Dante Gabriel Rossetti – Studying the Famous Pre-Raphaelite Artist

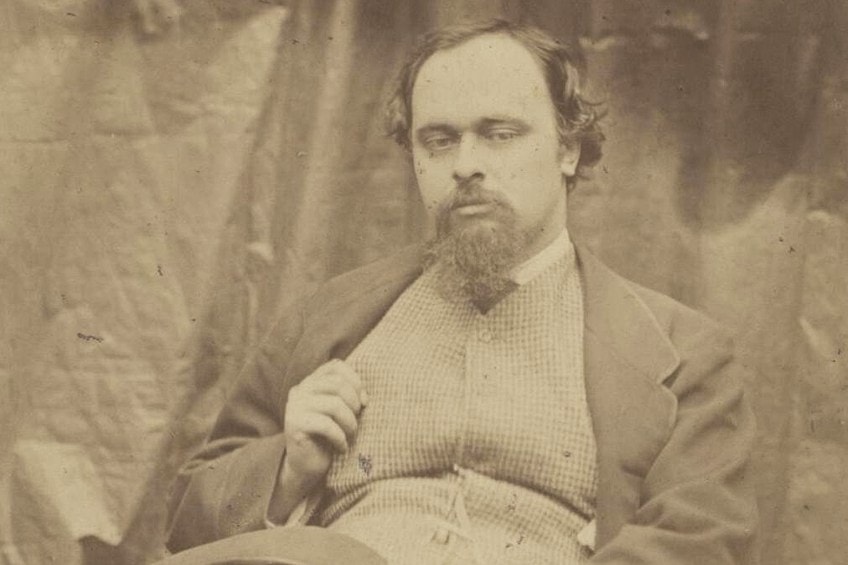

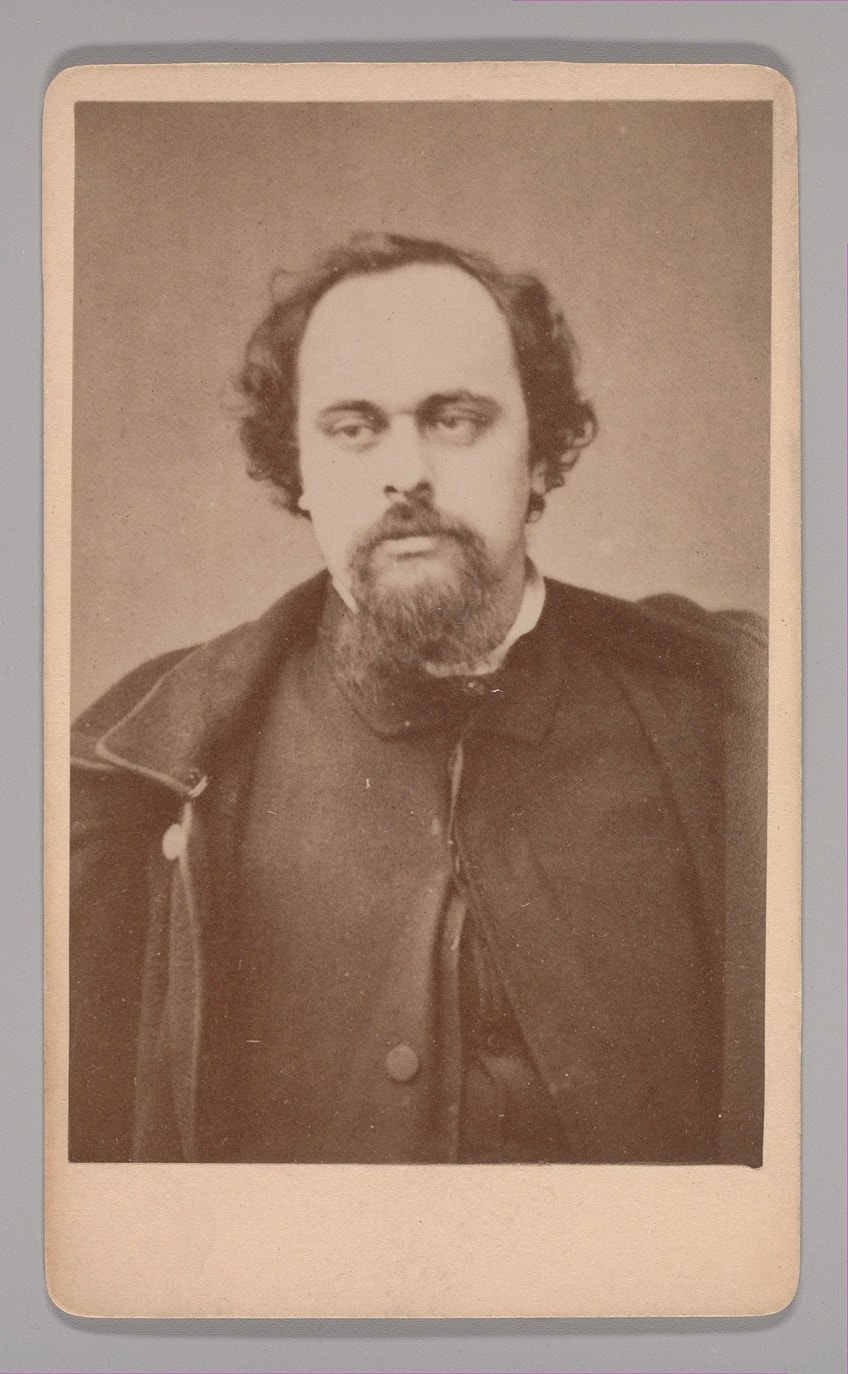

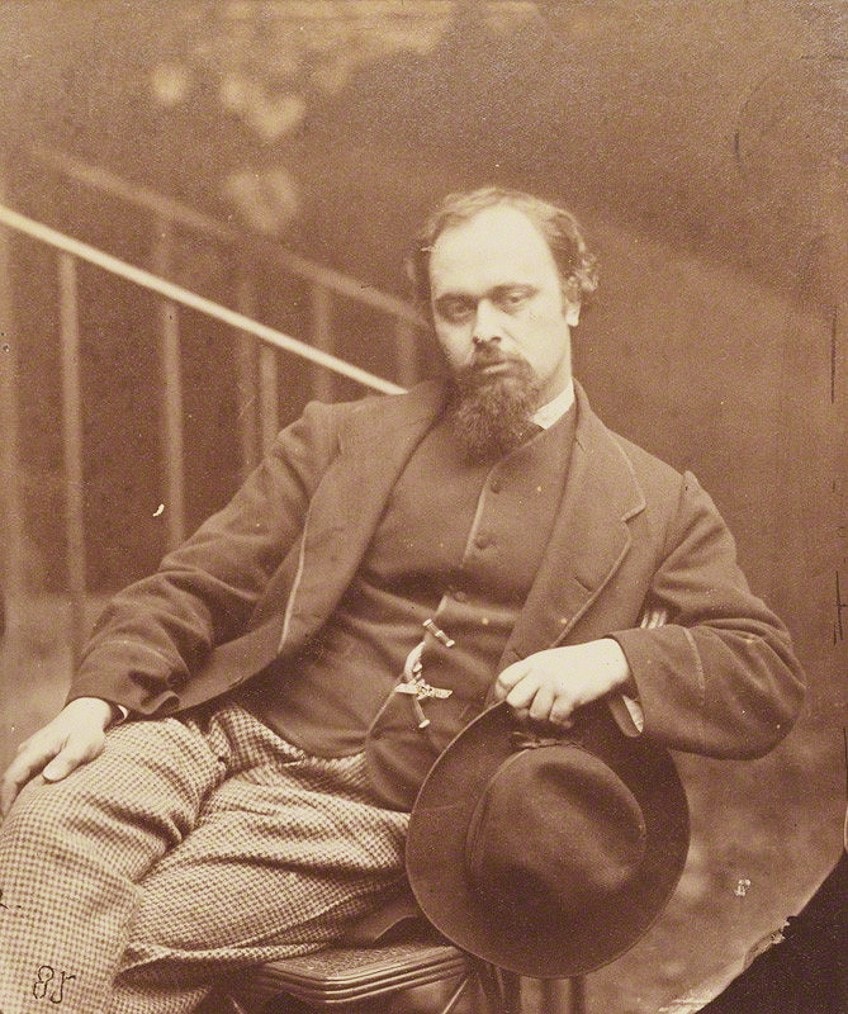

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was a poet and painter from England who co-founded the pre-Raphaelite movement. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s paintings reflected the movement’s desire to create artworks with a strong moral message. In this article, we will take a look at Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s biography and important artworks.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Biography

| Nationality | English |

| Date of Birth | 12 May 1828 |

| Date of Death | 9 April 1882 |

| Place of Birth | London, England |

The pre-Raphaelite movement which Rossetti had co-founded sought to find inspiration in the religious artworks of the Medieval period and eschewed what they considered to be “decadent” artistic indulgences. It was a movement that held very rigid beliefs about the purity of art and life, and it was something that the artist would eventually grow bored with.

Although the subject matter of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s paintings was predominantly religious, he was most known as a portrait painter.

