Frida Kahlo Paintings – Looking at Frida Kahlo’s Most Famous Paintings

Frida Kahlo is regarded as a folk hero due to her distinct character and diverse background. She has become a symbol of female willpower, a passion for Mexico and its history, and tenacity in the presence of adversities. Beyond all else, she was an authentic female who stood firm in her beliefs. Frida Kahlo’s original paintings typically had deep personal themes and blended reality and imagination. If you have ever asked yourself “what is Frida Kahlo known for?”, then look no further, we will be taking a brief look at her life as well as Frida Kahlo’s most famous paintings.

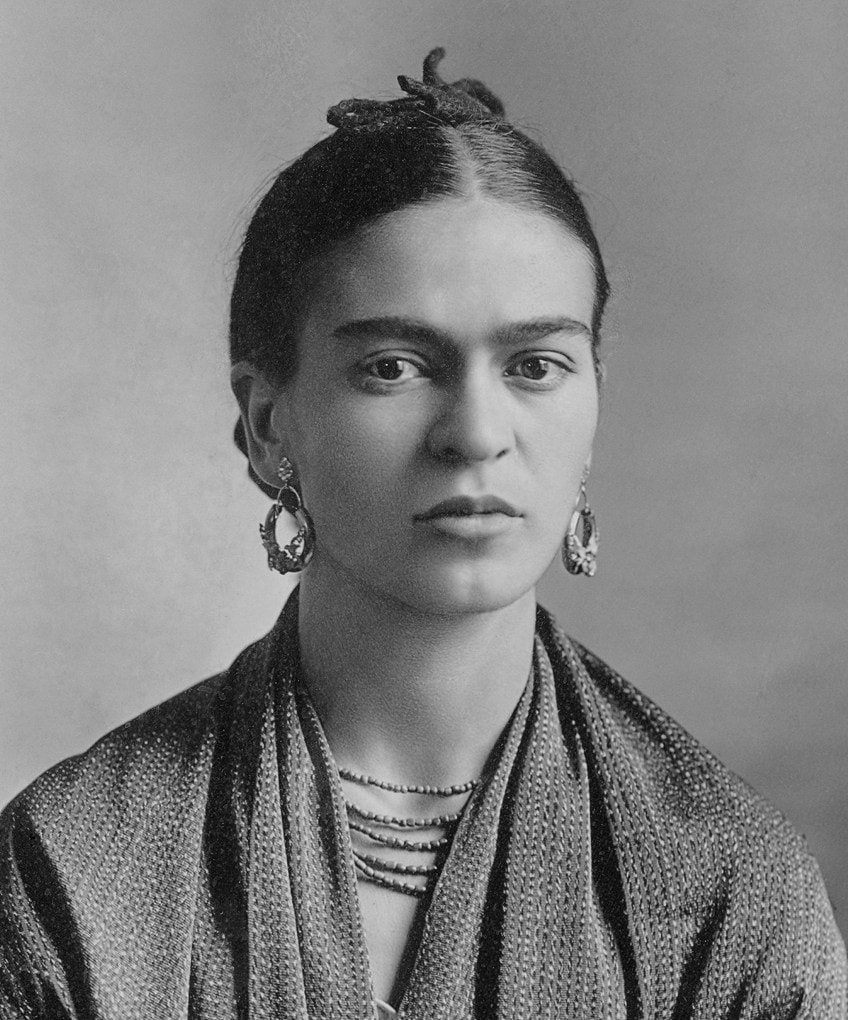

Who Is Frida Kahlo?

Frida Kahlo was a Mexican artist who explored various topics like race, gender, and sexuality in her paintings. She is renowned for her provocative and often autobiographical artworks, and today, Kahlo stands as a respected feminist icon and famed artist.

She was born in 1907 at the Blue House in Coyoacan, a village on the fringes of Mexico City. Her father, Wilhelm, was from Germany and had migrated to Mexico in his youth, where he resided for the remainder of his lifetime, ultimately taking over his family’s photographic company. Matilde, Frida Kahlo’s mother, was of blended Mexican native and Spanish heritage and reared Frida and her younger siblings in a disciplined and devout home.

Kahlo always asserted to have been born in 1910, the very same year as the revolution in Mexico, so that others might link her with contemporary Mexico.

This insight unveils to us a unique persona, marked since early life by a profound feeling of autonomy and defiance against customary moral and social practices, moved by devotion and passion, supportive of her “Mexicanidad” and traditional beliefs set against the ruling Americanization while maintaining a distinctive sense of humor. She was also known for her famous art quotes – you can read through them in our “Frida Kahlo Quotes” article.

