“Moses” Michelangelo – Discover the “Moses” Statue by Michelangelo

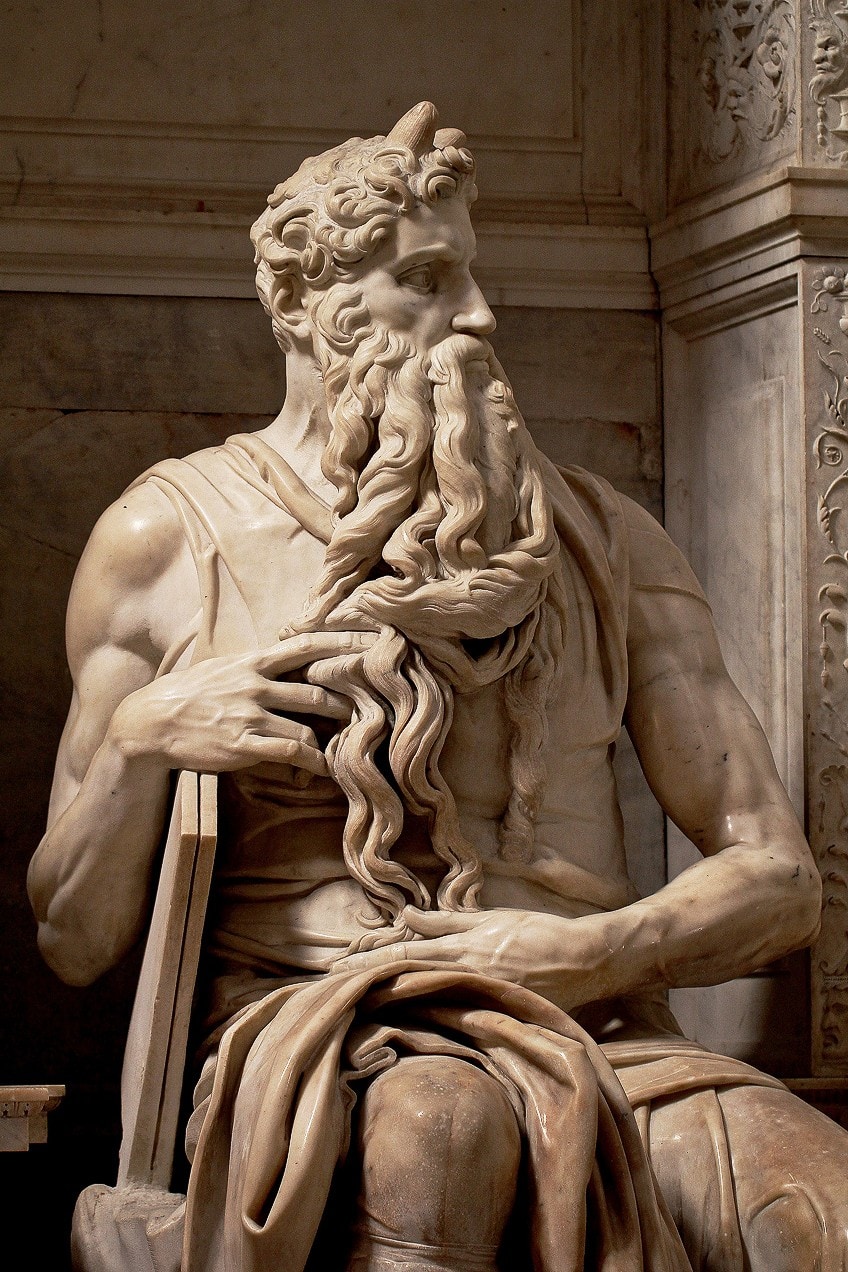

Michelangelo’s statue of Moses was created sometime between 1513 and 1515 and was originally intended to be a component of Pope Julius II’s tomb. The Moses statue is positioned in the stance of a prophet, sitting on a marble chair situated between two adorned marble pillars. Moses by Michelangelo, designed for the second level of the tomb, was intended to be viewed from below rather than at eye level as it is now. It was originally meant to be one of six large sculptures by Michelangelo that were to adorn the tomb.

