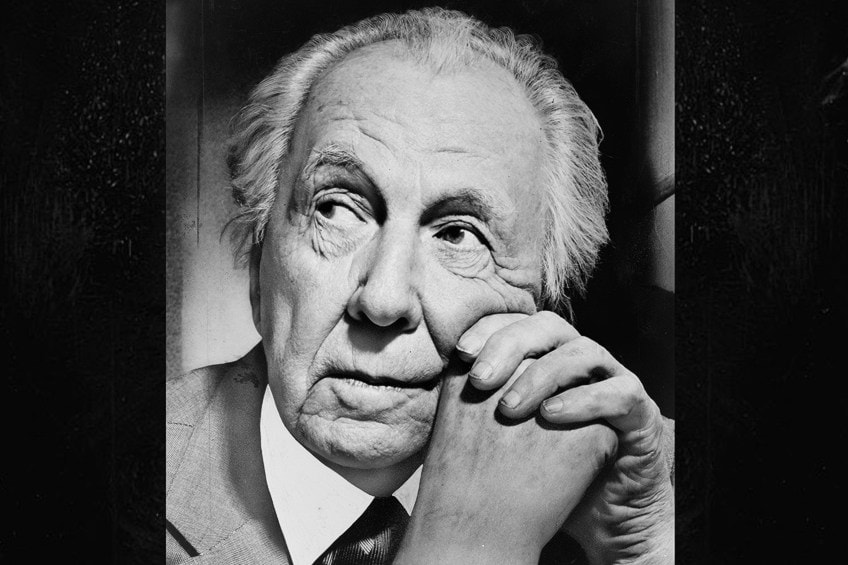

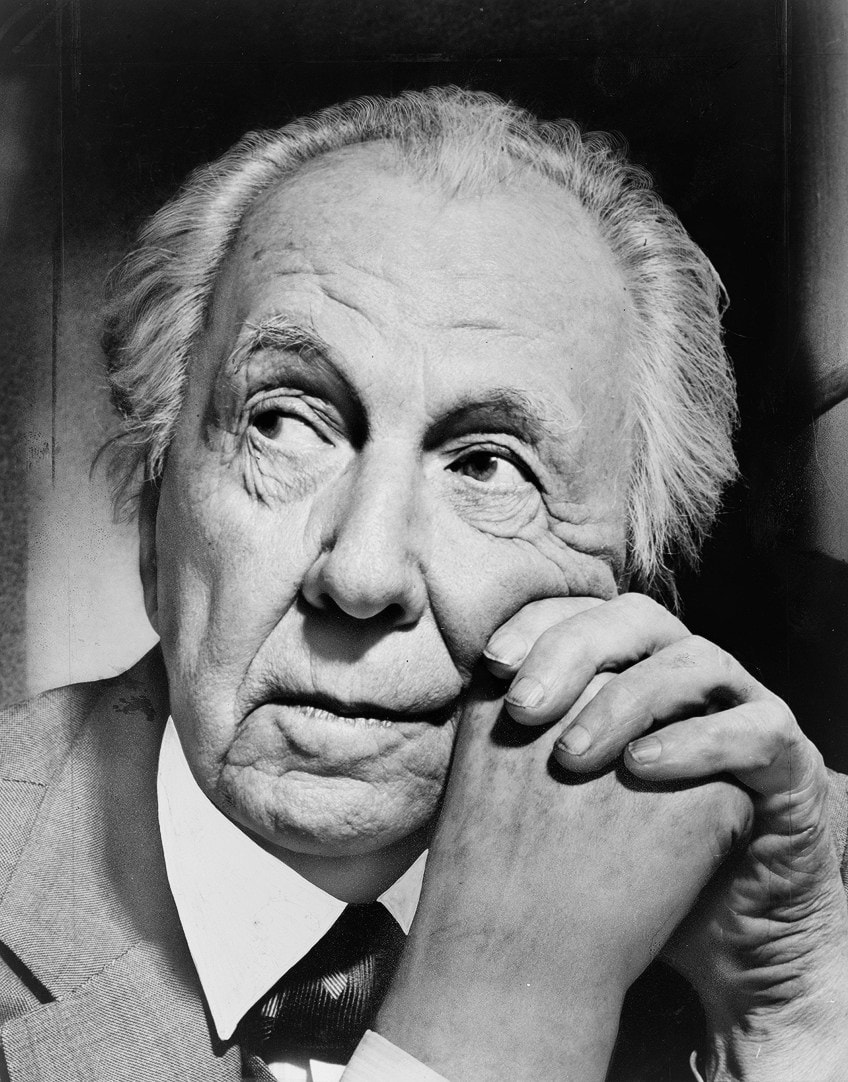

Frank Lloyd Wright – Who Was Frank Lloyd Wright, the Architect?

