Celtic Art – Stylistic Development of Celtic Cultural Artifacts

Although most people would associate ancient Celts’ art with images of Irish mythology, the truth is that the Celts originated from Ancient Central Europe and not Ireland itself. Celtic sculpture and Celtic paintings – in fact, Celtic art history in its entirety – is a broad term referring to several movements that can be attributed to various people who share a common heritage, yet differ in location and period. It is associated with Celtic-speaking people from prehistory up to the modern era, as well as ancient groups with stylistic similarities to those of the Celts, but whose original spoken language remains uncertain.

What Is Celtic Artwork?

The most prominent perception of Celtic styles usually depicts Irish Celtic art or Gaelic art, but Celtic art history stems further back than this popular misconception in both time and location. What most of the English-speaking world imagines when they think of the term “Celtic Artwork” actually stems from the artwork of the early Middle Ages of Britain and Ireland, which is known as “Insular Art”.

There has been much discussion about the earlier influence from the Bronze Age amongst artistic scholars, but most archeologists prefer to use the term “Celtic” when talking about the cultures deriving from the European Iron age, from approximately 1000 BC onwards. Art historians generally only start referring to “Celtic Art” somewhere between the 5th and 1st centuries BC, known as the La Tène period.

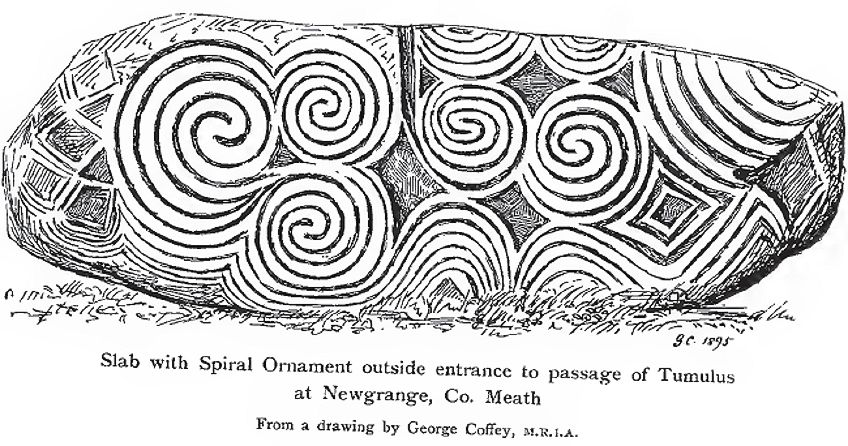

Typically, the overarching themes of Celtic painting and Celtic sculptures are complex symbolism, ornamental geometric designs, and non-linear patterns.

The huge influences derived from interactions with countless previous cultures have resulted in the incorporation of stylistic elements from spirals to key patterns, knotwork, and zoomorphism. The common thread to be found throughout the expansive timeframe and geographical span is the development of a sense of balance in the layout of these patterns. Through the application of curvilinear forms, the use of both positive and negative space result in a harmonious whole.

History of Celtic Styles and Influences

The History of Celtic styles and influences can be separated into various eras. The Hallstatt era is considered to be at the root of Celtic Culture, the La Tène era is considered the prime period of Celtic artwork, and the Celtic Revival represents the more modern interpretation of Celtic art history.

