Georges Braque – Explore the Cubism Artworks by This French Artist

French artist Georges Braque was a pioneer of Cubism, a groundbreaking art movement. Georges Braque’s paintings centered on still lifes and ways of perceiving items from differing viewpoints using line, color, and texture all through his life. George Braque’s Cubism style can be observed in his works such as Violin and Candlestick (1910) and Houses at Estaque (1908). Today we will be exploring Georges Braque’s biography as well as his most renowned artworks.

Table of Contents

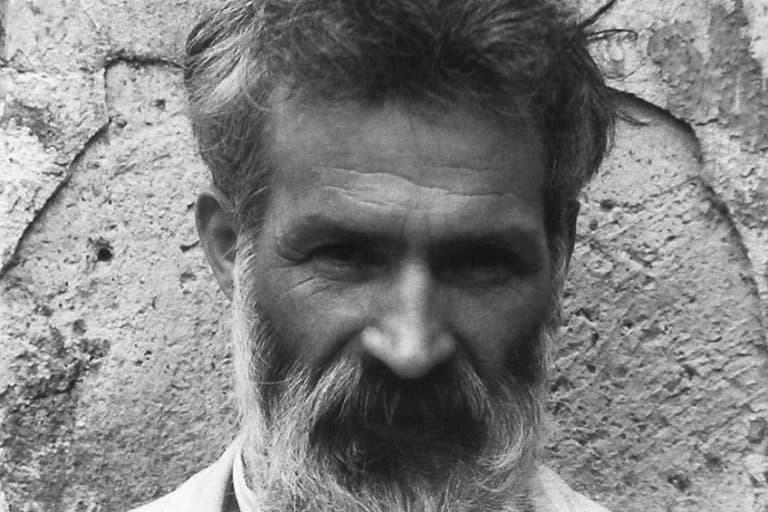

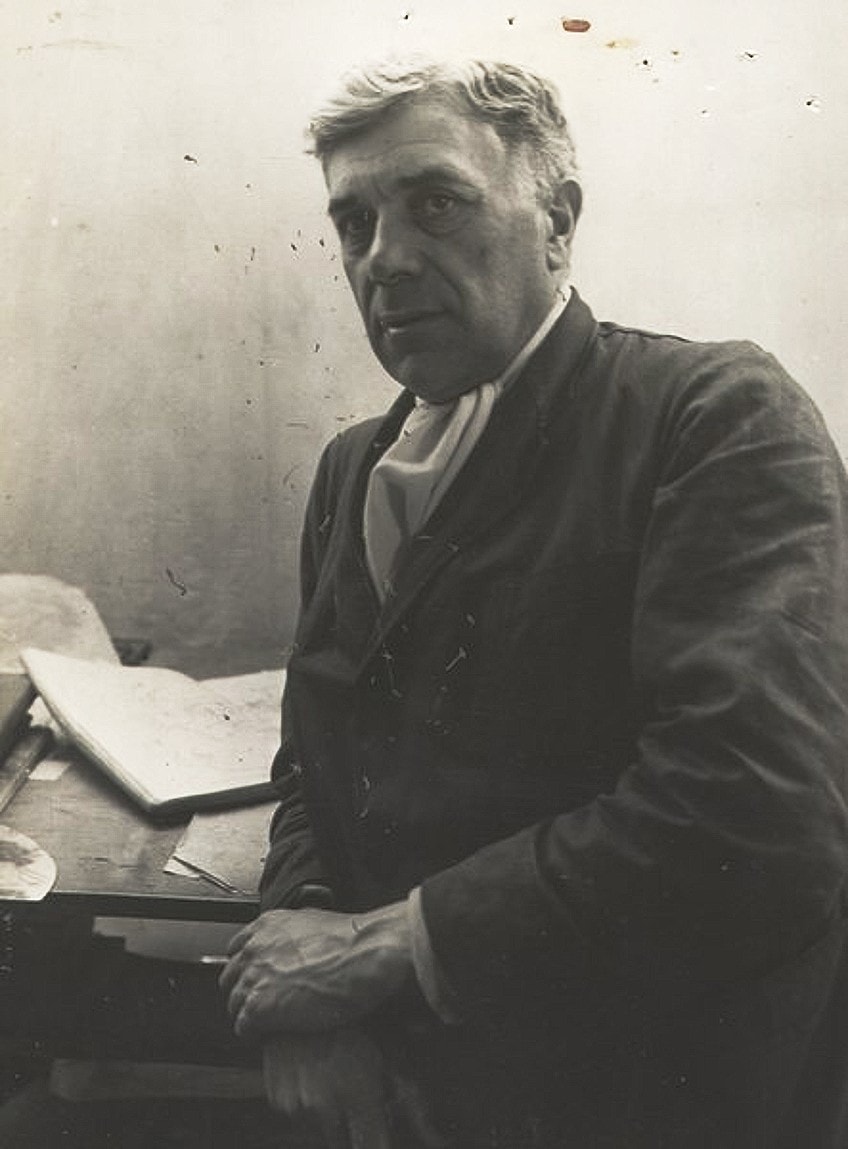

George Braque’s Biography

| Nationality | French |

| Date of Birth | 13 May 1882 |

| Date of Death | 31 August 1963 |

| Place of Birth | Argenteuil, France |

Even though George Braque started as a representative of the Fauvism movement, it would not be until he encountered Pablo Picasso that he actually began to create with a Cubist aesthetic. Whereas their works of art had many commonalities in the palette, fashion, and source material, Braque asserted that his practice, unlike Picasso’s, was “bereft of iconological critique” and was involved solely with visual space and structure.

In his creations, Braque pursued harmony and balance, particularly through papier collés, a cut and pasted paper collage method invented by Braque and Picasso in 1912.

Braque took collage to an even higher level by bonding cut-up adverts into his works of art. This foreshadowed modern art movements involved with media critique, for example, Pop art. To accomplish higher tiers of dimension in his works of art, Braque etched letters onto them, mixed hues with sand, and replicated wood grain and marble.

His still-life paintings are so conceptual that they border on becoming shapes that convey the essential nature of the objects seen rather than specific portrayals.

Childhood

Georges Braque was encouraged to use imaginative painting methods from a young age. His father ran a decorative painting company, and Braque’s curiosity about texture and tactile feedback may have stemmed from his time operating as a decorator for him. At the age of 17, Braque moved from Argenteuil to Paris with friends Raoul Dufy and Othon Friesz in 1899.

He trained with an interior designer in Paris and in 1902 he received his certificate.

