Gesamtkunstwerk – Explore Gesamtkunstwerk in Architecture and Art

What is Gesamtkunstwerk? The German Gesamtkunstwerk definition, approximately translated, means “total work of art”, which refers to an artwork, concept, or creative technique in which several art disciplines are merged to make a single coherent whole. The composer Richard Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk ideas popularized the concept, arguing for the quintessential art of the future, in which no rich talent of the different arts would remain untapped in the Gesamtkunstwerk of the years ahead.

Understanding Gesamtkunstwerk

The notion, which is still most popular in Austria and Germany, was developed during the 19th and early 20th centuries by a variety of European art groups and became a basic principle of modern art. Although it went out of popularity during the postmodern era, the phrase is still used to characterize multimedia installations and pieces today.

Gesamtkunstwerk endures most notably in architecture, where all components of the structure; internal, external, and furniture were made to match one another, and this impact can be observed in many movements’ creative practices.

Early Trends

Gesamtkunstwerk’s concepts may be traced back to the Baroque period. Architecture, interior decorating, landscape design, sculpting, and art were all integrated to create a grandiose impact that was mirrored in every detail, from tableware to fabrics.

Later, architects and painters who expanded the royal estates proceeded to aim for a comprehensive impression, while also reflecting the effect of subsequent styles.

This may still be observed in Rococo architect Nicolaus Pacassi’s renovations to Schönbrunn Palace. In 1996, UNESCO designated Schönbrunn Palace as a World Heritage Site, describing the structures and gardens as “a spectacular Baroque ensemble and a great illustration of Gesamtkunstwerk,” illustrating how beautifully Pacassi’s work integrates with the original.

