Jan van Eyck Paintings – Looking at the Best Jan van Eyck Artworks

Jan van Eyck’s paintings represented early innovations in the burgeoning Northern Renaissance and Netherlandish movements. Despite being a highly respected figure, certain aspects of his life remain shrouded in mystery, such as his birth date. Jan van Eyck’s oil paintings were regarded as some of the best examples of the emerging painting medium, with some historians going as far as to say that he pioneered the technique of using oil in painting. He was not the first, however, he did raise the bar and set new standards that helped bring it to popular consciousness.

Our List of Important Jan van Eyck Paintings

The effect of Jan van Eyck’s artworks has been so enormous that it is nearly pointless to talk about oil painting without mentioning him. The 15th-century artist passed away in 1441, most possibly in his early 50s, leaving behind little over 20 oil works. His art still fascinates people today, as indicated by the fact that an anthropomorphic lamb depicted in his famous Ghent Altarpiece became an unforeseen online global phenomenon.

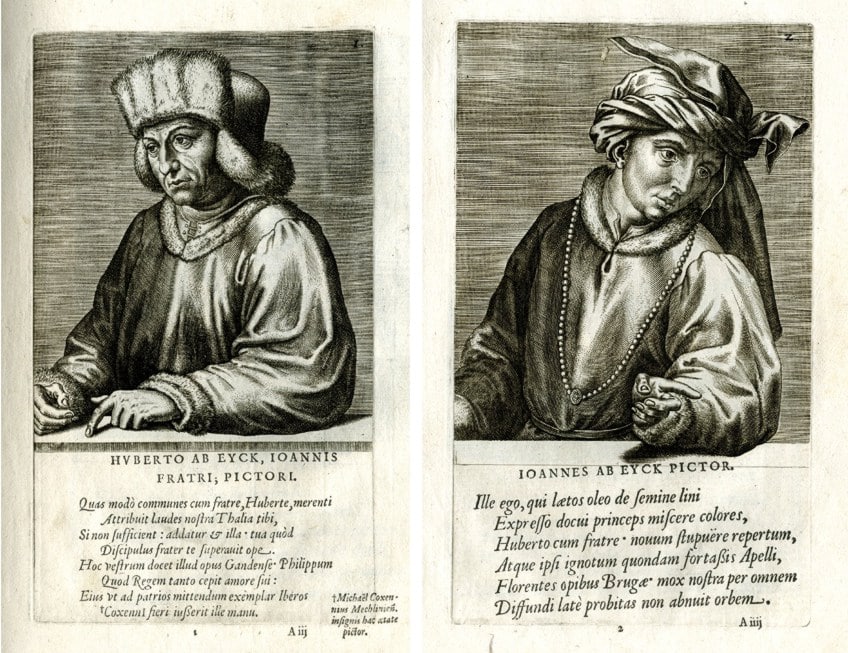

Jan van Eyck is the most well-known member of a painting family said to have arisen in the town of Maaseik.

Hubert, van Eyck’s brother, is said to have taken the responsibility for van Eyck’s artistic instruction and made him his younger apprentice at home. Van Eyck worked at two courts, gaining a prominent post with Philip the Good and serving for John of Bavaria. Occupation at court gave him a prominent social position that was rare for an artist, as well as creative autonomy from the Bruges artists’ guild.

Many components of his work were undoubtedly meant to enhance his own name and talents, particularly his habit of signing and dating his photographs, which was regarded odd at the time. His creative reputation is based in part on his unequaled ability in visual illusionism. His ability to control the characteristics of the oil medium was critical in achieving such results.

Critics have professed amazement and surprise at his ability to replicate reality, especially the impact of light on diverse substrates, ranging from drab reflections on opaque surfaces to brilliant, changing highlights on metals or glass, since the 14th century.

Saint Francis of Assisi Receiving the Stigmata (1430)

| Date Completed | 1430 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 12 cm x 14 cm |

| Currently Housed | Philadelphia Museum of Art |

Jan van Eyck is regarded as a realism pioneer, not just for his precise portraits but also for his breathtaking scenic landscapes that seem to fade far into the horizon. Artwork such as Saint Francis of Assisi predates Leonardo da Vinci’s realistic settings by more than 50 years.

