Ansel Adams – A Look at the Life of Photographer Ansel Adams

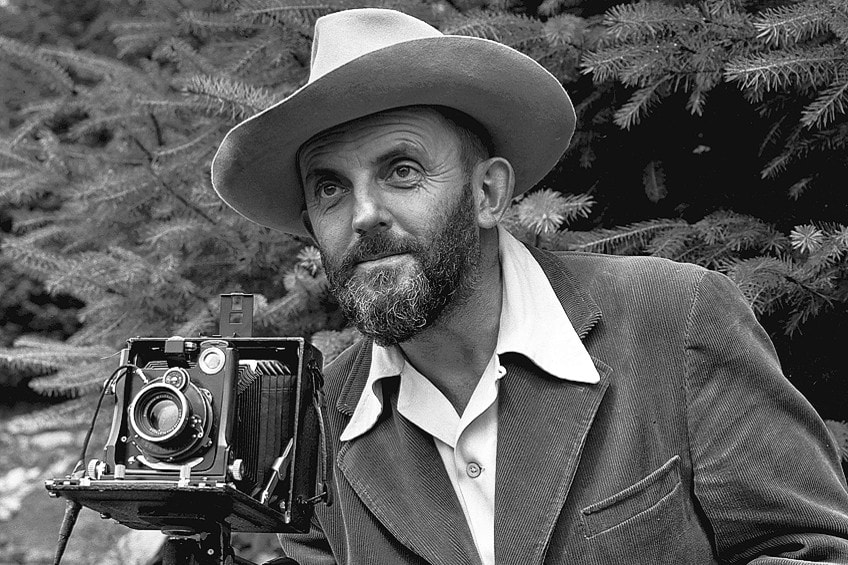

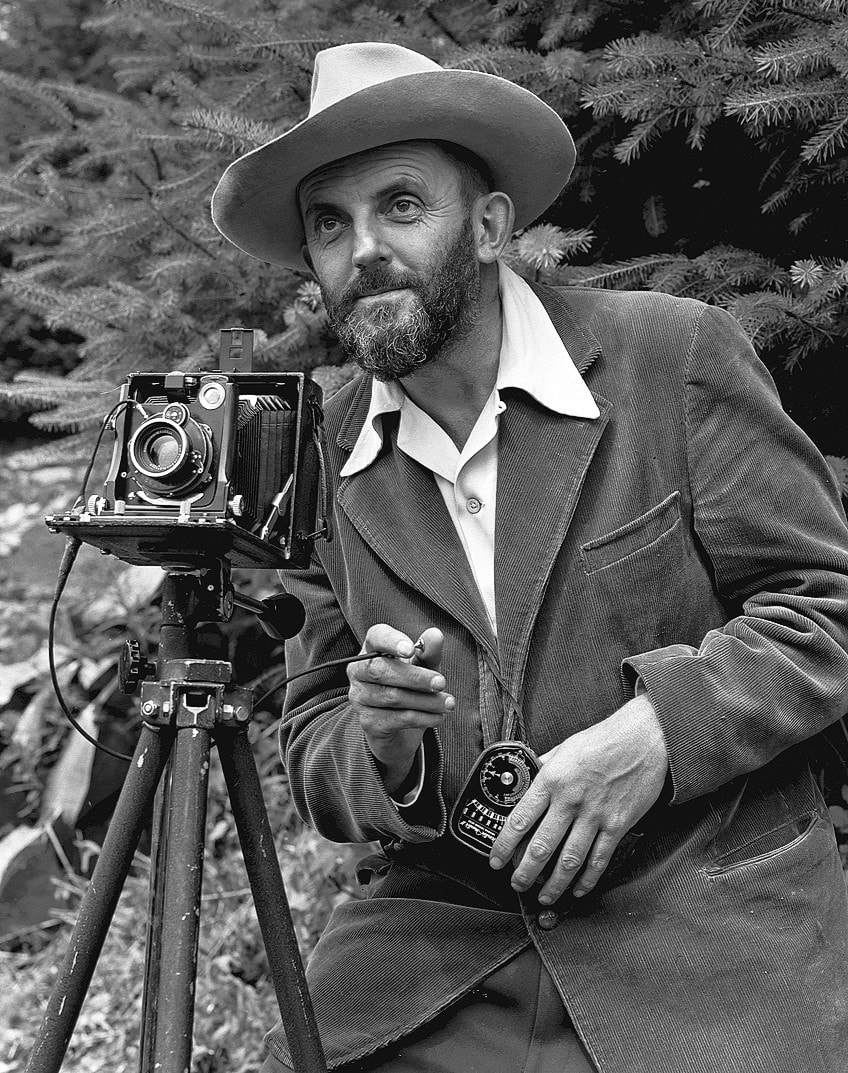

American photographer Ansel Adams is one of the most revered figures of landscape photography. Throughout his roughly 60-year career as a fine art and commercial photographer, Adams explored and recorded the grandeur of nature. His clever techniques helped elevate landscape photography and have influenced contemporary image technology.