Hallstatt Culture

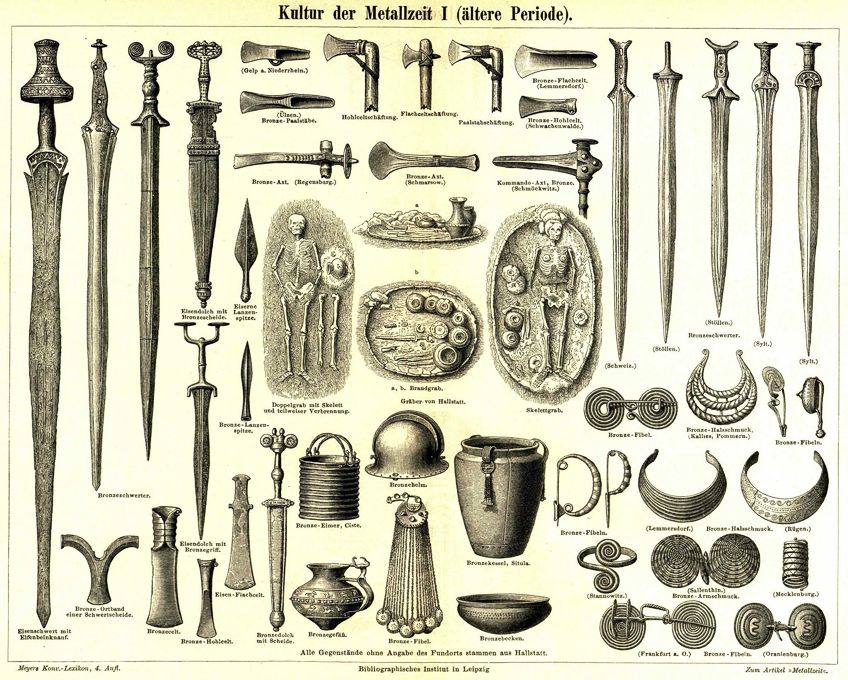

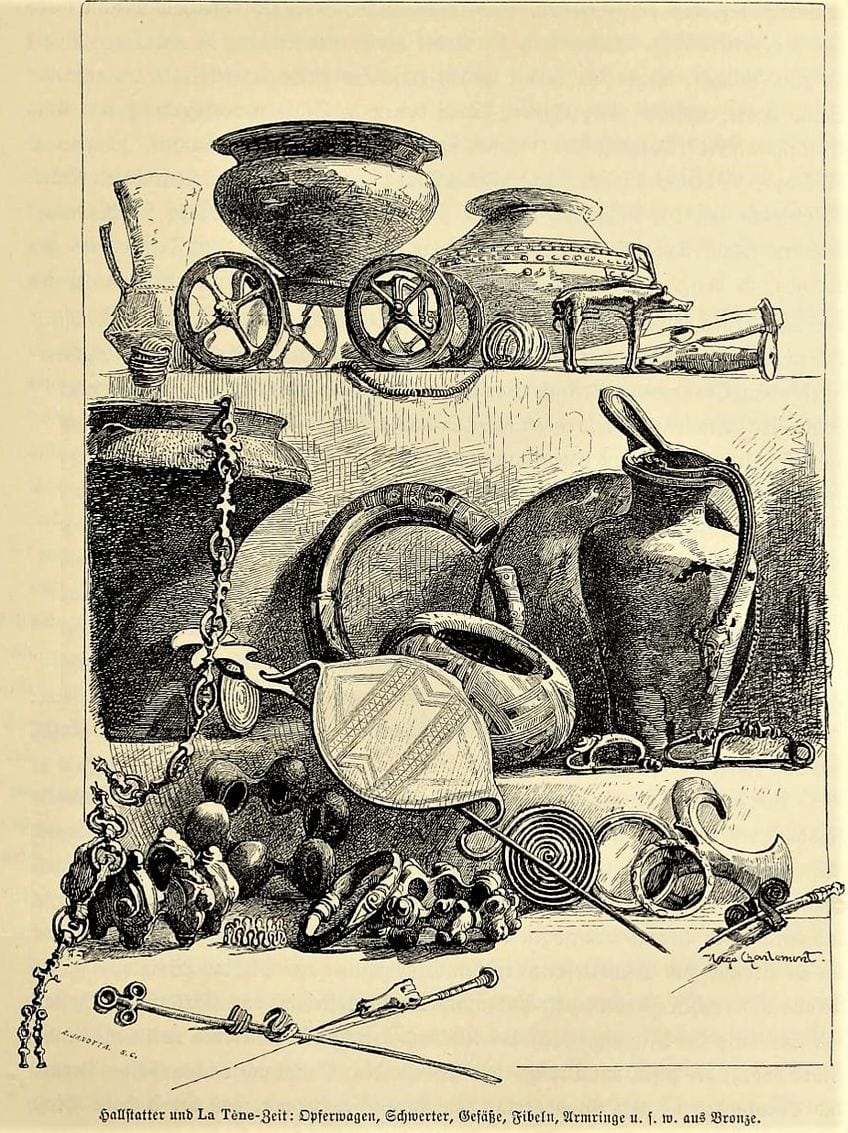

Originating in Austria from roughly 800 to 475 BCE, Celtic art has its roots in the Hallstatt culture. Although it might have its origins in Austria, this culture eventually spread throughout central Europe, encompassing Slovakia, Western Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Southern Germany, Switzerland, Northern Italy, and Eastern France. The Hallstatt culture is quite well known for its ornaments made of bronze, as well as weaponry and iron tools of very high quality.