This Jan van Eyck oil painting exemplifies Eyckian atmospheric viewpoint and foreshadows the later style of the Baroque Dutch landscape genre. Jan van Eyck set this scenario amid the myth’s rocky mountains, but he also inserted a small busy Netherlandish town in the background using his minuscule painting style, which was a typical feature of early Netherlandish artworks about the scriptures.

This tiny artwork represents an important event during Francis of Assisi’s 40-day fast in the solitude of Mount Penna when the monk had a revelation and acquired the stigmata.

The stigmata, something that never fades, became a visible reminder of his sanctity. The crucified Christ looks down on the priests, Leo and Francis, who are dressed in the tan and grey robes that designate them as Franciscans. The tired individuals, on the other hand, have been regarded as physically ungainly, and the two priests are not properly integrated into the environment (they may have been done by helpers in the artist’s studio).

Miniature paintings like this one were created to celebrate a fruitful journey or as a mobile religious item to escort a believer on a voyage.

Though van Eyck’s depiction of this tale adheres to the traditional Franciscan narrative to the letter, as a historian put it, “the scenario is depicted as a wonder being observed within the framework of the full sweep of humans and natural existence.” This is one of the first paintings in Northern Renaissance art showing the life of Saint Francis of Assisi. The artwork was re-attributed to van Eyck for the first time in 1857, a few years before it was revealed to have been referenced in Anselm Adornes’ 1470 bequest.

Portrait of a Man with a Blue Chaperon (1430)

| Date Completed | 1430 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 22 cm x 16 cm |

| Currently Housed | Muzeul Național de Certă, Bucharest |

This modest oil painting exemplifies the components that are common in van Eyck’s non-religious portrait paintings: the creative three-quarters pose against a black, plain backdrop, a deep sense of illumination emphasizing the model’s identifying features, and the artist’s astounding capacity to capture the multitude of textures of various textiles.

The sitter’s focus is steady, but contemplative, as he stares directly ahead, almost unconscious of the audience’s presence.

Maybe most noticeable is van Eyck’s meticulous consideration of the subtlety of flesh hues in the man’s hands and facial appearance, especially the wispy stubble of one or two days’ regrowth, a recurring element in van Eyck’s early portrait paintings.

The person’s left hand looks to be laying on a wall that was formerly a decorated border. In his right hand, he clutches a band that extends out of the frame into the audience’s environment. The empty frame is where the painter would normally date and sign his piece, making this sample a highly probable but not indisputable instance of his early painting technique. The sitter’s somewhat large head wears the extremely popular, if only for a brief time, turquoise blue chaperon, which serves to place the picture to around 1430.

Portrait paintings like this were produced for a number of reasons, including commemoration of an occasion, occupation, or in commemoration.

This piece, which was first considered to portray a goldsmith, is now commonly regarded to represent a style of painting disseminated to propose marriage. The work’s small size lends support to this notion since it might be packaged and delivered to the bride’s family. Jan’s work was hard to duplicate because of the exactness of details and extremely delicate separation between the characteristics of textures and light sources. Every element of existence has been meticulously planned in order to showcase the majesty of God’s creation.

The Ghent Altarpiece (1432)

| Date Completed | 1432 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 350 cm x 460 cm |

| Currently Housed | The Cathedral of St. Bavo, Ghent, Belgium |

The Ghent Altarpiece is a massive polyptych artwork focusing on Triumph and Redemption themes. It is also a piece with a problematic past since it is the most looted painting in existence. Furthermore, after nearly 400 years of being regarded as Jan van Eyck’s masterwork, a revelation in 1823 called this claim into question. Paradoxically, it was van Eyck’s own handwriting that called this into doubt, with a dedication that reads, “The artist Hubert van Eyck, better than whom no one is to be seen, started the work; Jan, the second sibling, with skill concluded it.”

This final line can alternatively be rendered as “Jan, his next in artistry, finished it.”

The dedication was confirmed as Jan van Eyck’s in 2016, and later found documents link Hubert to two preparatory designs presented to the Ghent council, confirming that he commenced the contract in the early 1420s. After Hubert’s demise in 1426, development on the altarpiece was resumed under the direction of Jan van Eyck until, according to the dedication, “Joos Vijd covered the costs of the project. On the 6th of May, you are encouraged to consider this artwork by this statement.”

Most historians believe that recognition for this significant achievement should be divided between the two men; nevertheless, where the boundary separating their individual contributions is set continues to be a point of contention.