Her life was defined by severe pain, beginning with polio at five years of age and later followed by a bus accident that resulted in extensive damage to her body. Many of her masterpieces were created when she was resting in bed. Kahlo’s paintings are typically marked by depictions of agony, owing to her personal traumas, losses, and multiple procedures. 55 of the 143 artworks are Frida Kahlo self-portraits, which frequently include allegorical depictions of physical and mental scars.

As a youthful painter, Kahlo contacted the legendary Mexican artist Diego Rivera, who acknowledged that Frida Kahlo’s art style was really original and distinctively Mexican.

They wed in 1929, against Kahlo’s family’s displeasure, separated, and then married again in 1940. She had several partners, both males and females, including Leon Trotsky and the wife of André Breton. She remarked in her journal just several days prior to her passing on July 13, 1954, “I trust the departure is pleasant – and I wish not to ever come back – Frida.” The official coroner’s report stated that pulmonary embolism was the cause of death, although several speculated that she died of an accidental overdose.

A Look at the Most Important Frida Kahlo Paintings

Now that we have a better understanding of the person, it is now time to dive into Frida Kahlo’s famous paintings. They will give us insight into the importance of Frida Kahlo’s art style and motivations. These paintings by Frida Kahlo will also present even deeper insight into her psyche and thoughts than her biography.

Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931)

| Date Completed | 1931 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 100 cm x 78 cm |

| Currently Housed | San Francisco Museum of Modern Art |

It’s as though Kahlo is trying on the homemaker role in this piece to see how it suits her. She is unconcerned with her status as an artist, preferring to play a submissive and supporting position, grasping the hand of her creative and famous spouse. It is true that for the bulk of her artistic activity, Kahlo was shrouded in the shadow of Rivera, and it would only be later in her lifetime that she achieved widespread acclaim. This early double-portrait was created largely to commemorate Kahlo’s wedding to Rivera.

While Rivera is holding a palette and brush, symbols of his creative prowess, Kahlo restricts her position to that of her spouse by portraying herself in a small frame and without her creative accessories.

Kahlo also appears in the customary Mexican female’s attire, donning a typical crimson cloak called the rebozo and jade jewelry. The posture of the characters is similar to that of customary marital portraits, in which the woman is positioned to the left of her spouse to symbolize her lower social position as a female. The painter does grasp her personal palette in a sketch done the next year called Frida and the Miscarriage as if the trauma of losing a child and not being able to make a family redirects her focus entirely to the production of art.

Henry Ford Hospital (1932)

| Date Completed | 1932 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 30 cm x 38 cm |

| Currently Housed | Dolores Olmedo Collection, Mexico |

A large number of Frida Kahlo’s paintings from the 1930s particularly in scale, format, structural location, and spatial configuration, are related to theological ex-voto artworks, of which she and Rivera owned a significant library spanning many hundreds of years. Ex-votos are deposited in temples or monuments as a show of thanks for redemption, an answered plea, or avoided calamity.

Ex-votos are often created on tiny metallic surfaces, depicting the occurrence as well as the Virgin or saints to whom they are presented.

Kahlo employs the ex-voto method but undercuts it by putting herself in the center position instead of documenting the wondrous actions of martyrs in Henry Ford Hospital. Rather, she depicts her own tale, as if she’s a martyr, and the artwork is created not in gratitude to the Almighty, but in rebellion, wondering why he causes her agony.

In this artwork, Kahlo is hemorrhaging on a mattress after a miscarriage. Six vein-like streamers run forth from the bare nude torso, each linked to a symbol. One of the six items is a fetus, implying that the streamers are an analogy for umbilical cords. The rest of the objects that encircle Kahlo are objects she recalls or has seen while in the clinic. The snail, for instance, refers to the time it took for the miscarriage to end, but the blossom was a real thing presented to her by Diego.

The painter displays her urge to be connected to everything around her, including the everyday and symbolic as well as the tangible and real. Perhaps it is through this trying to connect that Kahlo attempts to be motherly despite her inability to have her own baby.

My Birth (1932)

| Date Completed | 1932 |

| Medium | Oil on Zinc |

| Dimensions | 30 cm x 35 cm |

| Currently Housed | Private Collection |

This is a disturbing artwork where both the giver of birth and the infant born appear to be deceased. The mother giving birth has her head wrapped in white linen, and the infant coming from the belly seems dead. Because Kahlo’s mother had just passed at the moment she created this piece, it appears plausible to infer that the veiled funeral figure is her mother and the infant is Kahlo. She had recently lost her own kid and has stated that she is the unnoticed mother figure. The Virgin of Sorrows, which hangs over the bed, implies that this is a depiction of parental agony and grief.

Next to numerous little sketches of herself, Kahlo wrote in her journal, “the one who birthed herself is also who composed the most exquisite poetry of her life.”

