Georgia O’Keeffe – Mother of Modern Feminist Art

The mystique of Georgia O’Keeffe’s exceptional life is as intriguing as her stunningly bold abstract paintings. Georgia O’Keeffe is one of the main founders of modern art at the beginning of the 20th century, and she is often referred to as the American mother of modernism. This article explores the remarkable life and wonderful work of Georgia O’Keeffe.

Table of Contents

- 1 Artist In Context: Who Was Georgia O’Keeffe?

- 2 Seminal Works by Georgia O’Keeffe

- 2.1 Drawing XIII (1915)

- 2.2 Blue #2 (1916)

- 2.3 Blue Line (1919)

- 2.4 Petunia No. 2 (1924)

- 2.5 Radiator Building – Night, New York (1927)

- 2.6 Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue (1931)

- 2.7 From the Faraway, Nearby (1937)

- 2.8 Red and Yellow Cliffs (1940)

- 2.9 Pelvis II (1944)

- 2.10 Black Place, Grey and Pink (1949)

- 2.11 Sky Above Clouds IV (1965)

- 3 O’Keeffe’s Final Years

- 4 Book Recommendations

- 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Artist In Context: Who Was Georgia O’Keeffe?

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) is an American artist best known for her large abstract paintings inspired by nature. Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings are among the most influential in the rise of Modernism and her themes included flowers, bones, the natural and architectural landscapes of New Mexico, and cityscapes of New York City. In her early years, O’Keeffe was a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, and she was part of the Art Students League in New York.

She married the photographer Alfred Stieglitz in 1924, eight years after he had given her her first solo show in his gallery in 1916. After the death of Stieglitz, O’Keeffe moved to New Mexico to the landscapes that she has loved so much. She stayed here till the end of her life, where she created many famous paintings inspired by the New Mexico landscape.

| Date of Birth | 15 November 1887 |

| Date of Death | 6 March 1986 (age 98) |

| Country of Birth | Sun Prairie, Wisconsin |

| Art Movements | Modernism, Abstraction, Precisionism |

| Mediums Used | Charcoal, Watercolor, Oil Paint |

Birth and Early Life

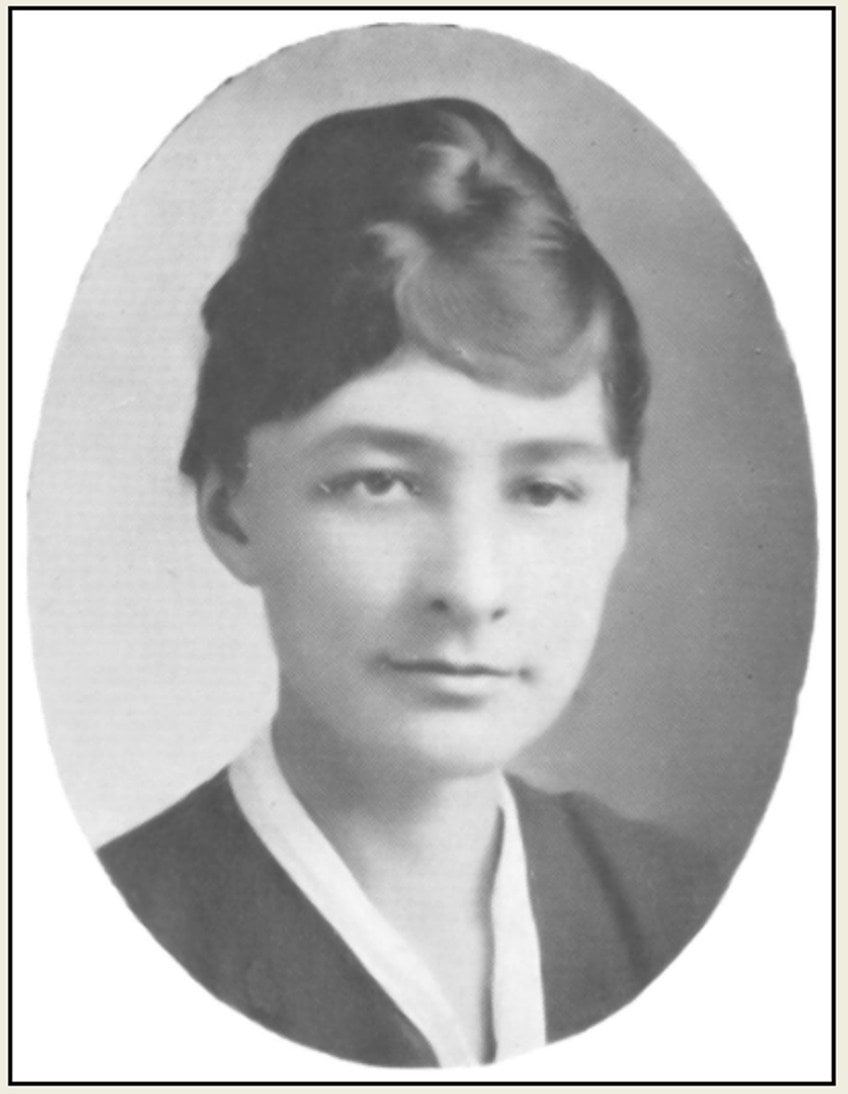

Georgia O’Keeffe, a painter at heart, was born on the 15th of November 1887. She was born the second of seven children and spent her early years growing up on a wheat farm in Wisconsin. O’Keeffe’s father, Calixtus O’Keeffe, was Irish, and her mother, Ida Totto, was Dutch and Hungarian. Georgia O’Keeffe was named after her Hungarian grandfather, named George Totto.

O’Keeffe’s family was supportive of her interest in art and the natural environment from a very young age.

Many women in O’Keeffe’s family enjoyed painting, and her mother, who regarded her children’s education very highly, arranged art classes for O’Keeffe from a young age. O’Keeffe’s interest in art did not diminish during her schooling years at the stringent Sacred Heart Academy in Wisconsin. When O’Keeffe’s parents moved to Virginia in 1903, O’Keeffe stayed behind in Wisconsin, living with her aunt, to attend Madison High School for one more year.