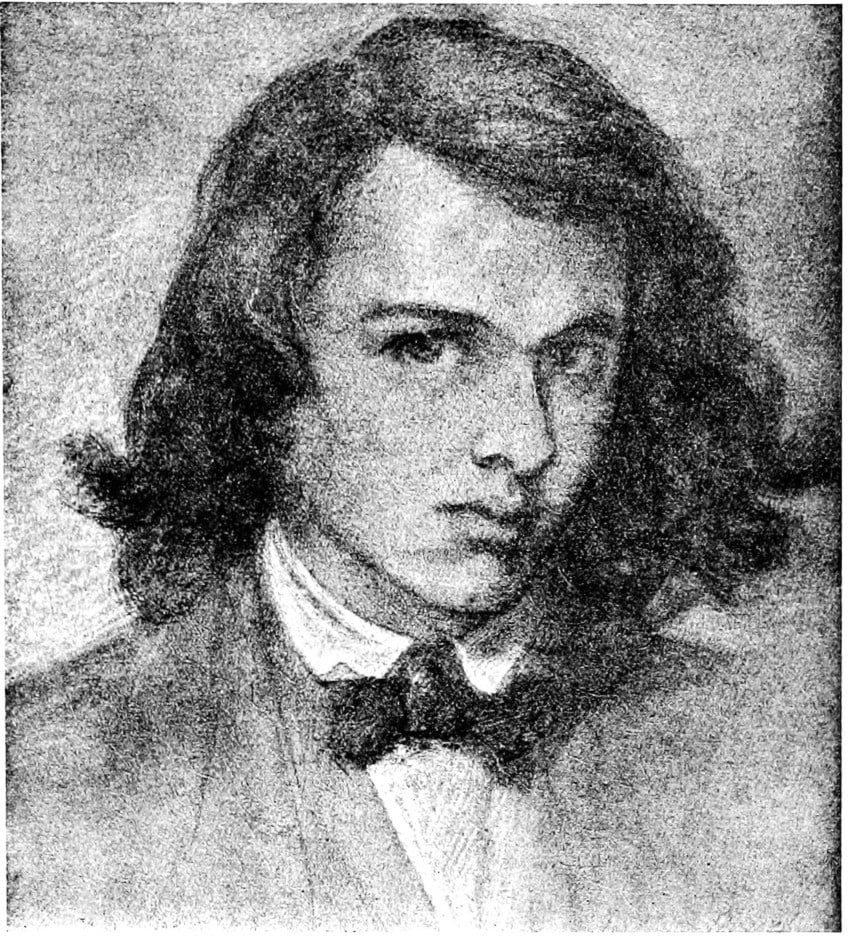

Early Life

Following a basic junior education at King’s College, Rossetti deliberated between poetry and art as a career. He attended Sass’s, an old art workshop in downtown London, when he was approximately 14 years old, and then went to the Royal Academy schools in 1845. Simultaneously, he devoured romance and poetry, J. W. von Goethe, William Shakespeare, Sir Walter Scott, and Gothic horror stories. He was captivated by the works of American author Edgar Allan Poe.

He discovered the works of William Blake in 1847 when he bought a collection containing William Blake’s drawings and essays in poetry and verse.

By the age of 20, Rossetti had already completed a number of adaptations of Italian poets and had written some original poems, but he was also frequently in painters’ workshops and was, for a brief period, an unofficial student of the artist Ford Madox Brown. He shared some of Brown’s passion for the German “pre-Raphaelites,” the rigorous Nazarenes who attempted to restore the pre-Renaissance simplicity of style and purpose in German painting. For them, it felt like the next natural step was to start something similar in England.

The English pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in 1848, mostly due to the work of Rossetti. They wanted to create works that were true to nature by painting outdoors and focusing on the small details. This was specifically the intention of John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, two of the other founding members of the movement.

Rossetti was responsible for broadening the interests of the group to include social idealism and poetry in their works, and for bringing the idea of looking to a romanticized version of the Medieval past for inspiration.