Similar to several other of Frida Kahlo’s original paintings, this artwork depicts Kahlo grieving the death of a child while having the fortitude to create great work as a result of such grief. The artwork is done in a devotional style, a tiny indigenous Mexican picture inspired from Catholic Church iconography) with gratitude to the Virgin underneath the picture.

Rather, Kahlo left this part vacant, as if she is unwilling to express gratitude for either her own conception or the condition that she is now unable to bear children.

The picture appears to convey the notion that it is critical to recognize that conception and mortality are inextricably linked. Many people believe that My Birth was greatly influenced by an Aztec sculpture Kahlo kept at home depicting Tlazolteotl, the Deity of Fertility and Midwifery.

My Grandparents, My parents, and I (1936)

| Date Completed | 1936 |

| Medium | Tempera and Oil on Zinc |

| Dimensions | 31 cm x 34 cm |

| Currently Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York |

This dreamy family tree was produced on zinc instead of canvas, emphasizing the creator’s interest with her appreciation of 18th-century Mexican retablos. Kahlo produced this piece to highlight both her European Jewish ancestry and her Mexican ethnicity. Her father’s side, German Jewish, is portrayed on the right-hand side of the painting by the ocean (reflecting her father’s trip to Mexico), while her mother’s half, Mexican, is presented on the left by a chart softly delineating Mexico’s geography.

While Frida Kahlo’s famous paintings are unmistakably personal, she frequently utilized them to convey subversive or geopolitical ideas.

This picture was made just after Hitler enacted the Nuremberg laws prohibiting mixed marriages. Here, Kahlo concurrently acknowledges her mixed background while confronting Nazi ideology, employing a structure used by the Nazi regime to assess ethnic superiority – the genealogy tree. Aside from geopolitics, the crimson thread used to bind the relatives recalls the umbilical cord that ties infant Kahlo to her mom, a theme that appears within many paintings by Frida Kahlo.

Fulang-Chang and I (1937)

| Date Completed | 1937 |

| Medium | Oil on Board |

| Dimensions | 40 cm x 28 cm |

| Currently Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York |

This artwork was among the pieces that most intrigued André Breton, the creator of the Surrealist movement when it premiered during Kahlo’s show in 1938 in Julien Levy’s gallery in New York. The painting in the New York exhibition is a self-portrait of the painter and her pet monkey, Fulang-Chang, who serves as a proxy for the babies that she and Rivera were unable to conceive. The portrait’s character layout reflects her fascination with Renaissance artworks of the Madonna and Child. Following the New York show, a secondary frame with a mirror was installed.

The subsequent insertion of the mirror is a statement welcoming the spectator inside the artwork: it was during her months detained at home following her accident that she first started producing portraiture, digging further into her mind by staring at herself closely at her reflection.

When viewed from this angle, the addition of the mirror provides a surprisingly personal glimpse into both the painter’s artistic processes and her inner reflection. Several of Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits feature primates, dogs, and birds, all of which she owned as companions.

Little spider monkeys, like those owned by Kahlo, have been thought to represent Satan, blasphemy, and idolatry since the Medieval Era, eventually coming to symbolize the downfall of humanity, depravity, and the epitome of desire. In the past, these primates were represented as a warning about the perils of obsessive affection and humanity’s basic inclinations.

In artworks from both 1939 and 1940, Kahlo is seen with her monkey. In a second rendition, completed in 1945, Kahlo depicts her monkey as well as her dog. This small canine, who frequently accompanies the painter, is named after a legendary Aztec god believed to symbolize thunder and destruction, as well as the twin of Quetzalcoatl, both of whom had explored the underworld. All of these images, notably Fulang-Chang and I, have ‘umbilical’ cords wrapped around Kahlo’s and the creatures’ throats.

Kahlo is the Madonna, and her dogs take on the role of the sacred (but deeply allegorical) child she yearns for.

The Suicide of Dorothy Hale (1938)

| Date Completed | 1938 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 49 cm x 60 cm |

| Currently Housed | Phoenix Art Museum |

Dorothy Hale was a showgirl from the United States. She had a few failed romances and her business was faltering when her spouse was killed in a car crash. She killed herself on the 21st of October, 1938, because she was in serious monetary difficulty and had to rely on the generosity of her affluent acquaintances. She leaped out the top balcony of her luxurious condominium suite in New York, wearing her favorite black gown and a bouquet of tiny yellow flowers.

Clare Boothe Luce, Dorothy’s close, personal friend and lover of Frida Kahlo, as well as the founder of the magazine “Vanity Fair,” contracted Kahlo to paint a memory picture of their departed common friend for $400 almost instantly.

Clare wanted to present this painting as a tribute to Dorothy’s bereaved mother. She assumed Frida Kahlo would create a standard picture of Dorothy to place over the mantle.

Clare was horrified when the picture came in August 1939 and was opened. She considered burning it, but her companions persuaded her not to. This picture is one of the most frightening paintings by Frida Kahlo and one of her most contentious works, depicting every stage of Hale’s death.