By the age of 15, Georgia O’Keeffe’s art was already developing well, and she decided to join her parents in Virginia where she attended a boarding school called Chatham Episcopal Institute. O’Keeffe’s many different teachers throughout her schooling career all supported her passion for art.

Already after graduation, Georgia O’Keeffe was a painter, and her determination to become a professional artist was at an all-time high.

Early Career

After graduating from high school, O’Keeffe attended the Art Institute of Chicago (1905 – 1906), and thereafter, in 2907, she continued her studies at the Art Students League in New York City. During her studies, O’Keeffe visited many art galleries and was particularly interested in the art gallery that was owned by two photographers, namely Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen.

This gallery was particularly interesting as it was one of the only galleries to exhibit avant-garde works of modern American and European artists.

At the Art Students League, she studied realist painting and was highly influenced by her lecturer William Merrit Chase. O’Keeffe won the William Merrit Chase Prize for a realist painting titled Dead Rabbit with Copper Pot (1908). This prize earned her the opportunity to attend an artist residency summer school at Lake George in New York. Although O’Keeffe was a good realist painter, she felt that her work was not unique enough, and she decided to abandon her career as a painter in exchange for being a commercial artist instead. She returned to Virginia in 1910 to live with her family, who had fallen on hard times.

In 1912, O’Keeffe took an art class with Alon Bement, presented at the University of Virginia.

At the time, Bement was a faculty member of Teachers College at Columbia University and went to Virginia to give the art class as part of the University of Virginia’s summer school program. Bement had a big influence on O’Keeffe’s work and rekindled her excitement about being an artist. Columbia University had revolutionary ideas of art, inspired by the vision of Arthur Wesley Dow, that refreshed O’Keeffe’s own ideas. She became influenced by Japanese art and the more abstract expressions that it valued.

Whilst O’Keeffe was experimenting with her own art, she decided to teach art in public schools in Texas. During summer school, she acted as Bement’s teaching assistant.

In 1915, O’Keeffe started teaching at Columbia College in Columbia. Whilst teaching, O’Keeffe worked on a body of charcoal drawings that were purely abstract. She mailed her drawings for review to her friend, Anita Pollitzer, who subsequently showed it to the avant-garde gallery owner, Alfred Stieglitz. Georgia O’Keeffe was one of the first American artists to have created purely abstract works, so when Stieglitz saw her work, he was immediately impressed and decided to include ten of her works in a group show in 1916. In April 1917, Stieglitz sponsored Georgia O’Keeffe’s first solo show in his gallery, called Gallery 291.

O’Keeffe, Stieglitz, and New York City

O’Keeffe and Stieglitz started corresponding after he first saw her work. In 1918, a year after her first solo show, O’Keeffe moved to New York into an apartment that Stieglitz found for her. Stieglitz supported O’Keeffe financially so that she would be able to place her focus on developing her work.

Their connection kept developing and soon they fell in love with each other, starting an affair regardless of Stieglitz being married or that he was 23 years O’Keeffe’s senior. Stieglitz divorced his wife and in 1924, he married O’Keeffe. O’Keeffe and Stieglitz lived together in New York and went to Stieglitz’s family home in Lake George during the summer.

O’Keeffe was also the subject of Stieglitz’s art.

At the time, it was controversial for Stieglitz to promote his photography as an art form. Even more controversial were the images of O’Keeffe as his subject matter. Stieglitz took Georgia O’Keeffe’s portrait for many of his work, but a lot of his images were much more sensual and sexual. Stieglitz exhibited many nude photographs of O’Keeffe, often abstracting the image by cropping out many of the details.

This cropping of the image to abstract the subject influenced O’Keefe’s own work and she started to abstract her paintings of flowers by cropping out the outer shapes and only painting the inner details and large colorful shapes.

When O’Keeffe exhibited these works for the first time, in a solo show at the Anderson Galleries in 1923, it was seen by the viewers and critics in the same light as Stieglitz’s photographs of her. The result was an overly Freudian reading of her new work and people described her works as being extremely sexual. At the time, O’Keeffe was a member of one of the National Woman’s Party, and she vehemently denied the sexual connotations imposed onto her work by the public and attested that her work is purely inspired by nature and abstraction.

O’Keeffe and Stieglitz started working on reshaping her public image by arranging further exhibitions, interviews, and new photographs that posed her in a different light.

Stieglitz had continued to support O’Keeffe’s career and held annual solo exhibitions for her until his death. This included exhibitions at the Anderson Galleries in 1924 and 1925, at the Intimate Gallery from 1925 until 1929, and at An American Place from 1929 to 1946. By this, Stieglitz helped O’Keeffe in becoming one of New York’s most celebrated Modernist artists. In O’Keeffe’s career, she enjoyed financial security from her work, which gifted her with complete independence.