Jan van Eycks’ blend of endless intricacy and majestic grandeur in The Ghent Altarpiece is an awesome accomplishment. The altarpiece is made up of 24 distinct panels, with 12 varying panels visible depending on whether the altar is closed or open.

The Annunciation is the major topic of the closed altar, which is depicted over many screens in the middle layer, within a somewhat ascetic chamber that is sometimes referred to as a convent. The angel Gabriel has just spoken the sentence painted in gold on the paneling, which translated to, “Hail who art truly a blessing, the King is with us, and the Virgin Mary’s response, inscribed upside down as if seen from above, says, “Look the handmaiden of the Divine.”

Man in a Red Turban (1433)

| Date Completed | 1433 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 26 cm x 19 cm |

| Currently Housed | National Gallery, London |

Van Eyck was one of the first painters in Northern Europe to create a greater volume of non-religious portraits of noble and middle-class clients, a style traditionally restricted for society’s governing elite. Van Eyck’s portraits were not only extremely thorough, but he also pioneered a now-common pose, the three-quarter perspective.

It was usual for the person in religious paintings and representations of the monarchy to face the spectator squarely. In Italy, the humanistic environment of the growing Renaissance era witnessed a surge in secular portraiture; benefactors were most commonly portrayed in profile, presumably as a reference to antiquity.

This picture is the most valuable of his existing portraits, and it is widely accepted that it marks another emerging genre at that time – the self-portrait and that this is a van Eyck self-portrait.

This claim is supported not just by the location, but also by the frame, which is inscribed with his motto “As I can”, which is taken from a proverb. Therefore, the message blends accomplishment’s pride with humility. The inclusion of a life mantra is a feature generally associated with the noble and governing elites, and it also suggests the painter’s exalted position. Only a handful of Jan van Eyck’s artworks, one being a portrait of his bride, did he include his motto.

This could imply that the subject of the picture is a close family member or possibly the painter himself.

In conjunction with the subtle details, the artist’s straight stare at the audience shows his earnest attention as he makes a piece in his own likeness, with his arms out of sight, preoccupied with the work itself. Since the Renaissance, the subgenre of the self-portrait has served as a business card for painters, allowing them to exhibit their skills and creative flair. The intricate placement of the red chaperon, which is perhaps a feature by which the painter may be recognized in other van Eyck self-portraits, allows the artist to demonstrate his flawless skill.

The Arnolfini Portrait (1434)

| Date Completed | 1434 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 82 cm x 60 cm |

| Currently Housed | The National Gallery, London |

Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait is one of the most recognized artworks in Europe’s history of art. Whereas The Ghent Altarpiece was globally recognized at the time it was created, this piece was not well recognized until more than a hundred years after it was completed. The full-length dual portrait, in and of itself an oddity, portrays a rich man and youthful females holding hands in a shadowy environment. As he looks somewhat to his left, the man’s right hand is lifted, as if in welcome or swearing a vow. The female, her head slightly bowed, glances at him in the eyes.

The delicate interaction of light and shade creates a peaceful closeness.

The regulated amount of lighting, such as that entering through the glass to the audience’s left, and shadowing served to unite the arrangement, which is a hallmark of early Flemish painting’s distinctive realism. The tremendous dexterity of artistry on show, most notably in the golden light fixture and curved mirror against the rear wall, confirms Jan van Eyck’s designation as the “King of Oil Painting.”

Full-length portraiture was very uncommon in the early Renaissance, but it eventually proved to have a significant impact on many periods of painters. Nevertheless, Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait remains a source of debate among researchers and academics as to the details about how this artwork was commissioned.

A recorded assessment of Margaret of Hungary’s collections in 1516 mentioned: “A huge picture which is named Hernoult le Fin with his bride in a bedroom produced by Johannes the artist.” But, whose relative of the Arnolfini clan and the name of the female remained a mystery for a long time. Each element in the picture was imbued with allegorical meaning. The term “disguise” was not intended to imply that the message was concealed from its current audience.

On the contrary, it was believed that they would grasp the imagery’s double meaning, but that instead of conventional or classical iconography, the artist used commonplace things to express meanings based on a generally held understanding of specific analogies.