Who was Frank Lloyd Wright? Frank Lloyd Wright was a renowned architect known for his famous architectural houses. How many Frank Lloyd Wright houses are there, though? Over the course of a 70-year career, he produced designs for more than 1,000 buildings of almost every form imaginable, of which 532 of Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs were actually constructed. Today will discuss all there is to know about Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture and life.

Who Was Frank Lloyd Wright?

The principal philosophy of Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs, known as “organic architecture,” in essence encouraged the development of structures that emanated unity with their specific surroundings, complementing rather than intruding on them.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture emphasized minimalism and utility in arrangement and design, as well as the open exposure of the inherent qualities of components appropriate for their function.

Unlike the architects of the International Style, he did not shy away from adornment, yet drew inspiration straight from nature. But before we go into any further details about Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings, let us take a look at his biography. Where was Frank Lloyd Wright born and when did Frank Lloyd Wright die? We will explore the answers to these questions and more below.

A Brief Biography of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Life

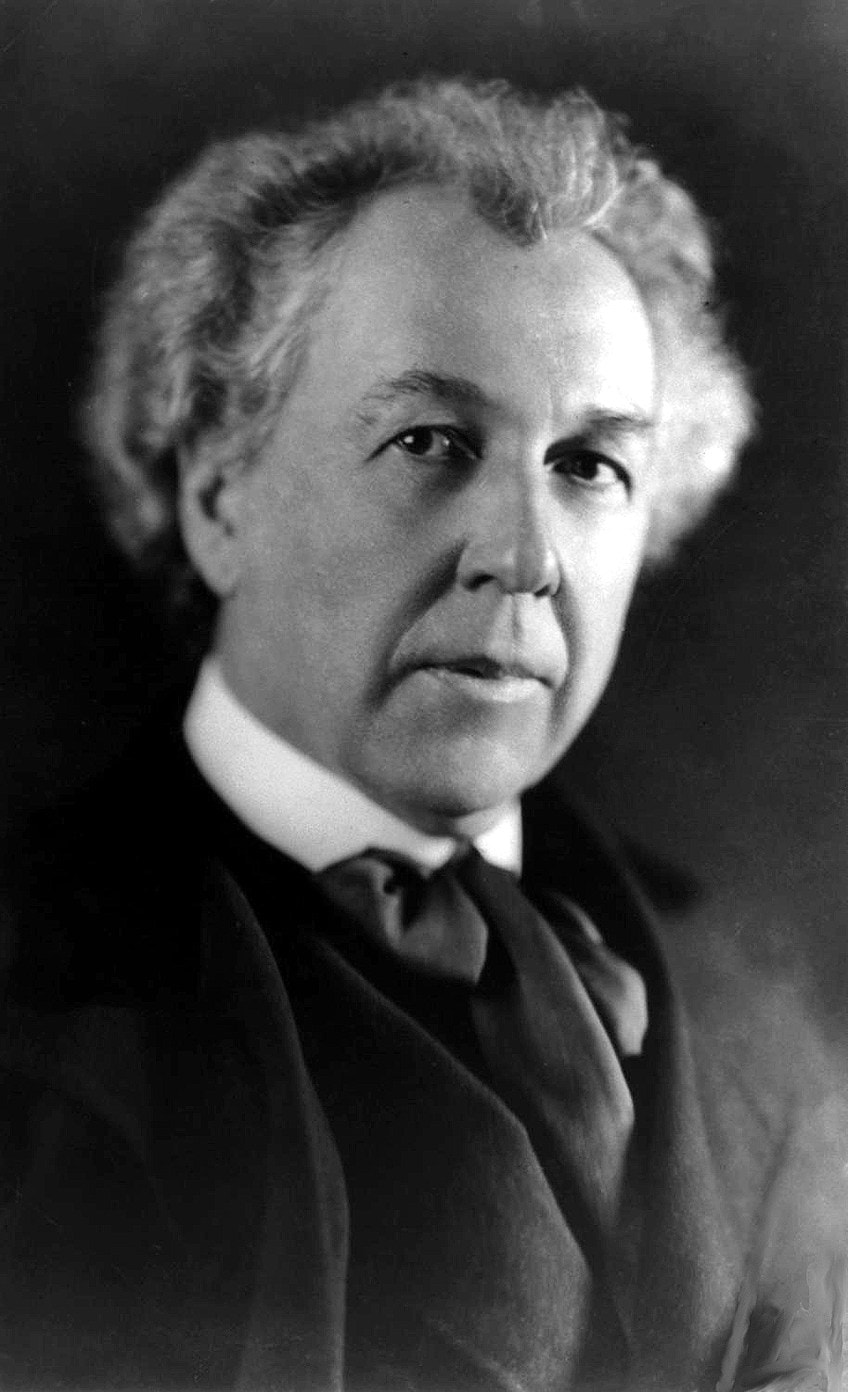

Frank Lloyd Wright was born in Wisconsin, on the 8th of June, 1867. Anna Lloyd Jones, Wright’s mother, was a teacher from a big household that had moved from Wales. William Carey Wright, his father, was a pastor and pianist.