Common motifs on the weaponry at the time were spirals, geometric designs, and animals. There seemed to be a preference for birds, knotwork, and fretwork.

It was from this period that the Celts developed their own unique culture and styles, derived not only from the Caucasian Bronze Age but also from their interactions with maritime traders through the Black Sea and Mediterranean basin, incorporating styles and techniques from the Etruscan as well as Mediterranean cultures. They eventually settled in the Upper Danube, absorbing the local ancient Danubian motifs along the way.

La Tène Culture

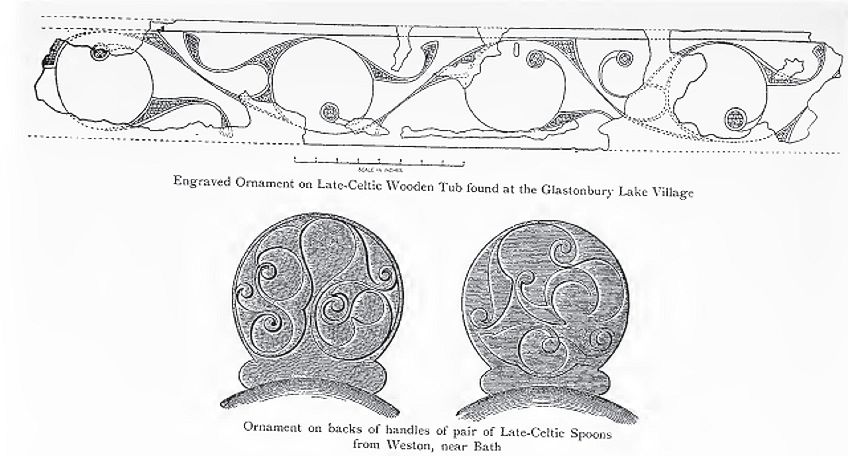

The La Tène period (broadly 5th to 1st centuries BC) is what can be considered the beginning of Celtic art, as far as historians are concerned. It is most easily recognized by its swirling curvilinear patterns. The movement has its origins in Switzerland and is named after the site near the village of La Tène, where Swiss archaeologists and geologists excavated artwork from its discovery in 1857 up until 1885.

Over 2500 objects were excavated at the site, most of which were made of metal and most of them military weapons, typical of the war-like environment of the era.

It is fortunate for archeologists that the era of cremation came to an end around this period, making way for burials. This in turn has resulted in more burial sites and subsequently, more personal and household objects being stashed away with the dead, allowing for excavators to discover them in years to come. Without these invaluable treasures of buried artifacts, we would know very little of the Celtic civilization that we are fortunate enough to know today.

As well as metal, this era was known for artists that worked with gold, specifically for personal adornment such as jewelry. Most of the pieces that still exist today were made from iron, bronze, gold, and other metals. Ivies and foliage were common motifs within the scrollwork to be found on objects such as weapons, sculptures, and vessels like bowls.

This period was considered the “mature” Celtic period and, according to Paul Jacobsthal in his book “Early Celtic Work”, the La Tène movement can be classified as having four distinct stages: the Early style, the Waldalgesheim style, the Plastic style, and the Sword style.

The Early Style (c. 480-350 BCE)

This style is based on the historical excavations at various burial sites in Germany and France, most notably typified by gold collars and other ornate jewelry from Rodenbach and Reinheim. Subsequent unearthings included bronze containers from Kleinaspergle and Basse-Yutz, a large portion of which can be found to be decorated in the idiomatic La Tène-style curvilinear patterns. These patterns included the motifs of lotus flowers, acanthus leaves, and palmettes.

The Waldalgesheim Style (c. 350-290 BCE)

This sub-style derives from pieces of chariot and ornate jewelry found at the Waldalgesheim burial site in Bonn, Germany. It displays a unique combination of Celtic and Classical styles, reflected by growing confidence in the Celtic tradition.

The Plastic Style (290-190 BCE)

This style began to see an increase in the use of images containing animals and humans. It was also highly elaborate, more detailed, and decorative. The Plastic Style period displays a deeper concern for and awareness of three-dimensional effects in ornamental design work.

