Famous Italian Sculptures – A Look at the Top 11 Statues

Italian statues are among the most renowned works of art around the world. Italian sculptors were well-known as some of the greatest artists of their and any other era. Famous Italian sculptures from the Renaissance era are particularly praised for their fine craftsmanship. Below, let’s examine some of the most famous Italian sculptures ever made!

Some of the Most Famous Italian Sculptures

Because of its rich past and, of course, the highly significant Renaissance era, Italy is the site of some of the world’s most spectacular artworks. Italian sculptors such as Michelangelo Buonarotti were inspired by the Bible and human nature as they sculpted magnificent works of art that are still available for visitors and art fans to explore.

These Italian masterpieces have become some of the most famous in the world, with many of them residing in Italy.

Laocoön and His Sons (30 BCE) by Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus

| Artist Name | Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus |

| Date Completed | 30 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 208 |

| Location | Vatican Museums, Vatican City |

The sculpture Laocoön and his Sons, created in the first century, is a massive marble monument housed at the Vatican Museum in Rome. The sculpture is attributed to three sculptors who all contributed to its creation: Polydorus, Athenodoros, and Agesander. The huge statue is based on a Greek mythological narrative and exhibits the Hellenistic enthusiasm for displaying dynamic and dramatic figure groupings that evoke feelings of drama and agony. This is established through the sculpture’s use of aesthetic components such as line, shape, and a focal point in the center, but it also communicates an emotional aspect with intensity.

This sculpture exemplifies Hellenistic ideals, different depictions, and aggressive imagery, all of which make it unique and captivating.

The evolution of Hellenistic art originates from the historical transition that happened after Alexander the Great’s death and after the Romans gained their victory at the Battle of Actium. The Hellenistic period followed Alexander’s rule and represented the beginning of the Roman Empire. The emergence of this era, which lasted from 323 to 146 BCE, was responsible for the resurgence of art that generated drama, intricate compositions, and sorrow or passion.

The sculpture was discovered in Felice De Fredis’ vineyard in 1506. It was handed up to Pope Julius II in March 1506 and placed into his personal possession. The look of misery and the deformation of the faces are significant features of this artwork. It is still debatable whether this item is an original or a reproduction of an older bronze work.

Dying Gaul (22 BCE) by Unknown

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date Completed | 22 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 180 |

| Location | Capitoline Museums, Rome, Italy |

This lovely sculpture has an intriguing narrative in that no one knows who made it. It is assumed, but not proven, that it was sculpted by Epigonus, a Pergamon court sculptor. This is a replica of the bronze original, which is thought to be a lost Hellenistic sculpture commemorating Pergamon’s triumph against the Galatians. This sculpture represents a naked soldier accepting his death as a result of a big slash across his chest.

While this beautiful replica in Rome is built of marble, there are numerous additional versions across the world made of other materials, including bronze.

It shows a warrior in his dying moments, his face distorted in misery as he collapses from a lethal wound to his chest. The sculpture, as a picture of a defeated adversary, depicts heroism in defeat, self-possession in the face of death, and the acknowledgment of nobility in a foreign race.

Apollo Belvedere (140 CE) by Leochares

| Artist Name | Leochares |

| Date Completed | 140 CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 224 |

| Location | Vatican Museums, Vatican City |

The Apollo is currently regarded to be a Hadrianic-era Roman design done in a Hellenistic manner. One reason experts believe it is not a replica of an older Greek statue is the distinctly Roman pseudocrepida footwear. The Greek deity Apollo is represented as a standing archer with an arrow in his hand. While there is no agreement reached on the exact narrative detail presented, the general consensus has been that he has just successfully slain Python, the Chthonic serpent defending Delphi. It might also be the killing of the giant Tityos, who attacked his mother Leto, or the Niobids event.

The massive white marble sculpture stands 2.24 meters tall. Its sophisticated contrapposto, which appears to place the figure both frontally and in profile, has received significant praise.

The arrow has barely left Apollo’s bow, and the strain on his muscles is still palpable. His softly curled hair cascades down his neck in ringlets and rises smoothly to the crown of his head, which is ringed by the strophium, a band emblematic of gods and kings. His quiver hangs over his right shoulder. Except for his robe and sandals fastened at his right shoulder, raised up on his left arm, and flung back, he is naked. When Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli discovered the sculpture, the lower half of the left hand and right arm were gone.