Early Life

The Wright family moved around fairly regularly during his childhood, residing in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Iowa before they finally settled in Wisconsin when Wright was about 12 years of age. Wright’s parents split in 1885, the year he finished high school, and his father decided to move away for good and was never seen again. Wright then enrolled in university that year to pursue civil engineering. He worked for the head of the engineering faculty, and the respected architect, Joseph Silsbee, with the development of the Unity Chapel to cover his fees and provide for his family.

The trip left him with a lasting desire to become an architect, and he left school in 1887 to assist Joseph Silsbee in Chicago.

The Emergence of the Prairie School

The following year, he undertook an apprenticeship with the Chicago architectural company of Adler and Sullivan, where he worked closely with Louis Sullivan, the famed architect from America regarded as the “Godfather of Skyscrapers.” Sullivan, who eschewed elaborate European forms in the pursuit of a cleaner aesthetic summarized by his adage “form follows function”, had a great impact on Wright, who would finally carry out Sullivan’s aim of creating a distinctly American architectural style.

Wright worked with Sullivan until 1893 when he violated their agreement by soliciting private contracts to design residences, and the two went their own ways.

In 1889 Wright married Catherine Tobin, and they had six children together. Their house in Chicago’s Oak Park neighborhood is regarded as the first of Wright’s famous architectural houses. After leaving the firm he had been working for in 1893, Wright launched his own architectural firm there.

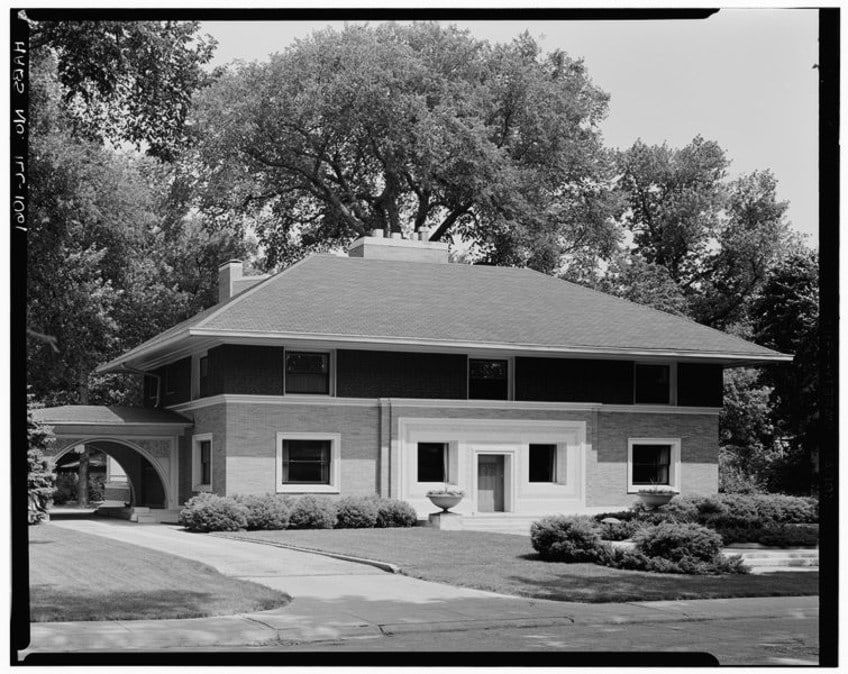

The Winslow House in River Forest, constructed in 1893, is the earliest illustration of Wright’s groundbreaking style, subsequently termed “organic architecture,” with its horizontal orientation and large, airy interior spaces.

Wright constructed a number of homes and public structures over the following few years, that became known as the “Prairie School” style of architecture. They were single-story dwellings made from locally accessible materials and timber that was always left untreated to emphasize its natural beauty. The Unity Temple and the Robie House are two of Wright’s most famous “Prairie School” structures.

While such achievements established Wright as a personality and his architecture received widespread recognition in Europe, he remained largely unrecognized outside of design communities in the United States.