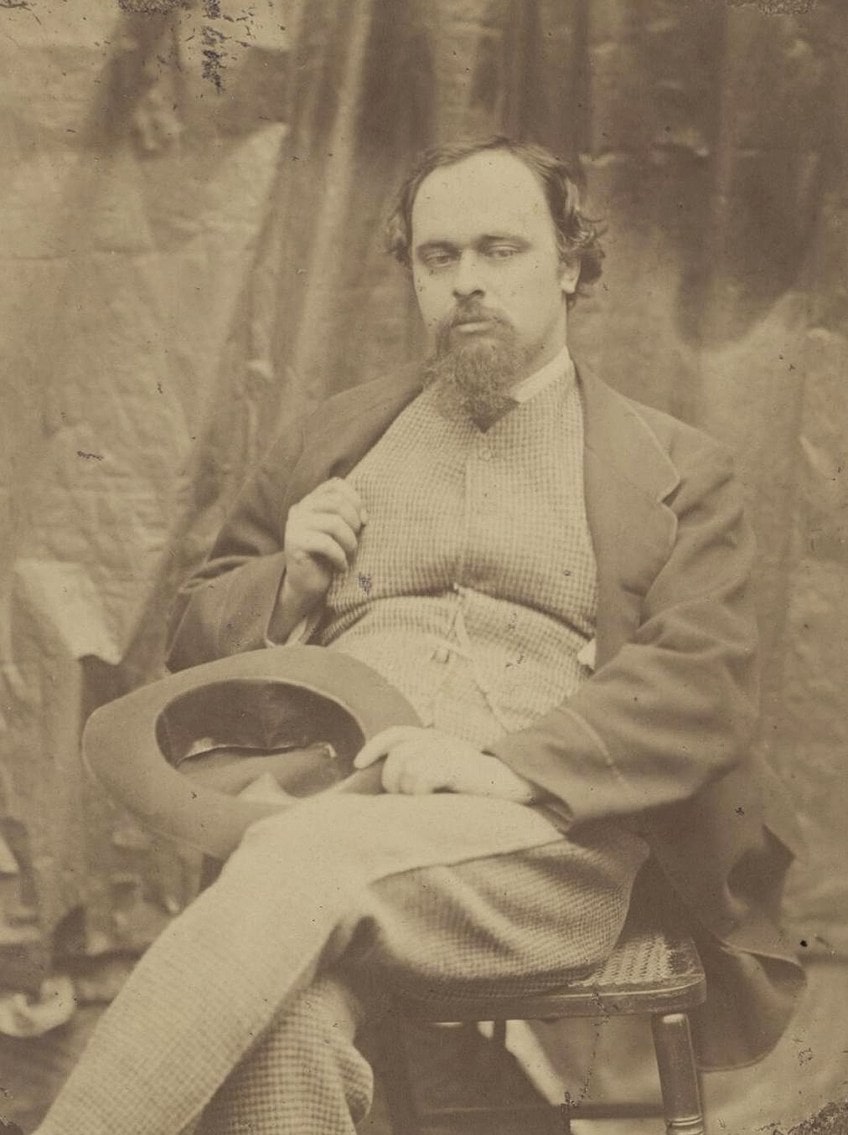

For Rossetti, the 1850s were momentous years. They started with the entrance of the lovely Elizabeth Siddal into the pre-Raphaelite circle, who acted as a subject for the entire group initially but quickly became connected to Rossetti exclusively and the two wedded in 1860. Many portrait sketches demonstrate his feelings for her.

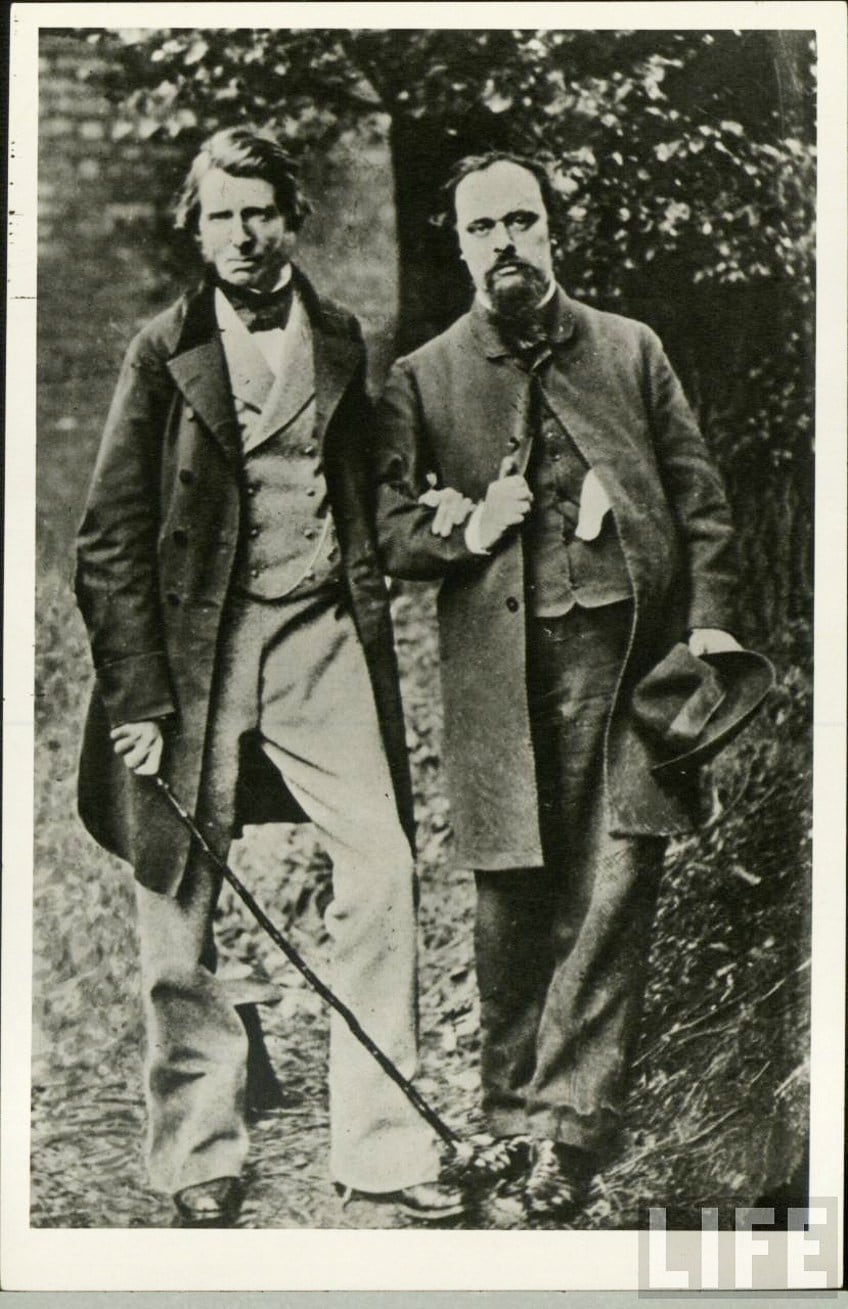

He found a powerful yet demanding patron in 1854 in the form of John Ruskin, an art critic.