Ansel Adams’ American Aperture

| Date of Birth | 20 February 1902 |

| Date of Death | 22 April 1984 |

| Place of Birth | San Francisco, United States |

| Associated Art Movements | Pure Photography |

| Genre / Style | Photography |

| Mediums Used | Photography |

| Dominant Themes | Landscape, Yosemite, Half Dome, National Parks, Patriotism |

Ansel Adams’ photography is typified by punchy black and white images that are ubiquitous and have become standards in the contemporary photographic world. They helped pioneer a formalized approach to black and white darkroom photography.

The Zone System, a technique that earned Adams a worldwide reputation is a core component of digital photography.

Ansel Adams’ Biography

Born into a wealthy upper-class family in San Francisco in 1902, Adams was an only child. His mature parents doted on him, and he was quite a hyperactive child. So much so that he was asked to leave school when he was in the 8th grade. He was the class clown and had a short attention span, so his parents arranged private tutoring.

His father bought him a piano and he began piano lessons. By the age of 12, he was receiving composition lessons and becoming increasingly serious about his musical training, which had shifted his state of mind. He was no longer the unruly child but began writing about his experience and his physical environment.

He also began taking photographs of downtown San Francisco. He started reading photography magazines and joined local photography clubs. At first, he used a five-by-seven camera that belonged to his family.

In 1916, upon seeing his enthusiasm, his father bought him his very own which was a Kodax Brownie Box Camera.

Ansel Adams’ Yosemite

Right after he got his new camera in 1916, his family took him on his first visit to Yosemite National Park. There is a photograph of the Adams family taken on this trip. 14-year-old Ansel with his father on his left, his mother and aunt on his right.

The Ansel Adams biography states that he fell in love with photography and Yosemite during this first trip.

Ansel Adams initially took family snapshots to make photo albums in, which he and his father would paste photographs Ansel had taken, to document their vacations. Like any family album, it included pictures of his family members. It was clear that at this point, Adams was making some sort of visual diary, not art.

But over time, as Adams continued taking his Brownie box camera on family trips to the mountains, he began focusing on the landscape. He felt the “rocks of Yosemite are the very heart of nature speaking to us” and he did not take it lightly.

He would frequently return to Yosemite, which became the primary place where he nurtured his love for nature and photography.

Half Dome

Adams’ early photographs had enthusiasm but left much to be desired, though there are signs that he was merely limited by the camera technology available to him in the early 20th century. His earliest photographs taken on his Brownie camera show that despite his rudimentary equipment and limited experience, he was a photographer truly at play.

By depicting a deliberately obscured subject, Adams was already experimenting with composition and grappling with his capabilities and limitations as a photographer.

In the album, the Half Dome pictures are organized from west to east, showing that even at 14, Ansel was considering the curation and logic of his work. Half Dome was important to Adams as it was a photographer’s subject. As he became entrenched in the landscape photography scene, he began to learn through the company he kept.

As this particular Half Dome had been famously photographed by numerous photographers, Ansel tackled it often and came to be associated with it, so much so we frequently use the phrase “Ansel Adams’ Yosemite photographs”.

A Photographer Is Born

Ansel Adams preferred the term “taking photographs” to “making photographs”. He continued “making” photographs and using the photo diary format and, by the time Adams was 19 years old, his first formal photographs were being published. At 20, he became a caretaker at the Sierra Club in Yosemite Valley.

He started to sell prints at a gallery called Best’s Studio in Yosemite Valley, which was owned by his girlfriend Virginia’s family.

Adams went from being a tourist of Yosemite Park to being an expert and mountaineer, exploring Yosemite and the Sierra on foot. He began documenting the wilderness. He even got a borough to carry his equipment, traveling with mentors so that he could learn about the flora and fauna.

Adams was improving through trial and error. “Mobile Sang Peak” (1917) and “Mount Florence Through the Trees” (1923) show the trajectory of his developing eye for composition and detail, but he was still finding a style.

Visualization

The 10th of April 1927 was significant for Ansel Adams. Something occurred during an excursion he took to Half Dome in Yosemite National Park with his future wife Virginia amongst others. He had been making his way onto the so-called “diving board” where hikers go to view a facet of the huge granite dome.

When Adams stood from a bleak angle, looking up at Half Dome with the camera on a tripod, he had a vision of what he wanted the image to look like. According to him, this was the first time he used the technique of “visualization”.

With this vision in mind, Adams applied a yellow filter first, which looked ordinary through the camera lens and did not have the drama of his vision. Then he set the exposure to F/22 and applied a red filter, exposing the plate for five seconds. This made the image of the sky and rock appear darker. The darkened sky charges the image with drama and intensity. Ansel considered Monolith, the Face of Half Dome (1927) to be a breakthrough because of this technique.

Ansel Adams’ photography then became a means of manifesting the picture in his mind’s eye. First, the photographer composed the image in his mind. Then he thought of the tonal values of the final print. Because he was seeking the closest equivalent to his vision, Adams became focused on technique.

Adams wanted the image to emerge as visualized by the artist before making the image. The technique would be useful because it could enable near-perfect negatives. When Monolith, the Face of Half Dome was being developed, and it corresponded with his internal visualization, he became devoted to this way of working.