The Sword Style (190 BCE onwards)

This last style signifies a move away from the detailed and vibrant three-dimensional style figuration of the former Plastic period towards more linear abstraction, which is distinguished by geometric patterns derived from Hellenic floral motifs.

This period focuses on the eastern archeological discoveries of engraved ornamental weaponry.

Owing greatly to the exposure to the Graeco-Roman world, it has been suggested that the artifacts of the Celtic Habituation of the Mediterranean areas have resulted in a greater exhibition of the maturity of expression than their Central European counterparts.

Celtic Art in the Early Middle Ages

From roughly 200 BCE to 100 CE, during the last days of the La Tène period, all Celtic tribes were absorbed into the Roman administration by Roman Legions. Britain too was met with the same fate, although Ireland alone had managed to avoid Roman domination of the area.

It was during the following three centuries that Celtic culture declined almost everywhere except in Ireland. Celtic art stagnated due to the lack of opportunities to practice the skills involved, and it wasn’t until the 5th century that it started to experience a revival.

After the Fall of Rome

Once the barbarian tribes that had resisted Roman occupation eventually succeeded, it led to the fall of the Roman empire in that region. As a result, Christianity began to flourish in Ireland, which directly led to a renaissance in Irish Celtic Art. This rebirth took on three distinct forms:

- A regeneration of Celtic metalwork,

- The production of gospel manuscripts, and

- The creation of free-standing Celtic Sculptures, such as the High Crosses of England.

As can be deduced from the above, the most noticeable shift from the earlier pagan-influenced past of the Celtic tradition is that weaponry and pageantry were the prominent objects created. This new era saw a noticeable shift towards symbolism connected to religious worship and ornamentation. However, this did not deter artists who created Celtic sculpture and Celtic painting from using the spirals, zoomorphic figures, and knotwork associated with their pagan past.

The Picts (Scotland)

The Celtic influence was also to be found in Scotland, as on the west coast, there were shared territories of Irish cultural influences as well as the Anglo Saxon southern kingdom of Northumbria. It was during this period of Christianization that Pictish Art in Scotland began to be heavily influenced by the Insular style, most notably with interlace becoming a prominent feature in stones and metalwork.

Celtic Revival and Global Influence

Celtic Revival art was a style based on an archaic interest in ancient Celts’ art in Britain and Ireland. Mainly decorative stylistically, it first started to emerge in the 1840s and reached its apex in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During this invigorating revival period, the style exerted its influence on textiles and embroidery, metalwork, jewelry, wall decoration, wood inlay, and stone carving. This period saw many masters become highly respected on a global level. Two of these influential artists were Archibald Knox, who was a metalwork designer, and Scotsman Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who was a watercolor artist.

In the 1840s, there was a revival in the interest of Celtic brooch reproduction, which began initially in Dublin, but eventually spread to Edinburgh, London, and abroad.

This interest was largely due to the discovery of the Tara Brooch, which was displayed over the following decades in fashionable hot spots such as Paris and London. The most enduring aspect of the revival in this period was due to the 19th-century reintroduction of using Celtic crosses for monuments at memorials such as graves. This style has not been limited to only areas of Celtic cultural heritage but also spread outwards to neighboring populations.

In the 1900s, it became popular to use interlace as a style of decoration for architectural structures and finishings, especially in America. In Ireland itself, the arts and crafts movement had embraced the Celtic style early on, but by the 1920s, popularity seemed to be on the decline. Today, interlace remains a popular form of decoration in Celtic countries such as Ireland, where it has been adopted as their own. In fact, interlace has become an almost nationally accepted part of the Irish tradition despite having its roots firmly planted in Germanic culture, with equal representation in other cultures such as the Scandinavian medieval arts.

Celtic revivals are periodic, with another Celtic revival surfacing once again in the 1980s, which has endured until this day. The 1990s saw a rise in the number of jewelers and craftsmen incorporating and celebrating the modern revival of a beautiful and ancient tradition.

Notable Celtic Art

Throughout Celtic art history, there have been numerous examples of Celtic sculptures and Celtic paintings that exemplify the most noticeable traits of ancient celts art. Let’s take a deeper look at a few well-known examples of Gaelic art and Celtic styles.