It depicts Hale poised on the ledge, plummeting to her demise, and then laying on the bloodied sidewalk beneath. Clare donated the picture to Frank Crowninshield, whose child handed it back to Clare’s family when Frank died. After that, the painting was stored for years. It was privately presented to the Phoenix Art Museum and is now on exhibit there.

Kahlo was in profound sadness and contemplating suicide at the time she produced this work, having recently separated from Diego. Kahlo’s sympathy for women brought to desperation by male abandonment may be shown in this artwork.

What the Water Gave Me (1938)

| Date Completed | 1938 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 91 cm x 70 cm |

| Currently Housed | Private Collection |

The majority of Kahlo’s figure is concealed in this artwork. We are presented with the plug side of the tub, as well as the creator’s toes, which is uncommon. Additionally, Kahlo has a bird’s-eye viewpoint and gazes from above on the water. Inside the water, Kahlo creates another self-portrait, wherein the more typical face image is substituted with a slew of symbolism and recurrent themes. Pictures of her family, native Tehuana clothing, a pierced conch, a lifeless bird, two female partners, a corpse, a collapsing tower, a vessel setting sail, and a lady sinking can be noted in this artwork.

This piece was published in Breton’s publication about Surrealism and painting, and Hayden Herrera writes in her book about Kahlo that the painter herself thought this piece was exceptional.

The characters and things floating in the sea of Frida Kahlo’s painting form an at once wonderful and real-world of recollection, reminiscent of the tapestries style artwork of Renaissance artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Kahlo stated that it was a sorrowful painting that lamented the absence of her youth. Maybe the choked person in the center represents Kahlo’s inner emotional sufferings. The painter was cognizant of the psychological ramifications of her works.

In a conversation with Herrera, Kahlo expressed “the viewpoint of oneself that is portrayed in this picture” in “a prolonged metaphysical dialogue.” Her concept was about the picture of oneself that you have since you don’t see your mind.

The brain is something that looks but can be observed. It is what one takes along with them to view life. In this painting, the creator’s head is so properly substituted by the internal ideas that dominate her brain. A labia-like blossom and a clump of body hair are depicted between Kahlo’s thighs, in addition to a depiction of death by strangling in the center of the water.

The art is extremely sensual, but it also demonstrates an obsession with death and misery. The tub subject in art has been prominent since Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat and has been used by a variety of artists, including Tracey Emin and Francesca Woodman.

The Two Fridas (1939)

| Date Completed | 1939 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 174 cm x 173 cm |

| Currently Housed | Museum of Modern Art |

This double self-portrait is one of Frida Kahlo’s most famous paintings, and it represents the painter’s inner anguish after her separation from Rivera. The painter is seen on the side in contemporary European clothing, donning the outfit she wore at her wedding to Rivera. Given Rivera’s intense patriotism during their union, Kahlo grew progressively intrigued in her indigenous heritage and decided to study indigenous Mexican clothing, which she displays in the image on the right. It is the Mexican version of Kahlo that is holding a pendant with a picture of Rivera.

The turbulent skies in the distance, as well as the illustrator’s wounded heart – a core icon of Christianity as well as an Aztec ceremonial offering – emphasize Kahlo’s inner anguish and bodily suffering.

Meaningful motifs in Kahlo’s paintings typically have several levels of significance; the recurring theme of bleeding signifies both spiritual and bodily anguish, as well as the painter’s conflicted approach toward conventional ideas of gender and reproduction.

Despite the fact that both figures’ hearts are visible, the female in the white European costume appears to have had her heart separated, and the vein that flows from her heart is severed and gushing. The vein that flows from her Tehuana-costumed chest is still intact since it is linked to a tiny picture of Diego as a youngster. While Kahlo’s heart stays unchanged in the Mexican garment, the Continental Kahlo, estranged from her lover Diego, spills freely upon her garment.

The Two Fridas is not just one of Kahlo’s most famous paintings, but it is also her biggest piece.

Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940)

| Date Completed | 1940 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 40 cm x 28 cm |

| Currently Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York |

The artist is shown as an ambiguous form in this self-portrait. Historians interpret this action as a combative reaction to Rivera’s separation request, reflecting her wounded sense of feminine honor and identity for her relationship’s failings. Her manly clothing also recalls early family photos in which Kahlo decided to wear a blazer. Kahlo’s individuality is also shown through her cut hair.

She has one severed plait in her left hand and several locks of hair on the ground. Severing a plait represents a renunciation of childhood and purity, but it may also be interpreted as the severing of a connecting chord (perhaps umbilical) that unites two individuals or two lifestyles. In any case, braids were an important part of Kahlo’s persona as the customary La Mexicana, and by chopping them off, she dismissed a part of her old self.