Judith and Holofernes (1460) by Donatello

| Artist Name | Donatello (1386 – 1466) |

| Date Completed | 1460 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 236 |

| Location | Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy |

In the sculpture, a beautiful Jewish widow, Judith, lifts her sword to sever the head of Holofernes, the Assyrian army’s leader. She has already struck him, which is why he appears to be dead. She is gripping Holofernes’ head by his hair. Judith appears to be thinking, probably assessing the possibility of murdering Holofernes in order to defend people from her city and thus breaking one of the Ten Commandments. At the same time, she is presented as a courageous and powerful woman.

Donatello fashioned the gown in a realistic manner. The clothing is crumpled, as one might anticipate in this type of situation, and it hangs elegantly over her lifted arm.

The shattered body of Holofernes is lying at Judith’s feet. He seems to be dead, with his arms dangling strangely and his mouth portrayed wide open. This bronze figure had initially been gilded, and remnants of the gold may still be seen on Judith’s sword. It is also one of the earliest “in the round” monuments, meaning that you can view it from any angle.

The work of art served as a reminder to the people of Florence that no matter how powerful the city’s opponents were, even the most humble members of society could help Florence win. Originally, an inscription relating to the Medici family as the guardians of Florence’s freedom was commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici. It was, however, removed after the Medici’s were expelled from Florence.

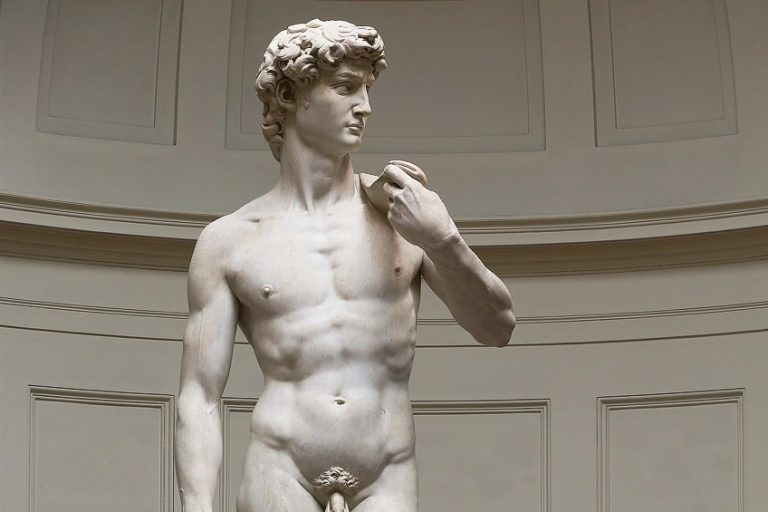

David (1504) by Michelangelo

| Artist Name | Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) |

| Date Completed | 1504 |

| Medium | Marble sculpture |

| Dimensions (cm) | 517 |

| Location | Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy |

Michelangelo’s David, arguably the world’s most well-known sculpture, may be located in Florence. At 517 cm tall and meticulously crafted from marble, this beauty towers over onlookers. The theme of this sculpture is the famous biblical figure of David, who is about to face the almighty giant known as Goliath. This sculpture exemplifies Michelangelo’s artistry and attention to detail as he carved the naked figure, taking special care to perfect the subject’s attitude just before a battle.

While there are other reproductions, many of which can also be found around Italy, the original can still be seen in the Galleria dell’Accademia. Every year, hundreds of tourists visit the city to see the magnificent work of art by one of the Renaissance’s most renowned artists.

This is a traditional underdog story, yet Michelangelo’s version of David is an embodiment of masculine perfection. The Italian statue’s scale is the product of basic logistics: initially planned for installation in a ceiling niche of the Florence Cathedral, the sculpture needed to be large enough to be seen from the seats below. Despite his lack of competence with large-scale sculpture, Agostino di Duccio was initially granted the commission.

Duccio went to the nearby Carrara quarries to choose a marble block, but his lack of knowledge led him astray: he chopped a tall but narrow block full of defects, small holes, and visible veins. The quarry had difficulty preparing and shipping the big stone, and when it arrived in Florence, Duccio saw he had made a mistake and abandoned the project. The block sat for several years before Antonio Rossellino attempted to rescue it. He, too, promptly discarded the marble, and the block remained in the Opera del Duomo’s courtyard for the next 25 years.