The Construction of Taliesin and Other Developments

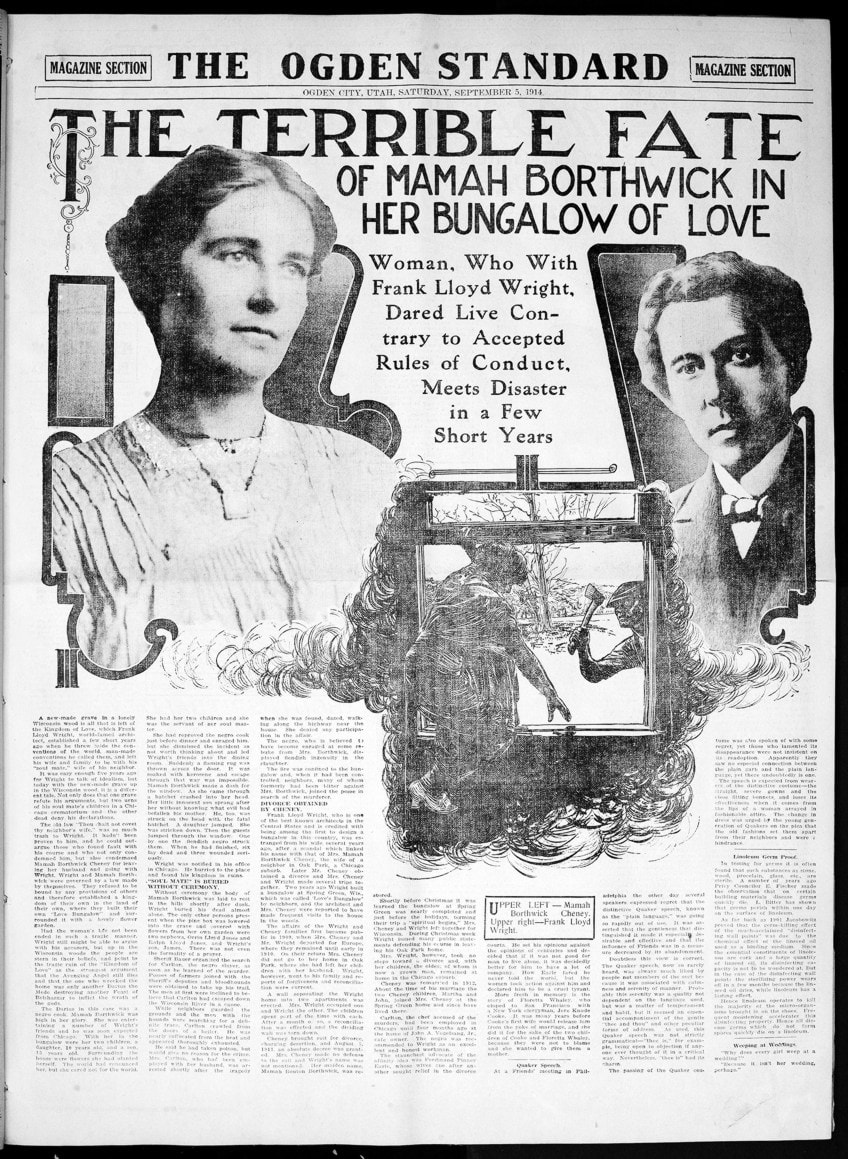

Wright abruptly abandoned his family and company in 1909 and relocated to Germany with a lady called Mamah Cheney, the fiancée of a customer. While in Germany, he created two portfolios of his architecture, raising his global status as one of the greatest living designers.

Near 1913, Wright and Cheney moved to the US, and Wright constructed a home for them in Spring Green dubbed Taliesin, which means “shining brow” in Wales, and it would become one of his most appreciated masterpieces.

However, disaster followed in 1914, when a disturbed domestic worker set fire to the home, destroying it and killing Mamah Cheney as well as six other people. Despite his grief over the death of his beloved and residence, Wright instantly started reconstructing Taliesin in order to erase the wound from the hillside and his heart.

Wright was appointed by the Japanese Emperor to construct the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo in 1915. He worked on the project for the following seven years, creating a stunning and groundbreaking structure that Wright said was resistant to earthquakes. In 1923, a devastating earthquake, which ravaged the city only one year after its erection, put the architect’s assertion to the challenge.

The only significant building to withstand the earthquake was Wright’s structure.

When he returned to the United States in 1923, he wedded sculptor Miriam Noel; and they were married for four years before deciding to separate. Yet another fire destroyed Taliesin in 1925, prompting him to reconstruct it once again. Wright then engaged Olga Lazovich, his third wife, in 1928.