Moses by Michelangelo

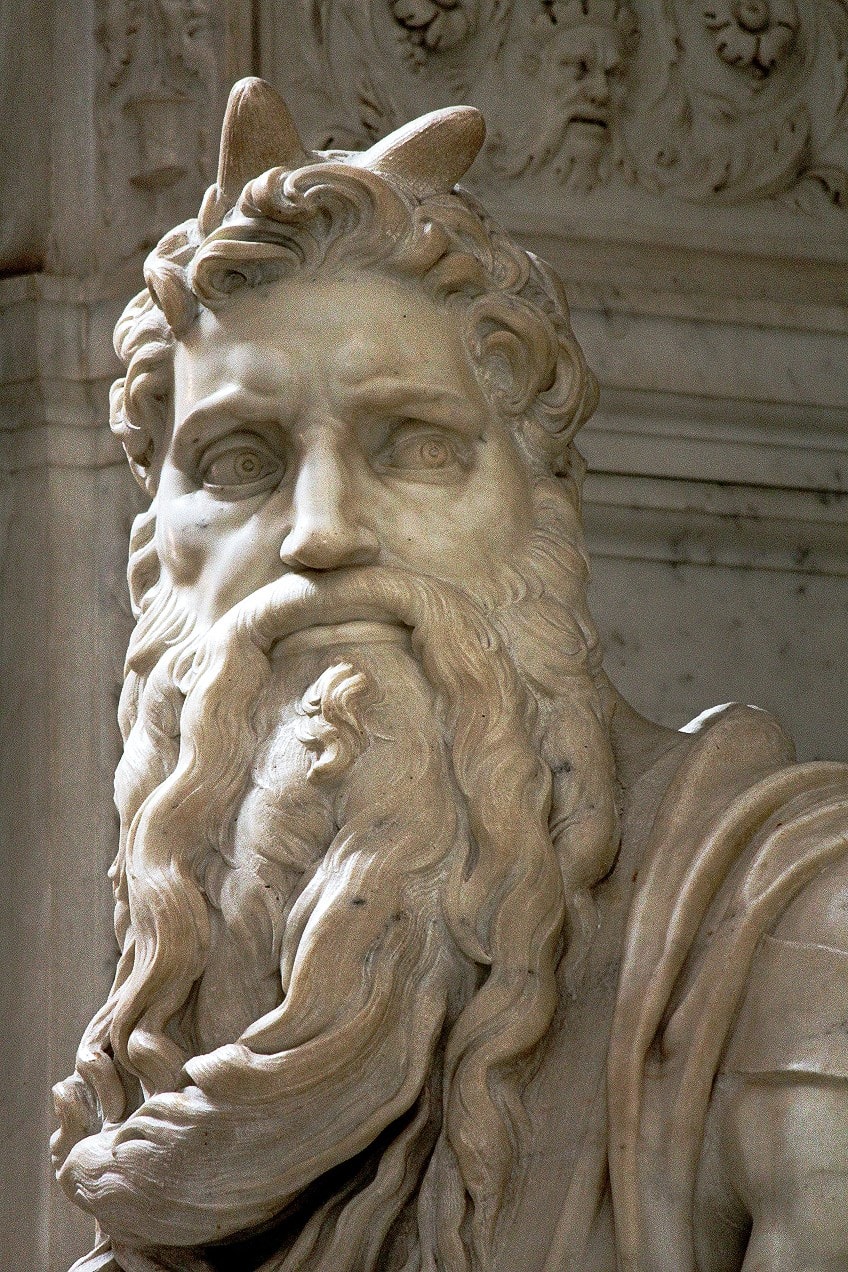

Inspired by a reference in chapter 34 of Exodus, the Moses statue shows the historical person with horns on his head. This is said to be due to St Jerome’s incorrect interpretation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Latin.

Moses is really depicted as having “beams of skin on his face,” which Jerome rendered as “horns” in the Latin version.