The tresses scattered over the ground recall a former self-portrait created by the Mexican legendary character La Llorona, who is today stripped of her feminine traits.

As the abandoned threads of tresses grow active at her toes, Kahlo holds a pair of scissors; the locks seem to have a mind of their own as they spiral across the carpet and across the feet of her seat. Above her somber picture, Kahlo wrote the words and melody of a ballad that says brutally, “Look, if I adored you it was for your tresses, but that you are bald, I don’t want you any longer,” affirming Kahlo’s own condemnation and renunciation of her feminine duties.

In 1997, photographer Elina Brotherus captured wedding pictures, most likely in tribute to Kahlo’s artwork. Brotherus cut her hair short for her wedding, the remnants of which her future husband clutches in his palms.

The gesture of chopping one’s locks as a sign of a turning point occurs in the works of other female painters as well, including Rebecca Horn and Francesca Woodman.

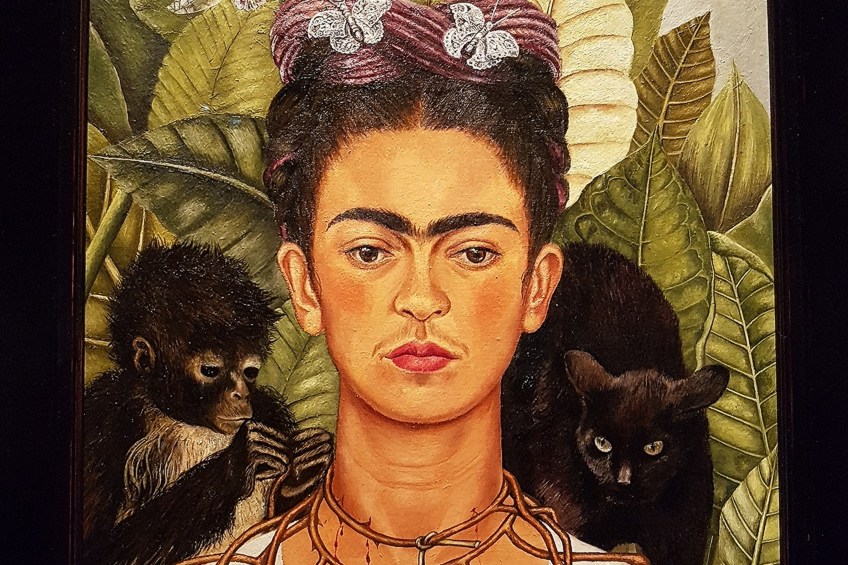

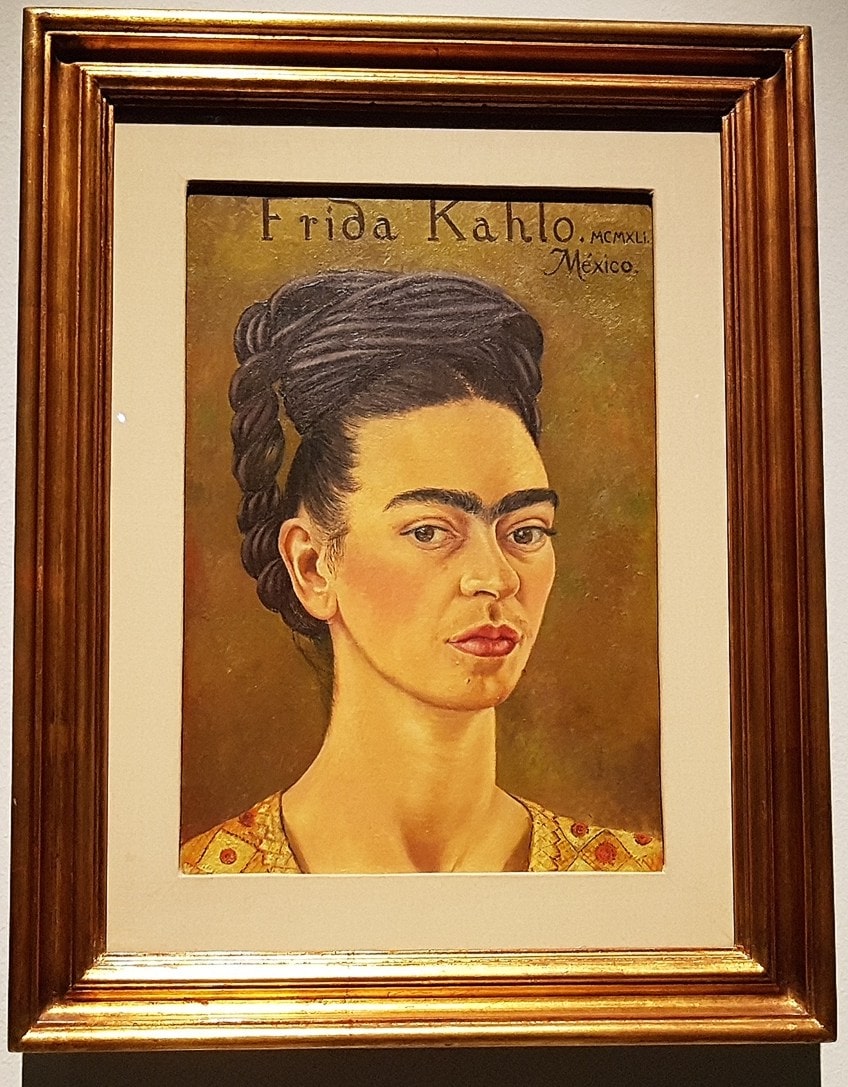

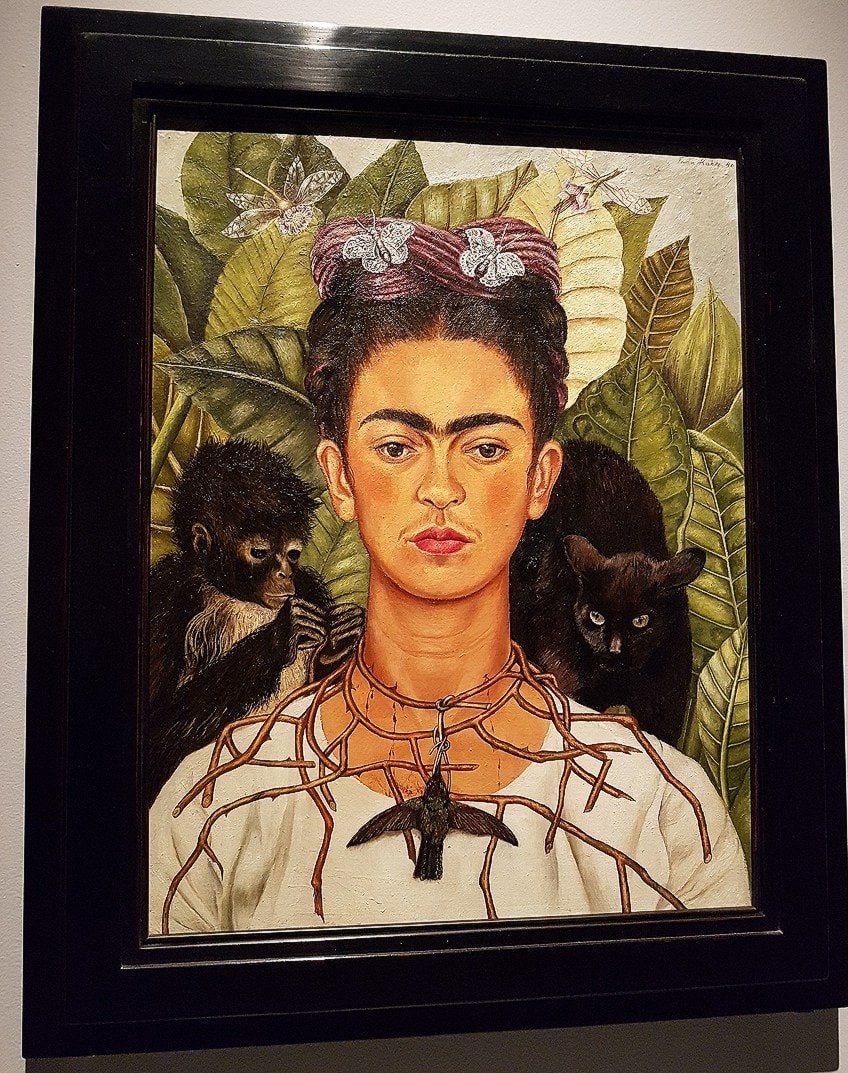

Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940)

| Date Completed | 1940 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 47 cm x 61 cm |

| Currently Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York |

Kahlo’s forward stance and external gaze in this self-portrait engage and confront the observer. The painter displays Christ’s unraveling garland as a pendant that grinds into her throat, representing her identity as a Christian saint and the lasting anguish she felt after her broken wedding. A deceased bird swings in the middle of her pendant, a sign in Mexican folklore custom of fortune charms for romantic love.

A black cat, representing ill fortune and tragedy, kneels below her shoulder, and a monkey, a present from Rivera, is placed to her side.

Kahlo regularly used plants and wildlife in the backdrop of her bust-length portrait to generate a small, cramped environment, utilizing wildlife as a motif to evaluate and compare the relationship between feminine fecundity and the desolate and macabre iconography of the forefront. The symbolism of a ‘deceased’ hummingbird, which is often a signal of great prosperity, is to be inverted. Kahlo, who longs for freedom, is bothered and worried by the reality that the insects in her tresses are too fragile to go far and that the dead animal about her throat has become an impediment, encroached upon by the neighboring cat.

