“Salvator Mundi” by Leonardo da Vinci – A Jesus Painting Analysis

The Salvator Mundi (c. 1499-1510) painting has become one of the most mysterious and investigated pieces of art in the world and is subject to scientific, political, and cultural controversies. This article will explore the famous Jesus painting and its peculiar history.

Artist Abstract: Who Was Leonardo da Vinci?

Leonardo da Vinci was born in April 1452 and died in May 1519. He was born in the town called Vinci in Tuscany, Florence in Italy. His father’s name was Piero Fruosino di Antonio da Vinci, and his mother was known as Caterina, who was a peasant.

When he lived in Florence, he worked in the studio and was an apprentice to a well-known Florentine painter of the time, Andrea del Verrocchio from a young age, around 14 or 15 years old, learning various artistic, scientific, and mechanical skills.

He traveled throughout Europe and was commissioned by many notable people including royalty. He was considered a polymath and genius and became one of the most famous artists from the Renaissance era as well as an exemplar of the Humanist ideals that were so prevalent during the Renaissance period. Some of his most famous artworks include The Last Supper (c. 1495 – 1498) and The Mona Lisa (c. 1503 – 1506).

Salvator Mundi (c. 1499 – 1510) by Leonardo da Vinci in Context

We will start this article with a socio-historical overview, discussing the rich and mysterious history of the Renaissance Jesus painting known as Salvator Mundi, which was reportedly painted by Leonardo da Vinci – although many sources have questioned whether the artist really painted it himself.

We will then discuss a formal analysis, looking at the subject matter and stylistic techniques composing the Salvator Mundi painting. We will discuss this according to the framework around the main elements of art, namely color, texture, line, shape, form, and space.

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Date Painted | c. 1499 – 1510 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Genre | Religious painting |

| Period / Movement | High Renaissance |

| Dimensions | 45.4 x 65.6 centimeters |

| Series / Versions | N/A |

| Where Is It Housed? | The exact location is uncertain. |

| What It Is Worth | Sold for $450.3 million in November 2017 to Prince Badr bin Abdullah |

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

The history surrounding Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci is complex and it boasts an extensive timeline of over 500 years. It has been proclaimed as lost, found, copied, restored, authenticated, and sold at auction – a painting that passed through hundreds of hands.

Anyone who wants to understand more about the Salvator Mundi painting and its whereabouts – whether you are an art historian or merely just an art enthusiast who wants to know more – will undoubtedly go down a bit of a “research rabbit hole”.

Therefore, it is important to note and be aware of the extensive research undertaken on this painting, and there are numerous theories and speculations from hundreds of sources – scholarly and public.

We will explore and present the important aspects of this iconic Jesus painting in as much simplicity as possible and although we will not cover all there is to know about it, we encourage you to take the research further and delve deeper into its many mysteries.

Who Commissioned the Salvator Mundi Painting?

There are numerous historians and scholars who have dated Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci, and generally, the dates fall between 1499 to around 1510. One of the leading scholars on the subject is Joanne Snow-Smith, who posited that the famous Jesus painting was commissioned by King Louis XII of France and his wife Anne of Brittany and that it would have been utilized for personal devotion. In the journal article by Snow-Smith titled The Salvator Mundi of Leonardo da Vinci from the Arte Lombarda Nuova Serie (Number 50, 1978) she explains the king’s interest in Da Vinci’s work.

If we look at the painting’s date of creation, Da Vinci was reportedly living in Milan from 1482 to 1499 and traveled throughout Italy until his return to Milan in 1508.

According to Snow-Smith, King Louis XII may have shown interest in Leonardo da Vinci from as early as 1499 due to other artworks he produced, and there was a remuneration to Da Vinci from King Louis XII from around 1507 to around 1513.

However, it has also been suggested by other sources that Da Vinci produced Salvator Mundi when he was in Florence in 1500. Some sources also suggest that Da Vinci was not a painter either while others posit that he had assistants who painted parts of the subject matter.

According to Snow-Smith, after “Salvator Mundi” was completed around 1513, the painting was given to the king’s army and transported from Dijon to Blois, which is reportedly where the king was stationed at the time.