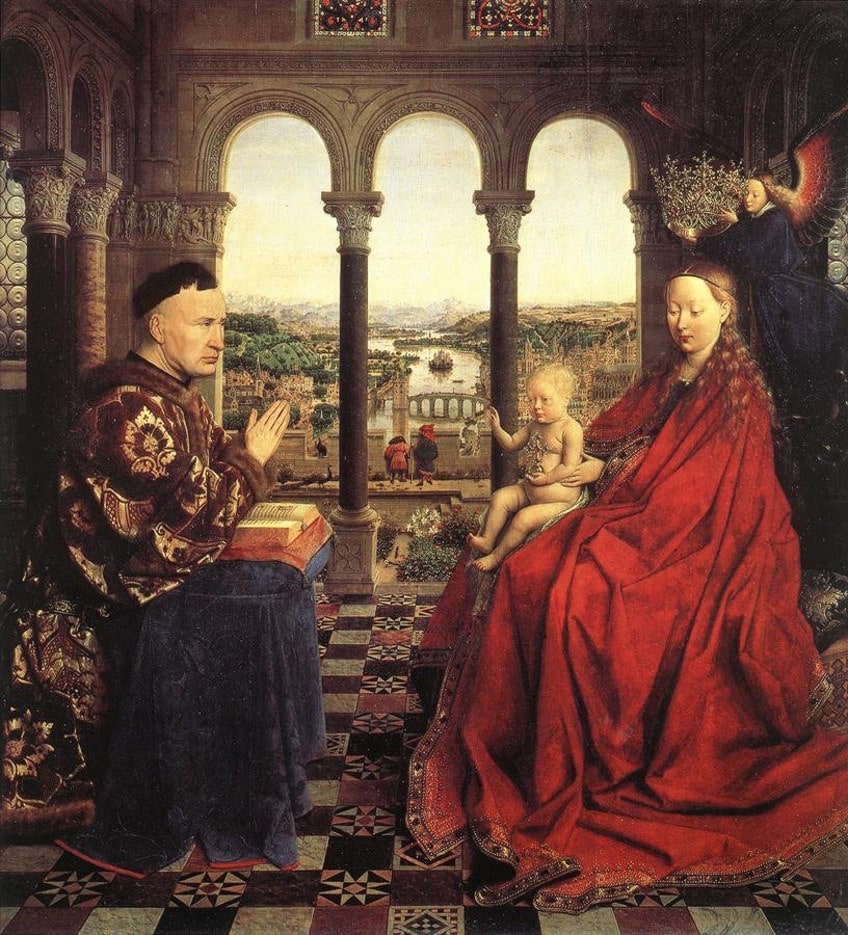

The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin (1435)

| Date Completed | 1435 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 66 cm x 62 cm |

| Currently Housed | Louvre Museum, Paris |

All through his professional life, Jan van Eyck created a large number of artworks. Nicolas Rolin, a prominent person, and benefactor of the art forms in the Netherlands commissioned this representation of a recipient appearing to welcome the Madonna and Christ Child. Rolin was Chancellor to Philip the Good and possessed several wineries in Autun.

This artwork is an instance of the “holy discussion” tradition, where the topic became increasingly fashionable. It could also be interpreted as the portrait of Nicolas Rolin’s benefactor.

Van Eyck’s compelling naturalism in three-quarters, full-length portraiture superseded the old tradition’s rigid frontality. It was created for the chancellor’s church building in Autun, Notre-Dame-du-Chastel, where it hung until the building burned to the ground in 1793. Following a brief stay at the Autun Cathedral, it was relocated to the Louvre in 1805. The symbology of The Rolin Madonna is as intricate as that of The Arnolfini Portrait, and the concept of “hidden allegory” equally applies here.

There are blatant and intimate connections to both the Old and New Testaments, adding levels of significance to the characters.

The somber chancellor is portrayed bowing to adore the Baby Jesus and Virgin Mary, clothed in a gold silk gown adorned with mink fur. The important role of Mary, Christ’s mother, is highlighted by her lavishly adorned velvet gown, with needlework echoing the wonders of existence, and magnificent studded royal headdress borne by a cherub with rainbow-colored feathers, symbolizing the connection between heaven and earth.

Jesus bestows a blessing on Rolin while clutching a silver ball signifying the earth and a golden crucifix as a reminder of his worldly and metaphysical sovereignty over all things. Three Romanesque arches aesthetically connect the statues while also referencing the Holy Trinity. The etched sculptures on the column’s capital portray episodes from Genesis to the fall of humanity and exile from Eden.