Book of Kells (9th Century)

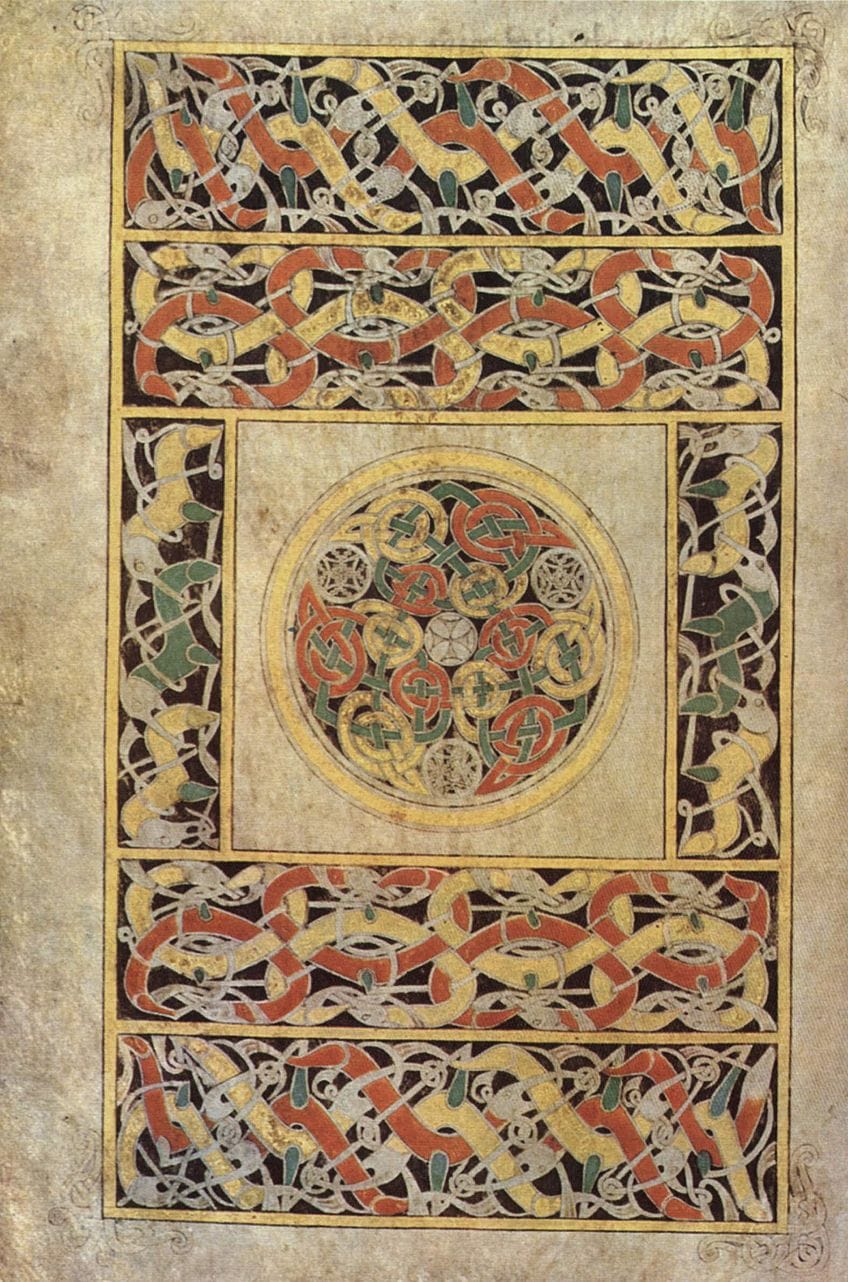

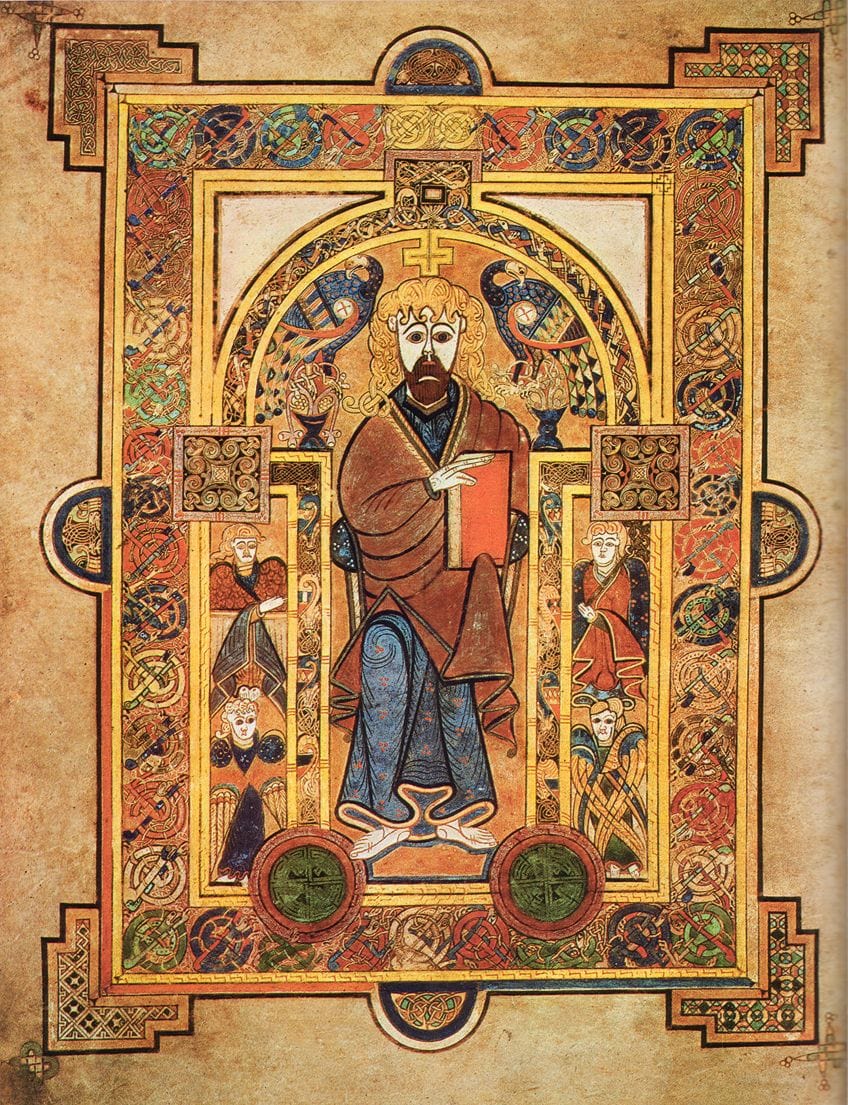

The Book of Kells was written in Latin text in a Columban monastery, approximately around the time of 800 AD. It is a Gospel manuscript from the medieval period and it contains four Gospels found in the New Testament, as well as a collection of various other tables, illustrations, and texts.

For centuries, the Book of Kells found its home in Ireland at the Abbey of Kells in County Meath. Of course, this is also how the book was named. Historians believe the book possibly ended up in Ireland after being raided by Vikings from its original place of creation in Iona, Scotland. The manuscript is particularly noted for its highly detailed ornamentation and illustrations. Stylistically, the book is a combination of Christian and Insular art.

It displays all the hallmark characteristics associated with Celt and Christian styles such as Celtic knots interlaced with geometric designs, curvilinear patterns alongside mythical beasts, and stylized human figures.

Despite enduring years of use, transportation from one place to another, and the constant friction and rubbing from frequent use, the book remains in surprisingly good condition for its age. It is, however, incomplete, with around thirty folios lost to time. If you would like to see the Book of Kells, it is viewable in Dublin where it is displayed at Trinity College.