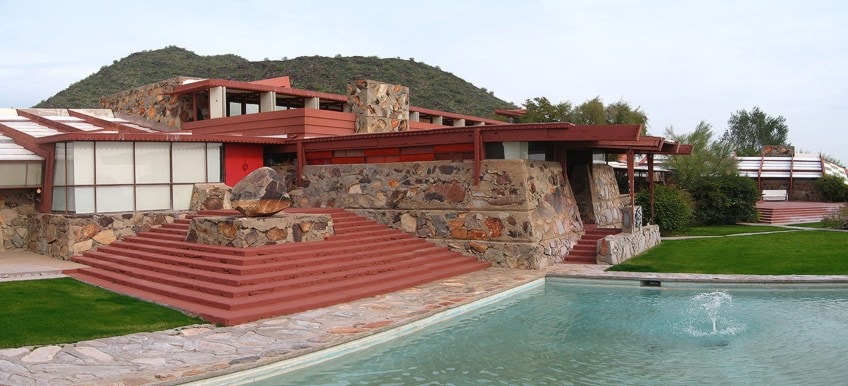

When construction jobs dried up in the early 1930s owing to the Great Depression, Wright turned to literature and lecturing. He released an autobiography that become an architectural classic. The Taliesin Fellowship, an experiential design institution operating out of his own house and workshop, was created the same year. Around five years later, he and his students began construction of Taliesin West, an Arizona mansion and studio that accommodated the Taliesin Society during the wintertime.

The Building of Fallingwater House

As wright approached his 70s, He seemed to have calmly retired to administer his Taliesin Fellowship before exploding back onto the national spotlight to create several of his life’s finest masterpieces. Fallingwater, a mansion for Pittsburgh’s famed Kaufmann family, marked Wright’s reentry to the industry in a spectacular way in 1935. Fallingwater is a complex of overhanging terraces and balconies built over a waterfall in rustic southwestern Pennsylvania that is both startlingly innovative and breathtakingly beautiful.

It is still one of Wright’s most famous masterpieces, a state landmark widely regarded as one of the most exquisite houses ever designed.

Final Years

Wright started work on the Guggenheim Museum in 1943, a project that would dominate the next 16 years of his life. The museum is a massive white tubular structure rising upwards through a Plexiglas dome, with a solitary gallery alongside a slope that spirals up from the bottom floor. While Lloyd’s design was divisive at the time, it is today regarded as one of New York City’s best structures. Wright died on the 9th of April, 1959, at the age of 91.

He is widely regarded as the finest designer of the 20th century and the best architect to emerge from America, having mastered a uniquely American architectural style that stressed purity and natural aesthetics in comparison to Europe’s ornate and opulent architecture.

Wright planned almost 1,100 structures throughout his career, roughly a third of which were completed during his last years, with extraordinary energy and determination. After around 20 years of struggle, his burst of inspiration was one of the most stunning revivals in the history of American architecture. Wright’s legacy lives on through the stunning structures he created, as well as the compelling and enduring notion that motivated all of his work – that structures should respect and augment the beauty that surrounds them.

Legacy

Following Wright’s death, his apprentices labored to complete the remaining projects assigned to him, including the Marin County Civic Center in California, which is considered one of Wright’s most notable achievements. Wright’s place as America’s finest architect is guaranteed. Together with his hundreds of dwellings, he created practically every sort of structure. The Museum of Modern Art has dedicated more one-person displays to his works than any other designer.

Further than that, though, Wright’s personal reputation is often in dispute. Wright professed a theoretically egalitarian architectural philosophy, yet he gradually became elitist and dismissed the general populace as crude and ignorant.

His large ego frequently got in the way of friendships, especially those with those nearest to him, and there were very few individuals who Wright considered equals. Wright struggled with setting boundaries for his ambitions, and many of his authors see him as simply a juvenile who never fully matured.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Famous Architectural Houses and Designs

Wright was an outspoken individual in both ideals and architecture. Yet, he acquired a large number of students in the latter half of his career, primarily through the formation of the Taliesin Fellowship, a type of internship on his land where his pupils aided him in both architecture and agricultural labor.

Following his passing, some of his students, like Edgar Tafel and William Wesley Peters, rose to prominence as renowned architects in their own capacity.

Unity Temple (1908)

| Date Completed | 1908 |

| Function | Church |

| Materials | Concrete |

| Location | Oak Park, Illinois |

Unity Temple was among Frank Lloyd Wright’s first big non-residential commissions. It is also the very first of his several churches, created for his own community in Oak Park after the prior facility was burned to the ground, and it continues to be his most prominent religious construction. After a huge stabilizing and repair effort, the church reopened in 2017. The church’s entry is indirect, accessed from the side, as are most of his Prairie Style structures, and to approach the sanctuary, one would need to make three turns to the right, presumably highlighting the connection with a prolonged spiritual trip to illumination.