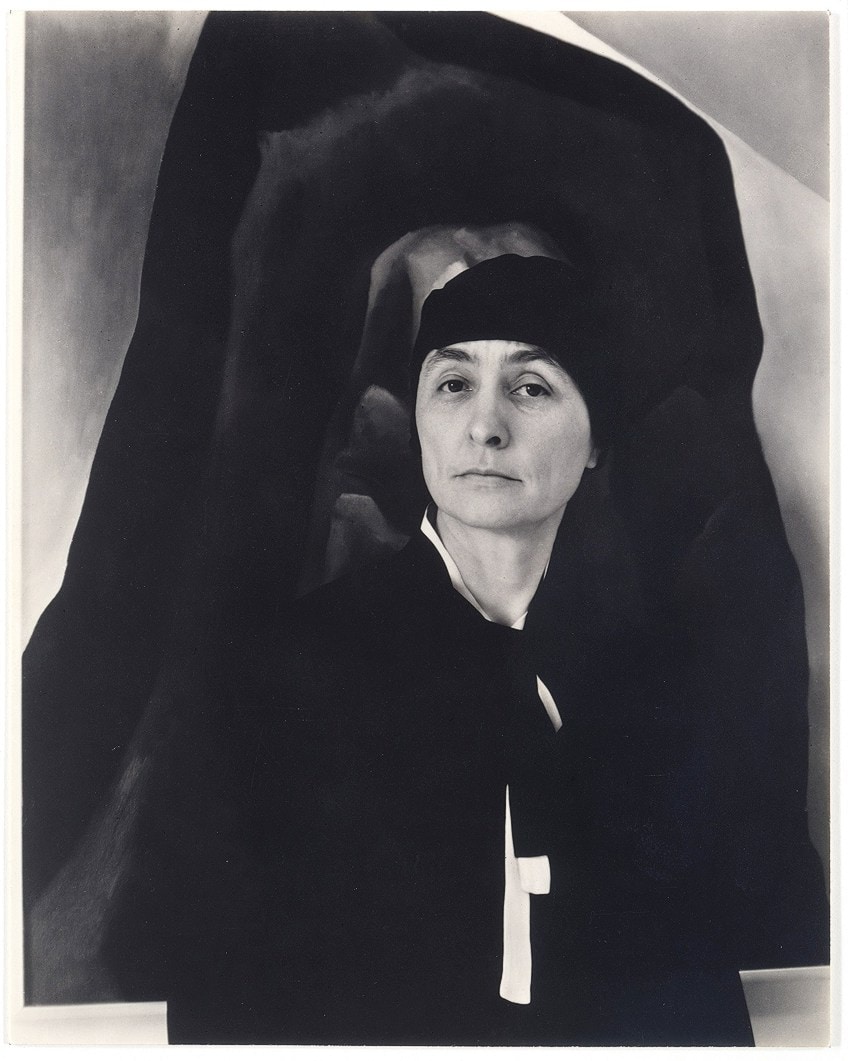

Georgia O’Keeffe: A Portrait by Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz was a photographer before he met Georgia O’Keeffe, but it is only when his love affair with O’Keeffe started that his photographs really came alive. Between 1918 and 1920, Stieglitz produced more than 140 final works from the photographs of O’Keeffe.

Initially, Stieglitz photographed O’Keeffe in front of her own drawings and paintings, but as their love grew, and as O’Keeffe became more comfortable in front of the camera, the images became more intimate, emotional, and sensual.

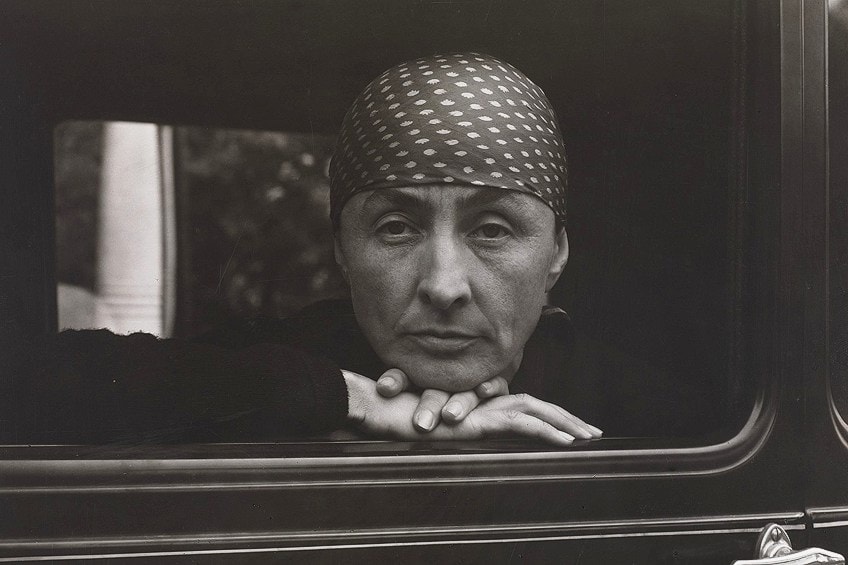

Some photographs were portraits where O’Keeffe looks directly into the camera, revealing her body only slightly and giving off the sense of longing. An example of such a work can be seen below in the photograph titled Georgia O’Keeffe: A Portrait (I) (1918).