The translation error is conceivable because the word “Keren” in Hebrew may mean either “emitted light” or “formed horns.” But before we learn any more facts about the Moses statue, let us take a quick look at the artist behind it.

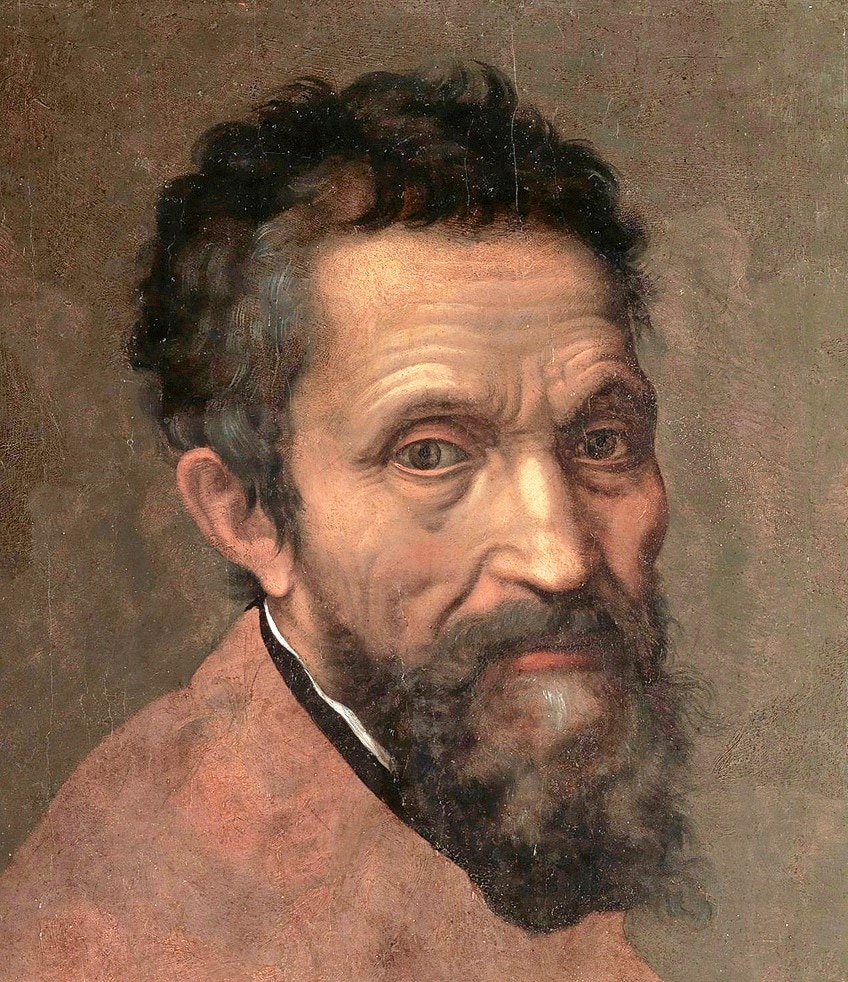

The Artist of the Moses Statue

Contemporaries dubbed Michelangelo Buonarotti “The Divine One” because they thought his creations were unearthly. His paintings were highly sought after and hailed as strong. His followers revered him, artists mimicked him, humanists lauded him, and nine popes patronized him.

Over one hundred portraits of him were done as commemorations throughout the 16th century alone, significantly more than any other creator of the period.

Notwithstanding three biographies produced about Michelangelo during his lifetime, it is via his letters that we learn more about the occasionally generous and frequently humorous perfectionist. Michelangelo not only has the most direct of any historic artist, but he is also among the most written-about painters of all time. He didn’t enjoy debating art, wasting time, or displaying his creation before he was ready.

Despite a few mid-career partnerships, Michelangelo remained cautious and protective, never holding a normal workshop, closing his workshop, and destroying sketches. He also grumbled a lot and could be cocksure, brusque, and rude at times, culminating in a strike to the nose once.