By then, the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had disbanded, fractured by its members’ varying interests and dispositions. However, Rossetti’s captivating personality sparked a new surge of interest. In 1856, he met William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, and with these two young students, he launched the pre-Raphaelite school into its second phase. The romantic excitement for a mythical past, rather than the reality of “true to nature,” was the driving force behind this new direction, as was the aim to improve the practical arts of design.

Rossetti’s impact extended not just to easel paintings depicting Arthurian mythology, but also to other realms of art.

Later Years

From 1860 on, challenges were a continuous feature of Rossetti’s troubled existence. His marriage to Elizabeth Siddal was marred by her continuous illness and ended tragically in 1862 when she died of a laudanum overdose. Grief drove him to bury the only full manuscript of his poetry alongside her. The allegorical Beata Beatrix, produced in 1863 and currently housed in the Tate Gallery, demonstrates that he compared his affection for his wife to Dante’s magical and ideal love for Beatrice. Rossetti’s life and work were forever altered. He relocated from London’s Blackfriars district to Chelsea.

The influence of new friends – Algernon Charles Swinburne, and James McNeill Whistler – led to a more aesthetic and sensual approach to painting.

Literary subjects gave place to images of everyday beauty, such as his lover, Fanny Cornforth, who was beautifully dressed and depicted with a mastery of oil he had not before demonstrated. These paintings’ opulent colors and rhythmic patterns accentuate the impression of their leisurely, sensual female models, all of whom have a particular pre-Raphaelite facial shape. The paintings were well received by collectors, and Rossetti became wealthy enough to hire studio helpers to manufacture duplicates and reproductions. He also collected antiques and had a collection of birds and animals in his big Chelsea garden.

Rossetti had achieved some success with his translated publications in 1861, and by the end of the 1860s, his attention had returned to poetry. He resumed writing new poetry and planned the retrieval of the manuscript poetry lying in Highgate Cemetery with his wife. The exhumation, carried out in 1869 by his eccentric business partner, Charles Augustus Howell, obviously troubled the superstitious Rossetti. These poems were first published in 1870.

The poems were favorably praised until Robert Buchanan launched a misguided, violent campaign against Rossetti. Rossetti answered calmly in “The Stealthy School of Criticism” (1871), but the assault, mixed with regret and the quantity of chloral and alcohol he was now taking for insomnia, led to the deterioration of his health in 1872.

He recovered enough to write and paint again, but his life in Chelsea became that of a hermit. He spent a lot of time at Kelmscott Manor, which he co-owned with William Morris until 1874. At the time, his beautifully romanticized images of Jane Morris represented a return to his more mystical and poetic manner. Rossetti spent the early 1880s working on a reproduction of an early painting and a modified edition of poems. Rossetti returned from a visit to Keswick in worse condition than before, and he passed away the following spring.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Paintings

