Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley – An Analysis

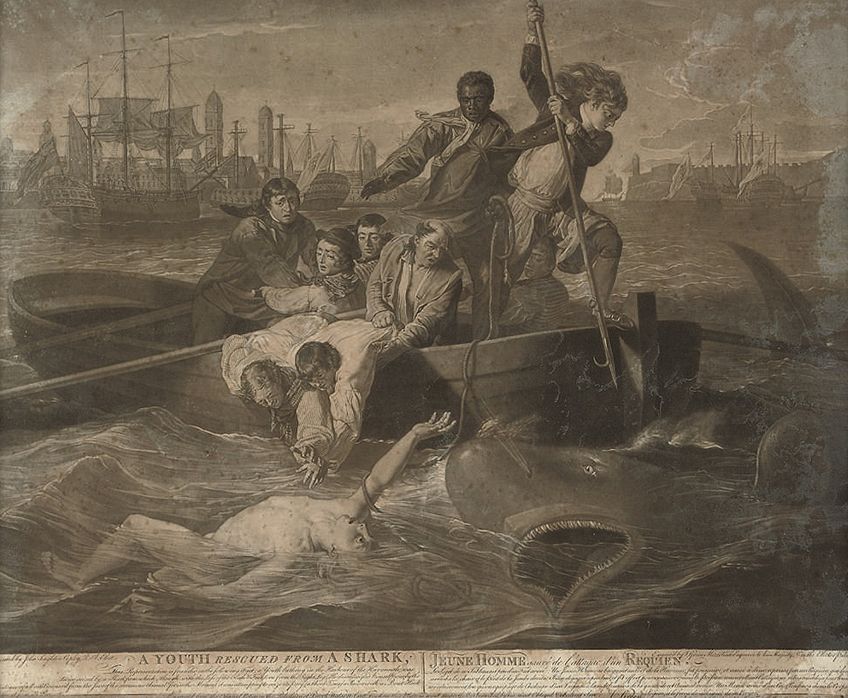

It was the year 1749, and Brook Watson decided to go for a swim in the sea at Havana Harbor in Cuba. Whilst swimming, a shark attacked him twice – a crew of nine men rescued him just before the shark could get a hold of him for the third attempt. This traumatic and heroic scene has been immortalized as the famous Watson and the Shark painting, created by John Singleton Copley in 1778.

Artist Abstract: Who Was John Singleton Copley?

John Singleton Copley was an Anglo-American artist, reported to have been born in Boston, Massachusetts. He was considered to be one of the most influential colonial painters of his time, popular for his portrait paintings and historical paintings. He first lived and worked in America as an artist and in 1774 moved to London, England, where he further developed his career, notably his historical paintings. He created over 300 artworks and was a pioneer of the American realist painting genre.

Watson and the Shark in Context

| Artist | John Singleton Copley |

| Date Painted | 1778 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Genre | History Painting, Animal Painting, and Marine Art |

| Period | Romanticism |

| Dimensions | 182.1 x 229.7 centimeters |

| Series / Versions | First of three versions |

| Where is it housed? | The National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.) |

| What It Is Worth | Price Unknown |

In this article, we will discuss what is considered to be the most well-known of John Singleton Copley’s famous paintings of the 18th Century, Watson and the Shark (1778). First, we will look at some of the socio-historical aspects that have shaped the subject matter of this painting, exploring questions of why it was done and its inherent symbolism. Secondly, we will look at the visual compositional aspects that shape the painting. There is a lot happening in this historical artwork, so let us have a look and see what we can find.

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

We have already introduced Brook Watson, the main protagonist of this painting, but what we do not know about him is that he was 14 years old when the shark attack occurred. In 1741, Watson was orphaned (it is assumed his parents died) and he was sent to live with his distant relatives in Boston (some sources suggest they were his aunt and uncle). His uncle was a merchant and traded in the West Indies.

Brook started working as a crew member on one of the ships in the area. While they were docked in Havana Harbor in Cuba, Watson went for a swim in the nude.

In the first instance when the shark attacked him, it stripped off the skin from his right ankle; in the second attack, the shark bit off his ankle. Before the shark could reach him for the third attack, a boat and nine men managed to save Watson and drive a boathook into the shark. The resulting attack cost Watson his right leg, which was amputated below the knee.