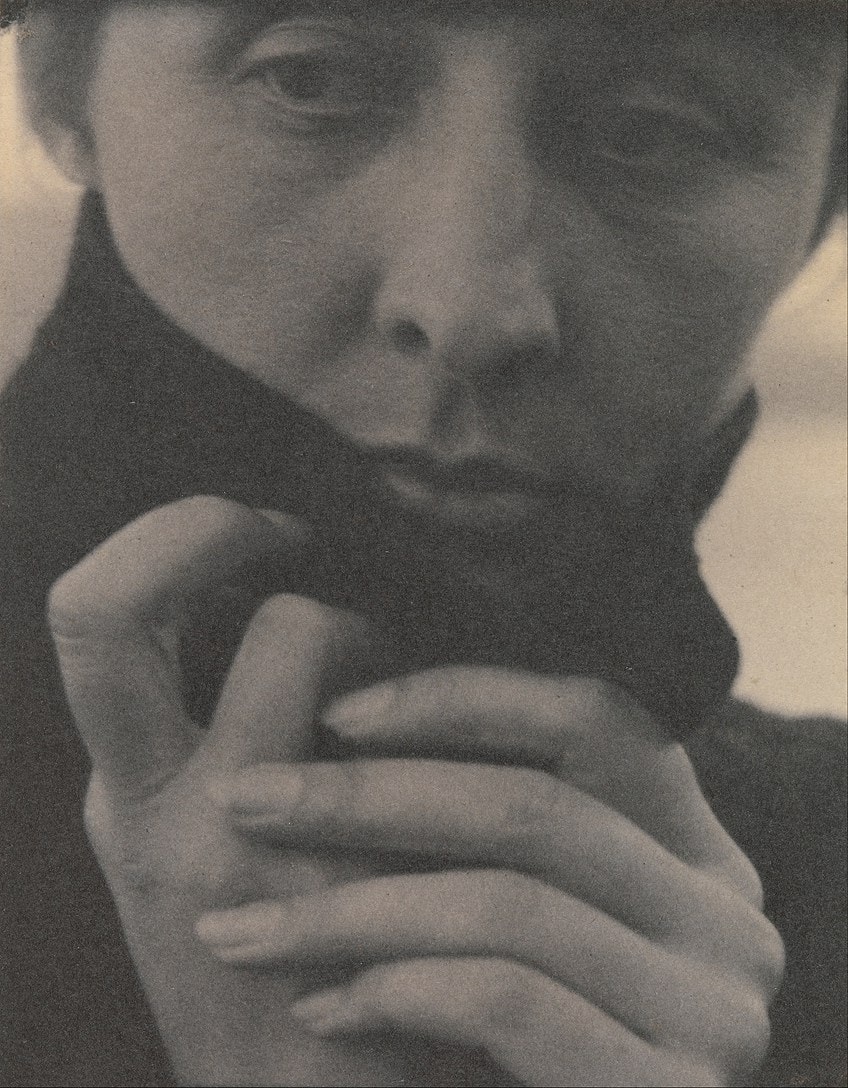

Other works were much more intimate, showing isolated parts of her nude body, abstracted by cropping out many other details in the image. Some of these photographs were cropped views of O’Keeffe’s legs, hands, torso, and feet.

Stieglitz saw these images not only as single artworks to stand by themselves but also as a collection of works that, when placed together, communicate something of O’Keeffe’s presence in his life over time.

Whilst these photographs were beautiful and unique, it was detrimental to O’Keeffe’s own artistic image as they promoted unwanted sexual readings onto her own work, which she did not want. An example of such an image can be seen in Stieglitz’s 1919 photograph of O’Keeffe holding her breasts.

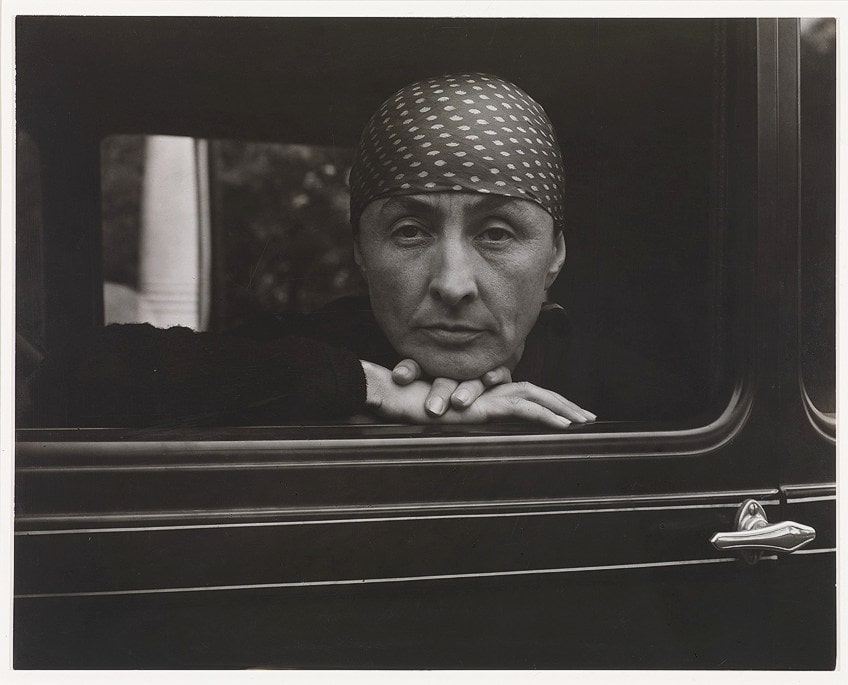

Stieglitz continued to photograph O’Keeffe after the 1920s, but his photographs became less intimate and rather promoted an image of O’Keeffe not as he saw her, but as she wanted to be seen by the public. The later photographs did not show the sensual side of O’Keeffe, but rather her independent side and determined nature. His composite portrait of O’Keeffe eventually consisted of 331 works. One of his later photographs of O’Keeffe, taken in 1932, shows her looking directly at the camera through a window of a car or a train, highlighting the independent spirit of Georgia O’Keeffe.

New Mexico and Her Mature Career

Georgia O’Keeffe’s art career experienced exceptional growth in New York, but by the end of the 20th century, she felt uninspired by city life. Nor did the yearly visits to the lush landscape of Lake George inspire her anymore. O’Keeffe felt torn between her commitment towards her husband and her need for a change in environment. In 1929, however, she decided to spend the summer at an artist residency in New Mexico, a space that she visited briefly in 1917 and that always pulled her in. Here she rediscovered her love for vast landscapes with large open skies, similar to that of her childhood.

O’Keeffe was also inspired by the unique architecture of the place and by the local Navajo culture. She returned here for many years to spend her summers in New Mexico.

O’Keeffe loved the New Mexico landscape and called it “the faraway”. She loved the remote feeling of being so distant from her life in New York. Since childhood O’Keeffe was reclusive and enjoyed spending time by herself. For several years O’Keeffe split her time between living with Stieglitz in New York and enjoying her solidarity in New Mexico. It is during her summers in New Mexico where she painted famous works like Black Cross, New Mexico (1929) and Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue (1931) and Ram’s Head, and From the Faraway, Nearby (1937).

O’Keeffe especially enjoyed working in Ghost Ranch, located north of Abiquiú, and in 1940 she bought a house there. In 1945, she bought a second house in Abiquiú. In 1946, Stieglitz passed away at the age of 82. O’Keeffe was with Stieglitz when he died and three years after his passing, she moved permanently to New Mexico.

In 1959, O’Keeffe started traveling more, visiting many sites that inspired her all over the world.