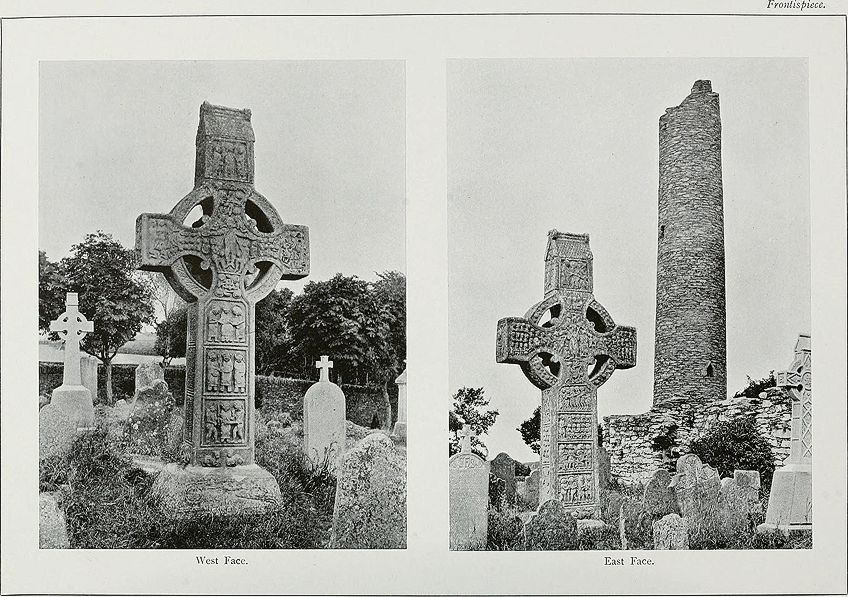

Muiredach’s High Cross (9th – 10th century AD)

Muiredach’s High Cross is a sandstone Christian crucifix, one of three standing crosses situated at Monasterboice, the remains of a secluded religious site in County Louth, Ireland. Collectively, they have been considered the best contribution to European sculpture to come from Ireland.

Muiredach’s High Cross is adorned with carvings of biblical figures and themes.

It is divided into panels, with each panel depicting various religious stories and figures associated with Christian mythology. Archeologists have identified 124 different figures, although not all the panels are biblical, but instead feature geometric shapes and interlaced patterns.

It has been suggested by concerned groups that it would be better to move the cross indoors to protect it from deteriorating further under the harsh conditions of the outdoors. Luckily up until now, the carvings have remained relatively well preserved, with many of the features such as weaponry and clothing of the figures still clearly recognizable today.

Staffordshire Moorlands Pan (2nd century AD)

The Staffordshire Moorlands pan was found in 2003 in Ilam parish, Staffordshire, by metal-detectorists, and two years later, in 2005, it was purchased collectively by the Tullie House Museum in Carlisle, the Potteries Museum in Stoke-on-Trent, and London’s British Museum. This pan originally had a flat handle, but today it has none, nor does it have a base. It is made of copper-alloy and has been enameled.

Bearing inscriptions referring to Hadrian’s Wall, it is believed to have originated sometime in the 2nd century AD.

Many people in the region consider it to contain much significance, not only locally but for many abroad too. Using blue, yellow, and red curvilinear ornamentation, the pan is decorated in a Celtic style. It also has a beaded rim and polychrome enamel inlay. The Staffordshire Moorlands pan is round and features a raised foot-ring. Based on observations regarding the inscriptions decorated around the pan, it has been suggested that the pan served a decorative yet functional role, most likely for someone stationed at Hadrian’s Wall.

The Tara Brooch (c. 710-750 AD)

The Tara Brooch is a pseudo-penannular Celtic brooch, estimated to have been made somewhere between 710 to 750 AD. According to the National Museum of Ireland, the Tara Brooch in many aspects represents the apex of what could be achieved by the craftsmen of the time.

It was found in 1850 near Bettystown, on the coast of County Meath and not at Tara, as some had thought. The brooch was named after the jeweler who eventually purchased it, mostly as a manner of branding the copies of the brooch that were later manufactured.

The brooch was exhibited internationally in places such as London and Paris, which helped fuel its legacy as one of the artifacts responsible for the mid-19th century Celtic revival. Its current location is the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin, where it is displayed for the public to view.

The Battersea Shield (c. 350-50 BC)

The Battersea Shield was dredged up from the bed of the River Thames in 1857. Since then, many groups have tried to date the piece, considered to be one of the most significant pieces of ancient Celtic art found in Britain. The shield is currently housed at the British Museum, having been dated to circa 350 to 50 BC. However, dates as late as the early first century AD have also been suggested, and most tend to favor the later date range as the most likely potential time frame.

During the same excavation, workers brought large quantities of Roman and Celtic weapons from the muddy depths of the riverbed. This led many to speculate that this was the possible site of Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain in 54 BC, although most agree that the shield predates the invasion and was most likely a votive offering.