German Romanticism

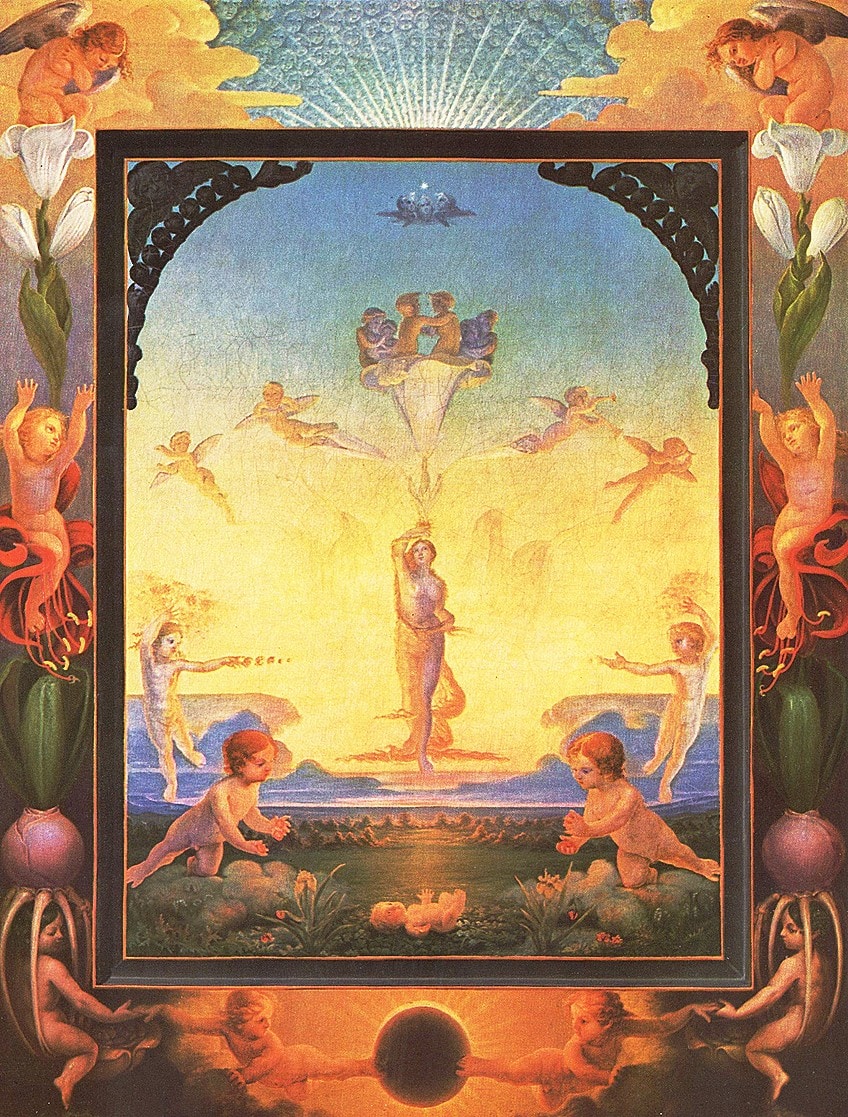

The Romanticism movement of the early 19th century affected the creation of Gesamtkunstwerk, most significantly through the artist and thinker Philipp Otto Runge. Runge is well known for his Tageszeiten (1803 – 1805) series, which showed various periods of the day as a holistic conception of humans, natural elements, architectural elements, and landscapes.

Taken as a type of forerunner of Gesamtkunstwerk, Runge’s works had a significant effect on German painters, especially after Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the prominent personality of the day, became a patron.

Richard Wagner

In his Aesthetic or Theory of Worldview and Art, K.F.E. Trahndorff, a German writer and philosopher, used the term Gesamtkunstwerk in 1827. Although he was the first to use the word, he expanded on the ideas of previous philosophers who pushed for a synergy of the arts, such as Ludwig Trek and Gottfried Lessing.

Richard Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk was promoted by intellectually adopting the word and embodying it in his famed operas, to the point that it was commonly credited to him.

His articles stated that the arts had been inextricably divided from one another since the ancient Greeks, and that future artwork must return to making a comprehensive piece of art. Wagner saw the nineteenth century as chaotic, and he stated, “It is for Art above everything else, to educate this social force its purest meaning, and steer it towards its right goal.” His celebrated opera cycles, notably Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), established him as the most famous and influential composer of his day, combining drama, literature, song, and dramatic setting to create a coherent experience.

He also designed and built the Bayreuth Theatre in Bavaria in 1857, establishing a full atmosphere for the staging of his opera cycles.

Wagner’s anti-Semitism, as voiced in creations such as “Das Judenthum in der Musik,” an article was written under a false identity in 1850 and then again under his real name in 1869, and his increased focus on the supremacy of Germanic culture, were seen as formative to Nazism, and Hitler was an avid supporter of his songs and performances.

Arts and Crafts Movement

The Red House (1859), designed by William Morris and Philip Webb in Southeast London, was an early version of contemporary Gesamtkunstwerk. The home was also a notable representation of the Arts and Crafts movement, relying on Medieval Gothic style and employing conventional construction methods and materials.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones also contributed to the interior’s decoration and fitting, while Morris planned the outdoor landscape, all to achieve a singular aesthetic impact. The outcome was “more poetry than a home,” according to Rossetti.

The building became an influential example of Gesamtkunstwerk as a bustling center of the Arts and Crafts movement as well as the place where Morris launched his design studio.

Art Nouveau

Victor Horta’s Hôtel Tassel (1893), a private property created for the Tassel family, was one of the first instances of Art Nouveau. The style was popularized the same year by Paul Hankar’s Hankar House (1893).

The architecture, fittings, and furnishings of these residences were created to complement one another and create a comprehensive aesthetic impact.

According to art historian Kenneth Frampton, Van de Velde built a residence for himself that without a doubt was destined to illustrate the utmost synthesis of all the art forms, because besides incorporating the residence with all its interiors, along with the cutlery, Van de Velde tried to complete the total work of art through the cascading forms of the gowns that he designed for his wife.