As a result, the story progresses from worldly vice, as exemplified by Nicolas Rolin, to heavenly mercy and redemption, as portrayed by the holy figures, from side to side.

The Annunciation (1436)

| Date Completed | 1436 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 90 cm x 34 cm |

| Currently Housed | National Gallery of Art, Washington |

This Jan van Eyck oil painting has a lengthy history, dating back over 580 years. The piece was originally produced on a wood panel before being moved to canvas. Then, throughout time, there were a few preservation efforts. The artwork is currently on display in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where it has undergone additional conservation work. Restorers must make tough judgments regarding what to repair and what to retain to reflect the painting’s history while preserving artworks.

When a piece is this significant, its preservation process becomes a part of its story.

As we analyze this picture there is much to enjoy in regards to its aesthetic features, the arrangement, the hues, the lighting, we can get distracted, but to fully grasp what Van Eyck has done, we require historical and theological background. We may take our admiration to a whole new level with those resources.

Many of the signs in this piece are recognizable from earlier Annunciation artworks, while others are specific to this piece. Van Eyck’s schooling is evident in the doctrine he has crammed in. Mary is dressed in the hue of the divine, blue. This is essentially a reinforcement to Mary that she holds the almighty (Christ) inside her.

The Annunciation is the occasion of conception in Religious theology, and Mary is typically dressed in a blue gown to inform the observer that the Lord has come to the earthly plain and assumed the form of a human. The angel Gabriel is dressed opulently and bears a halo to emphasize that he is heavenly and not of this world. The headdress and garments of Gabriel are studded with diamonds.

The grandeur of the cloth juxtaposes with the simple blue of Mary’s gown, emphasizing the separation of earth and heaven. The hieratic scale has also been utilized, which implies that Mary and Gabriel are significantly bigger than they ought to be considering the building’s size. A hieratic scale is a mechanism used to demonstrate the significance of specific figures.

The metaphoric message conveyed by the angel and Mary takes precedence over naturalism in this painting.

Saint Barbara (1437)

| Date Completed | 1437 |

| Medium | Drawing on Panel |

| Dimensions | 34 cm x 18 cm |

| Currently Housed | Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium |

Jan van Eyck’s painting Saint Barbara is a later piece that is exceptionally different from his recognized works. It is a sketch in silverpoint using lighter colors in oils and dark pigment on a chalk and horse glue base, not a completed picture. Silverpoint is a classic media that has been used since medieval times and was especially prominent during the Renaissance. It’s also tough to perfect since no lines can be removed and no genuine black can be obtained. Consequently, it was not utilized as a drawing material, but rather for finer outlines and as an initial layer for artworks.

Despite the fact that certain areas are colored and others are merely sketched, van Eyck had already marked the piece, presenting yet another conundrum in his body of work: Is it a completed or uncompleted sketch… or painting?

In any instance, it is a first for the painter as the oldest surviving sketch that is not on parchment or paper, or the oldest unfinished painting on a panel that is still intact. The data does show that the Flemish thought art to be a valuable thing in and of itself. It might be the piece that Karel van Mander, a Flemish artist, art critic, who some consider the Northern counterpart of Giorgio Vasari, commended in the early 1600s as “more accurately and perfectly created than the final artworks of other artists ever could be.”

Friedrich Winkler, a German art expert, claims it is a completed piece since no preparatory sketch would include such intricate detail, and he references two 15th-century paintings of Mary that were undoubtedly incomplete at the date of the artist’s demise.

The painting shows a youthful Saint Barbara, a lady of Syrian ancestry who lived during the time of Emperor Maximian, soon before Christianity was embraced by Romans under Constantine’s authority. Her attractiveness was so stunning, according to tradition, that her parents imprisoned her to keep her protected, permitting only him and those under his judgment to access her. Her dad eventually permitted her to exit the building after years of solitude and her denial of all admirers.

The Madonna in the Church (1440)

| Date Completed | 1440 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 63 cm x 48 cm |

| Currently Housed | Gemaldegalerie, Berlin |

The inside of a beautiful Gothic cathedral is illuminated by a stunning sight of the Virgin Madonna and Child. Most art scholars agree this painting was the left wing of a disassembled and previously looted diptych; its opposite side was likely a devotional image.

