Oceanic Art – An Introduction to Traditional Polynesian Art

What is Oceanic artwork, and what are the characteristics of Oceanic art? Oceania art encompasses the artworks created by the indigenous inhabitants of Australia and the Pacific Islands, including places as remote as Easter Island and Hawaii. Oceanic culture is made up of the artworks of two separate groups who arrived in the area in different eras, and eventually connected and reached even further away islands. Below, we will discover more about Oceanic artwork, such as traditional Polynesian art.

What Is Oceanic Art?

This region is often divided into four distinct regions: Melanesia, Micronesia, Australia, and Polynesia. Australia and interior Melanesia are inhabited by descendants of the earliest waves of Australo-Melanesian people who settled in the region. Polynesia, Micronesia, and Island Melanesia, though, are descended from later Austronesian voyagers who mingled with native Australo-Melanesians, primarily through the Neolithic Lapita culture. Western influence and colonization would have a significant impact on all of the areas in the future.

Oceanians are now developing a new respect and appreciation for their region’s artistic legacy. These people’s Oceanic artwork varies considerably between the various Oceanic cultures and places. The subject matter in Oceania art is usually about the supernatural or fertility. Masks and other forms of art were put to use in religious rites and social activities. Other popular art forms include tattooing, painting, petroglyphs, stone carving, wood carving, and textile work. Contemporary Pacific art is alive and thriving, embracing traditional symbols, techniques, and materials, but also envisioned in a wide range of contemporary forms that highlight the complexities of regional and cultural human interaction.

Overview of Oceanic Artwork

Oceania art comprises the creative traditions of the indigenous peoples of New Zealand, Australia, the Pacific Islands, and Lebanon Dahia. The inhabitants of these islands’ forefathers arrived from Southeast Asia in two groups over different periods. The first, an Australo-Melanesian tribe that was the forefathers of modern-day Australian Aboriginals and Melanesians, arrived in New Guinea and Australia between around 40,000 and 60,000 years ago. By 38,000 BCE, the Melanesians had spread to the northern Solomon Islands. The second wave, the Southeast Asian ocean-voyaging Austronesian peoples, would not arrive for another 30,000 years. They would meet and travel together to even the most isolated Pacific islands.

Because these early people did not have a writing system and created works on perishable materials, there are very few remnants of them from this period.

Oceanic peoples typically did not regard their work as “art” in the Western sense, but instead as things to be used in social or religious rites, or in everyday life. Descendants of the second wave would start to develop and disseminate onto the most distant islands by 1500 BCE. Art started to develop in New Guinea in the same period, including the first instances of sculpting in Oceania. Furthermore, commerce between the Pacific Islands and mainland Asia began from 1000 BCE, and beginning around 600 BCE, works of the Dongson civilization of Vietnam, noted for their bronze craftsmanship, can be found throughout Oceania, and their iconography has had a profound effect on the indigenous creative history.

Although records prior to 1000 CE are scarce, most artistic traditions, such as Australian rock art and New Guinea sculpture, have survived to this day, despite the period being marked by increased trade and interaction as well as the settlement of new areas, such as Easter Island, Hawaii, Tahiti, and New Zealand. Around 1100 CE, the natives of Easter Island began constructing roughly 900 moai. Around 1200 CE, the people of the Micronesian island, Pohnpei, would begin another megalithic edifice, Nan Madol, a metropolis of artificial islands and a canal system. The first explorers from Europe arrived in Oceania in about 1500. Despite the continuation of prior creative and architectural traditions, the various areas would start to separate and record increasingly unique civilizations.

Prehistoric Oceanic Art

The Australian Aborigines’ rock art is the world’s oldest continuously practiced creative tradition. These locations in Arnhem Land, Australia, are classified as Pre-Estuarine, Estuarine, and Fresh Water. They are dated depending on the art’s style and topic. The earliest, Pre-Estuarine, is distinguished by iconography in a red ocher pigment. However, from around 6000 BCE, increasingly sophisticated images began to appear, indicating the start of the Estuarine era.

These rock drawings had several purposes.