Early Training

Braque’s first works were in the Fauvist fashion. From 1902 to 1905, after quitting his job as an interior designer to explore painting full-time, he experimented with Fauvist concepts and collaborated with Henri Matisse. He held his very first art show at the Salon des Indépendants in 1906, where he showcased his brightly colored Fauvist creations.

Nevertheless, a trip to Pablo Picasso’s workshop in 1907 to see Picasso’s groundbreaking work, Les “Demoiselles d’Avignon”, had a profound effect on him. Following their meeting, the two artists formed a friendship and artistic companionship.

“We would meet every day to debate and test the concepts that were beginning to form, and to make comparisons of our various creations,” Braque explained. Picasso is directly responsible for the dramatic shift in Braque’s style of painting. Braque aimed to bolster “the positive and productive components in his creations while forsaking the expressionistic extremes of Fauvism” once he grasped Picasso’s goals.

Louis Vauxcelles, a French art critic, coined the term Cubism after defining Georges Braque’s paintings as “bizarreries cubiques.”

During this pre-war, productive period, Braque (along with Picasso) made significant advances to modern art, especially through their investigation of Cubism – through the movement’s Analytic and Synthetic phases.

Mature Period

Picasso and French artist Braque collaborated until Braque’s return from the war in 1914. When Picasso started to paint figuratively, Braque felt his companion had disrespected their Cubist processes and guidelines, and he went his own way. He was, nevertheless, impacted by Picasso’s works, notably papier collés, a montage approach invented by both creatives in which only pasted paper is used.

His collages were filled with geometric shapes that were broken up by musical instruments, fruit, or furniture. These sculptures were so three-dimensional that they are considered crucial in the development of Cubist sculpture.

Braque had depleted his papier collés experiments by 1918 and had returned to painting still lives. Audiences started to notice a much more limited palette in Braque’s first postwar solo exhibition in 1919. Nonetheless, he firmly adhered to Cubist rules regarding the depiction of objects from differing viewpoints in geometrically patterned forms.