A lot of her paintings from this time were inspired by the views through airplane windows. These works offered a new perspective for her on abstraction, one of which was called Sky above Clouds IV (1965). Other works inspired by these window views were more topographical of the earth beneath and can be seen in works such as Blue, Black, and Grey (1960).

Seminal Works by Georgia O’Keeffe

Georgia O’Keeffe created over 2000 works during her life and her innovative paintings became the most recognizable in the American Modernist art movement. O’Keeffe’s work was showcased in a large retrospective exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, and in 1945, Georgia O’Keeffe was the first female artist to have had a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. A selection of Georgia O’Keeffe paintings will be discussed in more detail in the sections to follow.

The works are placed in chronological order to show the development of Georgia O’Keeffe’s art style throughout her career.

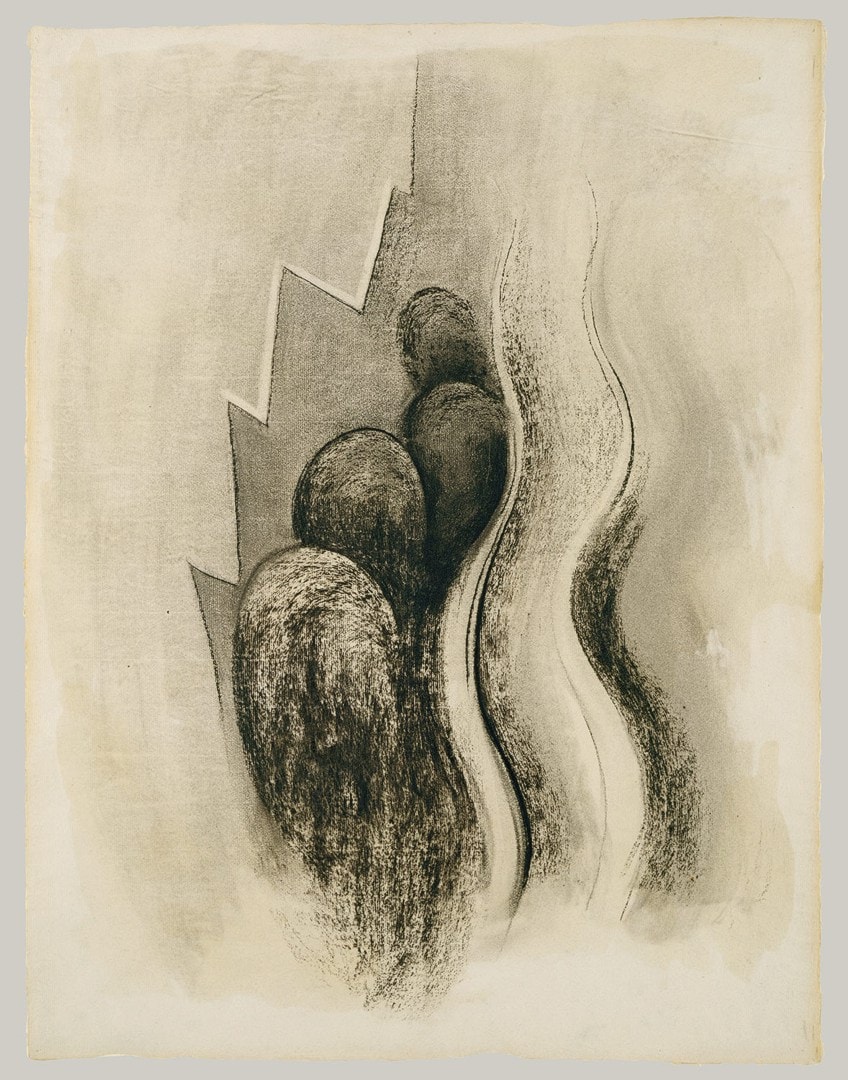

Drawing XIII (1915)

| Artwork Title | Drawing XIII |

| Date | 1915 |

| Medium | Charcoal on paper |

| Size | 61.9 cm x 47 cm |

| Collection | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Drawing XIII is a Georgia O’Keeffe artwork that truly marked her independence from traditional education and showed her unique style. O’Keeffe’s early drawings were made on large sheets of paper, using bold gestural strokes of charcoal.

At the time, O’Keeffe made work out of charcoal to truly focus on the compositional and abstract elements of the work, and only later, when she felt like she mastered this, did she include color in her work again.

Drawing XIII consists of three parallel sections, consisting of flowing river-like lines on the right, four circular shapes referencing hills or trees in the center, and a jagged lightning-like line at the left that resembles mountains. This is one of the first works that Stieglitz saw of O’Keeffe, and he included it in her first solo show in 1916 that he held at gallery 291.

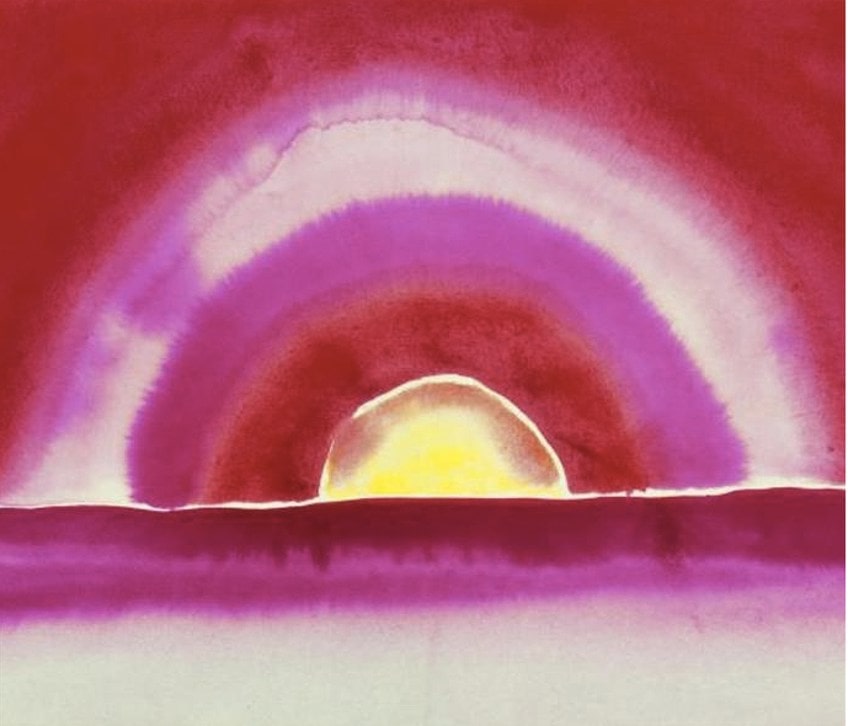

Blue #2 (1916)