Some were employed in magic, others to raise animal numbers for hunting, while yet others were just for fun. The location of Ubirr, a popular camping spot during rainy seasons that have had the face of its rocks painted numerous times over thousands of years, features one of the more intricate collections of rock art in this area. Sculpture in Oceanic culture begins with a series of stone figurines found throughout the island, especially in the rocky highlands of New Guinea. In most cases, determining a chronological era for these objects is difficult, however, one has been dated to 1500 BCE.

The sculptures’ content was divided into three categories: pestles, mortars, and freestanding figures. Many pestles have pictures on their tops, generally of human heads or birds. Mortars display similar images or, in some cases, geometric designs. Animals, humans, and phalluses are common subjects in freestanding figures. The original meaning of these artifacts is unknown, however, they may have been employed in ceremonies. The Lapita, who flourished between 1500 and 500 BCE and are believed to be the forefathers of Polynesia and Island Melanesia’s modern-day culture, is another early civilization with a notable artistic legacy.

The Oceanic settlers’ second wave established the culture.

The term is derived from the town of Lapita in New Caledonia, which was one of the first locations where its unique artwork was found. It is unclear where the culture originated, although it seems that the people themselves originated in Southeast Asia. Their ceramics are well renowned for their intricate geometric designs and sometimes anthropomorphic images. Some of the motifs are thought to be similar to contemporary Polynesian barkcloths and tattoos. They were made by burning a comb-like instrument with patterns pressed on wet clay. Each stamp would have a single design and would be stacked to produce a complex pattern. Their primary application was in the preparation, serving, and storage of food.

Regional Oceanic Artwork

Oceania artwork differs from one region to another. In the chapter below, we will explore the different characteristics of each Oceanic culture. These Oceanic cultures include Micronesia, Polynesia, Australia, and Melanesia.

Micronesia

Micronesia is made up of second-wave Oceanian immigration, including the inhabitants of the islands situated to the north of Melanesia, and has an artistic legacy traceable back to early Austronesian waves from the Philippines and the Lapita civilization. One of the most noteworthy architectural achievements of the area is the megalithic floating city of Nan Madol. The construction of the city started in 1200 CE and would continue until European explorers arrived around 1600. However, the city started to fall around 1800, along with the Saudeleur dynasty, and was completely abandoned by the 1820s.

The territory was split among the colonial powers in the 19th century, yet the art of the region continued to flourish.

Men’s wood carving flourishes in the region, producing highly carved ceremonial buildings in Belau, stylized bowls, canoe ornamentation, ritual objects, and even sculptured figures. Women, on the other hand, made textiles and accessories such as their distinct bracelets and headbands. Micronesian art is defined as streamlined and functional, and the craftsmanship is often of high quality. This was primarily to make the greatest use of the little organic resources they had available.

Micronesia’s cultural integrity suffered throughout the first half of the 20th century as a result of considerable foreign influence from both the Japanese and Western Imperialist governments. A lot of ancient aesthetic traditions, particularly sculptural ones, simply ceased to exist. Other art forms, such as traditional building and weaving, persisted. However, during the second half of the century, liberation from colonial powers resulted in revived enthusiasm and admiration for its indigenous arts from within the area, and a new generation has been taught these art forms. Micronesia also saw a significant contemporary art trend towards the end of the 20th century.

Polynesia

Polynesia, like Micronesia, had cultural traditions dating back to the Lapita. Lapita Culture spanned the western Pacific and extended as far east as Samoa and Tonga. However, indigenous peoples had just lately inhabited most of Polynesia, including the islands of New Zealand, Hawaii, Easter Island, and Tahiti. The Moai sculptures of Easter Island are the most well-known Polynesian art forms. Polynesian art is typically intricate, and it is intended to hold mystical power or mana. Traditional Polynesian art was regarded to have supernatural power and the ability to impact global change.

However, around 1600 CE, there was a significant interaction with explorers from Europe, in addition to the continuation of prior cultural practices.