Once inside, the visitor traverses a buried corridor underneath the central sanctuary floor and then ascends several steps to emerge onto its square center floor area, as if ascending to a higher level. The seating is positioned in terraces on three sides and in the middle square, with the altar comprising the fourth side.

This layout emphasizes a feeling of unity by bringing the congregation together in close proximity.

The interior’s brown, green, and golden hues, characteristic of Wright’s early phase, imply a link with the earth, which is emphasized by natural light streaming in through skylights as if one were seated in a shaded meadow of trees. The positioning of the windows in the massive concrete construction, which Wright chose for its inexpensive cost, serves to limit street and traffic noise.

As a result, the interior’s mood is one of extraordinary tranquility, quiet, and relaxation.

Dining Room Ensemble, Burton J. Westcott House (1908)

| Date Completed | 1908 |

| Function | Dining room |

| Materials | Furnishing |

| Location | Springfield, Ohio |

Frank Lloyd Wright’s furnishings are still highly respected among American architects. Because Wright liked to create practically everything when granted a contract, the furnishings frequently became pieces of art in their own right, effortlessly incorporated into the rest of the structure’s style – echoing organic architectural concepts.

It also implies that Wright’s furnishings were often custom-designed for specific residences and that each house’s interiors are distinct from the others.

Wright’s dining rooms, particularly those from his Prairie-style period, are representative of various features of his interior design. The most essential of these is the fostering of social contact and assembly, which Wright does in a variety of ways.

The high-backed seats assist to block off the views behind each individual seated at the table, centering everyone’s focus on the people sitting around the table. The chairs’ upright backs promote correct posture, though this type of seating is infamously uncomfortable to sit in.

Many other Frank Lloyd Wright furniture pieces, on the other hand, are extremely practical and comfortable; thus, this is not a distinguishing feature of Wright’s furniture.

The lamps affixed at each side add to the sense of community by illuminating the table and inviting guests to sit down while also obstructing peripheral glimpses outside of the present company. Because of their fixed connection to the floor for the electric wires, the lamps further represent the table’s purpose as a base for the room, and in a broader context, this concept of stabilizing and anchoring objects within a space conveys Wright’s idea of an entire building operating as a shining beacon of reliability and safety in the throes of a progressively shifting, unsteady, industrial civilization.

Imperial Hotel (1922)

| Date Completed | 1922 |

| Function | Hotel |

| Materials | Brick |

| Location | Tokyo, Japan |

The Imperial Hotel was perhaps Wright’s first important project, showcasing his engineering ability clearly and spectacularly. He worked hard to obtain the contract, for which the Japanese government wanted him to create a Western-style accommodation facility that would be appealing to outsiders. His reaction was a brick tower that would become one of the 20th century’s last significant hand-built structures, done in a type of Mayan Revival design that, strangely, must have appeared about as foreign to Americans and Europeans as it did to the Japanese.

Wright created practically everything related to the facility, down to the dining table crockery and cutlery, making it a total work of art.

These characteristics, together with his use of new technology demonstrate how Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture at the midpoint of his career mirrored both the principles of the Arts & Crafts tradition as well as the developments of the modern world.

Fearing earthquakes, Wright built the Imperial Hotel as a collection of distinct, connected pavilions with buoyant foundations placed on concrete piles pushed deeply into the earth below, letting the pavilions shift autonomously in the event of seismic activity. The reception and social amenities were located in the center wing, which joined twin wings housing the rooms arranged perpendicular to it.

An earthquake rocked Tokyo just over a year after the resort’s inauguration in 1923, confirming Wright’s ingenuity.

When word came that the hotel had not only endured with just minimal damages but also shone like a beacon of promise among the flames and ruins of most of the center of the town, Wright was acclaimed as a structural magician for a brief time.

Despite the fact that several other Tokyo structures survived the calamity, Wright did little to dispel the myth that his hotel was the only one to remain unscathed.

The hotel was razed in 1968 and rebuilt with a new high-rise layout, a casualty of changing preferences, World War II devastation, the irregular natural sinking of the substructure, and the necessity to house an exponentially greater number of visitors in a metropolis where land was limited.

Its centerpiece, on the other hand, was spared and transferred to Nagoya, where it was meticulously repaired over a 17-year period and is now the property of the Meiji-Mura Museum.