In this way, Adams began experimenting with technicality and the possibilities of the medium.

In 1928, Adams had married Virginia, finally given up on a career as a concert pianist, and became the official photographer for the Sierra Club and, in 1930, the Yosemite National Park. His images appeared in souvenirs, booklets, and advertising. The time he spent working in the advertising field taught him about making clear images that communicated a strong message.

Signature Style

Adams’ compositions are measured. He thought of placemen and usually took only one image, sometimes two for insurance, but the two were often identical. Such was his level of precision and confidence in his craft. He had to make instinctive decisions as a photographer and became comfortable working under the notion of frozen time.

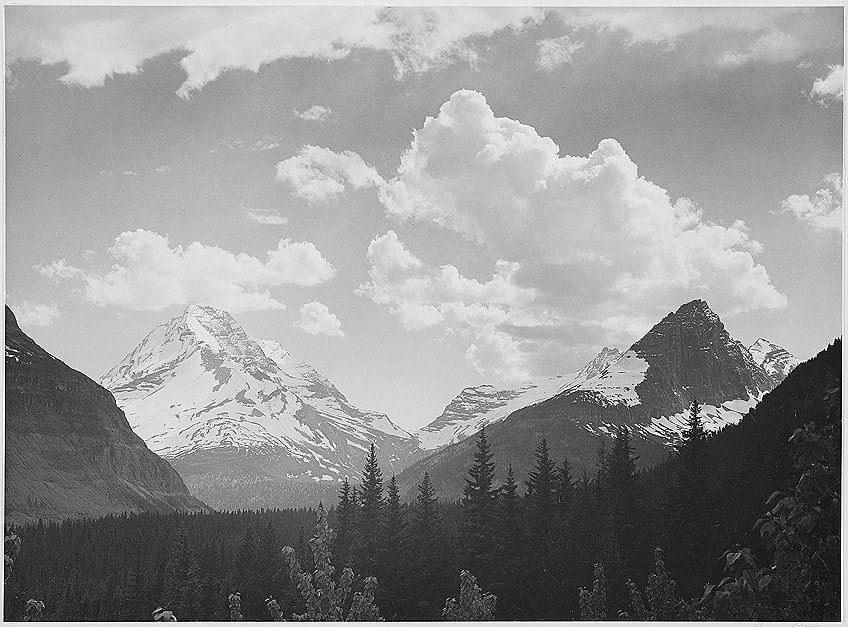

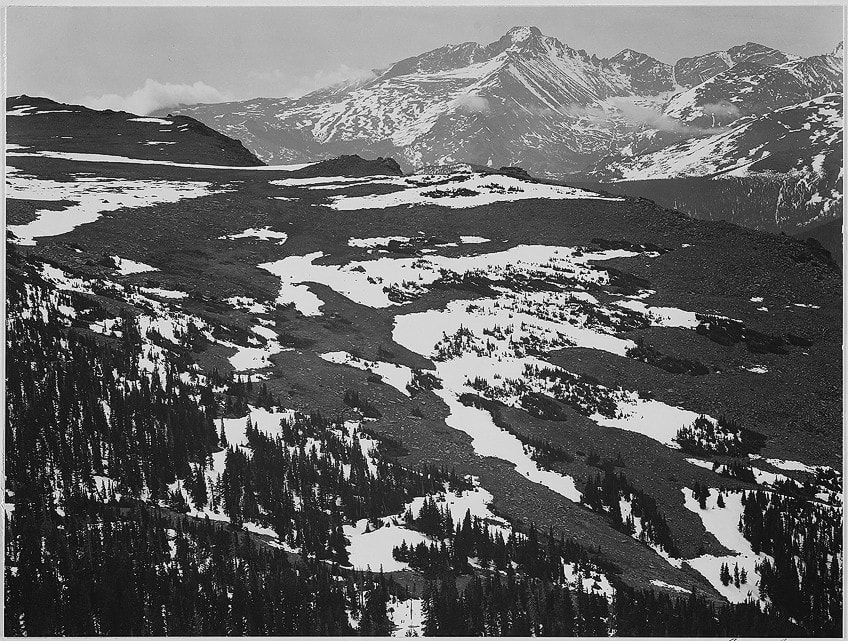

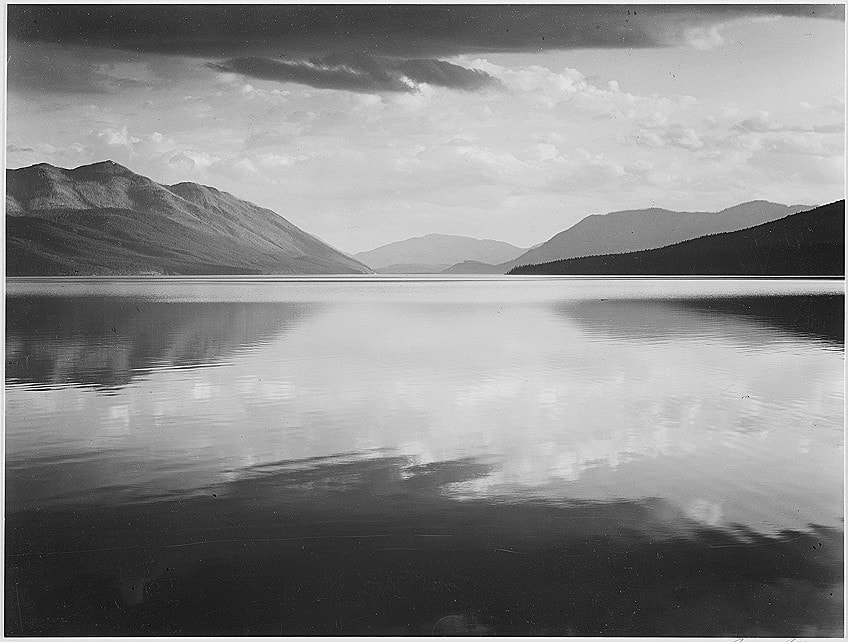

Some of the characteristics of Ansel Adams’ photography includes a panoramic sweep of a landscape and an omniscient viewpoint.

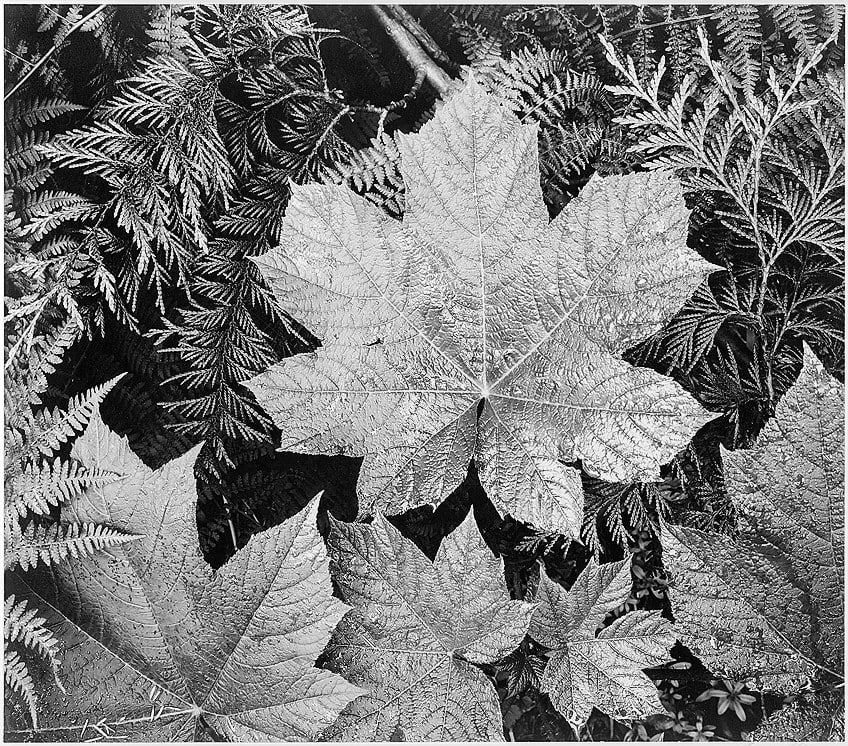

He often placed the horizon line high in the frame to convey scale. His work portrays the atmosphere and scale of those mountainous landscapes. A strong “S” curve often shows up in his landscapes as a guiding line that creates a sense of movement. Ansel Adams often uses the river to achieve this effect.