When Anne of Brittany died in 1514, the painting was reportedly given to a convent in Nantes, which is a city in France. This was also where Anne of Brittany was born and raised as well as where her heart was buried after her death.

Salvator Mundi: A Mystifying Provenance

The painting had a complex history during the 17th century, and it has been passed down through many hands, so to say, until the 21st century. It was believed to have come into possession of Queen Henrietta Maria in 1625, who was married to King Charles I. It was reportedly sold to the creditor Captain John Stone at what is known as the “Commonwealth Sale” in 1651 – this was after King Charles was executed in 1649 when all his possessions were sold to repay debts.

However, reportedly during 1660, the painting was returned to King Charles II, which is also referred to as the “Restoration” and added to the Whitehall inventory in 1666.

King Charles II’s successor was King James II, who inherited the painting, which then came into Catherine Sedley’s possession, who was King James II’s mistress. It was then passed down to the Duke of Buckingham who was John Sheffield, and his son Sir Charles Herbert Sheffield placed it on auction around 1763.

Many sources indicate that the painting’s inventory became unclear or not recorded until again in the 1900s, when it was bought by Sir Francis Cook, who was an art collector, from Sir John Charles Robinson. In 1958, it was reportedly sold for £45 at an auction by Sir Francis Cook’s grandson.