| Artwork Title | Blue #2 |

| Date | 1965 |

| Medium | Watercolor on paper |

| Size | 40.3 cm x 27.8 cm |

| Collection | Brooklyn Museum |

In Blue II, O’Keeffe had started to reintroduce color into her work, though at this stage, the color was still mostly monochromatic. The focus of this work is however not on color theories, but rather on the movement of the abstract shape.

O’Keeffe was familiar with the way that Kandinsky used color to convey music, and it is possible that this color theory was an influence on O’Keefe’s choice of blue.

While the shape in this work is abstract enough to have a reference to many different natural forms, it is possible that the inspiration came from the spiral shape at the end of a violin, an instrument that O’Keeffe was playing at the time of creating this work.

Blue Line (1919)

| Artwork Title | Blue Line |

| Date | 1919 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size | 51.2 cm x 43.5 cm |

| Collection | Georgia O’Keeffe Museum |

Blue Line (1919) is one of O’Keeffe’s earliest examples of abstract works inspired by flowers. It is these paintings that made her famous. The edges of the flower are cropped, showing only the inside forms. The color, form, and composition of the work highlight the harmonious simplicity of the flower and her work.

The work has strong vertical movement, consisting of a “U” shape that dominates the composition.

In the bottom third of the painting, we see blue, grey, and pink lines softly painted to separate the U-shape down the middle of the composition. The delicate blue line that separates the U-shape becomes a beautifully balanced element that pulls the eye through the work’s soft and harmonious composition.

Petunia No. 2 (1924)

| Artwork Title | Petunia No. 2 |

| Date | 1924 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size | 91.9 cm x 76.5 cm |

| Collection | Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe |

This work is one of O’Keeffe’s first truly large-scale paintings of flowers. The petunia flowers in the painting are vibrant, yet completely simplified. The focus of the work is on the flower’s color and form. Whilst O’Keeffe’s flower paintings were often viewed by critics to be symbolic of female sexuality, O’Keeffe insisted that the work was simply to illustrate the essence of nature and that it had no symbolic meaning beyond that.

In making this work, O’Keeffe said that her aim was to show people of New York to notice the things that she looks at.

The painting is a large-scale close-up rendition of the flowers that forces the audience to see the work in the same detail as she sees them. She said that busy New Yorkers did not take the time to examine the beauty of these small flowers and that her work is simply an image that portrays what she sees. She believed that by surprising the viewer by the scale of the work, she can make them take the time to truly look at it.

Radiator Building – Night, New York (1927)

| Artwork Title | Radiator Building – Night, New York |

| Date | 1927 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size | 121.9 cm x 76.2 cm |

| Collection | Fisk University, Nashville |

Radiator Building – Night, New York is a unique Georgia O’Keeffe artwork that shows her skill in capturing architectural buildings that are more rigid and refined when compared to the more natural themes in her work. The work shows New York City at nighttime and the painting is a combination of light and dark, structure and perspective.

The more organic shapes of the smoke on the right-hand side of the painting are the only reference to her more flowy shapes as in her nature-inspired paintings.

O’Keeffe found the city of New York claustrophobic and her low vantage point of the tall imposing buildings gives one the sense of being cased in. O’Keeffe’s New York City paintings have much more of a masculine feel to them and it is as if the artist is making a statement that she can make any work that she pleases and that her work should not be defined by gender.

Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue (1931)

| Artwork Title | Cow’s Skull, Red, White, and Blue |

| Date | 1931 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size | 101.3 cm x 91.1 cm |

| Collection | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

O’Keeffe’s work became highly influenced by the desert landscape during her visits to New Mexico. One of the things that started appearing frequently in O’Keeffe’s work during these visits was the sun-bleached skulls of animals. The painting, Cow’s Skull, Red, White, and Blue is one of these paintings. The painting has the skull of a cow at the center of the composition, with a red and a blue stripe on either side.

The red, white, and blue background of the work is a reference to the American flag and American nationalism.

The work celebrates the beauty of the desert and its large place within the American landscape. It is as if the artist is commenting on the irony that so many Americans don’t ever experience or visit these desert landscapes, even if it is such an integral part of the American continent and American identity.

From the Faraway, Nearby (1937)

| Artwork Title | From the Faraway, Nearby |

| Date | 1937 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size | 91.4 cm x 101.9 cm |

| Collection | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

O’Keeffe continued her work with skulls, and in 1935 her experiments with aspects of the landscape and bones became more abstract and adventurous. Some of her paintings during this time can almost be seen as inspired by Surrealism, as she combined these elements in the composition with strange perspective, sizing, and relative scale. The skull in this image, for instance, seems to be larger than the mountains of the desert itself. The use of color in the work is sensitive and mysterious, tying in with its poetic title.

The title of the work comes from the letters between O’Keeffe and Stieglitz during the times she spent away from him in Mexico.

For twenty years, O’Keeffe would travel between New Mexico, where she loved to paint, and New York, where Stieglitz was. Stieglitz, however, had never visited her in New Mexico. The letters that Stieglitz wrote to her whilst she was away, often contained phrases like “my faraway one” and “my faraway nearby one”. There is thus a sense that even though O’Keeffe was far away from Stieglitz, they were still connected.

The work, whilst communicating a sense of longing, also seems very powerful, communicated by the size of the skull, and can be reminiscent of O’Keeffe’s independence.