In this regard, he remained a true Cubist for a longer period of time than Picasso, whose aesthetic, subject matter and color palette changed on a regular basis.

Braque was most interested in demonstrating how objects appear when viewed in various temporal areas and visual planes over time. Throughout the 1920s, he gravitated toward producing sets and costumes for theater and dancing performances as a result of his dedication to depicting space in multiple ways.

Late Years and Death

In 1929, Braque returned to landscape painting, this time using new, bright colors inspired by Matisse and Picasso. Then, in the 1930s, Braque started to depict Greek heroes and gods, claiming that the subjects had been detached from their symbolism and should be viewed solely through a formal lens. He dubbed these artworks “exercises in calligraphy,” conceivably because they were less concerned with figures and more with sheer line and shape.

During the latter half of the 1930s, Braque started creating his Vanitas sequence, in which he pondered suffering and death from an introspective point of view.

He became progressively fixated with the physicality of his works of art, experimenting with different brush strokes and paint qualities to augment his subject matter. The objects in his still lifes were very personal to Braque, but he never revealed their meanings. Skulls, for instance, were objects he painted regularly at the start of World War II.

When World War II ended in 1944, Braque began to focus on lighter subjects such as billiard tables, flowers, and garden seats. His final series of eight canvases completed between 1948 and 1955, featured illustrations that symbolized the artist’s deepest feelings on each item rather than external references. Close to the end of his life, Braque depicted birds regularly as a perfect depiction of his fixation with the environment and movement.

Braque is recognized as a forefather of Cubism, whose still life paintings were both rational and sensual.

In this context, he was a classic painter who impacted artists such as Wayne Thiebaud and Jim Dine, who specialized in still life painting. He was also an accomplished colorist, and his impact can be seen in the work of contemporary artists who use color in similar ways. Perhaps Braque is best known for his use of collage, which is used by many modern artists, from artists like Mark Bradford to sculptors like Jessica Stockholder, to comment directly on culture and its commodities.

George Braque’s Cubism Style

Braque’s 1908 to 1912 works of art mirrored his newfound interest in geometry and concurrent perspective. He initiated a study of the effects of illumination and perspective, as well as the means that artists use to portray these effects, appearing to call into question the most basic of artistic norms. In his rural images, for instance, Braque regularly whittled down an architectural style to a geometric form resembling a cube while rendering its shading in such a way that it appeared both flat and three-dimensional by fracturing the image. This is depicted in the painting Houses at Estaque (1908).

Starting in 1909, he started to collaborate closely with Picasso, who was working to develop a comparable proto-Cubist style.

Pablo Picasso was impacted by Gauguin, Cézanne, African masks, and Iberian sculpting at the time, whereas Braque was primarily interested in improving Cézanne’s concepts of differing viewpoints. A comparative study of Picasso’s and Braque’s creations from 1908 reveals that his meeting with Picasso accelerated and intensified Braque’s investigation of Cézanne’s concepts rather than diverting his thinking in any significant way.

The phrase ‘Cubism’ quickly became popular, but Picasso and Braque were slow to embrace it.

Cubism, according to art historian Ernst Gombrich, was the most drastic attempt to eliminate ambiguity and impose one interpretation of the image of a man-made construction, a colored canvas. The Cubist aesthetic spread rapidly throughout Paris and then Europe. Even though Braque started his career creating landscapes, he and Picasso realized the value of painting still lifes in 1908.

Braque clarified that he started to focus on still lifes because they have a tactile, he may perhaps say manual space. This satisfied his desire to touch things rather than just look at them. In tactile space, you calculate the length between yourself and the object, while in visual space, you calculate the distance between things. This is what drew me from landscape to still-life so long ago.” Still life was also more viewable in terms of point of view than a landscape, allowing the painter to see the object from various angles. During the 1930s, Braque’s early involvement in still lifes was reignited.

During the interwar period, Braque displayed a liberalized, more laid-back style of Cubism, emphasizing color and a softer rendering of items. He stayed, nevertheless, dedicated to the cubist technique of concurrent perspective and segmentation.

Unlike Pablo Picasso, who was constantly reinventing his painting technique, generating both representational and cubist visuals and integrating surreal concepts into his works, Braque stayed true to the Cubist aesthetic, creating illuminated, otherworldly still life and figure configurations. By the time he died in 1963, he was deemed as one of the School of Paris’s and modern art’s elder statesmen.