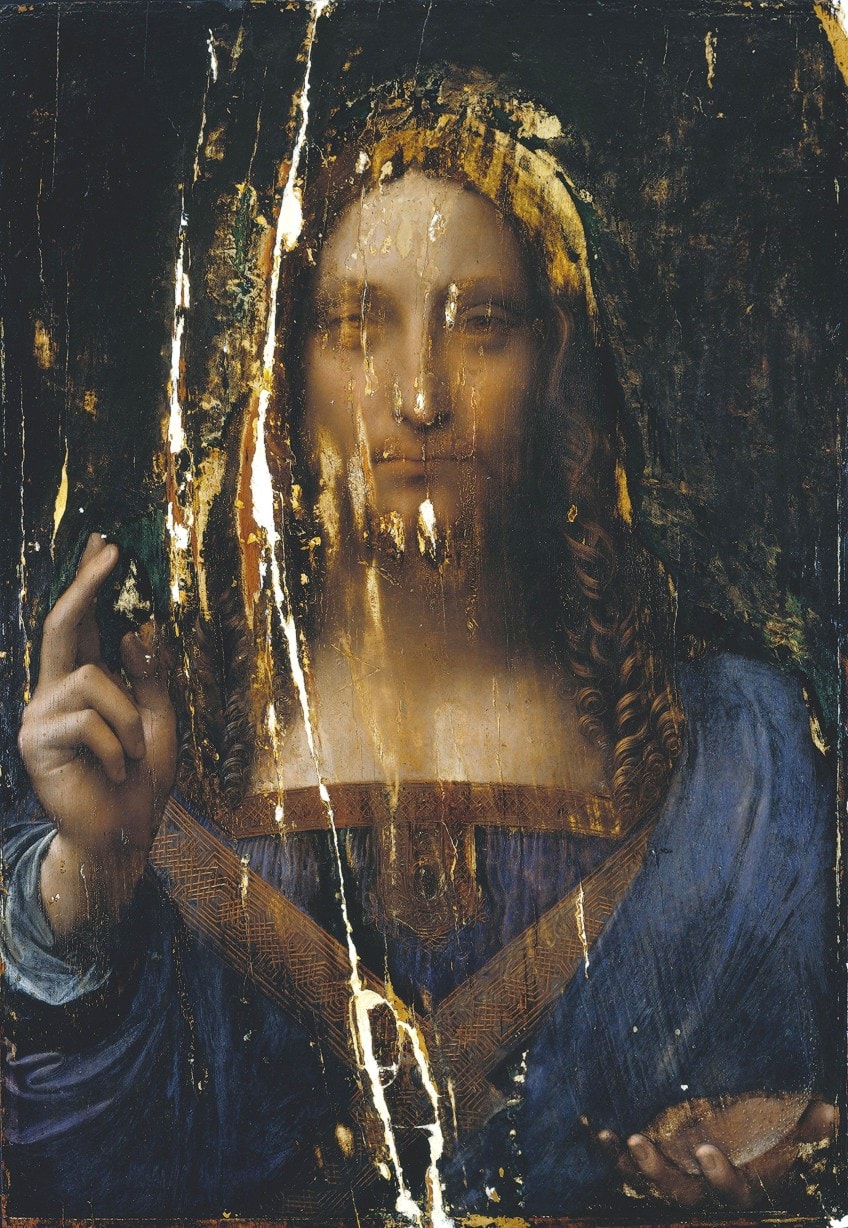

The Salvator Mundi Restoration

Many sources date the painting’s re-emergence to 2005, and when it was sold again, the Salvator Mundi price was $1.175 million, and sold to Robert B. Simon and other art dealers at an auction in New Orleans. Apparently, the painting was, by this time, “overpainted” from years of reconstruction to its surface.

The conservator Dianne Dwyer Modestini was commissioned to restore the long-last Jesus painting. During the restoration process, Modestini discovered a preparatory drawing, otherwise known as a “pentimento” of Jesus Christ’s thumb position, which was changed on the painting.

Along with numerous other discoveries found from infrared technology as well as an analysis done by other scholars, the original face revealed itself. It was also exhibited by the National Gallery in London in 2011 and reportedly also “authenticated” and attributed to being an artwork by Leonardo da Vinci.

Where Exactly Is the Salvator Mundi Painting Now?

Reports indicate that Salvator Mundi was sold again in 2013 at a private sale that was held, or as it is termed “brokered”, by Sotheby’s. The Salvator Mundi price was over $75 million and sold to the Swiss Yves Bouvier who sold it to the Russian Dmitry Rybolovlev for $127.5 million. This resulted in a lengthy dispute between the two dealers as well as a lawsuit against Sotheby’s, which was from 2016 to 2018.

After the above-mentioned events, Salvator Mundi was reportedly sold yet again for a bit over $450 million to Prince Badr bin Abdullah, for whom there have been numerous debates in terms of who he bought it.

Some sources have stated it was for Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and others report that it was for the Abu Dhabi Department of Tourism and Culture to be displayed at the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

In short, allegedly the Louvre Abu Dhabi postponed the display of the famous Jesus painting, and according to various sources, the painting was either in Switzerland in storage or on a yacht that Mohammed bin Salman owned.

Salvator Mundi in the Media

The Salvator Mundi painting has not only been studied extensively but has become the topic for several documentaries, namely The Savior for Sale (2021), directed by Antoine Vitkine, and The Lost Leonardo (2021) directed by Andreas Koefoed.

Both films explore the intricate history of the “Salvator Mundi” painting and its rise in monetary value over the years of being sold.

Formal Analysis: A Brief Compositional Overview

Below, we will discuss a visual description of the subject matter of Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci, as well as some of the stylistic compositional aspects like color, texture, line, shape, form, and space.