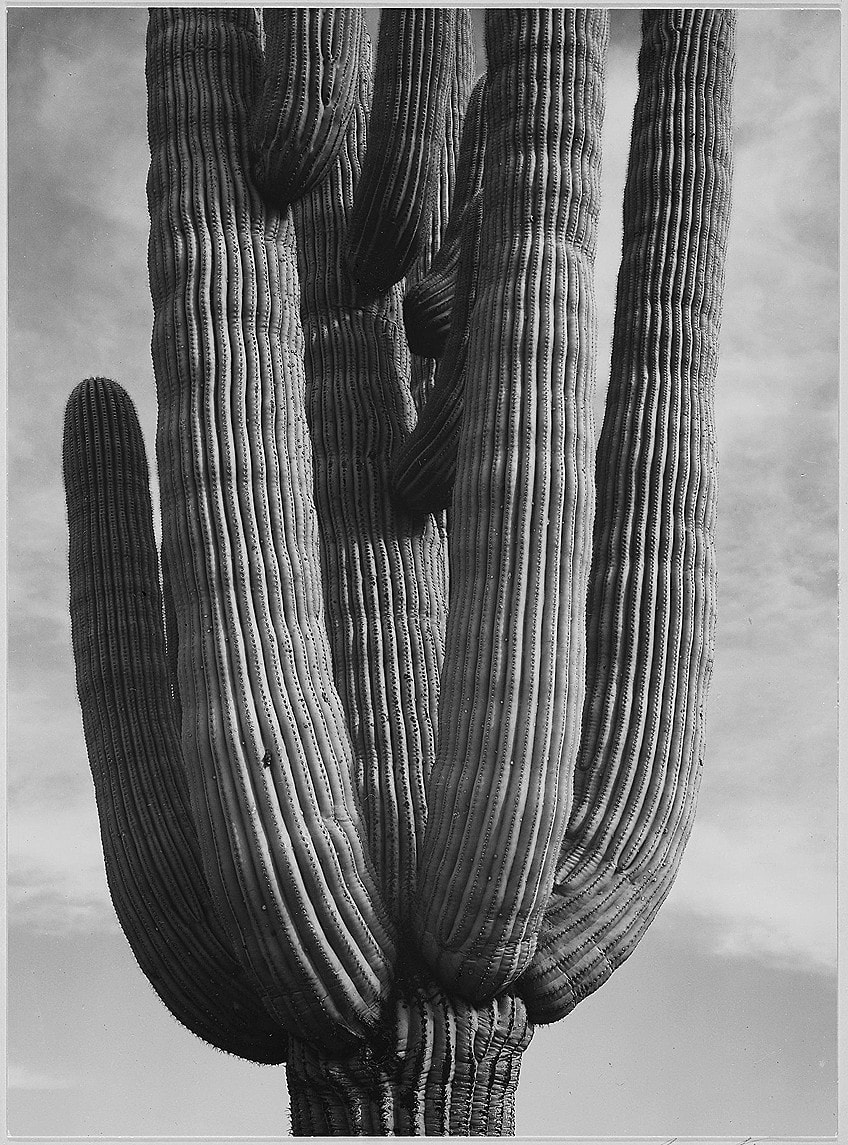

The subjects of Ansel Adams’ photography seem to be bursting out of the frame. His tight framing and careful cropping left little margin around the edges of photographs, making his subjects feel like they were looming. He used interconnecting lines that framed a subject or parallel lines that created depth in the composition.

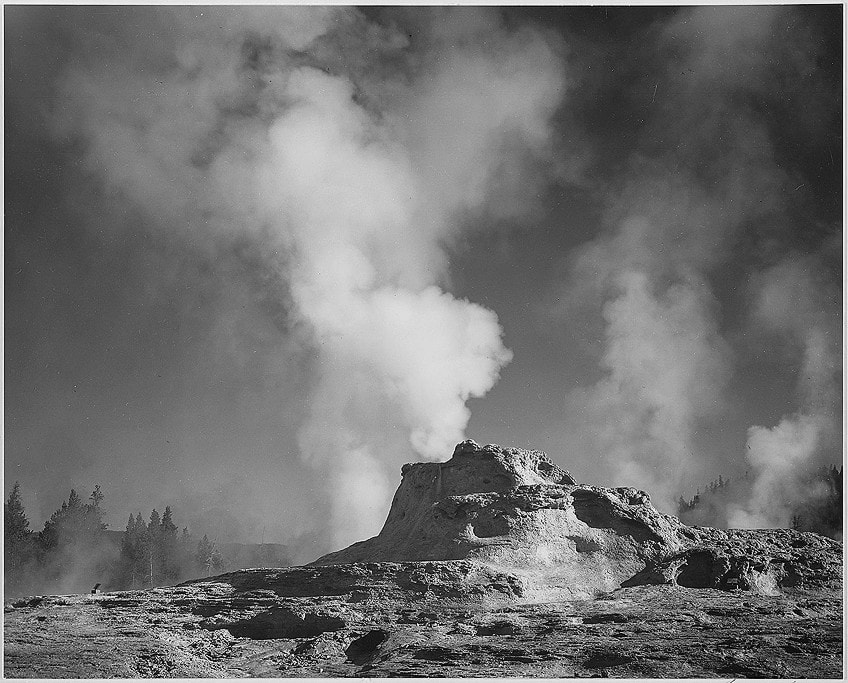

Whether it was the surface of massive mountains or the details on a tiny tree, the strange textures of the natural world were an important compositional device in Ansel Adams’ photography. He captured wood, stone, snow, and a range of other textures, highlighting detail to give the illusion of substance and often enhancing the scale of his photographs.

In Ansel Adams’ photographs, we see storm clouds shrouding mountain peaks or light summer rain. Adams preferred dramatic scenery and often shot towards or just after a storm. As such, many of the titles of his images include the word “storm”. His visual style used weather effects to heighten the operatic qualities of the picture.

Adams’ instinctive use of tonal balance and contrast gave his images an engaging forcefulness. Shining passages of light were interrupted or complemented by areas of dense darkness. His images had a full tonal range from white to black, which made them look balanced. Adams used shadow density and light as a medium of revelation and enhanced lighting, causing areas of the frame to fall into shadow. He deliberately engaged negative space in his images.

Ansel Adams seemed to prefer monochromatic images. He found green and blue boring, even unsightly on print. What he saw in nature was far more complex. Black and white allowed for subtlety, making shadows more dramatic. By shooting in black and white, he manipulated reality and placed the viewer closer to the fantasy realm.

Though rooted in nature, Adams’ images represent an idealized heroic version of what existed. His photographs depict not what he saw but what he felt. He admitted this notion was romantic, but his dramatic Southern Sierra scenes were a testament to his special access to nature untouched by humans, which gave his images a legendary quality.