Michelangelo’s Statue of Moses

When Michelangelo completed sculpting David , it was evident that he had produced the most exquisite figure ever – perhaps even surpassing the splendor of the Ancient Greco-Roman artworks. When Pope Julius II heard about David, he invited Michelangelo to travel to Rome and sculpt for him. Michelangelo’s first contract from Pope Julius II was a mausoleum for the pope. This may sound strange to us now, but great kings throughout time have designed magnificent monuments for themselves when they were still living in the expectation that they would be honored forever.

When Michelangelo began work on the Pope’s Tomb, he had big plans.

He envisioned a two-story tower adorned with more than 20 life-sized statues. This was more than a single individual could accomplish in a lifetime. Pope Julius II urged Michelangelo to suspend his progress on the tomb so that he could decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and he was ultimately not ever able to finish his tomb idea.

After running into problems with Julius’ heirs, Michelangelo ultimately produced a greatly reduced version of the monument, which was put in San Pietro in Vincoli (rather than St. Peter’s Basilica, as originally intended).

Description

Vasari once wrote: “Michelangelo completed the Moses in marble, a statue unrivaled by any contemporary or ancient achievement. Seated in a solemn posture, he lays one arm on the slate and the other on his long, lustrous beard, the strands of which are so silky and feathery that it appears as if the metal chisel has turned into a brush. The lovely face, like that of a prophet or a strong prince, seemed to require a veil to cover it, so magnificent and radiant is it, and so beautifully has the artist depicted in marble the purity with which He had bestowed that holy visage.”

The drapes drop in elegant layers, the bones and muscles of the hands and arms are of such perfection, as are the thighs and lower legs, and the feet were decorated with superb footwear, that Moses may now be referred to as God’s companion more than ever because Heavenly Father has allowed his skin to be equipped for the redemption before others by Michelangelo’s hand.

The Michelangelo statue of Moses is shown as sitting; his torso facing forward, his head with its magnificent hair faces to the left, his right foot lies on the earth, and his left leg is lifted so that only the feet touch the earth. The Michelangelo statue of Moses is shown as sitting; his torso facing forward, his head with its magnificent hair faces to the left, his right foot lies on the earth, and his left leg is lifted so that only the feet touch the earth.

His right arm is linked to the Tablets of the Word by something that resembles a textbook in his hand, which he holds with a part of his beard; his left arm is in his lap. His right-hand guards the clay tablets containing the Ten Commandments, but his left hand, arteries pulsating and muscles strained, looks to be backing down from the violent deed. When Moses returned from Mount Sinai, he saw his people worshiping the Golden Calf, the deceptive idol they had created.

His rage transcends the confines of stone, the boundaries of the sculptor’s talent. Few can deny that the person glaring from his marble throne has a genuine mind and true emotions. Nowadays, he glares at the visitors thronging the San Pietro church in Vincoli, Rome. Since the 16th century, Moses’ liveliness has made this piece popular; Rome’s Jewish populace accepted the sculpture as their own. Its power must be related to the rendering of elements that should be unthinkable to express in stone, most notably the beard, which was so clumpy and smoky that its spirals provided wonderful, writhing life.

But, where others may mystify us with methodology, Michelangelo goes beyond, leading us from structured to academic astonishment, trying to make us wonder why Moses gently caresses his beard, why Sculptor has used this hair – in conjunction with the horns that were a traditional characteristic of Moses – to give him a barbarous, demonic appearance.

Interpretations

In his article, Sigmund Freud retells the biblical story’s initial descent down the mountain, bearing the tablets, and discovering the Hebrew people worshiping the Golden Calf, as told in Exodus 32. Moses is described by Freud as being in a complicated psychological state: “We may now, I suppose, allow ourselves to enjoy the benefits of our efforts. We’ve seen how many individuals who have felt the power of this monument have been forced to interpret it like Moses, upset by the sight of his people falling from favor and dancing around an idol.”

This view, however, had to be abandoned since it made them anticipate him to appear at any time, smash the Tables, and complete the job of retribution. Such an interpretation, however, would clash with the plan of making this image, along with three other sitting figures, a part of Julius II’s mausoleum.

They then resumed the rejected interpretation because the Moses they had recreated would not spring up or toss the Tables from him. What was seen in front of them was not the beginning of violent action, but the remnants of one that has already occurred.