Watson led a full life and became a merchant himself and served in the military. He was also a member of Parliament from 1784 to 1793 and the Lord Mayor of London in 1796, including being the director for the Bank of England, among others. He became well known and illustrated with his peg leg in numerous images. He was also slandered by political opposition in a poem written about his leg:

“Oh! Had the monster, who for breakfast ate

That luckless limb, his noblest noddle met,

The best of workmen, nor the best of wood,

Had scarce supply’d him with a head so good”.

Regardless of how Watson was perceived or illustrated, he became a famous historical figure. It was not only because of his amputation but also because of his successful career as a man of many trades. The Watson and the Shark painting gave him an extra boost as a heroic survivor of nature’s seeming rawness.

In fact, it was Watson who commissioned the artist John Singleton Copley to paint the ordeal from his teen years; the two gentlemen met in London in 1774 and became friends. After Copley finished the painting in 1778, it was exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. It was first (quite lengthily) titled as, A boy attacked by a shark, and rescued by some seamen in a boat, founded on a fact which happened in the harbour of the Havannah.

The painting received positive acclaim by various British newspapers after it was exhibited and many reviews lauded the narrative. For example, The General Advertiser, and Morning Intelligencer newspaper for 27 April 1778 stated, “Its whole is very fine, though there are some inaccuracies in its parts. The story is well told”.

Regarding the painting’s “inaccuracies”, many critics also pointed out the unrealistic aspects of the scene. For example, the shark did not really resemble a shark, the men on the boat could not have realistically saved Watson as they held the rope in an “un-sailor-like” manner, and the water was too calm for what was occurring.

The History Painting Genre

It is worth noting that Copley was a leading artist of the History painting genre, alongside fellow artist Benjamin West, and their paintings were often compared in similarities. West was popular for depicting historical narratives with a modern twist, for example, The Death of General Wolfe (1770), which had been painted almost 10 years earlier.

West’s painting was a historical recount of the Battle of Quebec in 1759.

It portrayed the scene at the intense moment when General Wolfe was dying. This painting went against the conventions of historical paintings, as West portrayed General Wolfe, surrounded by various figures, all clad in modern outfits instead of the characteristic classical robes (or togas). He also portrayed a modern event and not a Biblical or mythological scene.

Another important fact about Copley’s Watson and the Shark painting is the artist portrayed someone (Watson) entirely obscure and unknown in the public eye of society. No one knew who the characters portrayed in the scene were either.

This reminds us of what historian Louis P. Masur described in his article, Reading Watson and the Shark, published in The New England Quarterly Vol. 67, No. 3 (September 1994). He stated that “history is democratized and the anonymous seamen are shown to be as deserving as any general of the temporal and spiritual rewards of virtuous, selfless action”.

Masur also described West’s approach to his painting of General Wolfe, stating that “heroism did not have to be tied to ancient models to inspire or instruct the viewer”. And furthermore, explaining Copley’s approach to his shark painting, Masur wrote, “Watson and the Shark would blur the boundaries of history painting even more, as it drew an obscure event from the recent past and elevated it to historical importance by treating it in a full-size oil painting”.

Ironically, Copley actually painted three versions of this painting, replicating the same subject manner in much the same way that Renaissance artists would paint multiple versions of religious figures, such as the Madonna with Christ.

By placing the everyday person in the spotlight of hero or martyr, this new approach to the historical genre was wholly different from the traditional Biblical narratives where religious and mythical figures were given the spotlight.

Formal Analysis: A Brief Compositional Overview

There are many facets to the Watson and the Shark painting. Not only is it packed with historical narrative, but it also tells a visual story through its compositional and stylistic rendering. Below, we will explore the subject matter and the way the figures were portrayed, especially Watson, as well as the symbolism behind these.

Subject Matter

When we look at the Watson and the Shark painting, we see in the left foreground the figure of Brook Watson in the water. His nude body floats on the water’s surface; his right arm is outstretched towards the nine men in the boat approaching to rescue him while his left arm is to his side. Two men hang out of the boat to reach towards Watson while another in the boat holds onto them to anchor them.