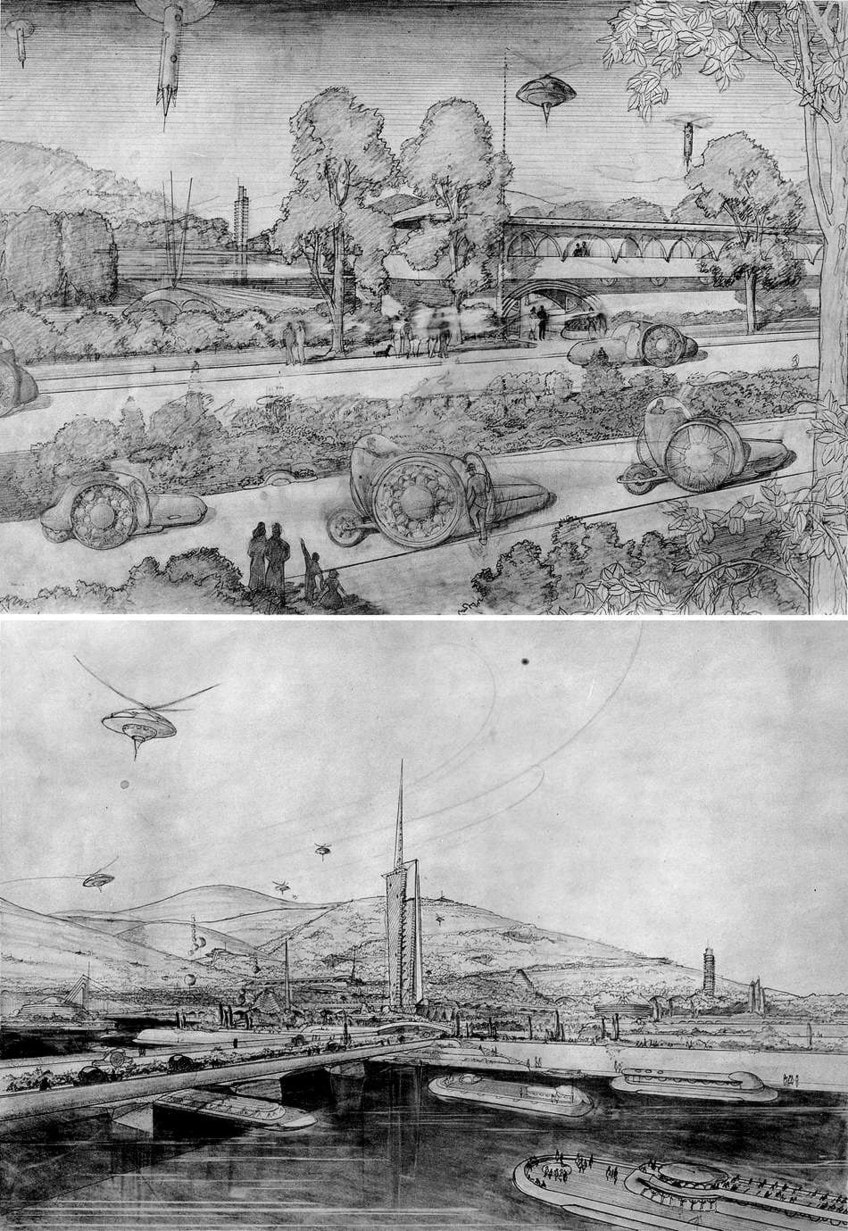

Broadacre City (1932)

| Date Completed | 1932 |

| Function | City Plan |

| Materials | Blueprint sketches |

| Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York |

The Broadacre City plans, though never built and never completed, are the most thorough articulation of Wright’s concept of what American urbanization could look like. Wright first proposed the design for Broadacre City in his The Disappearing City (1932) book, whose title sentence encapsulates Wright’s view on urbanization. During a three-year period when there were no legitimate clients, Wright kept his Taliesin students occupied by designing the prototype for Broadacre City. Edgar Kaufmann, the person who acquired Fallingwater as his holiday home, funded the building.

In 1935, Wright displayed the design in Rockefeller Center and he would keep tinkering with it until his death. Broadacre City is a metropolis stretched across several acres of farmland, with the car serving as the major mode of transportation by design.

The area is divided into numerous zones for diverse uses, essentially along a grid road design, separating housing, business, commercial, and municipal structures and incorporating them with agriculture.

Excluding a few apartment blocks, nearly all the structures in the design are low-rise. As the project progressed, Wright’s new construction ideas would regularly appear in the drawings portraying the city plans in his publications. Broadacre City was designed in the years of the Great Depression, around the same period as other design-phase urban projects that likewise attempted to develop a rigid zoning scheme and car-based transport.