Moses (1515) by Michelangelo

| Artist Name | Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) |

| Date Completed | 1515 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 235 |

| Location | Basilica di San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome |

The Moses statue summarizes the entire monument, which was designed but never completed as Julius II’s tomb. It was designed to house one of the six enormous figurines that adorned the tomb. Moses, the elder brother of the Sistine Prophets, is also a symbol of Michelangelo’s own ambitions. It was completed as part of Michelangelo’s second project for Julius II’s tomb. Possibly prompted by the medieval notion of man as a microcosm, he combined the elements in the allegorical form: the figure’s flowing beard represents water, the frantically twirling hair represents fire, and the heavy drape represents earth.

In a sense, Moses represented both the Pope and the artist, as two people who shared a trait known as “terribilità.” The Italian statue was designed for the second floor of the tomb and was intended to be seen from beneath rather than at eye level as it is today.

The Biblical figure, Moses, is portrayed in the same sitting stance as in Michelangelo’s renowned Sistine Chapel fresco. Michelangelo perfectly depicts Moses’ rage at seeing the Israelites worshiping a false god, the Golden Calf. It can seem rather hard to believe that this world-renowned artwork’s delicate, smooth lines, complex detailing, and stern expression are carved from a piece of marble.

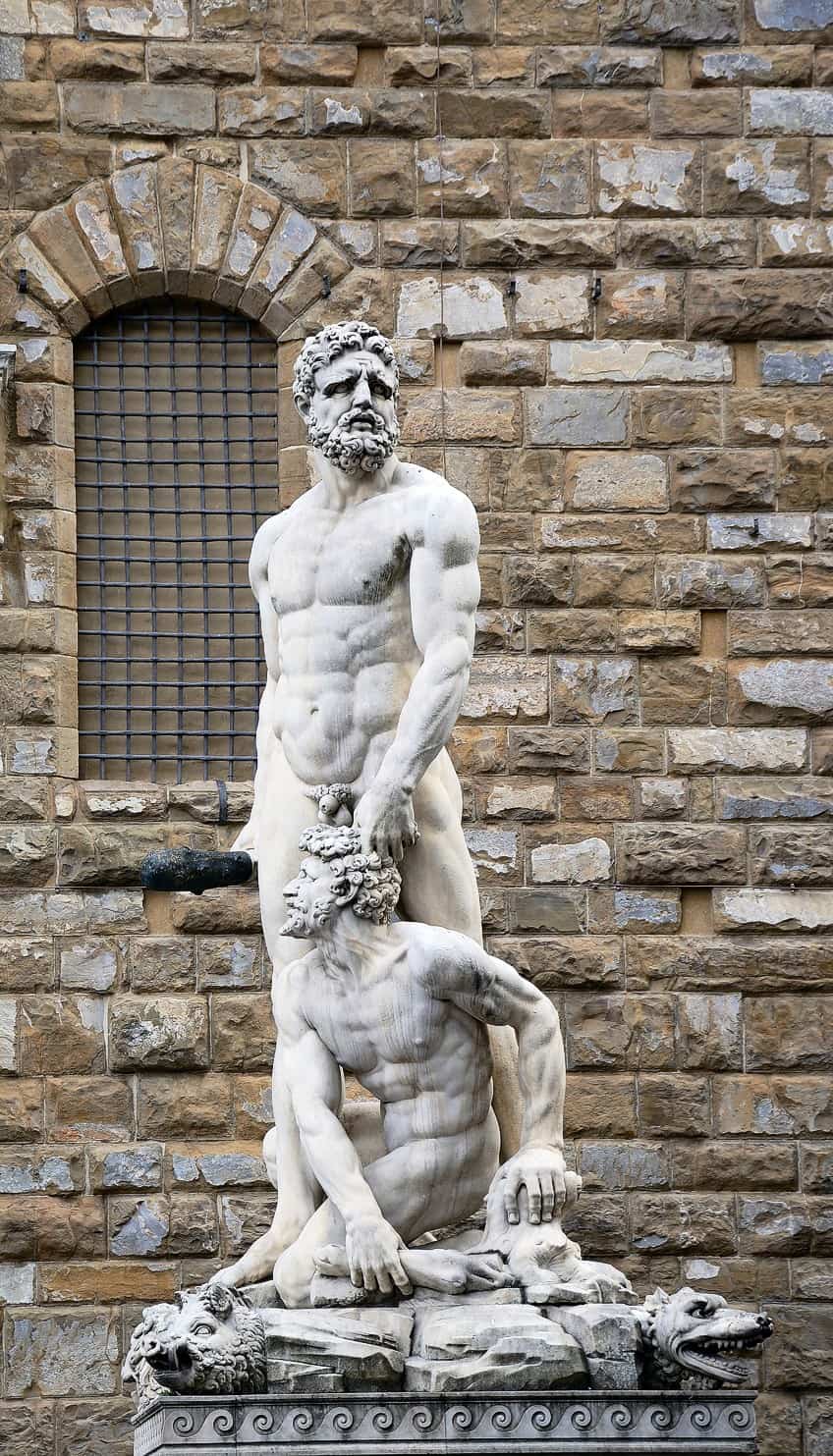

Hercules and Cacus (1534) by Baccio Bandinelli

| Artist Name | Baccio Bandinelli (1493 – 1560) |

| Date Completed | 1534 |

| Medium | Marble/bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 505 |

| Location | Piazza della Signoria, Florence, Italy |

This sculpture, made of white marble, represents Hercules, a demi-god, waiting before slaying the demon Cacus for stealing animals. The person is depicted naked, as is typical of sculptures from this age, with his power emphasized through somewhat exaggerated musculature. It is one of several Italian statues depicting the subject matter of the conqueror and the defeated. This famous Italian sculpture combines media, with the person grasping what was previously a bronze club. However, in 1994, it was determined that it was actually composed of aluminum.

The sculpture continues to intrigue tourists since it was originally thought to be carved by Michelangelo but was handed on to Bandinelli, much to the chagrin of Benvenuto Cellini and Giorgio Vasari.

Here, Hercules, the demi-god who destroyed the fire-belching monster Cacus during his ninth labor for stealing livestock, is the emblem of physical power, which contrasts neatly with David, who is the representation of spiritual strength, both of which the Medici coveted. Although complaints against the marble were made verbally and in writing following its introduction in 1534, most of them were aimed at the Medici family for destabilizing the Republic and were not of an aesthetic nature. Alessandro de’ Medici arrested a few of the people who had authored these hypercritical lines, indicating a political motive.

