humanoid characteristics in profile.

It has a very long skull, and its face is nearly entirely made up of bared fangs and enormous insect-like eyes. Hoses emerge from its neck, and tubular extensions and reptile tails dominate its back. The male sexual organ is curled upwards over the skull and is greatly elongated. It expands into a clear bulge, revealing a skeletonized person, as a small saint in a glass coffin. The entire body looks to be in a state of tension that is easily sustained.

Only the strong arms remain near to the human shape, albeit cables and mechanical tracks can be seen beneath their translucent skin, and their substance is more akin to medieval woodcarving grain than tissue. The location of the hands in the image’s top right corner is particularly noteworthy: they appear to be inspired by medieval altarpiece imagery.

The creature’s harsh demeanor contrasts dramatically with the exquisitely thin fingers.

The hands appear to be attempting to take something out of sight as if practicing a grasp or magically manipulating something far away. The figure, of course, fills up the whole picture plane, leaving just a small window into the organic background, which is characterized by slimy shapes and lacks spatial depth. Even though there is no clue of where the creature could be in space and time, it is clear that it cannot be from our planet. The artist had to undergo a complicated transition in order to make this painted creature into a monster for a film.

Ridley Scott was so taken with the original picture that he commissioned H. R. Giger to create a whole “natural history”, which culminated in the film’s final monster.

The monster’s latent dangerousness, which was already visible in the painting, transforms into a kind of practical lethality in the video, which manifests through dynamic motion. Between these two stages was Giger’s creative and artistic process of creating and constructing the requisite figures, which he accomplished almost entirely on his own. The Necronomicon and—with an even larger sense of dread—the Alien are the products of this process, which leaves us with a mix of intrigue and loathing. Alien introduced a lethal life form from space that had never been seen before, and Giger’s creature marked a turning moment in science fiction and horror films.

Giger’s work has left so many traces in so many diverse areas—painting and film, record covers and tattoo culture, as well as science fiction and fantasy genres—that it’s like a “Rosetta Stone,” mixing numerous “languages” that are constantly being decoded. Giger’s work today looks to be a code that has yet to be cracked. In terms of art history, we have an artist whose work was very independent and ultimately impossible to identify, while being inspired by Surrealism and Symbolism. Prior to Alien, he had already produced a significant contribution to 20th-century bizarre art.

His biomechanical concepts continue to be explored separately in fields like media art and bio-art, less as an aesthetic impact and more as ideas inspiring a conceptual approach.

Then there’s the interpretation of Giger’s work that focuses on mythology and psychology, investigating the role of individual and collective phobias in his approach, which isn’t just metaphorical and narrative but can also be viewed as the building of mythology in a contemporary sense. A work so densely packed with figures and creatures from a post-human era – which is far beyond established concepts of reality and rich in symbols, forms, and themes from esoteric traditions – necessitates a reading that incorporates interpretations from the domains of alchemy, astrologers, and magic.

Recommended Reading

Did you enjoy learning about H. R. Giger’s artwork and life? We could only fit so much info into one article, so if you wish to learn more then consider buying a book about Hans Ruedi Giger! Here is a helpful list of recommended books.

H. R. Giger (2007) by H. R. Giger

H. R. Giger has been one of the most influential figures in amazing art for the past three decades. He gained notoriety as an independent artist after studying interior design for eight years, with projects ranging from surrealistic fantasy land scenery generated with a spray gun and markings to album cover creations for renowned pop artists and sculpting. Giger’s multi-faceted career also involved designing two bars, one in Tokyo and the other in Chur, as well as collaborating on various film productions.

- Detailed commentaries on H. R. Giger's work by the artist himself

- Describes his work from the early 1960s to the present day

- Designed by H. R. Giger himself

H. R. Giger: Alien Diaries (2013) by H. R. Giger

H. R. Giger explains his work at the studios in the transcribed Alien Diaries, which is now available as a facsimile for the first time. With his Polaroid, he writes, draws, and pictures. Giger explains working in the film industry with harsh honesty, cynicism, and even despair, and how he fights against all odds to make his creations become reality, whether it the stinginess of filmmakers or the slowness of his employees. The Alien Diaries provide an uncommon, thorough look into the development of a film classic through the eyes of a Swiss artist, and reveal a little-known private story of the painter H. R. Giger.

- Transcribed "Alien Diaries" published here for the first time

- Shows a little-known personal side of the artist H. R. Giger

H. R. Giger struggled for recognition in both the cinema and art industries, despite the fact that he didn’t fit comfortably into either. Despite being the inspiration for Alien’s antagonist as well as the film’s spacecraft and surroundings, he felt rejected by Hollywood. In the art world, his legacy still has a possibility for expansion. Giger’s carefully crafted pieces are what we really need in an era of mass-produced pictures.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Hans Ruedi Giger?

Hans Ruedi Giger was a Swiss illustrator well known for his airbrushed representations of human bodies combined with technology, so-called the biomechanical style. His Gigeresque artwork was utilized in the special effects for Alien, which won an Academy Award for visual design. The film’s artwork was inspired by HR Giger’s masterpiece Necronomicon IV (1976).

What Inspired H. R. Giger’s Artworks?

Giger’s most significant creative achievement was his representation of human bodies and equipment in icy, connected interactions, which he dubbed as biomechanical. His main influences were Ernst Fuchs, Dado, and Salvador Dalí. Some say his work is dismal and depressing, focusing on death, blood, overpopulation, strange things, and so on, but he disagrees. His biomechanical notions are still being investigated individually in domains such as media art and bio-art, less as an aesthetic influence and more as suggestions for philosophical approaches.

Who Created the Alien Creature?

This unforgettably horrifying extraterrestrial set a new standard for cinematic anguish about interplanetary space and existential dreams—one that, according to some, has yet to be surpassed in the more than 40 years after the film’s debut. The unearthly sculpture has a backstory that dates back to a niche in the art world in the late 1970s. It was designed by H. R. Giger, a then-unknown surrealist artist from Switzerland, who had previously created the on-screen xenomorph in a 1976 artwork named Necronom IV.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “H. R. Giger Art – An In-Depth Exploration of Gigeresque Art.” Art in Context. June 6, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/h-r-giger-art/

Meyer, I. (2022, 6 June). H. R. Giger Art – An In-Depth Exploration of Gigeresque Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/h-r-giger-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “H. R. Giger Art – An In-Depth Exploration of Gigeresque Art.” Art in Context, June 6, 2022. https://artincontext.org/h-r-giger-art/.

Very interesting artile, thank you!