The Desborough Mirror (c. 50 BC-50 AD)

This bronze mirror has been considered one of the finest examples of La Tène or Celtic art from Britain. To produce a reflective surface, the plate was highly polished on one side, and the backplate was engraved with a complex design. In a period where one’s reflection could normally only be observed in water, this would have been considered both a wonder and a novelty. Highly decorated mirrors of this type are uniquely British, and very few are found on the continent of Europe and elsewhere. The majority that of decorative mirrors that been uncovered are from graves dating between 100 BC and 100 AD.

Notable Celtic Revival Artists

Celtic art history has left us a treasure chest of artworks made by Celtic painters that date back centuries. There have been several revivals up to the modern age, both in Ireland and abroad. Not only has there been a resurgence in Irish Celtic art in the UK itself, but Celtic styles have influenced artists even in countries like America.

John Duncan (1866 – 1945)

Originally hailing from Scotland, the painter John Duncan was a noteworthy Celtic Revival artist who worked with an assortment of mediums, including stained glass. He was born in Hilltown, Dundee on 19 July 1866, as the son of a cattleman and butcher. However, John had a passion for the visual arts and had no desire to follow in the footsteps of his parents and join the family business.

At the young age of fifteen, he was already submitting cartoons to “The Wizard of the North” (a local magazine) and later worked his way to assistant in the art department of the Dundee Advertiser. He studied at the Dundee School of Art and by 1888, was working as a commercial illustrator in London. He then moved to Europe to study at Antwerp Academy under Charles Verlat as well as at the Düsseldorf Art Academy.

Duncan is most well-remembered for his pieces The Glaive of Light (1897), Hymn to the Rose (1907), Riders of the Sidhe (1911), and Tristan and Isolde (1912), and has created multiple Celtic and symbolist artworks that have been exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy and the Royal Glasgow Institute.

Thomas Augustin “Gus” O’Shaughnessy (1870 – 1956)

Thomas Augustin O’Shaughnessy was an American Irish Celtic Art Revival designer, known for creating stained glass designs inspired by Celtic art. Much of his work helped him gain respect all over the globe thanks to his excellent Celtic Revival designs.

Before going back to Europe where he would perfect his art and continue learning new techniques, Thomas was at the Art Institute of Chicago. This is where he studied under the guidance of Louis Millet, who is a master stained-glass artist. He was also a member of the Chisel Academy of Fine Art, as well as the group known as the Chicago’s Palette. Thomas Augustin O’Shaughnessy also made stenciling for the interior of the Old Saint Patrick’s Church in Chicago and helped in designing and installing the church’s stained glass windows between the years 1912 and 1922.

Thomas Augustin O’Shaughnessy drew huge inspiration directly from the Book of Kells, and after having recently been restored to his vision in 1996, his artwork continues to challenge conventional notions of Irish identity and sacred space even from the far-flung shores of America. Two classic examples of his stained glass work can both be found at Old Saint Patrick’s Church in Chicago, being O’Shaughnessy’s depiction of ‘St. Brigid’ as well as the “Great Faith Window”.

We have now learned that Celtic art history has roots deep in ancient European culture and not just in Ireland, as one might have originally thought. We have covered the early influences, the prime era, the fall, and the revival of this style in modern times. It was through these revivals that craftsmen continued to be inspired by ancient art, even up until this very day.

Take a look at our Celtic artwork webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

In Which Period Did Celtic Art Originate?

Although influences can be traced back as far as the Bronze Age, most art scholars agree that the period of the La Tène culture is the original era in which the style developed what is considered the Celtic idiom. La Tène culture originated in the mid-5th century BC. Although this is considered the true starting period of the traditional Celtic style, it had been heavily influenced by Hallstatt culture.

Does Celtic Art Still Exist?

There have been several revivals of Celtic artwork throughout human history, and Celtic art continues to influence artists and craftsmen up until today. Celtic art has had an influence on artists across the globe during several periods of revival. This includes places such as America where artists such as Thomas Augustin “Gus” O’Shaughnessy gained huge popularity as revivalists of the style.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Celtic Art – Stylistic Development of Celtic Cultural Artifacts.” Art in Context. August 13, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/celtic-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 13 August). Celtic Art – Stylistic Development of Celtic Cultural Artifacts. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/celtic-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Celtic Art – Stylistic Development of Celtic Cultural Artifacts.” Art in Context, August 13, 2021. https://artincontext.org/celtic-art/.