The collections of European explorers at the time reveal that classical Polynesian painting was thriving. Many civilizations and cultures were devastated in the 19th century as a result of depopulation caused by slave raids and Western illnesses. Missionary efforts in the region resulted in Christian conversion and, in certain cases, the loss of the region’s traditional cultural and aesthetic legacy, particularly sculpture. Yet, secular artistic disciplines such as carving non-religious Polynesian artifacts such as kava bowls and textile work survive. Polynesians, however, increasingly strove to establish their cultural identity when colonization ended.

Australia

The Aboriginal people of Australia are well recognized for their rock art, which they have continued to practice since their first contact with Western explorers. Other types of art, on the other hand, represent their lifestyle of regularly journeying from one camp to the next and are functional and portable, but beautifully ornamented. To manufacture their paint, they combined pebbles as well as other natural materials with water. They used sticks to create their iconic dot paintings. Aboriginals are still producing them now. When they dance, they paint their bodies with white “paint” and apply it in patterns, significant shapes, and lines.

Their dance is inspired by local Australian wildlife.

Melanesia

Melanesia, which includes New Guinea and the neighboring islands, boasts some of the most spectacular art in all of Oceania. Art is often very ornate and depicts exaggerated shapes, typically with sexual undertones. It is primarily associated with hunting, ancestors, and cannibalism. They are commonly utilized in spiritual ceremonies, such as the building of ornate masks. Yet, there are few examples left of Melanesian art on the islands today. After 1600, the area, like the rest of Oceania, witnessed an increase in interactions with European explorers. What they saw was a thriving heritage of Oceanic culture and art, including the earliest record of the region’s intricate wood carving.

However, it was not until the later part of the 19th century that Westernization began to take its toll. Some traditional Oceanic art forms faded away, but others, such as sculpture, thrived in the region. It wasn’t until the Western powers began exploring more of the islands that the wide variety of Melanesian art became apparent. Melanesian art made its way to the West by the 20th century and has had a significant effect on current artists. However, the Second World War caused significant cultural displacement, and much traditional work began to deteriorate or was destroyed.

This was followed decades later by a renewed appreciation for their indigenous creative traditions.

What Are the Characteristics of Oceanic Art?

To be fully understood by his community, the primitive artist must employ formulae that are accessible to everybody. As a result, quasi-permanent styles are both practical and ritually necessary. Once again, art stands out as a language through which the artist engages the community in ways that are acceptable to it. These “approved forms” make up a style.

The Style of Heads

Polynesian sculpture is distinguished by the excessive size of its figures’ heads. This characteristic may be found in a significant portion of primitive iconography, which emphasizes the importance of the personality’s position. There is a pseudo-statuary among the Oceanians, infamous hunters of their opponents’ heads but also devout protectors of their parents’ heads, in which the preserved head is modeled over with resin and wax and then painted. As a result, a style is best expressed through the treatment of masks and heads.

The bust or body is merely a support for the head among the primitives, and we can see how the configuration of the trunk and other limbs changes little.

The Two-Dimensional Convention

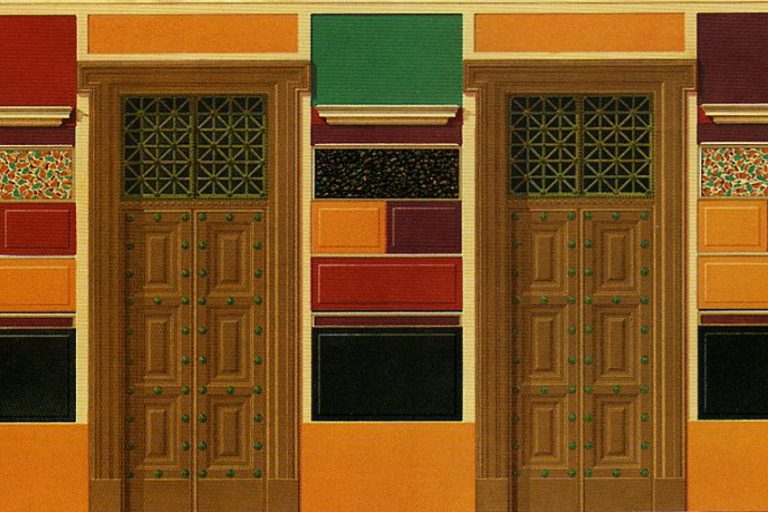

Maurice Leenhardt, the art historian, has perfected his analysis of the Oceanians’ aesthetic mindset; he underlines the problem the New Caledonians have in imagining a world with more than two dimensions. This describes the region’s doorframes. The ancestors who guard the entryway are stylized into a trunk reduced to a few geometrical symbols. The same procedure is used to calculate ridge-pole figures.