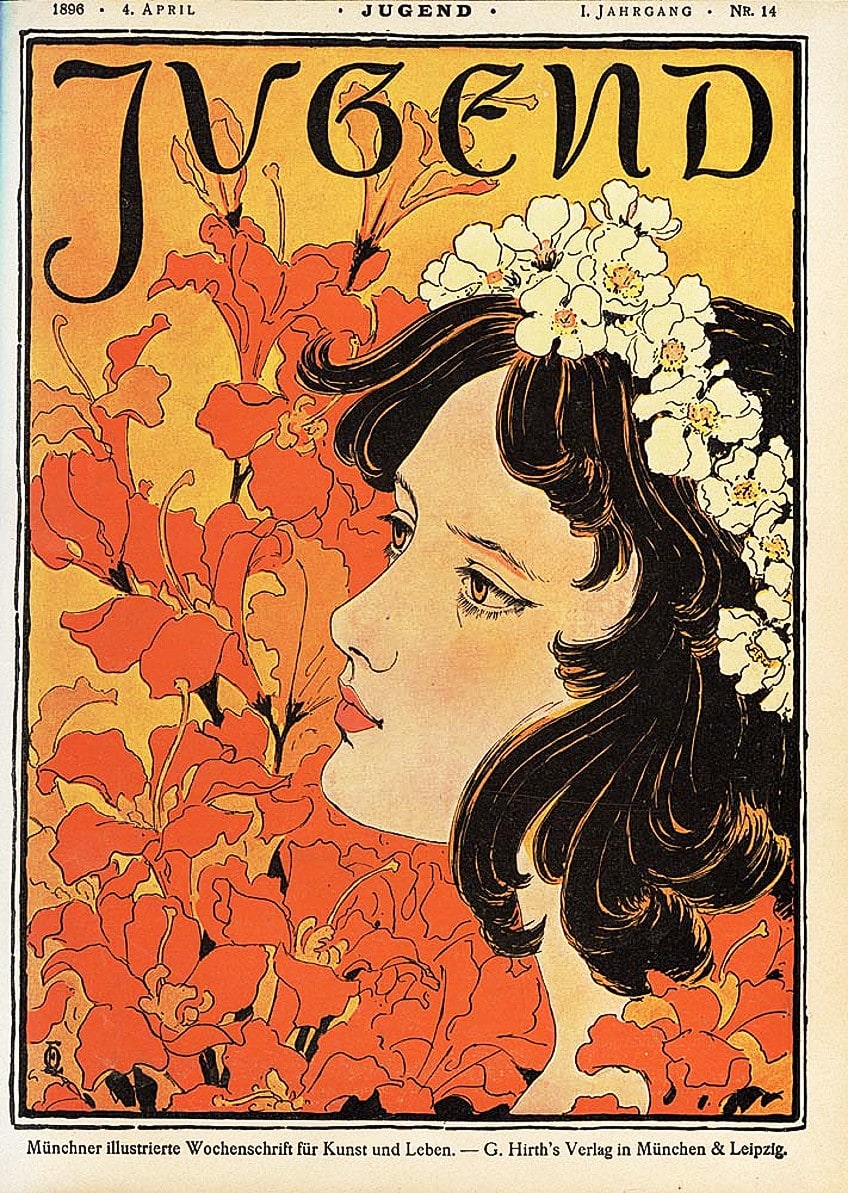

Jugendstil

Jugendstil, or “Art Nouveau” in German, began in 1896 in Munich with the work of Hermann Obrist. According to art historian Andrew Hickling, his “‘whiplash,’ a serpentine flurry of hairpin curves influenced by cyclamen stems, would become associated with fin-de-siècle style.”

The emphasis on beautiful lines, influenced by organic and occasionally geometric shapes, featured a new concept of style that, rejecting orthodox academic art, united all the arts into a Gesamtkunstwerk in the same way that Art Nouveau did.