We notice four men, who appear to be the rowers, gazing in anticipation at the scene. Further to the right of the boat (from the viewer’s point of view), there are two men standing. The first is African, notably the only African on the boat, who is holding the rope thrown out to Watson. The other man is in the action of piercing the shark in the water with a boathook. The shark appears in the right foreground of the composition, closing in on Watson’s figure in the water.

The shark’s body also appears very long as the back fin can be spotted all the way on the other side of the boat, suggesting the creature’s enormity.

The surrounding background depicts various ships and buildings, suggesting the Havana Harbor where this historical event is taking place. The water surrounding the figures is depicted in undulating waves in the foreground, but calmer towards the background.

The entire scene depicts a moment of intense and engaged action: The boatmen are fervently trying to rescue Watson, and the shark is seemingly not hesitating at all to home in on its prey. We are drawn into the scene and left aghast, wondering what will happen next.

For anyone who does not know the story behind the painting, it might even be assumed that the boy did not survive this ordeal.

An interesting fact about this painting is that it inspired the subject matter of many other artists and writers. For example, the Raft of the Medusa (1818 to 1819) by French artist Théodore Géricault and Herman Melville’s classic novel, Moby-Dick (1851).

Artistic References and Religious Symbolism

There are numerous references to classical sculptures and paintings, and Copley’s figures resemble these. Copley was influenced by several famous art pieces during the time he painted Watson and the Shark, and it has been noted that many of these references were from religious narratives.

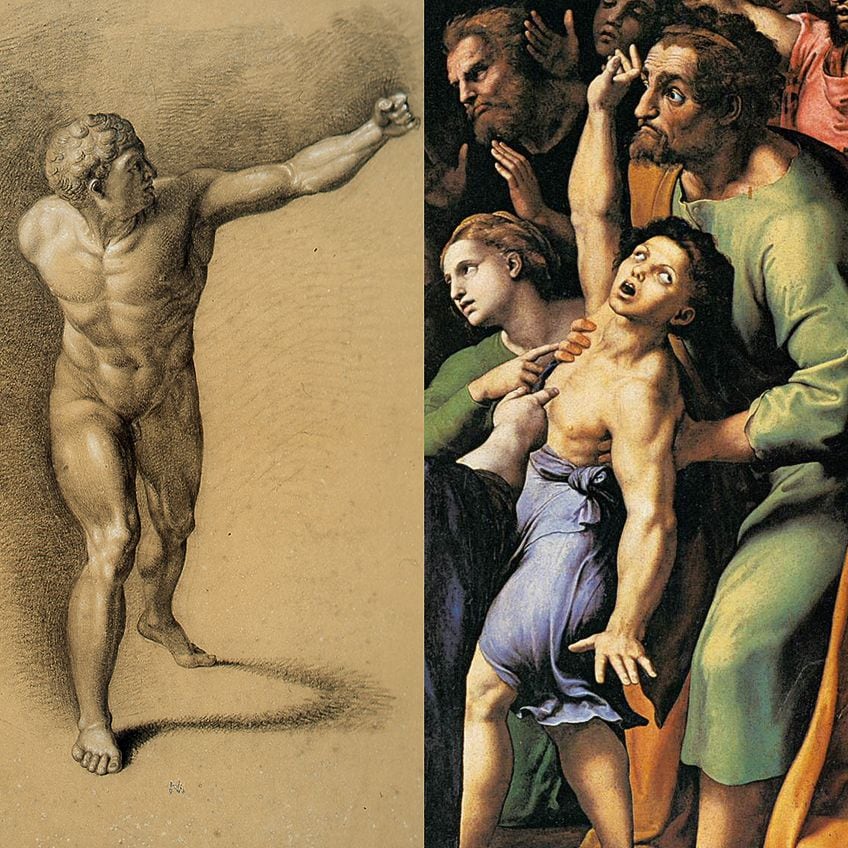

The figure of Watson is indicative of the Borghese Gladiator (c. 100 BCE), believed to have been sculpted by Agasias of Ephesus. It is a life-size marble statue of a warrior with his left arm outstretched. The floating figure of Watson in the water, if standing, is in a similar stance as the warrior mentioned above.