It appears that the artwork depicts the artist’s disappointments by being unable to directly communicate complicated inner sentiments.

The Broken Column (1944)

| Date Completed | 1944 |

| Medium | Oil on Masonite |

| Dimensions | 39 cm x 30 cm |

| Currently Housed | Dolores Olmedo Collection, Mexico |

This painting is an especially poignant depiction of Kahlo’s mental and bodily anguish. Hayden Herrera, the artist’s biographer, states of this work, “A fissure like a quake crack breaks her in two.” The exposed body alludes to surgeries and Frida’s fear that she might fall to pieces if she didn’t wear her steel girdle.

The artist’s disintegrating spine has been replaced by a shattered ionic column, and jagged metal nails puncture her torso. This implanted column’s harsh coldness echoes the metal rod that entered her belly and uterus during her accident. More broadly, the now-demolished architectural element conjures up images of the feminine body’s strength and frailty. Aside from its physical proportions, the fabric draped over Kahlo’s hips is reminiscent of Christ’s loincloth.

Furthermore, Kahlo shows her scars as if she were a Christian saint; by identifying with Saint Sebastian, she combines bodily agony, openness, and eroticism to convey the idea of psychological anguish.

Tears stream down the artist’s cheeks, as they do in many Mexican portrayals of the Madonna; her eyes look out beyond the picture as if surrendering the body and calling the soul. As a consequence of portrayals like this one, Kahlo is now regarded as a Magical Realist. Her eyes remain constant and genuine, while the remainder of the image is fanciful.

The artwork is not particularly preoccupied with the functioning of the unconscious or illogical dissonances, which are more common in Surrealist artworks. The Magic Realism school was increasingly fashionable in Latin America (particularly among authors such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez), and scholars have included Kahlo in it posthumously.

The concept of being injured in the manner shown in this painting is known in Spanish as “chingada”.

This term has a variety of interconnected connotations and notions, such as being injured, damaged, ripped open, or misled. The term is derived from the verb for penetrating and denotes masculine dominance over the feminine. It relates to the victim’s position. Rebecca Horn’s 1970 concert and sculpture piece Unicorn was most likely prompted by the artwork.

Horn wanders nude in an agricultural plain in the work, her torso wrapped in a cloth bodice that looks very comparable to that donned by Kahlo in The Broken Column. The upright, sky-reaching column in the work by the performance artist, on the other hand, is attached to her skull rather than implanted into her bosom.

The presentation has a mythological and religious feel to it, akin to Kahlo’s picture, yet the pillar is complete and powerful again, possibly paying respect to Kahlo’s tenacity and creative accomplishment.

Without Hope (1945)

| Date Completed | 1945 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 28 cm x 36 cm |

| Currently Housed | Collection of Dolores Olmedo, Mexico |

Kahlo was immobile for most of her life due to chronic agony and many procedures as a consequence of serious injuries acquired in a terrible bus accident in 1925, as well as numerous diseases. The painting was completed in 1945, following her most recent episode of sickness, which left her gaunt and emaciated. Kahlo was administered a ‘force-feeding’ regimen of fatty pureed foods, which was given to her every two hours.

The picture portrays a sickly Kahlo, with tears in her eyes, laying in bed amid the dead barren desert, lit up by both the sun and the moon. In Aztec tradition, the sun represents human sacrifices, and Kahlo feels as though she has been slaughtered. The moon signifies women, maybe the femininity stripped away by her miscarriage, another effect of the tragic tragedy while she was in her youth. She is lying under white medical blankets embossed with tiny organisms, which represent the persistent diseases that have infected her system.

In many paintings by Frida Kahlo, her look is calm, as if she is reconciled to the suffering and bearing it. Yet, in this painting, all optimism and patience appear to be lost.

Her arms are bound beneath the blankets, and she has little control over her situation. A gigantic funnel pouring into her lips rises above her torso, a horrific concoction of fish guts, leaking corpses, and other grotesque stuff heaped and spilling from above. The huge wooden panel built by her father to allow Kahlo to create while immobile has evolved into the framework that holds the funnels that nourish her. A typical Mexican sugar head with Frida’s moniker across the brow sits atop the rotten food mound, in accordance with the Mexican custom of the Day of the Dead, which honors those who have died. This is just another striking example of Kahlo’s dismal condition.

“Not the slightest hope exists for me…everything flows in rhythm with what the stomach carries,” is written on the reverse of the artwork.