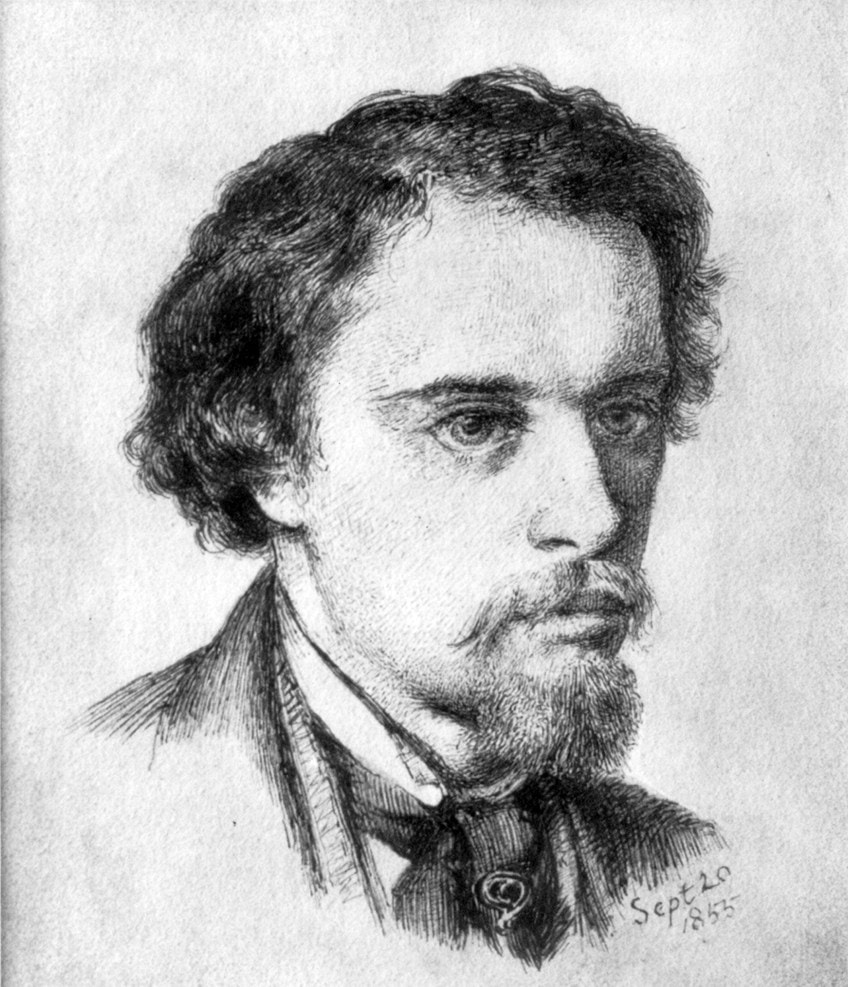

Rossetti is well-known for his portraiture. His chosen topic was religious in subject matter, but as he developed as an artist, his works became progressively divisive owing to his tendency for depicting sacred symbols using lovers and relatives.

His hedonistic lifestyle, while denounced by many of his contemporaries, gave his artwork sensual energy and, it must be noted, significant uniqueness.

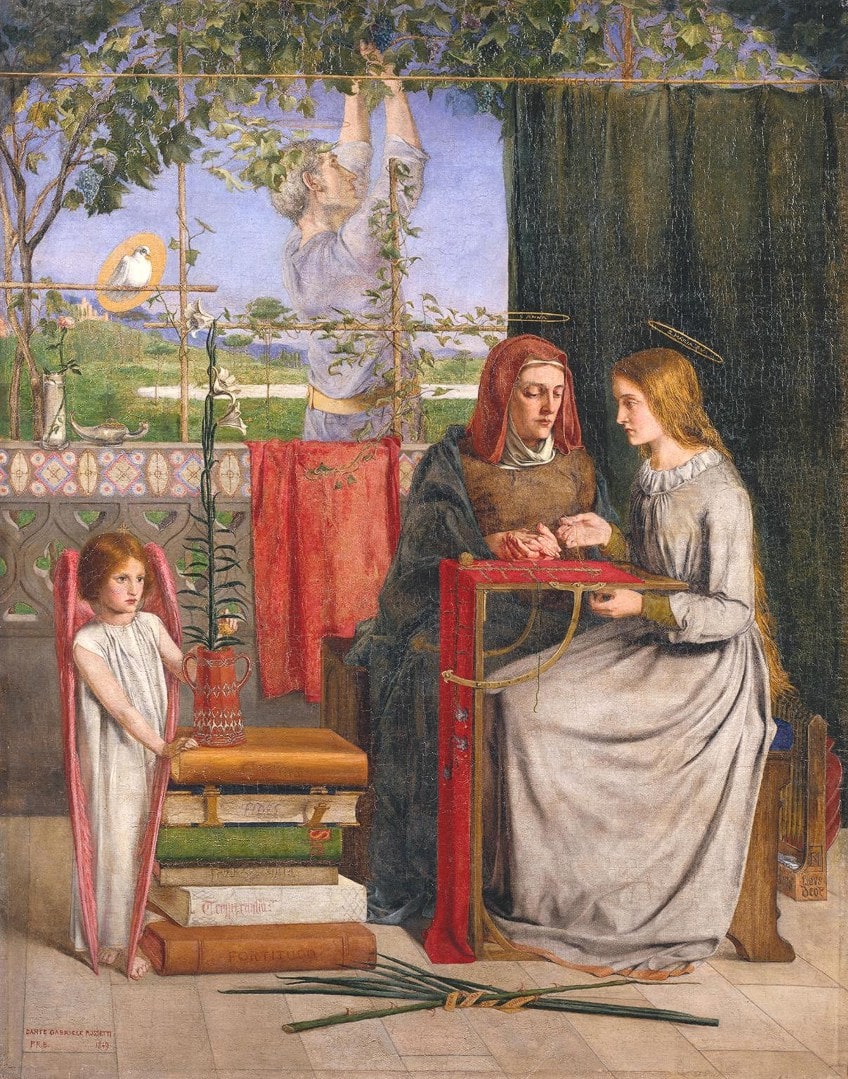

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849)

| Artist | Dante Gabriel Rossetti |

| Date Completed | 1849 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom |

The Virgin Mary’s childhood was a popular subject in medieval religious artwork. Rossetti, on the other hand, preferred to imbue his tale with bright colors and metaphorical meanings rather than represent a literal scriptural scenario. The relevance of the child Mary stitching a lily has been discussed since it alludes to the pre-Raphaelites’ own devotion to nature. It also elevates needlework and the ornamental arts in general, elevating them from a minor skill to a significant, even semi-spiritual activity. Another unusual aspect of the artwork was its utilization of relatives as subjects for the religious icons by Rossetti.

The Virgin Mary was modeled after his sister Christina, Saint Anne after his mother, and Joachim after an elderly household servant.

Using commonplace subjects for holy figures was unusual and bold, and just a few years later, John Everett Millais received major criticism for using relatives as models in his work. Rossetti took extraordinary care with the artwork’s frame, demonstrating an early interest in adorning and aesthetically affecting every component of a finished piece. For him, this also included enhancing the artwork with poetry, and he composed two sonnets to be read with the picture, one written on the frame and the other in the exhibit brochure. His purpose was to produce a dual work of art that blurred the lines between visual and literary categories.