Red and Yellow Cliffs (1940)

| Artwork Title | Red and Yellow Cliffs |

| Date | 1940 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size | 61 cm x 91 cm |

| Collection | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

This landscape painting is a reference to the Chama River valley that was close to the first house that O’Keeffe purchased at Ghost Ranch in New Mexico. This is one of seven paintings that O’Keeffe painted of the same landscape. In this work, we see a similar color palette to her painting From the Faraway, Nearby.

The painting is composed of many beautiful shades of warm colors that give the landscape a comforting feel. The size of the mountains is accentuated by the tiny piece of blue sky that can be seen at the top of the painting.

Pelvis II (1944)

| Artwork Title | Pelvis II |

| Date | 1944 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size | 101.6 cm x 76.2 cm |

| Collection | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

From 1943, O’Keeffe’s paintings became more abstract again. Following the same process of zooming into the flowers and cropping out the edges, O’Keeffe applied the same process with her paintings of bones.

This work is one of a series of oil paintings that focuses on the curves and details of the animal bones that she found and collected in the desert.

In the negative spaces of the bones, we see a clear blue sky that gives one the illusion of holding the bones to your eyes as a kind of viewfinder by which to observe the world around you. This work is seen to be part of O’Keeffe’s Precisionism works, but the abstraction by cropping gives it almost a Surrealist or otherworldly feel.

Black Place, Grey and Pink (1949)

| Artwork Title | Black Place, Grey and Pink |

| Date | 1949 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size | 91.4 cm x 121.9 cm |

| Collection | Georgia O’Keeffe Museum |

Works like Black Place, Grey and Pink communicate to us something of O’Keeffe’s love for the New Mexican landscape. Like with her flower painting, this landscape painting is also stripped down to its elemental essence. There is a clear difference that can be seen here between her landscape paintings of the desert and her city paintings of New York.

One can almost feel this difference on an emotional level through O’Keefe’s compositional, perspective, and color choices.

Nothing about this work feels claustrophobic; rather, the work feels peaceful and quiet. O’Keeffe’s color choices in this work are a representation of the color ranges that she observed in the New Mexico landscapes and clouds during different times of the day and different seasons.

Sky Above Clouds IV (1965)

| Artwork Title | Sky Above Clouds IV |

| Date | 1965 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size | 2,44 m x 7,32 m |

| Collection | The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago |

Georgia O’Keefe’s paintings were always inspired by what she observed in her environment, and this is the same with her painting Sky Above Clouds IV. This painting is inspired by O’Keeffe’s travels around the world. When O’Keefe was in her 70s, she traveled by airplane for the first time and this painting is inspired by the view she saw when she was flying above the clouds. This painting is the last in a series of monumental paintings inspired by this view from the airplane window.

The style of the painting is rendered in her mature abstract style, with a new pattern-like element to it.

On such a large scale, the work becomes immersive and atmospheric, as if the viewer can step into the painting and walk on the clouds. This is one of O’Keeffe’s most celebrated paintings and is often spoken of in the same breath as the famous water lilies by Claude Monet. The work was to be exhibited for the first time at the San Francisco Museum of Art, but it was too large to fit through any of the museum’s entries.

Thereafter, the work was to be housed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, but it was eventually sent to the Art Institute of Chicago to keep in their collection.

O’Keeffe’s Final Years

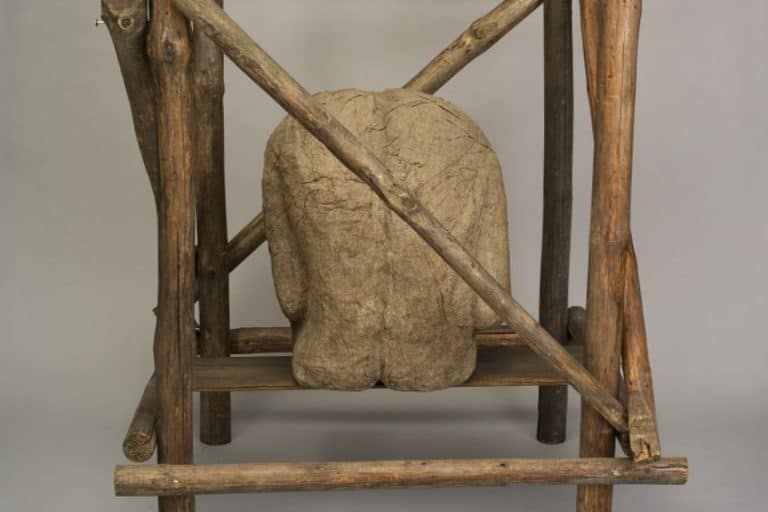

O’Keeffe’s health started depreciating by the mid-1970s. She suffered from muscle deterioration and her eyesight started to degenerate. Whilst the last two decades of O’Keeffe’s life were somewhat unproductive, she still created work along with some assistance. One of her friends, Juan Hamilton, assisted her in completing her autobiography in 1976. In 1977, Hamilton taught her how to work with the medium of clay that relied more on touch rather than sight. President Gerald Ford presented Georgia O’Keeffe with the Medal of Freedom in 1977, and in 1984, due to her deteriorating health, O’Keeffe moved to Sante Fe.

In 1985, O’Keeffe received the National Medal of Arts and a year later, on March 6, 1986, Georgia O’Keeffe passed away in Santa Fe, New Mexico. O’Keeffe’s ashes were scattered over the landscape of Cerro Pedernal, a place that she loved and that she painted many times during her life. A museum was opened in Georgia O’Keeffe’s name in Sante Fe to honor and protect her life’s work.

The museum, called the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, hosts walkabouts and talks about her work, and gives guided tours of her studio and home, which is now a national historic landmark.