The Madonna is represented as the Queen of the heavens in the last frame, bearing a majestic jewel-studded headdress and clad in imperial regalia, a crimson gown indicative of Christ’s impending suffering draped by a royal blue cloak trimmed with gold stitching. She caresses the Baby Jesus, who behaves merely as a kid in his mother’s loving embrace, in a manner reminiscent of the Eleusa symbol from the 13th-century Byzantine traditions.

On the surface, it appears that van Eyck has turned a sacred theme, Madonna and Child, into a virtually liberal, though majestic, figure. Yet, a deeper look tells a lot about van Eyck’s method.

Discussions of Jan van Eyck’s artistic technique generally center on the remarkably high level of naturalism he attained, which was previously unheard of in paintings. Nevertheless, not everything in these pieces is as it looks. Despite their apparent impression of form, the majority of the church interior shown in his religious artworks are entirely fictitious.

Van Eyck manipulates apparent reality to achieve his goals. Realistic items are not depicted apart from symbolism. His accurate portrayal is meticulously refined; nevertheless, it is not authentically informative at all.

The wealth of metaphorical features in van Eyck’s structural décor, such as sculpted images from the Virgin’s lifetime on the choir screens, the wood figure of the Madonna and Child, and winged angels singing hymns from a songbook in a passageway to the observer’s right. When one examines the unique features of The Madonna in the Church, this becomes clear. The size of the Madonna and Child, for instance, is out of scale in relation to her environment; she towers above even the magnificent arcade arches.

The Crucifixion; The Last Judgment (1441)

| Date Completed | 1441 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 56 cm x 19 cm |

| Currently Housed | Metropolitan Museum of Art |

The Crucifixion and The Last Judgment Diptych, the last piece in our list of Jan van Eyck’s artworks, is made up of two tiny painted panels, with sections completed by colleagues of his studio. This diptych is well-known for its elaborate and extremely detailed symbolism, as well as the technical ability required to complete it. It was created on a small scale and was assigned for personal dedication. The original gilt frames feature Latin texts from the Bible.

The Crucifixion is depicted in the leftmost panel, with a distant perspective of Jerusalem.

It depicts Christ’s disciples weeping in the front, soldiers, and onlookers encircling the cross in the middle ground, and three executed corpses in the upper third of the picture. Crucifixion was a cruel type of death sentence wherein the prisoner was bound or hammered to a huge wooden cross and left to suffer for several days before dying. The story of Jesus’ crucifixion is essential to Christianity, and the crucifixion is the major religious emblem for many Christian denominations.

The image on the right depicts images from the Last Judgment.

It depicts a hellish landscape at the bottom, the risen waiting verdict in the middle, and Christ surrounded by apostles, disciples, priests, and aristocracy in the upper third. Verses in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew may also be seen in the upper third of the artwork. The Last Judgment is a central concept in the three major Abrahamic religions: Islamic, Jewish, and Christian. It reflects a destiny-based viewpoint in which our universe concludes with the revival of the deceased and the last judgment of every one of us.

And that concludes our list of important Jan van Eyck Paintings. It is now easy to understand why he was such an influential and important figure – not only in his lifetime but for hundreds of years afterward. Van Eyck’s ability to visualize difficult religious themes made him famous among his day’s well-educated customers.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did van Eyck Really Invent Oil Painting?

It has been a long-living “fact” that Jan van Eyck was the inventor of the medium. However, the long-held belief that Jan van Eyck invented oil painting has long been debunked. Drying oils had been employed as pigment binders in paintings for millennia before can Eyck even picked up his paintbrush.

Why Were Jan Van Eyck’s Oil Paintings So Famous?

Jan van Eyck’s paintings were a perfect representation of the new medium of painting – oil painting. His perfection of this medium was a large factor in the spread of oil painting’s popularity. His adoption of the medium greatly changed the direction of the art of painting.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Jan van Eyck Paintings – Looking at the Best Jan van Eyck Artworks.” Art in Context. October 13, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/jan-van-eyck-paintings/

Meyer, I. (2021, 13 October). Jan van Eyck Paintings – Looking at the Best Jan van Eyck Artworks. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/jan-van-eyck-paintings/

Meyer, Isabella. “Jan van Eyck Paintings – Looking at the Best Jan van Eyck Artworks.” Art in Context, October 13, 2021. https://artincontext.org/jan-van-eyck-paintings/.