Visual Description: Subject Matter

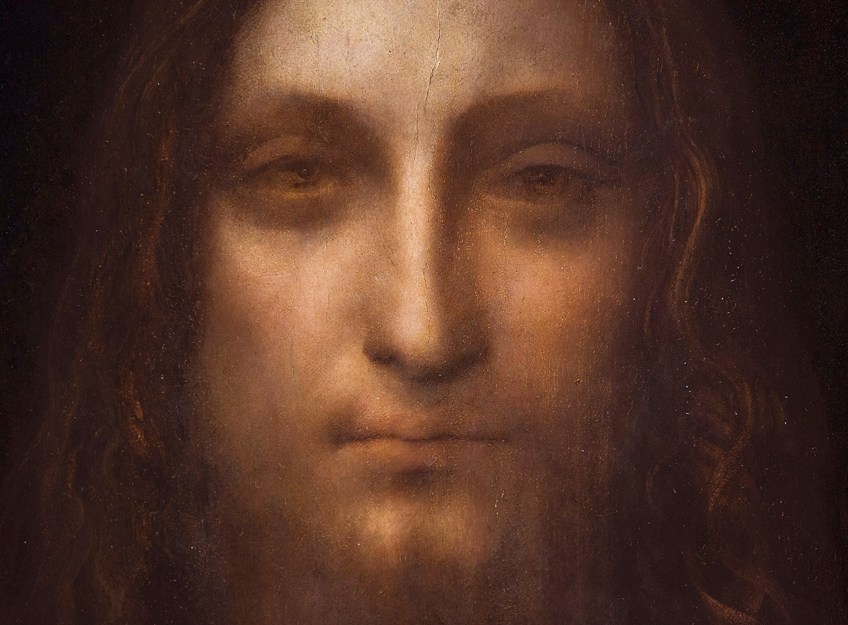

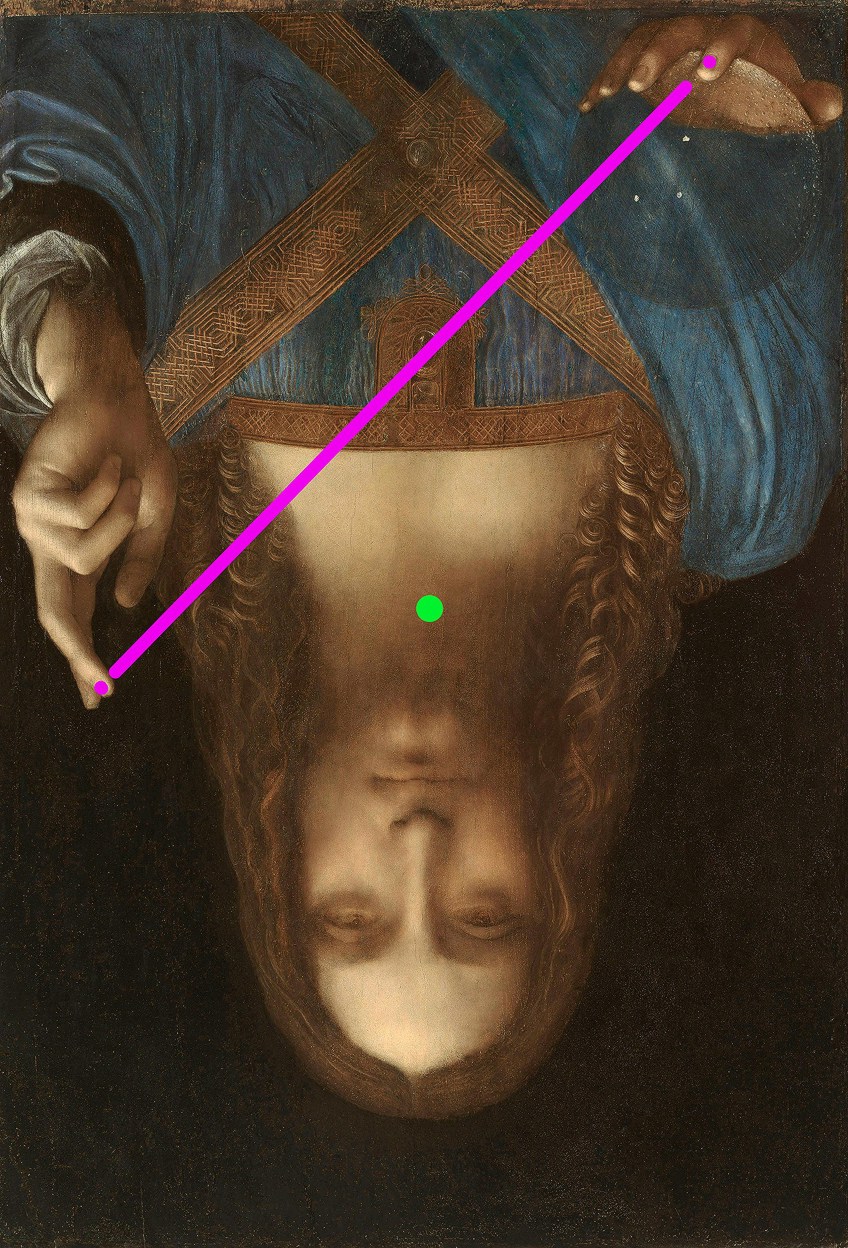

The Salvator Mundi painting depicts a frontal portrait view of Jesus Christ, depicting the top half of his torso, shoulders, and head. The background is dark in color and appears to be black. He is looking directly at us, the viewers, with a gentle yet penetrating gaze. His right hand (our left) is raised to just above chest height with his index finger and middle fingers both raised in a gesture of blessing.