Rape of Proserpina (1621) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

| Artist Name | Gian Lorenzo Bernini |

| Date Completed | 1621 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 225 |

| Location | Borghese Gallery and Museum, Rome, Italy |

Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini distinguished himself in Baroque Rome with his unique interpretations and exceptional theatrical manner. He began his career at his father Pietro’s studio, and subsequently his pieces were commissioned by the most powerful individuals in the nation, including cardinals and popes. Bernini’s extraordinary talent epitomizes 17th-century art. One of the sculptural projects that distinguished him from his peers and established him as the most prominent Italian sculptor was his production of a series of large-scale marble statues.

“The Rape of Proserpina” was initially commissioned by Cardinal Scipione Borghese for his home in Rome.

Cardinal Scipione handed the Italian statue to Cardinal Ludovisi, who transported it to his own residence when the sculptural work was completed. The sculpture was not restored to Villa Borghese until 1908, at the behest of the Italian government. The Rape of Proserpina sculpture is constructed of Carrara marble, however, it does not appear to be so because of the fine details. The artist was able to authentically reproduce human bodies–he even stated that the marble became like wax in his hands.

Apollo and Daphne (1625) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

| Artist Name | Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598 – 1680) |

| Date Completed | 1625 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 243 |

| Location | Borghese Gallery and Museum, Rome, Italy |

The sculpture was the final of a series of commissions given to Bernini by Cardinal Scipione Borghese at the start of his career. The sculpture of Apollo and Daphne was commissioned after Borghese gave up his patronage of Bernini’s Pluto and Persephone to Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi. The majority of the work was completed between 1622 and 1623, but there was a gap, most likely for work on his David sculpture, which stopped its completion, and the artist did not complete the work until 1625. Furthermore, the monument was not moved to the Villa Borghese until September 1625.

While the sculpture may be viewed from several perspectives, Bernini intended for the audience to take in the emotions of “Apollo and Daphne” simultaneously, letting the observer grasp the tale in a single glance without having to change where they were standing.