Each artist’s residence was a meticulously crafted comprehensive work of art that also complemented the colony’s overall architectural impact and reflected its owner’s artistic preoccupations. For example, to represent the painter’s artistic activity, Olbrich’s façade for Hans Christiansen’s house was painted with brilliant colors and figurative ornamentation. Olbrich’s Ernst-Ludwig-Haus (1900 – 1901) served as the colony’s focal point, serving as a public reception room while also containing artist studios and workshop space.

The colony’s workshops embraced contemporary industrialization, manufacturing diverse goods commercially and pushing the concept that even the most basic dwelling might be a Gesamtkunstwerk, rejecting the hierarchical divide between fine and practical art and stressing craft.

The Vienna Secession

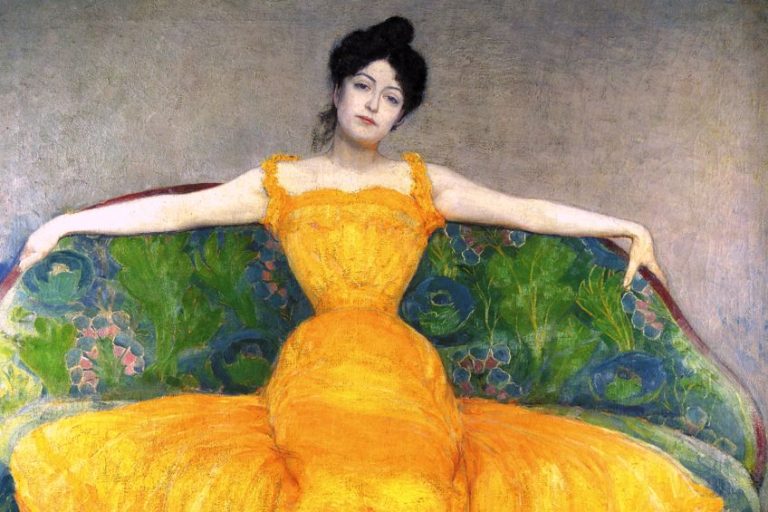

The Vienna Secession, in contrast to the conventional and academic order of the arts, promoted an international “total art” that combined the decorative arts with sculpture, painting, and architecture. Gustav Klimt established the movement in 1897.

The Secession Building (1897 – 1898) in Vienna, built by Olbrich and acting as the movement’s exhibition hall, was the movement’s earliest and most prominent project.

The design of the building, including the famed Beethoven Frieze (1901) created by Gustav Klimt and the characteristic façade features developed by Moser, resulted in a whole work of art that also served as the movement’s aesthetic credo. The Stoclet Palace in Brussels (1905 – 1911) was the movement’s crowning achievement.

The private mansion, designed by Josef Hoffman, with its dining hall holding murals by Gustav Klimt and utilizing expensive and rare materials, has been hailed as the sumptuous embodiment of Gesamtkunstwerk.