Georges Braque’s Paintings

Braque presumed that an artist experiences perfection in terms of volume, line, weight, and bulk and that he perceives his subjective perception through that beauty. He characterized objects that had been fractured into fragments as a method of getting closer to the object. Fragmentation aided me in establishing space and motion in space. He chose a monochromatic and neutral palette with the intention that it would draw the viewer’s attention to the subject matter.

Houses at Estaque (1908)

| Date Completed | 1908 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 40 cm x 32 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Art, Berne |

This Braque artwork was rejected in 1908 from the Salon d’Automne. Henri Matisse informed Louis Vauxcelles at that period, “Braque has just submitted a work of art produced of little cubes.” Matisse’s words were relayed by critic Charles Morice, who also mentioned Braque’s little cubes.

The theme of the viaduct at l’Estaque had influenced Braque to create three works of art characterized by form simplicity and viewpoint deconstruction. The paintings created by Braque during the summer of 1908 at l’Estaque are regarded as the first Cubist paintings.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lZ6Wta0ru6Q&t=6s

After being rejected by the Salon d’Automne, they were fortunate enough to be shown at Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler’s Paris gallery that autumn. These simple landscape works of art demonstrated Braque’s commitment to dissecting visuals. It is a Proto-Cubist artwork in which Cézannian trees and houses are illustrated without any single unified perspective.

Even so, houses in the background look smaller than others in the foreground, which is uniform with the classical perspective. Apollinaire notes nothing about the works of art on display, but does mention “the synthesized motifs he likes to paint” and that he “no longer needs to give anything to his environment.”

Braque was described by Vauxcelles as a bold man who disdains form, “reducing everything, locations and figures and houses, to dimensional schemas, to cubes.”

Violin and Candlestick (1910)

| Date Completed | 1910 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 60 cm x 50 cm |

| Current Location | San Francisco Museum of Modern Art |

Analytic Cubism, a groundbreaking artistic aesthetic spearheaded by Georges Braque and Picasso to portray three-dimensional artifacts on a flattened surface without the use of conventional Renaissance perspective, is embodied in this work. Interpreted forms are subdivided, fragmented, squashed, and then recreated in different perspectives within a superficial space in this theoretical approach to painting. This type of fragmentation, according to Braque, is a method of getting nearer to the object.

Georges’ fascination for form and consistency resulted in “Violin and Candlestick”, which was motivated by a desire to give the viewer the impression of being able to move freely within the artwork.

To accomplish this, the painter armatured the subjects in the center of a grid and used earth-toned colors to cover the black-outlined objects’ boundaries. By doing so, he was capable of transforming static volumes into compound surfaces held on a flat plane, allowing spectators to enjoy more of the form than from any other angle.

Recognizing and comprehending the effects of light deftly in order to evoke the adequate emotional responses and effects of the subjects was also a critical parameter in Braque’s “Violin and Candlestick”.

Still-life props (some distinguishable, some not) are grouped toward the middle of a grid-like armature in this piece. By opening up and covering over the limits of the black-outlined items, and by utilizing the same earth-toned colors throughout the painting, Braque brought the objects and the background together. He reshaped the volumes in the still life to fit their numerous surfaces on a flat plane, enabling the audience to perceive more of the form than would be feasible from a single point of view.

The Portuguese (1911)

| Date Completed | 1911 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 116 cm x 81 cm |

| Current Location | Kuntsmuseum, Basel |

The Portuguese represent an interesting turning point in the evolution of Braque’s paintings. He emblazoned the letters “D BAL” and roman numerals on the upper right side. Even though he would include letters and numbers in a still life in 1910, they were a truly representative component of the painting. The numbers and letters are solely a stylistic inclusion in this piece.

Braque’s intentions for adding the letters are varied, but the majority of them were to draw the viewer’s attention to the canvas itself.

The canvas in representational paintings serves only as a substratum to hold whatever impression the painter desires. By incorporating numbers, out-of-context components, and texture, the audience is made aware that the painting can also hold external elements, attempting to make the surface of the artwork just as crucial as what is placed on top of it.