In His left hand (our right), there is a large orb, which is held level with His chest.

Christ is wearing a blue robe lined with golden zig-zagged and interweaved patterned trims; His robe appears to be from the Renaissance clothing fashion. His hair is a dark brown color and falls just below his shoulders in detailed curls.

What Does “Salvator Mundi” Mean?

To better understand why Jesus Christ is portrayed the way He is in the Salvator Mundi painting, we need to understand the context around this specific type of portrayal. It relates to what is known as “Christian iconography” and the title also provides us with more information because the words Salvator Mundi are Latin meaning “Savior of the World”.

In Christian iconography, the image of Jesus Christ with a raised right hand and left hand holding an orb is a common depiction. It reportedly dates to the Byzantine era but has been attributed to numerous Northern Renaissance painters who originally utilized the subject matter before Italian artists depicted it too.

The orb we see in Christ’s left hand is usually depicted with a cross attached to the top of it, however, in Da Vinci’s rendering, the orb is without the cross. The orb is referred to as globus cruciger and is usually translated to “cross-bearing globe” in Latin. The globe is symbolic of the earth and the cross symbolizes Jesus Christ as the “ruler” of the earth – otherwise also as Christianity ruling the earth.

The overall symbolic meaning of Jesus Christ holding the orb and raising his right hand could refer to a blessing, otherwise known as a benediction, and the idea that He is the Savior of the world.

The Case of Leonardo da Vinci’s Orb

The orb in the Salvator Mundi painting has become a topic of scholarly and scientific debate and is worth mentioning here. During the Salvator Mundi restoration, many scholars have looked at Da Vinci’s rendition of the orb in Jesus Christ’s left hand (our right), questioning its realism because it did not refract light the way it would in real life, and the robe behind the orb appears differently than would be expected if it were a solid orb.

This was also questioned because of Da Vinci’s reputation for having a scientific mind – he would have understood optics and how light reflects and refracts because of his own research and studies about it.

Some have suggested that Da Vinci chose to leave out these realistic details and others like the renowned Da Vinci scholar Martin Kemp suggested that Da Vinci did seek to portray all the minute details of nature, exactly as he saw it, but a visual representation of it. Kemp also stated that it would have appeared “grotesque” to depict all the details in a “devotional image”.

According to the extensive scientific analysis and research done on the orb, the paper titled On the Optical Accuracy of the Salvator Mundi (2019) by Marco (Zhanhang) Liang, Michael T. Goodrich, and Shuang Zhao posits that the orb is hollow and not a solid crystalline rock based on studying how a hollow orb would distort straight lines.

Color

Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci is not a bright painting and appears more muted in its color scheme. At first glance, we see soft hues of blues, browns, and fleshy tones. However, this Jesus painting has undergone scientific study during its restoration and according to a stereomicroscopic study, some of the color pigments were identified, although it was also noted that there could be other unidentified pigments.

Some of the noted pigments in “Salvator Mundi” include bone blacks, charcoal, lead white, vermilion, red lake, red iron oxide earth, lead-tin yellow, natural ultramarine, umber, and carbon.

The pigments were also reportedly applied in painted layers to achieve different shading and lighting effects, for example, the flesh tones were reportedly started with “brighter” colors, which were then layered, similarly, the drapery was started with darker shades.

We also see techniques like sfumato utilized with notable light and dark transitions; for example, in Jesus Christ’s neck area, there is considerable shading below his chin that becomes lighter as it moves downwards to his upper chest area. We will also notice this delicate shading on His face too, which gives the composition a natural yet striking appearance.