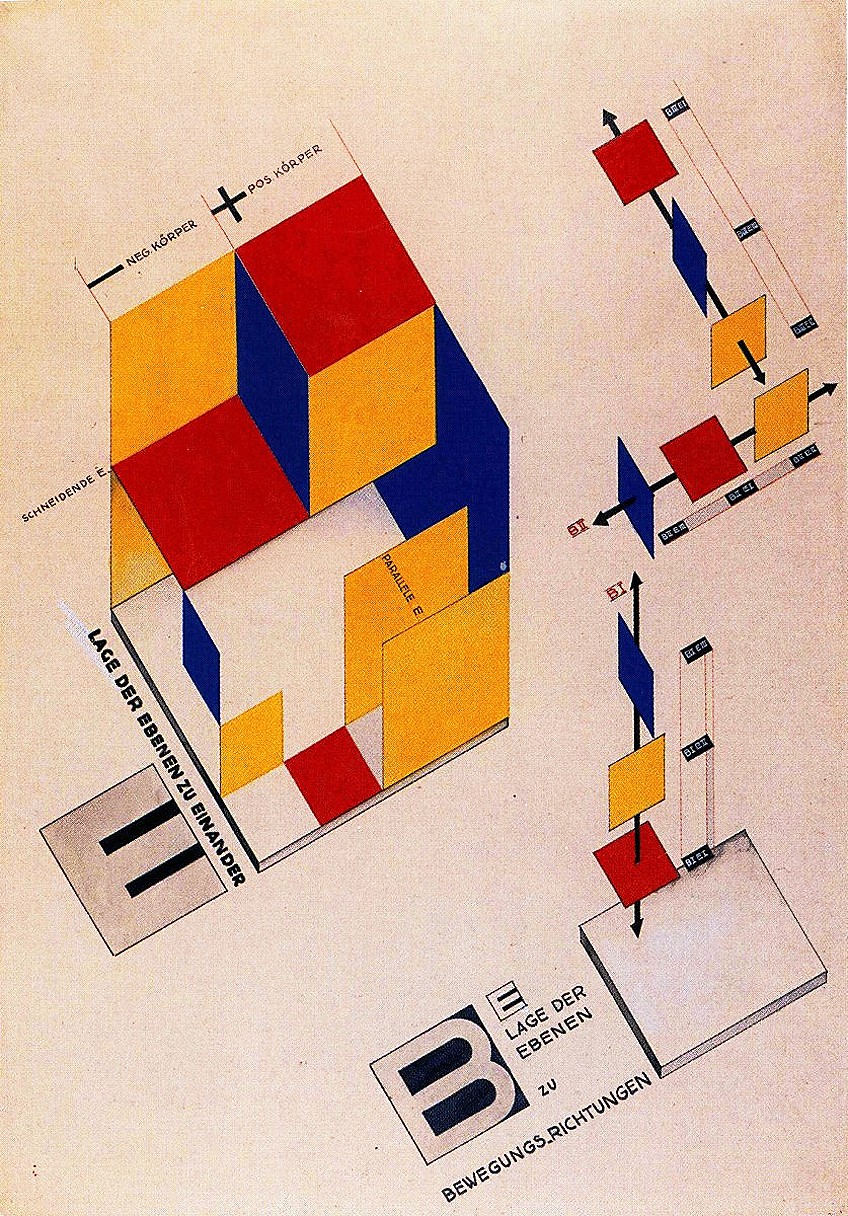

Bauhaus

Walter Gropius supported the notion of Gesamtkunstwerk while leading the Bauhaus, a school that stressed rigorous instruction in the trades as well as the fine arts. In 1919, he declared the “ubiquitously great, everlasting spiritual-religious notion, which must find its crystalline form in a grand Gesamtkunstwerk” in his Manifesto.

Redefining the word from “total work of art” to “Total Design,” he thought it extended to all parts of contemporary living, from designing a manufacturing plant to urban planning to a private dwelling, and to all of its features ranging from desktops to lighting, teapots, and cutlery.

Notable Examples of Gesamtkunstwerk

Gesamtkunstwerk concepts were frequently connected with the broader goals and beliefs of the art groups that embraced it, and the union of arts and artists that generated Gesamtkunstwerk was considered as having the ability to build a more equal and, eventually, utopian society.

Some kinds of Gesamtkunstwerk were closely associated with nationalism. The Arts & Crafts Movement, for example, encouraged traditional English workmanship.

More sadly, some of Wagner’s thoughts and work may be considered as establishing the basis of Nazi ideology, and his ideals of musical traditionalism served to legitimize the new party. Many artists abandoned the notion of Gesamtkunstwerk after WWII as a result of this relationship.