The Wounded Deer (1946)

| Date Completed | 1946 |

| Medium | Oil on Masonite |

| Dimensions | 30 cm x 22 cm |

| Currently Housed | Private Collection |

The Wounded Deer, a 1946 artwork, expands on both the concept of chingada and the St. Sebastian subject, which was previously examined in The Broken Column. In a woodland meadow, the naïve Kahlo, hybridization of a stag and a female, is injured and hemorrhaging, encroached upon, and pursued. The painter ensures her survival by glancing squarely at the spectator, despite the fact that the shafts would gradually kill her.

The painter wore a pearl earring as if to emphasize the conflict she experiences between her community life and her yearning to dwell more freely beside the wilderness.

Kahlo portrays herself as a full-bodied buck with enormous racks and genitalia, rather than a dainty and sweet fawn. It would not only imply, as does her matched look in early family pictures, that Kahlo is intrigued in mixing the genders to form an androgenous character, but it also demonstrates that she tried to identify herself with the other great painters of history, the majority of whom were males.

The limb under the stag’s legs is symbolic of the palms fronds put beneath Jesus’ feet when he landed in Jerusalem. From this moment until her death, Kahlo identified with the Catholic character of Saint Sebastian. She finished a painting of herself with eleven darts piercing her flesh in 1953. Likewise, the artist Louise Bourgeois, who was similarly concerned in the representation of agony, utilized St Sebastian as a recurring figure in her work.

She originally represented the subject in 1947 as an idealized sequence of shapes, hardly identifiable as a portrait; created using watercolors and pencils on pink paper, but later fashioned an apparent pink fabric sculpture of the figure, wounded with darts, suffering under assault and terrified, similar to Kahlo.

Weeping Coconuts (1951)

| Date Completed | 1951 |

| Medium | Oil on Board |

| Dimensions | 23 cm x 30 cm |

| Currently Housed | Los Angeles County Museum of Art |

Frida Kahlo’s health worsened at the close of her life to the extent where she no longer desired to depict herself through self-portraits and was also practically constrained to working on a smaller scale. She shifted her focus to still paintings since it was more suitable for the smaller size and demanded less accuracy. Despite the shift in subject from her well-known figurative works, her still lifes managed to communicate a wide variety of emotions.

Weeping Coconuts is a still life composed of citrus fruits, a piece of papaya, and two coconuts set against a plain green backdrop. There’s also a tiny flag put in lime that says “Painted with much devotion.” Frida Kahlo produced this as a present for Elena Border, but she gave it back to the artist since she didn’t like the lifeless, gloomy colors and wished to swap it for another piece. However, Kahlo covered Elena’s name and resold the picture without providing her a replacement. The two coconuts that appear to be sobbing are the composition’s focal point, as the title indicates.

The coconuts become representations of melancholy, with the marks on their skin resembling weeping eyes.

Frida Kahlo’s beauty and skill to paint began to degrade as her health deteriorated, and she no longer desired to depict herself, so she selected these coconuts as an alternate medium for conveying her agony at her destiny. The colors are flatter and heavier than in Frida’s previous paintings, and the arrangement emphasizes solitude and sorrow.

The brushwork, which lacks the accuracy and subtlety distinctive of Kahlo’s paintings, provides more indications of her failing health. This juxtaposition is especially striking when compared to other paintings from the same year. Ultimately, this painting captures Kahlo’s tremendous anger and grief at being confined in her illness-ridden frame, which she eventually rejected as creative inspiration in favor of commonplace items like the fruit and coconuts she depicts in Weeping Coconuts.

And that brings us to the end of our list of important Frida Kahlo paintings. We have learned how many of Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits contained symbols of her struggles with physical ailments and uncertain roles as a woman and Mexican. Frida Kahlo’s original paintings have done much to bring light to Mexican culture and the plight of women in general.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Frida Kahlo Known For?

Frida Kahlo is recognized as a hero because of her unique personality and diversified upbringing. She has become a figure of feminine strength, known for being a lover of Mexico and her history, and persistence in the face of adversity. Above all, she was a sincere person who held fast in her views. Frida Kahlo’s original paintings were often deeply personal in nature, blending truth and fantasy.

What Was Frida Kahlo’s Art Style?

Paintings by Frida Kahlo displayed very mixed influences. Frida Kahlo’s famous paintings mixed elements of Naive art with Surrealism and Modern Art. She was also regarded as one of the artists of Magical Surrealism.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Frida Kahlo Paintings – Looking at Frida Kahlo’s Most Famous Paintings.” Art in Context. October 19, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/frida-kahlo-paintings/

Meyer, I. (2021, 19 October). Frida Kahlo Paintings – Looking at Frida Kahlo’s Most Famous Paintings. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/frida-kahlo-paintings/

Meyer, Isabella. “Frida Kahlo Paintings – Looking at Frida Kahlo’s Most Famous Paintings.” Art in Context, October 19, 2021. https://artincontext.org/frida-kahlo-paintings/.