Furthermore, Watson also resembles one of the figures in the painting Transfiguration (1516 to 1520) by Renaissance artist Raphael, possibly the figure to the right of the composition with his right arm outstretched in a similar fashion to Watson. Watson’s head also borrows from one of the son’s heads depicted in the famous Laocöon and his Sons (c. 42 BCE to 20 BCE) sculpture, by three possible sculptors, namely, Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes.

When we look at the other figures in the boat, such as the two men trying to reach for Watson, they resemble the fishermen in Raphael’s drawing, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (1515 to 1516). Additionally, the man with the boathook about to pierce the shark resembles St. George (see St. George and the Dragon by Raphael, 1504-1506) and St. Michael (see St. Michael the Archangel by Guido Reni, 1636).

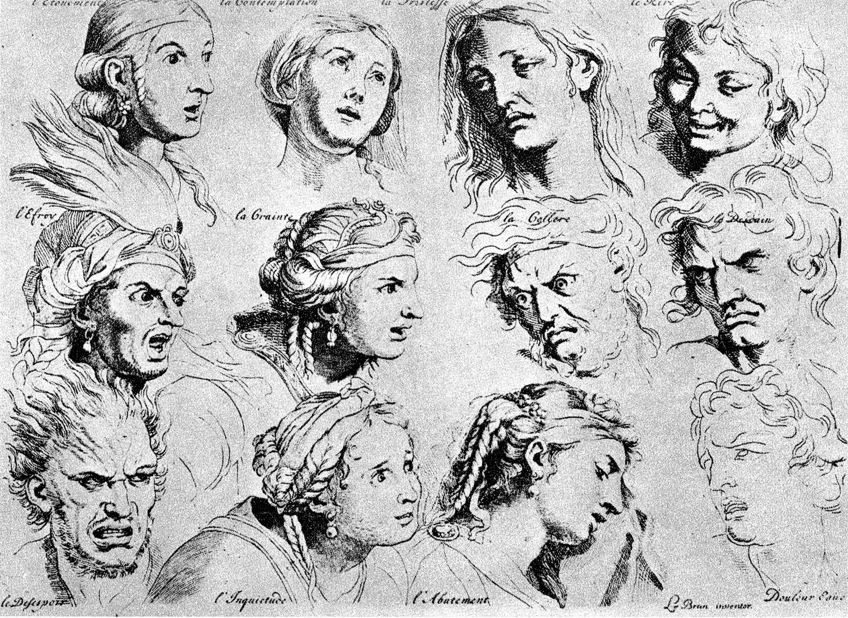

Face Up: The Influence of Charles le Brun

Other than artistic references, another important characteristic of the Watson and the Shark painting is the facial expressions given to each of the men. For this, Copley referred to the influential work of the French artist, Charles le Brun. Le Brun studied facial expressions and published a book on the subject, titled Méthode pour apprendre à dessiner les passions (1698).

Some of the facial expressions and their related emotional states include attention or contempt, such as for the man holding the boathook; the man far left in the boat shows dread; the man with the rope shows compassion, and the older man shows astonishment.

Ultimately, the figures play a significant role in this painting, such as the African figure holding the rope. It is also mentioned that he is the only one holding the rope, which is Watson’s very “lifeline”.

There are different interpretations about this man. For example, he could be regarded as the hero saving Watson because he holds the rope, or perhaps his more passive countenance could be emphasizing the more active stance of the man with the boathook.

This figure resembles the man in Copley’s Head of a Negro (1778), as Copley was believed to have a fondness for him. His inclusion has also been speculated as an antislavery suggestion. The figures are also clad in different outfits. Some appear wealthier, such as the man with the boathook, who is wearing fashionable regalia of the times like buckled leather shoes and a coat. The men also fall into different age groups, from young to old.

Color

Copley paints in subdued colors, the green of the sea extending far into the background met by the blues and whites of the sky and clouds. The overall painting appears almost hazy in its color scheme, perhaps mimicking the foggy air one experiences at sea. We also notice variations of browns from the blurred ships in the background and the boat in the foreground.

There is an interesting play on light and dark in the foreground of the painting.

The shark almost emerges from a more darkened, shaded area in the bottom right corner of the painting. This seems to juxtapose the unknown light source over Watson’s body and the men on the boat. This light source also appears to highlight these central figures and the main action of saving Watson.