Moses wished to act in his first rage, to jump up and seek vengeance, forgetting the Tables; but he has fought the urge, and he would stay sitting and quiet, in his frozen indignation and sorrow tinged with disdain. Freud continued: “He will not discard the Tables so that they would shatter on the stones, for it is for their sake that he has restrained his rage; it is for their sake that he has held his emotions in check. He had to forget the Tables in order to give vent to his fury and anger, and the hand that held them up was removed.”

They started to tumble down and were at risk of breaking. He recalled his objective and abandoned the gratification of his impulses for its sake. His hand reappeared and rescued the unsupported Tables from falling to the earth. In this state, he remained immobile, and it is in this state that Michelangelo depicted him as the keeper of the grave.

As we move our gaze along it, we see three separate emotional layers. The contours of the face represent the dominant sentiments; the midsection of the figure exhibits the traces of restrained movement, and the foot keeps the orientation of the anticipated action. It is as though the directing force came from above and worked its way down.

Freud concluded: “So yet, no comment has been made of the left arm, although it appears to be a participant in our reading. In a gentle motion, the hand is placed in the lap and caresses the tip of the streaming beard. It seemed to be intended to neutralize the ferocity with which the other hand had previously abused the beard.” Another point of view, presented by MacMillan and Swales in their piece, links the artwork to the second set of Tables and the events that occurred in Exodus 34.

They notice that Moses is bringing empty tablets, which the Heavenly Father had instructed Moses to make as preparation for the second offering of the Rule; they also notice that Moses is depicted with “horns,” which the holy scriptures categorize Moses as having only after he came back to the people shortly after the second offering of the Rule. They claim that the monument symbolizes Moses’ encounter with God, as stated in Exodus 33: “The occurrence at issue is the most important portion of the Old Testament tale of the Exodus.”

With doubts about his own and his tribe’s position, he takes the significant risk of asking that they be pardoned, that he be afforded the Lord’s mercy, and that the Lord retake his post and guide them to Paradise. Emboldened by his accomplishment, he next gambles all by requesting that the Lord display his splendor.

It takes no imagination to imagine the profound passion with which such a Moses would have anticipated the Lord: Will he show up? Will he renegotiate the Covenant? “Will he show his radiance?” They further contend that both Paul and Moses had direct encounters with God, a notion and pairing that was essential to the Neo-Platonists, a group to whom the writers compare Michelangelo and Pope Julius II.

According to the writers, the primary expression on Moses’ face is “amazement at coming face to face with the maker.”

Michelangelo’s Moses’ Horns

Michelangelo’s statue of Moses bears two horns on its head, which is a frequent iconographic practice in Latin Christianity. The portrayal of a horned Moses is based on the depiction of Moses’ visage as “horned” in the Latin Vulgate interpretation of Exodus chapter 34, as Moses travels to the congregation after hearing the laws for the second time: “And as Moses descended from Mount Sinai, he clutched the two stones of the truth, and he had no idea that his face was horned from the Lord’s speech.”

This was Jerome’s attempt to accurately translate the difficult Hebrew text. The phrase is currently used to refer to “shining” or “releasing rays.” Even though some scholars claim Jerome committed an actual blunder, based on another commentary he produced, including the one on Ezekiel, Jerome appears to have interpreted it as a euphemism for “glorified,” writing that Moses’ visage had “became ‘glorified,’ or as it reads in Hebrew, ‘horned.” The line was transcribed as “Moses understood not that the look of the flesh of his face was exalted” in the Greek Septuagint, which Jerome also had available.

Generally, medieval theologians and academics took Jerome’s usage of the Latin term for “horned” to signify praise of Moses’ face. The belief that the ancient Hebrew was complex and unlikely to imply “horns” remained throughout the Renaissance.