Pure Photography

Ansel Adams’ success properly arrived in the mid-1920s and early 1930s. He was shooting at new locations and, while in New Mexico, he befriended many of the artists from Alfred Stieglitz’s entourage including Paul Strand and Georgia O’Keefe. Strand would influence Adams enormously and encourage him to sharpen his craft. In 1931, Adams had his first solo museum show at the Smithsonian, which was extremely successful, garnering stellar reviews. The next year, he had a group exhibition at the D Young Museum in San Francisco.

In 1932, at the height of his career, Adams’ joined some other bay area photographers in a new movement that distanced itself from Pictorialism, which was seen as an imitation of painting.

Adams had experimented with Pictorialism techniques before. As aforementioned, he had used soft focus as well as other techniques such as etching and the bromoil process. Adams now had access to new camera technology and techniques, which allowed him to achieve new effects.

Pure Photography stood against the staged, false idea of life created by Pictorialism, which was the winning style of art photography in the early 1900s. These young artists wanted unfettered photography to be accepted as an art form. Their manifesto for what they called Pure Photography was contradictory to some degree, however, because they still used manipulation techniques, albeit to different ends.

Theirs was to enhance the photograph’s photographic quality by producing glossy, crisp images. They wanted to depict objects with a minimum of fuss – as they were rather than a romantic notion of them. The objective was a clear image of the subject using light to capture each natural texture.

This group of photographers, based on the west coast, called themselves Group F/64 because they preferred to shoot F/64, which is a very narrow aperture that keeps the frame sharp by maintaining a good depth of field.

Group F/64’s most famous members included Paul Strand, Edward Weston, and Imogen Cunningham. Group F/64 brought attention to the new southern California school of photographers, but it was also an important part of the history of photography overall.

The Dark Room

Despite being part of the Pure Photography movement, in his books, Ansel Adams maintains that he is not a purist. He was known to spend hours in the darkroom on each print attempting to technically execute his visualizations. Adams thought of the negative as something malleable with numerous possibilities.

He never printed a photograph the same way twice and would rework prints of the same negative to achieve perfect pictures of remarkable tonal veracity. He often said that all the various prints differ the same way each performance does.

Maintaining as much sharp detail throughout the frame as possible, he coaxed contrast in the darkroom, often long after the photograph was taken. He worked on each photo, meticulously dodging and burning all his landscape photos. He did not invent these techniques, nor was he the only artist to experiment with them, but he took to them to another level.

To dodge a photo, he would use an opaque object to block light in a certain area of the frame. As less light developed on that part of the print, it came out darker. To burn a photo, he could use the same object with a little hole in it, adding extra light to a specific area to make it brighter.

These terms “dodge” and “burn” are important tools in contemporary image editing software like Photoshop and have the same function of altering light densities for printing or display processes.

The Zone System

The precise exposure of different elements in the scene was so important to Adams that he developed a technique to ensure he could achieve his visualizations. Together with Fred Archer, Adams developed The Zone System, which ranked values from zero to ten based on how dark or bright they were to appear on the print.

Adams kept a record of important values on the exposure scale, assigning an F-stop or aperture setting for each element in a composition.

With this meticulous technique, a photographer could take polymetric readings that helped capture detail. This enabled accurate estimations of exposure and editing requirements, which meant one could print in a wider range of sizes. Thus, photographers could get a good grip on the look of the image before they even took the picture.

Whether out in the field or in the darkroom, the ability to expose various elements accurately enabled photographers to manipulate the lighting and contrast of a scene. The beautiful rendition of tones allowed Adams to produce portfolios of original prints, which were in themselves works of art.

Adams’ Zone System is still used today for exposure, color grading, and as a base for the modern camera and the way cameras process light.

National Parks and National Identity

In 1940, the Secretary of Interior appointed Adams to photograph the National Parks and Monuments of the United States. A selection would be made from his output and turned into murals for the then-new Washington Department of Interior. Ansel Adams would be paid a modest $5 a day and 4 cents a mile, but it was enough for him to put on hold his commercial work for some months and devote himself to photography and travel. He traveled as far as Alaska and the Pacific Northwest.

The combination of decades of photographic practice and the freedom to focus on photography cemented the hallmark style of Ansel Adams’ photographs, which boasted spectacularly rendered light and detail.

Unfortunately, after just two months of photographing in the National Parks, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and World War II came about. Adams’ gig was canceled, and the mural images were never made. However, Adams continued the project with the idea that he would photograph more beautiful American landscapes to inspire patriotism.

He got a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation to finish his project, which even allowed him to get new equipment. This is when some of his best-known images were made.

Moonrise Over Hernandez

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico (1941) came about while driving up on the highway with his eight-year-old son Michael and friend Cedric Wright. They were on their way back to Santa Fe from a visit with Ansel’s friend the artist Georgia O’Keefe up the valley in New Mexico. Adams was captivated by the scene of the setting sun illuminating the white crosses of the graveyard in Hernandez.

He hastily halted the car, got up on its camera platform, which he had mounted precisely for such moments, and instructed his companions to help him haul out his eight-by-ten-inch camera, tripod, lens, lens board, dark cloth, loaded film holder, and light meter. In the manic rush, the light meter could not be located.