Ecce Ancilla Domini (1850)

| Artist | Dante Gabriel Rossetti |

| Date Completed | 1850 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom |

Rossetti opted to resume his theme of religious subjects a year after his “reworking” of the Virgin Mary’s infancy by portraying the Annunciation; the time when the Angel Gabriel visited Mary delivering the word of her miraculous pregnancy. Rossetti establishes a symbolic continuity by depicting the Virgin Mary amid lilies, which were frequently employed as a sign of purity in Medieval and Italian Renaissance art.

In this case, Gabriel gives Mary a flower as a sign of her everlasting innocence and purity. Gabriel and Mary are both dressed in virginal white garments with golden haloes and accented with the beautiful royal, celestial blue that is traditionally identified with Mary. Her bedroom has a deep crimson panel with a floral pattern.

When the artwork was shown at the National Institution in 1850, it drew scathing condemnation for Rossetti’s daring re-imagining of the Annunciation. Instead of bowing for prayer, Mary is represented on her crumpled bed, dressed in a long, wrinkled white nightgown characteristic of a newlywed wife.

Gabriel, on his part, is depicted without wings and dressed in a flowing white garment that exposes his bare hip and thigh. Both beings appear ethereal while simultaneously being made of flesh and blood. A reviewer was taken aback by Rossetti’s irreverence for typical Annunciation scenes, describing it as “a piece obviously pushed by the painter into the face of the spectator with the arrogance of a teacher rather than the humility of a hopeful and earnest quest towards greatness.”

Rossetti never showed the picture again in public, and by the 1850s, he had shifted away from complex biblical settings and toward feminine portraiture.

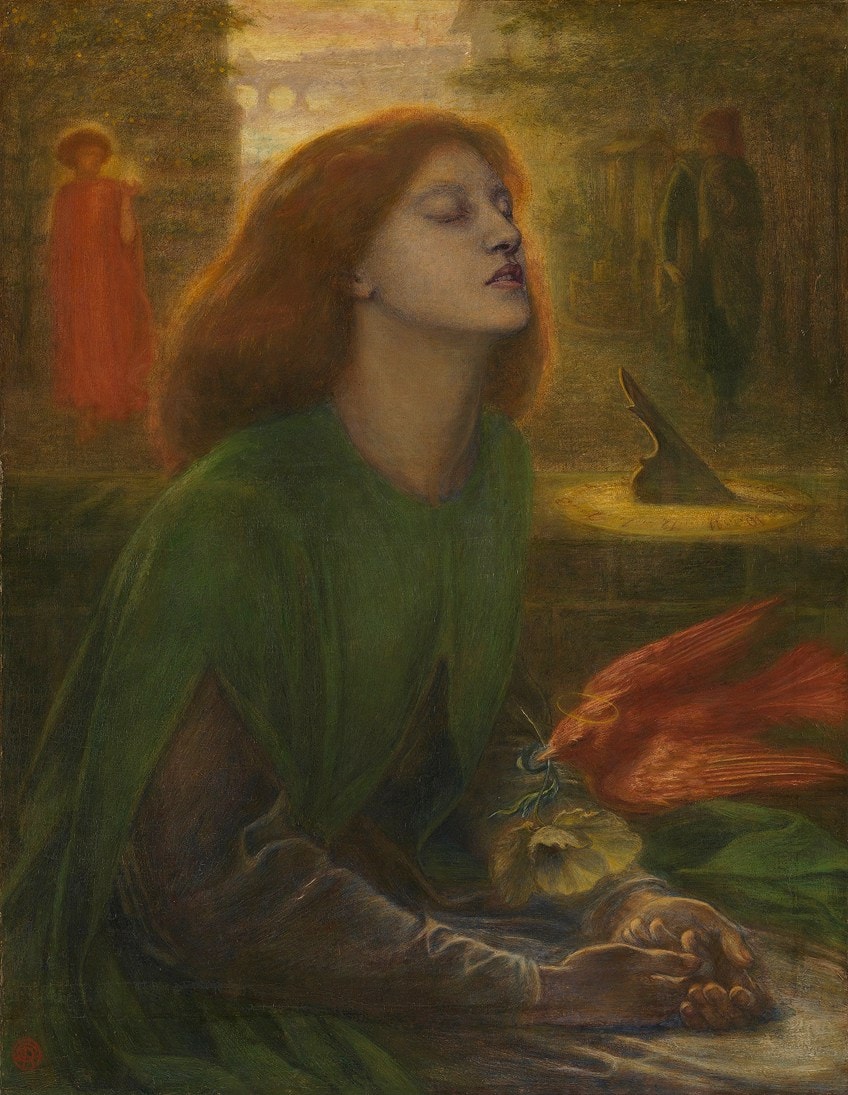

Beata Beatrix (c. 1864-1870)

| Artist | Dante Gabriel Rossetti |

| Date Completed | c. 1864-1870 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom |

There is a narrative about Rossetti that relates how, shortly after his beloved Lizzie died, the artist felt compelled to produce a memorial picture in her honor. To some extent, this is correct, but Rossetti actually transformed the elements of an incomplete picture into a new piece that became his wife’s eulogy.