Line and Space

The depth and spatial awareness of the painting are created by a strong play on vertical, horizontal, and diagonal lines, emphasizing the action and keeping us enthralled in the dynamic tension. We notice the horizontal lines from Watson’s body in the water, the shark, the boat in the foreground, and the buildings and ships on either side in the background. The horizontal lines interplay with the diagonals created from the waves on the water, the oar to the left, Watson’s arm reaching towards the boat, as well as the men in the boat.

Collectively, a “compositional triangle” is created, further placing emphasis on the central figures and creating a zig-zag effect of lines that move our gaze towards the background.

The vertical aspects of the painting are indicated by the standing figure of the man with the boathook and the boathook itself. We also notice how the harbor in the background opens in the far distance, which is directly behind the man with the boathook – this could also highlight the significance of this figure and that he is the one saving Watson from the shark.

Scale

Copley painted three versions of Watson and the Shark. The original 1778 version discussed here is housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. in the United States and measures 182.1 x 229.7 centimeters. It was also one of Copley’s first large-scale paintings done after primarily painting portraits. The second version, which is a replica, is housed in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the third version was painted in 1782; it is smaller and more vertical and housed in the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Overcoming Adversity: “A Most Useful Lesson to Youth”

The Watson and the Shark painting explores many themes, one common theme being that of resurrection. Although Copley did not paint in the traditionally expected manner of religious or mythological figures, the message and motifs conveyed are those of classical narratives we find from the Bible, namely resurrection, martyrdom, and overcoming adversity.

The nude figure of Watson, highlighted by an unknown light source, suggests to us someone who is being saved. We see the implicated idea of salvation, and the real-life tale of Watson and the shark facilitates the above.

Although this painting is also based on a factual event, Copley created the visual scenery from an artist’s creativity, a couple of engraved prints of Havana Harbor, and no first-hand experience of seeing Cuba or a tiger shark.

After Brook Watson’s death in 1807, the painting was donated to the Christ’s Hospital (a charity school) in Sussex, England. Watson’s wish for the painting was to inspire other children or orphans at the school. Watson explained in his will that (the said painting) should be “hung up in the Hall of their Hospital as holding out a most useful Lesson to Youth”.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Watson and the Shark?

Watson and the Shark (1778) is an oil painting done by the American artist, John Singleton Copley. It is considered to be the most well-known out of John Singleton Copley’s famous paintings of the 18th Century. It depicts a cabin boy called Watson, who went out for a swim at Havana Harbor, but he was attacked by a tiger shark and rescued by crewmates from their docked ship. There are three versions of this famous painting: one is the original from 1778, the second is a replica, and the third is a smaller more vertical size from 1782.

Who Was Watson in the Watson and the Shark Painting?

Watson, his full name Brook Watson, was a 14-year-old boy (orphaned when he was young and sent to live with his aunt and uncle) when the shark attacked him. He was a cabin boy for a ship docked at Havana Harbor. He survived the shark attack and grew up to be a successful businessman, politician, and also served in the military. Some of his accolades include being a member of Parliament from 1784 to 1793, the Lord Mayor of London in 1796, and the director for the Bank of England.

What Does the Watson and the Shark Painting Mean?

Some sources suggest that there are religious themes in the Watson and the Shark painting, due to the artist’s strong religious beliefs as a Christian. Some of the meanings and themes are about “resurrection and salvation”, which are especially evident in how Copley depicts the nude body of Watson in the water, almost as if he is passionately surrendering to a higher power.

What Genre of Painting Is Watson and the Shark?

The Watson and the Shark painting falls under a couple of different genres; however, it is regarded predominantly as a historical painting because it depicts the origins of a true story and the heroism of Brook Watson. This was also a genre pioneered by the artist at the time, who lived in London. It is also considered an animal genre painting because of how Copley portrayed the shark, having placed significant emphasis on the shark as a great, formidable force to be reckoned with, which is a characteristic of the genre of animal painting.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley – An Analysis.” Art in Context. August 24, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/watson-and-the-shark/

Meyer, I. (2021, 24 August). Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley – An Analysis. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/watson-and-the-shark/

Meyer, Isabella. “Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley – An Analysis.” Art in Context, August 24, 2021. https://artincontext.org/watson-and-the-shark/.