In America in the postwar period, with the emergence of urban renewal initiatives, a variant of Wright’s dream would materialize, but with highly contentious and frequently disastrous results, such as replacing urban-dwelling minorities who ended up in remote rural areas.

These strategies represent the confidence that planners had in the car to completely remold Western civilization once the economy recovered again.

Fallingwater House (1937)

| Date Completed | 1937 |

| Function | Residence |

| Materials | Cement, river gravel |

| Location | Mill Run, Pennsylvania |

Fallingwater, perhaps the most well-known contemporary home in the world and Wright’s most well-known structure, is frequently credited with reviving his career. The Pittsburgh chain store tycoon Edgar Kaufmann, Sr. had it constructed as a family holiday house. Fallingwater is mostly Frank Lloyd Wright’s answer to the avant-garde International Style European architects like Le Corbusier.

With a core of locally sourced stone that supports the home on the crag above Bear Run, Fallingwater successfully embodies Wright’s theory of organic design, which sought to incorporate structures into the landscape.

To maintain the Kaufmanns’ favorite resting location above the falls, Wright constructed the home around it, enabling its rock to peek through the living room flooring. From afar, the house seems like a succession of abstracted rectangular terraces hanging in the treetops above Bear Run River, so that you can almost always hear but not see it from inside the house.

The legend surrounding Fallingwater’s construction, as well as its subsequent history, has further contributed to its prominence.

It is also the most notable case of Wright’s mistakes since its lower cantilevers started falling almost immediately after construction owing to insufficient steel reinforcing, despite repeated concerns voiced by other designers at the time. In 2002, the home reportedly underwent a thorough post-tensioning restoration to support the terraces.

As a consequence, it is now one of the most noteworthy examples of both historical conservation and structural engineering.

Johnson Wax Administration Building (1945)

| Date Completed | 1945 |

| Function | Administration building |

| Materials | Concrete, sandstone |

| Location | Racine, Wisconsin |

Wright’s Johnson & Son building, headquarters of the popular household goods manufacturers, represented the comeback of his profession in the latter part of the 1930s and early 1940s. Because the firm chairman Herbert Johnson asked him to build it for Racine’s downtown, which was an abomination of an industrial district, Wright ruled that there would be no outside windows. The Johnson Wax structures are Wright’s epitome of a more severe, streamlined outgrowth of Art Deco.

Despite the fact that the confined area is shut off from the outside world, it features several allusions to nature. A network of dendriform columns divides the major interior area.

Wright lined the crevices between the pillars with Pyrex skylights, which made it very challenging to seal but is now utilized widely throughout the structure as one of its trademark characteristics. The workroom’s luminous radiance when saturated with natural light and bustling with activity has evoked analogies to a beehive.

The research building, one of two skyscrapers constructed by Wright during his lifetime, marks his most significant structural improvement of the kind. It employs a core column with a foundation of piles buried deep into the earth, and all of the floors are projected off of the vertical framework like tree limbs. Its shape is similar to that of a battery, which may represent how scientific research is used to generate the company’s domestic items.

Frank Lloyd Wright pushed American architecture into the spotlight in his distinguished career. His creative works were heavily influenced by nature, and he stressed artistry while adopting technology’s power to make design available to everybody. Wright was also heavily involved in the interior decoration of his structures, producing furniture and other unique components like stained-glass panels to complement the overall visual appearance. Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture will forever be appreciated by architects across the globe for its unique design.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Frank Lloyd Wright?

If one were to ask the typical American to mention a prominent American architect, you can be sure they will choose Frank Lloyd Wright. He had such cultural clout for good reasons: he revolutionized the way we construct and inhabit spaces. How many Frank Lloyd Wright houses are there, though? Well, he developed some of the most inventive locations in the United States by conceptualizing more than 1,110 structures of different sorts, more than 530 of which were built. Wright’s imaginative work solidified his reputation as the best American designer of all time with a career spanning seven decades.

Where Was Frank Lloyd Wright Born?

Frank Lloyd Wright originally came from Richland Center, which is in Wisconsin. But when did Frank Lloyd Wright die? You may be interested to know that he passed away on the 9th of April, 1867, in Phoenix, Arizona.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Frank Lloyd Wright – Who Was Frank Lloyd Wright, the Architect?.” Art in Context. August 18, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/frank-lloyd-wright/

van Huyssteen, J. (2022, 18 August). Frank Lloyd Wright – Who Was Frank Lloyd Wright, the Architect?. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/frank-lloyd-wright/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Frank Lloyd Wright – Who Was Frank Lloyd Wright, the Architect?.” Art in Context, August 18, 2022. https://artincontext.org/frank-lloyd-wright/.