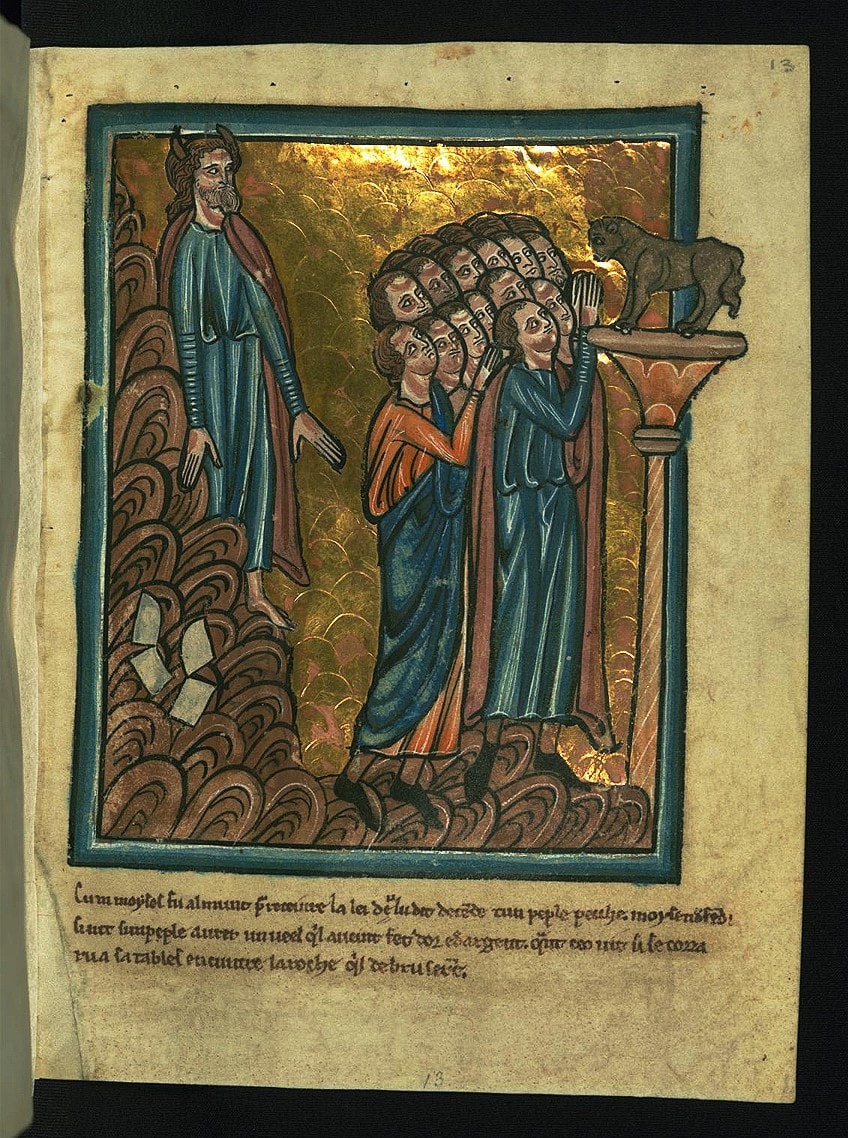

While Jerome finished the Vulgate in the late fourth century, the first recorded adaptations of the Vulgate’s precise vocabulary in the arts may be discovered in an English pictorial book written in commonplace language around 1050.

For the following 150 years or more, there is little evidence for other representations of a horned Moses. Following that, such pictures multiplied and may be found, for instance, in the Sainte-Chapelle, Chartres Cathedral, and Notre Dame Cathedral, even though Moses was frequently shown without horns. The popularity of images of a horned Moses declined dramatically in the 16th century.

In Middle Ages Christian art, Moses is shown both with and without horns; often in splendor, as a prophet and forerunner of Jesus, but often in negative circumstances, particularly with Pauline contradictions between religion and rule – the imagery was not black and white. The use of horns initially appears in 11th-century England. Minkoff hypothesized that, while the horns of Moses were never connected with those of the Devil, they may have acquired a negative meaning with the rise of anti-Jewish feelings in the early modern period.

A book released in 2008 pushed the argument that the “horns” on the sculpture were never supposed to be visible and that interpreting them as horns is incorrect.