Book Recommendations

There are so many books on the life and work of Georgia O’Keefe that it can be a daunting task to choose where to start a collection. If you are interested in learning more about the work and life of Georgia O’Keeffe, we recommend starting with these marvelous publications:

Portrait of an Artist: A Biography of Georgia O’Keeffe (1997) by Laurie Lisle

This book is the first full account of the life of Georgia O’Keeffe. Portrait of an Artist is an in-depth exploration of Georgia O’Keeffe’s life from childhood to the controversial teacher, to the lover of Stieglitz, and finally, to the pioneering and avant-garde artist. The book is comprised of over three year’s dedicated research and includes recollections of over 100 of Georgia O’Keefe’s friends, family, colleagues, and neighbors. The book also includes previously unpublished letters written by the artist to help paint the portrait of the remarkable life of Georgia O’Keeffe.

- The first definitive account of the legendary American painter

- The story of the romance between the artist and her older mentor

- Exploring the dazzling career of this famous female Modern artist

Georgia O’Keeffe and New Mexico: A Sense of Place (2004) by Barbara Buhler Lynes, Lesley Poling-Kempes, et.al.

O’Keeffe visited New Mexico for the first time in 1917. She fell in love with the stark desert landscape and unique architecture of the place, which continued to inspire her throughout her life. This is the first book published that analyses the many Georgia O’Keeffe paintings that are inspired by the New Mexico landscape. The book is truly beautifully illustrated and elegantly written. It shows 50 paintings of O’Keeffe along with striking photographs of the landscape that inspired them. The book also includes beautiful essays of O’Keeffe’s work and life in the desert landscape, along with interesting geological explanations of how these truly extraordinary landscapes were formed.

- The first book to analyze O'Keeffe's famous depictions of New Mexico

- Reproduces the accompanying exhibition's paintings and photos

- Beautifully illustrated and gracefully written

Georgia O’Keeffe: Watercolors (2016) by Georgia O’Keefe and Amy von Lintel

This book is a catalog of one of the first major exhibitions of Georgia O’Keeffe that includes nearly 50 watercolors that the artist created between 1916 and 1918. O’Keefe’s watercolors are a testament to the artist’s turn towards complete abstraction and they cover the most innovative years for the artist as she discovers her own way of creating. The paintings are inspired by the Texan landscape, as well as O’Keeffe’s own body. The beauty and sensitivity of these works can really be appreciated through the multiple large full-scale and full-color reproductions that are so generously published in this book.

Throughout the decades, O’Keeffe remained to be one of the most celebrated American Modernist painters. Throughout her long career, Georgia O’Keeffe consistently showed the world her unique personal touch and the sensitivity by which she admires natural landscapes. Although O’Keeffe’s career was heavily supported by the influential Alfred Stieglitz, she consistently prioritized her independence and originality. Georgia O’Keeffe’s work was a testament that female artists’ work is just as important as that of men’s work and that indigenous American landscapes are just as significant as man-made cities. Georgia O’Keeffe fought against critics’ gendered and sexualized readings of her work and in so doing, she established a new place for female artists in the American art scene. Her work and life continue to be a source of great inspiration for all female artists who love her work.

Frequently Asked Questions

When Did Georgia O’Keeffe Die?

When did Georgia O’Keeffe die? This is a question many people ask, but not many ask what the conditions around O’Keeffe’s last moments were. O’Keeffe passed away on the 6th of March 1986. She was 98 years old when she passed away and she did so in a place that she dearly loved: Santa Fe, New Mexico. O’Keeffe was suffering from failing vision and macular degeneration in her last years and she created her last painting, without assistance, in 1972. She did, however, still paint past this date and did not allow her degenerating eyesight to stop her, as she believed that her imagination and her spirit is all she needs to create art. O’Keeffe then hired assistants to help her in creating works during her last years on earth.

What Makes Georgia O’Keeffe’s Art Unique?

Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings were unique in that her kind of abstraction did not yet exist in America at the time. O’Keefe masterfully used the elements of line, color, and composition to create works that were seen as some of the first purely abstract works. O’Keefe was also a master of color and created bold and vibrant works that were simultaneously strong and sensitive.

How Many Paintings Did Georgia O’Keeffe Paint?

We cannot know exactly how many artworks Georgia O’Keeffe created over her life. It is impossible to know for certain how many works the artist made that might not be well documented, for instance, work that she made and gave as gifts, or works that never left her studio that she might have decided to disregard. Simply from looking at the works that are well-documented, it has been established that O’Keeffe created more than 2,000 paintings, approximately 200 of which were of flowers.

Chrisél Attewell (b. 1994) is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. Her work is research-driven and experimental. Inspired by current socio-ecological concerns, Attewell’s work explores the nuances in people’s connection to the Earth, to other species, and to each other. She works with various mediums, including installation, sculpture, photography, and painting, and prefers natural materials, such as hemp canvas, oil paint, glass, clay, and stone.

She received her BAFA (Fine Arts, Cum Laude) from the University of Pretoria in 2016 and is currently pursuing her MA in Visual Arts at the University of Johannesburg. Her work has been represented locally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, residencies, and art fairs. Attewell was selected as a Sasol New Signatures finalist (2016, 2017) and a Top 100 finalist for the ABSA L’Atelier (2018). Attewell was selected as a 2018 recipient of the Young Female Residency Award, founded by Benon Lutaaya.

Her work was showcased at the 2019 and 2022 Contemporary Istanbul with Berman Contemporary and her latest solo exhibition, titled Sociogenesis: Resilience under Fire, curated by Els van Mourik, was exhibited in 2020 at Berman Contemporary in Johannesburg. Attewell also exhibited at the main section of the 2022 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Learn more about Chrisél Attwell and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Chrisél, Attewell, “Georgia O’Keeffe – Mother of Modern Feminist Art.” Art in Context. March 23, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/georgia-okeeffe/

Attewell, C. (2022, 23 March). Georgia O’Keeffe – Mother of Modern Feminist Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/georgia-okeeffe/

Attewell, Chrisél. “Georgia O’Keeffe – Mother of Modern Feminist Art.” Art in Context, March 23, 2022. https://artincontext.org/georgia-okeeffe/.