Texture

There are various textures in the Salvator Mundi painting, and most of these are implied textures ranging from soft to hard. Examples include Jesus Christ’s skin, which appears perfectly smooth and seemingly untouched; the curled locks of His hair appear soft framing his face. We also see contrasting textures on the patterned trims on the edges of His blue robe as well as the softer folds of His robe.

There is also an implied texture of the orb in Jesus Christ’s left hand (our right), which appears translucent and hard in its crystalline and glass-like material.

Line

There are several examples of vertical lines in Salvator Mundi, for example, the vertical portrait orientation of Jesus Christ’s figure, which is further implied by His pointed fingers of his right hand (our left). His straight hair and the folds of his robe also create vertical and curved lines; however, these are seemingly contrasted with the horizontal and crossed lines created by the trimming on His robe.

Shape and Form

There are several examples of how shape and form are depicted in the Salvator Mundi painting. The overall form of the painting could be said to be organic as it is a naturalistic or figurative rendering of the subject matter.

Some notable examples include the spherical forms like the orb in Jesus Christ’s left hand (our right), the organic circular and curved shapes from the curls of His hair, and more geometric shapes from the patterns and trimming on His robe.

Space

Space as an art element refers to how the area within a visual composition is utilized as well as how the illusion of depth of three-dimensionality is depicted, which can also tie in with perspective and scale. In Salvator Mundi, the figure of Jesus Christ fills most of the compositional space and the darkened background creates emphasis on His figure even more.

With other art elements like color and how it is utilized through shading and highlighting, especially on the skin tones, more depth is created.

Salvator Mundi: Untangling an Art Mystery

In this article, we explored the riveting and rather lengthy history and provenance of the Salvator Mundi painting. It has also been known as the “male Mona Lisa” and is one of the most expensive paintings sold; it is one of the most mysterious paintings from the Italian Renaissance.

While there has been extensive historical and scientific analysis done on it to determine its true origins there are nonetheless unanswered questions surrounding it – being one the largest art crime mysteries – and we are left with a trail of inconsistencies that ultimately lead us to ask what the truth is.

In conclusion, to understand this painting on a deeper level is to also understand Leonardo da Vinci and what his style was as an artist – many sources question whether Da Vinci was the true artist or only painted part of the “Salvator Mundi” subject matter, but others stand fast that the Renaissance artist was indeed the man behind the paintbrush. Maybe this is an art mystery that will never really be completely untangled.

Take a look at our Salvator Mundi painting webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Painted Salvator Mundi?

The Salvator Mundi painting was created by the Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci somewhere between 1499 to 1510. Many have debated the accuracy of who painted it due to stylistic differences in parts of the subject matter. It is believed that Da Vinci had assistants who helped him.

Who Bought Salvator Mundi?

The Salvator Mundi (c. 1499-1510) painting has a long history, and it has been sold several times throughout the centuries, however, the latest sale went for just over $450 million to Prince Badr bin Abdullah who bought Salvator Mundi – allegedly – for the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Where Is Salvator Mundi Now?

The whereabouts of the Salvator Mundi (c. 1499-1510) painting are mysterious and uncertain. Some say it is held in storage or hidden, placing it in Switzerland or Saudi Arabia and others posit it is on a yacht that is owned by the Saudi Prince.

What Are the Documentaries About Salvator Mundi?

There are two well-known documentaries about the Salvator Mundi (c. 1499 to 1510) painting by Leonardo da Vinci, namely The Lost Leonardo (2021), which was directed by Andreas Koefoed and premiered on June 13 at the Tribeca Film Festival. The other documentary is The Savior for Sale (2021), which was directed by Antoine Vitkine.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““Salvator Mundi” by Leonardo da Vinci – A Jesus Painting Analysis.” Art in Context. August 3, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/salvator-mundi-by-leonardo-da-vinci/

du Plessis, A. (2022, 3 August). “Salvator Mundi” by Leonardo da Vinci – A Jesus Painting Analysis. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/salvator-mundi-by-leonardo-da-vinci/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““Salvator Mundi” by Leonardo da Vinci – A Jesus Painting Analysis.” Art in Context, August 3, 2022. https://artincontext.org/salvator-mundi-by-leonardo-da-vinci/.