“It was never endowed with horns. Moses was intended by the artist to be a work of art not just in sculpting but also in special visual effects befitting any Hollywood film. As a result, the artwork had to be raised and oriented straight ahead, toward the basilica’s front door. The two bulges on the skull would have been undetectable to a spectator gazing up from the floor below, with just the light reflected off of them visible.”

This perspective has been called into question. Ever since the 19th century, there has been a succession of critical remarks on the sculpture that have defined its aspects (which, by the way, have previously been understood in two quite different approaches by his two biographers) in light of the most diverse and not always valid conclusions.

With regard to Savonarolian thinking, it was seen as a metaphor for the pope, a reflection of Michelangelo, and a cosmic creature composed of the four elements. His scowl and wary look have been rationalized as his response to watching Jewish people making sacrifices to the bronze snake.

A 19th-century psychological explanation of his mien prepared the path for Sigmund Freud, who evaluated the artist’s rendition of the scriptural protagonist in relation to an outstanding and sensible strength of self over desire, noting it as the impression of a spiritual hero willing to sacrifice his personal emotive life to protect the outcome of the Jewish people.

It is simple to discern the contrast between the early and high Renaissance ideals when trying to compare Michelangelo’s Moses to a sculpture by Donatello. The comfortable figure of St John by Donatello lacks the force and energy of Michelangelo’s sculpting. As one can observe, this may be a fairly dull job.

Even in a seated position, Michelangelo has given a complete figure dynamism and motion. We have a distinct feeling about the messenger and his obligation to follow God’s will in Michelangelo’s dramatic figure of Moses. Moses is alive, breathing, a present-day character who reflects God’s will and strength, not an inert character from the ancient biblical past.

In this article we covered all the facts about Moses, detailing Michelangelo’s Moses’ horns, and many other interesting facts about the Moses statue. The huge figure sculpted in 1513 to decorate the tomb commissioned by Julius II to Michelangelo was not finished until after the death of the pope, who is preserved in St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. The painting, influenced by Donatello and Raphael, portrays a magnificent Moses seated with the Plates of the Commandments under one arm, while his other hand gently caresses his long beard, which Vasari describes as a “stroke of the brush rather than a chisel.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Does Moses Have Horns?

The Moses statue, which was inspired by a passage in the Holy scriptures of Exodus chapter 34, depicts the historical figure with horns on his head. This is attributed to St. Jerome’s erroneous translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Latin. Moses really has beams of skin on his face, which Jerome translated as horns in the Latin version. The translation mistake is understandable since the Hebrew word Keren can mean either emitted light or formed horns.

Why Was the Moses Statue Created?

Michelangelo’s Moses statue was produced between 1513 and 1515 and was supposed to be part of Pope Julius II’s tomb. The Moses statue is seated on a marble chair between two decorated marble pillars, in the posture of a prophet. Moses, conceived by Michelangelo for the tomb’s second level, was supposed to be viewed from below rather than at eye level as it is now. It was initially conceived as one of six enormous sculptures by Michelangelo to embellish the grave. The work, meant for St. Peter’s Basilica, was relocated to San Pietro in Vincoli due to conflicts between the Pope and Michelangelo. Julius II, in reality, was entirely engrossed by the basilica’s rebuilding and had laid aside the concept of a tomb.

Who Was Moses?

The most significant Jewish prophet is Moses. He is widely regarded as the author of the Torah and the leader of the Israelites when they fled Egypt and crossed the Red Sea. In the book of Exodus, he is born during a period when Egypt’s Pharaoh had ordered that every male Hebrew be killed.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, ““Moses” Michelangelo – Discover the “Moses” Statue by Michelangelo.” Art in Context. April 22, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/moses-michelangelo/

Meyer, I. (2022, 22 April). “Moses” Michelangelo – Discover the “Moses” Statue by Michelangelo. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/moses-michelangelo/

Meyer, Isabella. ““Moses” Michelangelo – Discover the “Moses” Statue by Michelangelo.” Art in Context, April 22, 2022. https://artincontext.org/moses-michelangelo/.