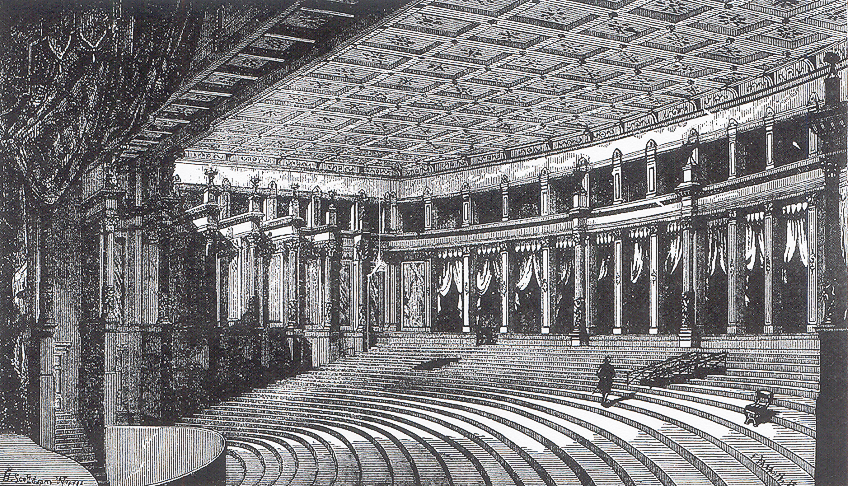

Bayreuth Festival Theater (1876)

| Date Completed | 1876 |

| Architect | Richard Wagner |

| Style | Gesamtkunstwerk |

| Location | Bayreuth, Bavaria, Germany |

The Bayreuth Theater’s façade recalls late-nineteenth-century architectural trends, with pillars and geometric shapes of light-colored stone surrounding the main entrance. It stands on a little hill above a garden set out in a geometric style that mimics the décor on the exterior, imposing and recalling the look of a classical temple.

Richard Wagner designed the theatre as a location for his opera cycles to be performed during the yearly Bayreuth Festival, formally known as the Richard-Wagner-Festspielhaus, which is still in operation today. As a result, the theater and its acts embodied his idea of Gesamtkunstwerk, with each part working together to produce a holistic aesthetic experience.

The foundation stone for the structure was laid on Wagner’s birthday in 1872, and the theatre debuted in 1876 with Der Ring des Nibelungen, Wagner’s cycle of four operas. Wagner pioneered a unique design that included continental seating (a seating configuration without a center aisle) and a sunken orchestral pit to connect the opera presentation with the architecture.

To increase acoustics, he predominantly employed wood for the inside. Every seat had an excellent view of the stage thanks to the continental seating, which was organized in a single wedge. The double proscenium created a “mystic chasm” between the stage and the audience, heightening the surreal and legendary nature of Wagner’s operas.

At the same moment, the orchestra pit, which was buried beneath the stage, was unseen, allowing the audience to concentrate solely on the opera. Following that, several theaters implemented these features.

Hotel Tassel (1893)

| Date Completed | 1893 |

| Architect | Victor Horta |

| Style | Gesamtkunstwerk, Art Nouveau |

| Location | Brussels |

This townhouse was groundbreaking in its architectural techniques and fluid, open design, and is regarded as one of the earliest full instances of an Art Nouveau structure. Horta emphasized organic, curved lines with modern materials, mainly steel and glass, to create a façade that flowed both horizontally and vertically. He innovated the use of thin iron columns rather than traditional stone columns, which allowed for huge windows. Horta also designed the inside, giving the building an open floor plan and stressing natural light, resulting in a completely integrated, light-filled room.

Details like the light fittings, glass panels, doorknobs, and stair railings replicated sinuous plant-like shapes, defining both the overall Art Nouveau style as well as providing a coherent decorative and architectural scheme across the house./strong>

This structure was listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2000 and is said to be “among of the most notable pioneering works of architecture of the late 19th century. The open plan, light dispersion, and dazzling linking of the curving lines of ornamentation with the framework of the building characterize the stylistic revolution represented by these works.”