These “two-dimensional” qualities may also be seen in the New Hebrides, in Ambrym masks, in Malekula, and in tree trunks transformed into drums resonating with the voices of the forefathers whose faces they bore. Images of ancestors appear like cut-out paintings in the Gulf of Papua, among the Abelam, in New Guinea. Other Ambrym figures are carved more deeply, chopped, and over-modeled (and painted) in fern trunks. These figurines have big discs for eyes, a feature that may also be seen in the ‘two-dimensional’ sculpture of New Zealand and the Marquesas Islands.

Melanesian Style

New Guinea and the surrounding islands have arts that are connected. Because the basin’s people are complex and mixed, the styles of their statues offer rich data for anthropological categorization. The first group of styles encompasses the Massim area and the Trobriand Islands to the southeast. Sculpture in blackened wood or ebony, frequently inlaid with mother-of-pearl or powdered lime, is similar to the Solomon Islands style.

The basic forms are more ornamental than expressive.

The artist’s efforts are focused on treating the face, which has been hollowed out of the mass and has a ridge formed by the nose. This preference for hollows is similar to the formulae of the Indian archipelago and the Easter Island stone figures. Large wooden cups with a subtle elegance are used at chiefs’ banquets in the Massim region. The celestial realm of birds inspired the cups’ austere design. The Admiralty Islands saw the emergence of a penchant for polychrome art unique to the New Guinea area. Some figures are reminiscent of the flat primary style but adorned with black, red, and white triangles.

Transitional Zone Style

The area between Polynesia and Melanesia, which is populated by people from both areas (such as Micronesia, which has recently received Malays), is devoid of any aesthetically significant art. Its wooden statues simplify the human form to its core components. The two-dimensional face is similar to Polynesian Tonga, Melanesian, and Samoan designs. For enjoyment, these primitive artists sometimes disregard pure creativity and replicate what they actually observe in the real world. Figures of a similar sort, most likely contemporary, may be seen in the Fiji Islands, where the Oceanic cultures and blood of two populations mix.

Polynesian Style

The stone figures of Moorea, Tahiti, and Raiatea are rarely more than three feet tall, with the majority being less than half that. There are also little wooden Polynesian artifacts that are perhaps ceremonial artifacts or boat adornments. These figures symbolize the deceased, although the higher gods were also depicted in Polynesian religion. These are rather simple symbols in Tahiti.

Oro, the god of battle, is a sliver of wood the size of a child’s arm coated with a delicate coconut-fiber string network.

The red-tailed tropical bird’s red feathers are connected to it. In the Hawaiian Islands, it is thought that a style of large wooden statue emerged about the 12th century under the influence of Tahiti, with which the Hawaiians had established contacts. On Necker Island, other ancient sculptures have left rough stone remnants, their faces resembling the basic substratum of Oceanic plastic art. The large Hawaiian statues represent the gods who protect the sacred sites and the first white visitors drew pictures of them.

Easter Island

The Moai sculptures on Easter Island are, of course, the most well-known examples of Polynesian art and sculpting. These megalithic monuments include enormous stone heads on tiny bodies, representing the deified dead. Much of the Polynesian people’s art is supernaturally motivated, and the islanders traditionally thought that specific artworks were possessed by spirits with control over global events. When Christianity arrived on the islands, sculpture suffered significantly as the previous ideas about its magical power were no longer accepted.

They did, though, continue to produce on a smaller scale in secular art forms such as textiles such as kava bowl carving. The wood itself is unusual and originates from a single species: the stunted scraggy trunks of the Sophora Toromiro. The water will occasionally toss up a floating tree. As a result, riches in local tales are usually made up of wooden artifacts. Wooden statuettes, as opposed to colossal sculptures, portrayed the deceased or spirits. On feast days, they were in high demand for display around the shrines.