Rossetti chose to show an idealized, exquisitely melancholy image of Elizabeth, presumably out of remorse, rather than the reality of her addictions and the negatives of their turbulent relationship.

Elizabeth is depicted in a condition of unexpected spiritual transfiguration, rather than at the time of her death. She is shown as an angelic figure kneeling in pleasure, as though poised to accept communion. Her eyes are closed, her head is inclined up, and she is bathed in a beautiful golden glow. The remainder of the color palette, on the other hand, is subdued, and Lizzie’s dress’s gray and green represent the hues of hope and sadness, as well as love and life.

The red dove, however, represents a deeper meaning in the image. The red dove, a symbol of the Holy Spirit descending to take Elizabeth to the Afterlife, lands on her and places a poppy in her uplifted hands. This feature honors the beauty of the Poppy, the flower that caused her death due to her Laudanum addiction. The dove also had a personal resonance for Rossetti, as “Dove” was his nickname for Elizabeth.

Elsewhere, Dante confronts an obscure red-cloaked woman who symbolizes Love and clutches a burning candle, as the light of Beatrice’s life begins to wane.

Proserpine (1874)

| Artist | Dante Gabriel Rossetti |

| Date Completed | 1874 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom |

By 1874, Rossetti was suffering from a mental collapse, aggravated by a dependency on alcohol. Rossetti had grown rather obsessed with his lover Jane Morris, the only one he never really acquired as a result of her miserable marriage to William Morris. Nevertheless, during the 1870s, Rossetti created several portraits of Jane. She is the epitome of grace, with her, lush raven hair, arched neck, and flowing blue silk gown. Despite her tranquil beauty, her demeanor is remote and she appears rather lonely.

Although this Rossetti painting is signed with the date 1874, it was repainted and redone no less than seven times over 10 years, indicating Rossetti’s preoccupation with Morris.

In this piece, she is reimagined as the Goddess Proserpine, whose story paralleled the pair’s own. According to the tale, Proserpine must journey to the netherworld and abandon her soul mate, Adonis. She unintentionally swallows pomegranate seeds while in the Underworld, compelling her to dwell there with Hades for half of the year. She could only return to Adonis in the sunlight of the world above during the six summer months. Jane, like Proserpine, felt bound by her husband, but during the summer season, when William Morris was remodeling their house, she and Rossetti resided at Kelmscott Manor, where they were able to continue their love affair.

“Proserpine” is often regarded as Rossetti’s final major work, produced right before he succumbed to mental and physical disease.

Recommended Reading

Now that you have learned a bit about Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s biography, perhaps you would like to learn some more. There are several books that go further into Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s paintings and life that might interest you. Check out these books below to learn even more!

The Blessed Damozel (1850) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

This is one of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s most renowned poems, as well as the title of his artwork that depicts the subject. Damozel is described in the poem as seeing her beloved from heaven and longing for their reunion in paradise. Dante’s amazing use of language perfectly conveyed the love and agony of a woman locked in heaven and a man stuck on Earth.

Hand and Soul (1869) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Despite its form as a short story or prose poem, Rossetti saw this work as a “very serious declaration of creative orthodoxy” in which “the only legitimate creations are those that represent the spirit of the artist.” As such, it functions as a form of declaration for the pre-Raphaelite movement. This Kindle reprint comes from William Morris’s Kelmscott Press edition, which is a piece of beauty in and of itself, and it keeps exquisite typography in red and black.

- Quoted by Rossetti as a “very serious manifesto of artistic dogma”

- A kind of manifesto for the pre-Raphaelite movement

- A reproduction from William Morris’ Kelmscott Press edition

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood founder, focused on a time well before the High Renaissance. He was influenced by the clarity and mystery of medieval and religious stories observed in 15th-century Florentine and Sienese artwork. Rossetti had a lifelong ambition to become a poet in the mold of his heroes, Byron, Dante, and Keats, and had hoped to retire from painting in his later years. Today, Rossetti’s art is regularly reproduced and displayed. The pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood is today regarded as the first really contemporary British painters, according to critical interpretations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Dante Gabriel Rossetti?

Rossetti was one of the founders of the pre-Raphaelite movement. However, he eventually grew tired of their rigid rules regarding art. He was most known as a portrait artist.

What Was the Pre-Raphaelite Movement?

The pre-Raphaelites thought that the art of the era was too decadent. They wanted art to represent nature and purity. They looked back towards the Medieval period as an example.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Dante Gabriel Rossetti – Studying the Famous Pre-Raphaelite Artist.” Art in Context. September 21, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/dante-gabriel-rossetti/

Meyer, I. (2022, 21 September). Dante Gabriel Rossetti – Studying the Famous Pre-Raphaelite Artist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/dante-gabriel-rossetti/

Meyer, Isabella. “Dante Gabriel Rossetti – Studying the Famous Pre-Raphaelite Artist.” Art in Context, September 21, 2022. https://artincontext.org/dante-gabriel-rossetti/.