With the November sun rapidly setting behind him, Adams knew he had to act quickly to frame, focus, and capture the view. Evaluating the scene beforehand, he estimated from memory the luminance of the full moon, approximating its exposure setting. Adams released the shutter and, as he was flipping the film to make a second backup negative, the sun had set and the opportunity had passed.

It turned out that a single shot was not a perfect negative, but Adams manipulated the image in the darkroom, amplifying the contrast so that the straight print hardly resembled the edited version. The Zone System made it easier for Adams to manipulate the exposure of solid areas of the print.

In the panoramic sweep of Moonrise, Hernandez, Adams filled the frame with a vast expanse of sky, placed the chapel and cross-filled graveyard in the middle ground within a shrub-filled plain. The moon is suspended above distant clouds and the late afternoon sun dips below the horizon of a low chain of mountains beyond the tiny town of Hernandez in the west.

Of course, none of these features would have appeared as they do in the print. When Adams captured the image, he already knew that he would invent a dark expanse over an otherworldly burial ground in his proof print of Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico. Adams had visualized the finished artwork and wanted to depict Moonrise as it had existed in his mind’s eye. He would continue to print the sky progressively darker with subsequent prints.

From the raw material of the Hernandez landscape, Adams used his darkroom techniques to create an engaging image that borders on magic and mysticism. In this image, Adams drew on over two decades of photographic experience to create what would become his most iconic image. In 1944, it was exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and over the decades, Adams would make over 1300 unique prints of “Moonrise”.

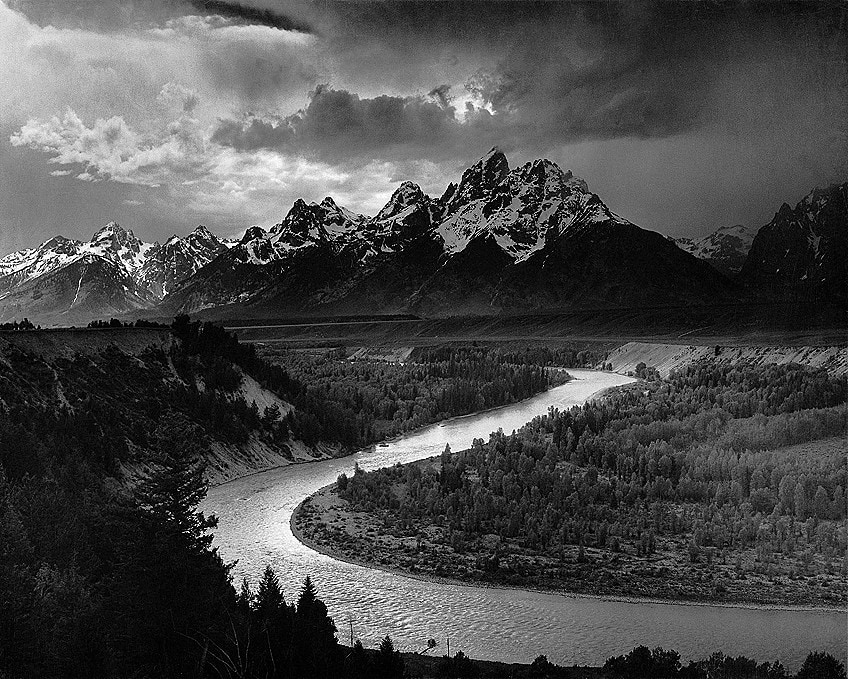

Tetons and the Snake River (1942)

Tetons and the Snake River (1942) is another of his famous images taken while on the road. Whilst Ansel Adams’ photographs often looked like they were made deep within the wilderness, they are shots Adams spotted from the manmade road.

Such was the case in “Tetons and the Snake River”, which was particularly hard to photograph because the sun was facing the wrong direction.

Nonetheless, Adams achieved strong shifts and balance in contrast through his representation of every tonal zone in his system, from zone zero being the black in the shadow of the mountains to zone ten of the light reflecting off the river.

In Tetons and the Snake River, the detailed storm clouds are swathing the shimmering sky, and distant mountains glitter with patches of bright snow on the left-hand side. In the center mid-range, the silvery Snake River makes an “S” curve. The moon glows at the back and the tree-covered banks are detailed with shadows in the immediate foreground.

Adams used stylistic mechanisms to present Tetons and the Snake River as a heroic vision of the American wilderness. He chose a panoramic view because this vantage point imparts a sense of power and authority to his subject.

Adams’ attention and timing, combined with his talent for editing and visual effects, allowed him to capture the spectacularly magical beauty of the national natural world.

Winding Down

When comparing Forest in Yosemite Valley (c. 1920), which was made when the photographer Ansel Adams was about 18 years old, to Aspens, Northern New Mexico (1958), which is part of his mature oeuvre, we see the development from images of a curious young man with a decent eye to the phenomenal quality of a seasoned professional.