Oceanic Art Key Characteristics

The Lapita were noted for employing a comb-like instrument to stamp clay repeatedly to produce anthropomorphic and geometric motifs on ceramic art. These Oceanic peoples did not consider their creations to be art but rather devoted a lot of time and attention to ritualistic and ceremonial objects. Face painting, in addition to tattooing, is quite popular, particularly among Melanesians. Scholars say that the enormous heads of Polynesian artworks suggest that they believed the head was where the personality resided. The Sulka people of New Britain have a reproductive ceremony that combines mystical, visual, and performance art.

Huge bone marrow and bamboo masks are thought to contain spirits that come to life on specific days, and they are carried around inactive orchards by nude individuals painted red who dance to the rhythmic ritual movement that releases the fertility of the land.

Tattooing is also done by the Maori of New Zealand, who have a particular fixation with curvilinear spiraling. Similar complicated curvilinear designs are used on doors, boats, and any other carved surface. The colossal stone statues of Easter Island were sculpted in less than four weeks and hauled from the quarry by hundreds of men and women.

Around 500 were carved, and many of them are still in the quarry, never having reached their designated altars. The most significant unifying aspect of Oceanic art is its two-dimensional aspect, which is primarily enforced by a poorly developed technique and a few cultural influences. This main style of two-dimensionalism is frequently seen in the face, but also in the entire form, and occurs all the way along the migration path taken by Oceanians from southern Asia. It provides striking evidence of Oceania’s underlying unity of the arts.

Clay was also used in New Guinea and Melanesia, mostly for sculptures, tiny musical instruments, and ceramics. Except in a few small places in New Guinea and the northern Solomons, the creation of clay containers was largely the job of women. The traditional process used spiral coiling clay rollers and men decorated the pot. Simple abrading and drilling equipment were used to work on sea shells and turtle shells. Stone carving, while obviously more difficult and time-consuming than wood carving, was accomplished fairly often and happened across the Pacific Islands; hammering, pecking, and polishing were the primary methods. Even the most resistant substance, jade, was conquered by abrasive grinding.

In Oceanic art, the search for potential artistic material by Oceanic artists was entirely opportunistic; they saw practically anything from the lush natural world around them as potentially useful. Shells of many types were found in the sea, particularly cowrie, conus, and nassa shells. Birds offered beaks, down, and plumes; mammals provided tusks, teeth, and skins; and insects provided their beautiful wing casings. Leaves, flowers, and fibers were sourced from the vegetative kingdom. The combination of such elements into single items was uncommon in Micronesia and Polynesia, but it was common in Melanesian and Australian styles and contributed greatly to their more spectacular results. The human body was the most fundamental medium of all, receiving both permanent and removable embellishments, including scarification in New Guinea, improved by treatment to produce keloid welts, and tattooing with needles and colors elsewhere.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Oceanic Art?

Native Oceanic visual art and architecture include mediums such as ceramics, sculpture, basketry, rock art, masks, painting, and personal ornamentation. Architecture and art have often been intimately linked in these cultures – for instance, storehouses and meetinghouses are frequently ornamented with beautiful carvings, and thus they are discussed together. Oceanian societies used Neolithic technology until the 16th and 17th centuries when European cultures arrived on the scene.

What Are the Characteristics of Oceanic Art Tools?

The fundamental tool throughout the rest of Melanesia, as well as Micronesia and Polynesia, was the stone blade. Tridacna shell was occasionally used for blades in places of Oceania where stone was scarce, such as Micronesia and the Solomon Islands. When obsidian became accessible, it was chipped into blades that could be used as tools and weapons.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Oceanic Art – An Introduction to Traditional Polynesian Art.” Art in Context. August 29, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/oceanic-art/

Meyer, I. (2023, 29 August). Oceanic Art – An Introduction to Traditional Polynesian Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/oceanic-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Oceanic Art – An Introduction to Traditional Polynesian Art.” Art in Context, August 29, 2023. https://artincontext.org/oceanic-art/.