Ernst-Ludwig-Haus (1901)

| Date Completed | 1901 |

| Architect | Joseph Maria Olbrich |

| Style | Gesamtkunstwerk |

| Location | Darmstadt, Germany |

This structure was the focus of the Darmstadt Artists’ Colony (established in 1899) and functioned as an artist’s studio. It was a significant instance of Gesamtkunstwerk within the Jugendstil style. Olbrich was a key member of the Vienna Secession and had created the famous Secession exhibit building three years prior when he was commissioned by Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig to develop the colony. Olbrich took use of the chance to design a structure that combined architecture, sculpture, and ornamental elements.

The white walls and beautiful gold frieze around the door show the influence of the Vienna Secession. The huge windows highlight the building’s practicality, while the colossal male and female sculptures by artist Ludwig Habich on either side of the stairwell attest to its function, expressing power and beauty.

Imperial Hotel (1923)

| Date Completed | 1923 |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Style | Gesamtkunstwerk |

| Location | Meiji Mura, Near Nagoya, Japan |

The Imperial Hotel’s façade combines Wright’s Prairie Style with the Mayan Revival style, as well as Japanese elements. A reflecting pool at the entryway, fronted by two enormous stone figures, reminded Mayan plazas. As the guest entered the structure through a low and gloomy corridor before climbing the stairs into the vastness of the central lobby, the pattern persisted throughout, as evident in a couple of stone pillars and the temple-like entrance door.

Wright meticulously created all of the hotel’s parts and fittings, most notably towering columns with incised surfaces etched with patterned perforations to produce light, earning them the moniker “pillars of light.”

The columns’ designs echoed Mayan hieroglyphs, but their light-filled presence resembled the Japanese drifting lanterns that influenced Wright. Wright was commissioned by the Japanese government to design a hotel building that would appeal to Westerners. He masterfully engineered the skyscraper, which was built in an earthquake-prone location, utilizing large concrete piles and an H-shaped layout.

That wraps up our look at Gesamtkunstwerk. Although the concept fell out of favor during the postmodern era, it is nevertheless used to describe multimedia installations and works today. Gesamtkunstwerk survives most notably in architecture, where all components of the structure; internal, exterior, and furnishings were designed to complement one another, and this influence can be seen in the creative practices of numerous groups.

Take a look at our Gesamtkunstwerk architecture webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Gesamtkunstwerk?

The German Gesamtkunstwerk definition can be roughly translated to mean a total work of art, as it refers to an artwork, concept, or creative approach in which various art disciplines are combined to form a single cohesive whole. The composer Richard Wagner popularized the notion, advocating for the ultimate art of the future, in which no rich talent of the many arts would go untapped in the Gesamtkunstwerk of the coming years.

Which Art Forms Fall Under Gesamtkunstwerk?

The term Gesamtkunstwerk, meaning total work of art, is most commonly associated with architecture, in which all components of the design, including the interior, outside, and furnishings, were constructed to complement one another. This impact may be observed in movements such as Arts and Crafts, Art Deco, Art Nouveau, Jugendstil, Bauhaus, Vienna Secession, and De Stijl’s aesthetic approach. Gesamtkunstwerk concepts were frequently connected with the larger ideals and beliefs of the art groups that embraced it, and the union of arts and artists that generated Gesamtkunstwerk was seen as having the ability to build a more equal and, eventually, utopian society.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Gesamtkunstwerk – Explore Gesamtkunstwerk in Architecture and Art.” Art in Context. May 9, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/gesamtkunstwerk/

Meyer, I. (2022, 9 May). Gesamtkunstwerk – Explore Gesamtkunstwerk in Architecture and Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/gesamtkunstwerk/

Meyer, Isabella. “Gesamtkunstwerk – Explore Gesamtkunstwerk in Architecture and Art.” Art in Context, May 9, 2022. https://artincontext.org/gesamtkunstwerk/.