Clarinet and Bottle of Rum on the Mantlepiece (1911)

| Date Completed | 1911 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 81 cm x 60 cm |

| Current Location | Tate Museum, UK |

The work depicts a diverse range of geometric shapes overlaid to form the right-angled silhouette of a mantelpiece as seen from various perspectives. The artwork’s vivid title draws the audience’s eye to the objects displayed in the piece, and the perception of intoxication affiliated with the rum bottle, represented by the letters “RHU”, serves to reflect the disorienting encounter of viewing it. This composition clearly demonstrates Braque’s interest in musical themes.

Furthermore, the headstock of a cello can be seen at the bottom-right of the piece, along with a sprinkling of shapes that look similar to musical notes and treble and bass clefs.

Braque’s body of work from 1908 to 1912 looks very similar to that of his more renowned Pablo Picasso, and this specific aspect was painted while the painter was vacationing with Picasso in the French Pyrenees.

This artwork features an arrangement with many characteristics associated with the Cubism movement that Braque and his colleagues initiated.

Bottles and Fishes (1912)

| Date Completed | 1912 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 61 cm x 75 cm |

| Current Location | Tate Museum, UK |

Throughout his art career, Braque represented both bottles and fishes, and these objects serve as distinguishing features between his various styles. Bottles and Fishes is a great instance of Georges Braque’s explorations into Analytic Cubism while collaborating with Picasso.

The restricted distinctive earth tone palette in this painting renders nearly imperceptible objects as they crumble along the horizontal plane. Although one can still observe diagonal lines, Braque’s early works were mostly vertical or horizontal in nature.

Recommended Reading

Today we discovered more about George Braque’s biography, as well as the French artist’s artworks. However, perhaps you would like to learn even more about George Braque’s Cubism style. Here is a list of suitable reading material to help you do just that.

G. Braque (1971) by Francis Ponge

This investigation of Braque’s career includes magnificent reproductions as well as insightful historical and aesthetic analyses of his work before and during World War II. This book is the first in-depth look at Braque’s experimentations with still lifes and interior decoration during a pivotal but often overlooked period in his career. Braque, a key figure in the development of Cubism, used the genre of still life to undertake lifelong research into the essence of impression through the haptic and fleeting world of everyday objects.

- Investigates Braque's entire oeuvre

- An in-depth look at the artist's experimentations

- Includes a look at his interior decoration phase

Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life (2013) by Karen K. Butler

This collection deems Braque’s works of art within the political and cultural sense of Europe at the time, evaluating a transitional period between his early Cubist creations and his late grand series. Braque’s works of art are replicated in brilliant color and supplemented by historical essays that examine the emergence of the French artist’s fame in America, as well as his first major solo exhibition, the arrival of his early 1930s and 1940s work, and a behind-the-scenes look at the artist’s materials and process as activated by a focused preservation investigation of select major works.

- Artworks reproduced in vivid color

- Works accompanied by scholarly essays

- An examination of Braque's entire career

Georges Braque was a French artist, and collagist, in the 20th century. His most significant contributions were his 1905 alliance with Fauvism and his involvement in the advancement of Cubism. Between 1908 and 1912, Braque’s work was frequently affiliated with that of his peer Pablo Picasso. For many years, their Cubist efforts were impossible to distinguish, but the quiet existence of Braque was temporarily eclipsed by Picasso’s fame and recognition.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Georges Braque?

Georges Braque, a French artist, was a founder of Cubism, a groundbreaking art movement. Throughout his life, Georges Braque’s paintings focused on still lifes and various ways of perceiving objects using line, color, and texture. In works like Violin and Candlestick (1910) and Houses at Estaque (1908), George Braque’s Cubism style can be seen.

What Is Cubism?

The term Cubism became popular quickly, but Picasso and Braque were slow to accept it. Cubism was the most extreme attempt to remove ambiguity and impose a single interpretation of a man-made structure, a colored canvas. The Cubist aesthetic quickly spread across Paris and then Europe. Despite the fact that Braque began his career painting landscapes, he and Picasso realized the importance of painting still lives in 1908.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Georges Braque – Explore the Cubism Artworks by This French Artist.” Art in Context. May 21, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/georges-braque/

Meyer, I. (2022, 21 May). Georges Braque – Explore the Cubism Artworks by This French Artist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/georges-braque/

Meyer, Isabella. “Georges Braque – Explore the Cubism Artworks by This French Artist.” Art in Context, May 21, 2022. https://artincontext.org/georges-braque/.