Every time you look at the composition, you will see something new. For instance, when you first glance at the sculpture, you will notice Apollo chasing Daphne. However, after a while, you see the amazing metamorphosis of a living creature into a tree. The gorgeous nymph in front of you is still there, but your hands are already turning into branches and leaves. Later on, the legs start to grow into the earth. Bernini expertly depicted the girl’s curls and the body’s transformation into the bark. He also knew how to polish the surface of the marble to highlight the beauty and majesty of his work.

The Veiled Christ (1753) by Giuseppe Sanmartino

| Artist Name | Giuseppe Sanmartino |

| Date Completed | 1753 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 180 |

| Location | Cappella Sansevero, Naples, Italy |

Giuseppe Sanmartino created this iconic Italian statue after being commissioned by Raimondo de Sangro, Prince of Sansevero. The task was previously given to Antonio Corradini, who passed away before starting it. So the task was given to Sanmartino, who completed his masterwork in 1753.

Giuseppe Sanmartino created a sculpture that is a true test of talent by producing the appearance of a translucent veil covering Jesus’ body and revealing all of his physical characteristics.

Raimondo di Sangro was reputed to be something of an alchemist as well as a rather eccentric character and has inspired a number of legends, including one regarding the veil, which, according to some historians, was apparently the result of an experiment performed by the Prince who changed a material veil into marble. The best way to appreciate this famous Italian statue is with a knowledgeable tour guide who can tell you all the tales and interesting information about it as well as the district where it is located and the extremely ancient street called “Spaccanapoli”.

Perseus Triumphant (1801) by Antonio Canova

| Artist Name | Antonio Canova (1757 – 1822) |

| Date Completed | 1801 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 242 |

| Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

This marble Italian statue was influenced by prior Baroque versions. This marble sculpture depicts the Greek demi-god Perseus grasping the stretched head of Medusa. Canova was able to portray both terror and beauty in Medusa’s face while combining features from both themes to bring the tale of this artwork to life. Canova created this sculpture twice, with the first kept in the Vatican Museums and the replica displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

This sculpture was made for Onorato Duveyriez, the statue’s initial owner, and was given to the Cisalpine Republic for the Bonaparte Forum in Milan.

Later, Pope Pius VII Chiaramonti purchased the statue and placed it on the pedestal of the Apollo of the Belvedere, which had been transported to France during the Treaty of Tolentino. Canova was influenced by the weight, dimensions, and emotive character of the Belvedere Apollo statue in this iconic Perseus monument.

That wraps up our list of famous Italian sculptures that have reached worldwide renown through the centuries. These exceptional Italian statues were made by the most skilled Italian sculptors of their era, turning marble into realistic works of art. Thanks to the longevity of the medium used, we can still appreciate these famous Italian sculptures many centuries after they were originally created. Which of these famous Italian statues is your favorite?

Take a look at our Italian sculptures webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Medium Are Famous Italian Sculptures Made From?

When looking for the most beautiful Italian statues, you’ll notice that nearly all of them have one thing in common: they’re constructed out of marble. This is not to imply that other materials do not produce exquisite sculptures (such as the bronze Judith and Holofernes), but only that marble is the most prevalent. Because marble is soft when first mined from the quarries, it may be effortlessly handled. The stone grows denser and harder as it ages. Marble, particularly white marble, is also more shatter-resistant when compared to other materials.

What Are a Few of the Most Famous Italian Sculptures?

David (1504) by Michelangelo is surely among the most famous Italian statues ever made. Michelangelo is also responsible for making many of the other famous pieces, such as Moses. Another very famous piece is Hercules and Cacus (1534) by Baccio Bandinelli. Gian Lorenzo Bernini is another famous Italian sculptor whose works feature in many lists, such as his famous piece, the Rape of Proserpina (1622).

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Famous Italian Sculptures – A Look at the Top 11 Statues.” Art in Context. September 4, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-italian-sculptures/

Meyer, I. (2023, 4 September). Famous Italian Sculptures – A Look at the Top 11 Statues. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-italian-sculptures/

Meyer, Isabella. “Famous Italian Sculptures – A Look at the Top 11 Statues.” Art in Context, September 4, 2023. https://artincontext.org/famous-italian-sculptures/.