But towards the end of his career, photographer Ansel Adams would continue to return to his roots at Half Dome, the subject of his childhood scrapbooks. The last Ansel Adams photographs made in the 1960s showed that he never stopped visualizing Halfdome. In his final Half Dome images, there are no clouds or weather. This photography was as pure as possible. It was the moon, it was Ansel, and it was Half Dome.

After the 1960s, Adams’ photographic output came to an end. He was older then, with deteriorating health. The prospect of hiking up the high Sierra had receded. But he still had the darkroom and would continue to tinker away, through thousands of negatives, reminiscing on the transcendent times he had traversing and transposing the wild west.

A Lasting Legacy

In the 1970s, Adams was commissioned by President Jimmy Carter, making Adams a pioneer in the list of presidential photographers who would include Yoichi Okamoto (1915 – 1985) and Michael Evans (1944 – 2005). In 1974, he had a major retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ansel Adams was an avid conservationist who had lobbied Congress to establish more National Parks. The Ansel Adams Wilderness and Mount Ansel Adams in Yosemite were named after him.

But Adams lived in turbulent times when other photographers considered socio-economic issues to be paramount and criticized his focus on conservation. Influential photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson wrote: “the world is falling to pieces and all Adams and Weston photographs are rocks and trees.”

In hindsight, it could be said that it was the photographer Ansel Adams who was seeing the bigger picture. He showed the earth as more than just rocks and trees and demonstrated that photography was more than just pointing and shooting.

Recommended Reading

Here are some recommended books for those who would love to learn more about Ansel Adams or have a collection of his most brilliant images to look at. Based on Amazon.com ratings, these books will provide more expansive information on what this article has outlined.

Ansel Adams: 400 Photographs (2007) by Ansel Adams and Andrea G. Stillman

This book is a pure compilation of Ansel Adams’ photography presented in chronological order. As the title suggests the book presents hundreds of Ansel Adams photographs which will be a treat for anyone who enjoys images of the natural world. These images include Ansel Adams’ famous early photographs of the High Sierras and Yosemite to his more mature work. Because of its design and binding, it makes for a perfect gift or tabletop piece.

- Presents the full spectrum of Adams' work in a single volume

- Offers the largest available compilation from his photographic career

- Beautifully produced and presented in an attractive landscape trim

The Negative (1995) by Ansel Adams and Robert Baker

Ansel Adams was known for his publication record and knack for transmitting his methods to young photographers. This series has early editions dating back to the 1980s. This book is the second part of Ansel Adams’ acclaimed series of books teaching photography using examples of his own work. Although it has received mixed reviews, the beautiful images in the book are a perfect illustration of Adams’ world-renowned Zone System.

- Over one million copies have already sold

- Distills Adams' knowledge gained through a lifetime in photography

- This classic manual can dramatically improve your photography

Ansel Adams’ biography ended when he was diagnosed with cancer and died in 1984 of congestive heart failure at the age of 82, but his influence is infinite. Today, cameras are common, and more photos are taken, filtered, and posted within half a year than there are stars in the galaxy. Adams’ contribution has influenced a new generation of incidental photographers for whom photo manipulation techniques like dodging and burning are so accessible, they have become virtually transparent.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Would Ansel Adams Think of the Digital Age and Its Ability to Manipulate Photographs?

Because he was so interested in control and adopted any technology that helped him achieve this with great fervor, it would be hard to imagine him not being enthusiastic about digital technology and the possibility to manipulate an image at a pixel level.

Did Ansel Adams Take Color Photographs?

Yes, there are thousands of color Ansel Adams prints. He experimented with this format but found he could not have as much control with color printing. Since he was so invested in the technique and mechanics, the limitations of color photography frustrated him.

Did Ansel Adams Photograph People?

Yes. While he is not known for his portraiture, he did photograph people, which he did not mind. However, Ansel Adams’ photographs depended on control, which complicated the balance between posed and unposed pictures.

Did Ansel Adams Photograph Georgia O’Keeffe?

Yes. In his remarkable impromptu photograph of Georgia O’Keeffe, she is seated and her face, which looks directly at the camera, could be said to resemble a landscape. Adams also photographed O’Keeffe’s husband Alfred Stieglitz in color, with the most subtle light seeping in through a window.

Who Is Dorothea Lange?

Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams were friends and thus shared opportunities and experiences as American photographers. Dorothea Lange was a documentary photographer and photojournalist known for her photographs of the Great Depression, Native American displacement, and post-war concentration camps.

How Much Are Ansel Adams Prints?

At the height of his career, Moonlight could sell for about $350. By 1980, the price had reached $13,000 to $15,000 per print. In today’s market, these prints are routinely sold for up to $30,000 to $50,000. Once his commercial success rocketed, Ansel Adams’ prints fetched such high prices that he decided to sell only to museums and institutions.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Ansel Adams – A Look at the Life of Photographer Ansel Adams.” Art in Context. March 28, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/ansel-adams/

Sincuba, T. (2022, 28 March). Ansel Adams – A Look at the Life of Photographer Ansel Adams. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/ansel-adams/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Ansel Adams – A Look at the Life of Photographer Ansel Adams.” Art in Context, March 28, 2022. https://artincontext.org/ansel-adams/.