Famous Expressionism Paintings – 10 Iconic Artworks

Famous Expressionism artworks are venerated in art history and credited to the mysterious individuals that arose from the Expressionism art movement at the beginning of the 20th century. Expressionist paintings are intense, intimate, and portray the fascinating depictions of expressionist artists’ inner worlds. Expressionist art is characterized by sweeping brush strokes, vibrant color palettes, and abstracted forms that depict emotional observations about the world, as well as collective feelings shared during moments of turmoil and conflict. In this article, we will introduce you to the best Expressionist artworks in art history that have shaped the movement and raised the value of emotional expression in art. Keep reading for more about this incredible movement!

An Introduction to Famous Expressionism Artworks

Shifts in creative techniques and approaches erupted across Europe in the beginning of the 20th century as a reaction to major societal developments. New technology and vast modernization efforts changed people’s perspectives of the modern world and artists represented the cognitive effect of these changes by shifting away from a literal depiction of what they observed to a more psychological and emotional interpretation of how the environment impacted them. It was through Expressionism that artists began to explore and prioritize emotions and feelings as a key component of creating impactful artwork, while challenging existing conventions for what art could be.

The term “Expressionism” was created by Antonin Matejcek, an art historian, who used the term to describe the complete reversal of Impressionism.

Although the Impressionists produced works that expressed the grandeur of creation and the physical body, the Expressionist artists produced paintings, as per Matejcek’s words, to convey the landscapes of their emotional life via the depiction of brutal and harsh themes. It should be emphasized, though, that neither the members of Die Brücke, nor other sub-movements such as Der Blaue Reiter in Munich, ever identified as creators of Expressionist paintings, and that the term was extensively used in the initial part of the 20th century to describe a range of genres, including post-Impressionism.

Exploring the 10 Most Famous Expressionism Paintings

Expressionism art may be extremely broad to understand and challenging to define, but by studying its different styles and evolution, you can easily identify its key elements. Expressionist art encompasses several nations, techniques, ideologies, and time periods. Expressionism artworks were characterized by their use as a method of communication and sociological reflection rather than being understood as a system of stylistic ideals. Below, we will dive into the top 10 most famous Expressionism paintings that exemplify the expressive and lively character of the period. From German Expressionist painters such as Franz Marc to provocative artists like Egon Schiele, you can be sure to enjoy this selection of the top 10 most famous Expressionism artworks!

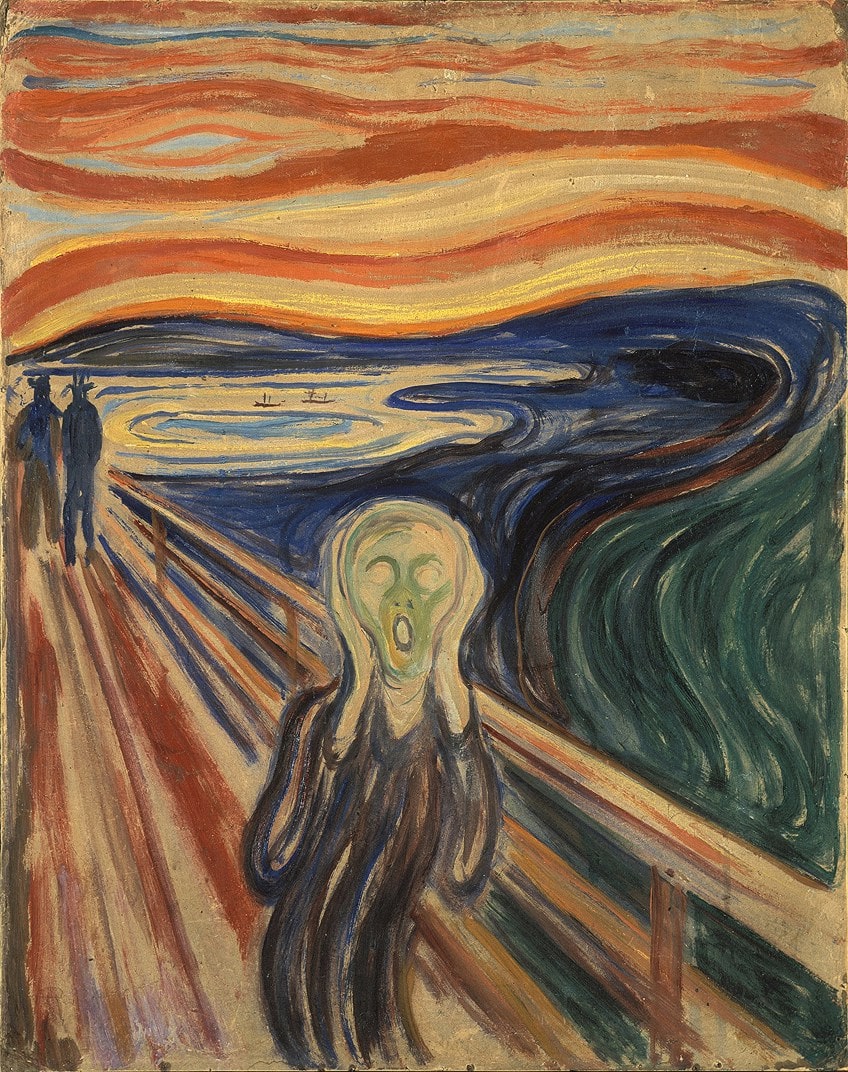

The Scream (1893) by Edvard Munch

| Artist Name | Edvard Munch (1863 – 1944) |

| Date | 1893 |

| Medium | Tempera and crayon on cardboard |

| Dimensions (cm) | 91 x 73 |

| Where It Is Housed | National Museum, Oslo, Norway |

The Scream is essentially a personal artwork based on Munch’s real-life experience of hearing a piercing scream cutting through the environment, while on a stroll after his two friends, shown in the distance, had left him. Edvard Munch was one of the greatest early Expressionist artists of the late-19th century, who created The Scream twice.

In the painting, Munch represented the noise in a way that, when taken to excess, may shatter personal character. This reflected the reality of the noise, which must have reverberated through his psyche at a moment when he was in an unstable state.

The sweeping curves symbolize a subjective logical fusion forced on nature, in which a variety of specifics is merged into a whole of organic inspiration with feminine undertones. However, mankind is a component of the natural world, and its incorporation into such a wholeness annihilates any form of individuality within the composition.

It was around the early 20th century when Munch began to include these themes into several of his paintings, albeit only in restricted or modified forms. However, in showing his own horrific experiences, he relinquished the notion of form and represented a distorted figure, whose reaction flows with the scene around him. The Scream may be understood as reflecting the misery of this unifying factor, thus obliterating human identity.

Despite the fact that the protagonist was based on Munch, he shows no similarity to him or anybody else.

Several factors demonstrate that Munch was well aware of the dangers of such work for “disturbed artists” like himself. He quickly discarded the approach and seldom, if ever, exposed a front figure to such extreme and methodical deformation again.

Hans Tietze and Erica Tietze-Conrat (1909) by Oskar Kokoschka

| Artist Name | Oskar Kokoschka (1886 – 1980) |

| Date | 1909 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 76 x 136 |

| Where It Is Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Hans and Erica Tietze, Viennese art scholars, commissioned the 23-year-old Kokoschka to create a marital picture for their mantle in 1909. Mrs. Tietze noted that she and her spouse were portrayed separately, as shown by their distinct attitudes and glances. Kokoschka employed thin layers of color to generate the foggy environment enveloping the lovers and scratched the color with his fingertips to convey a sensation of sizzling excitement. The Tietze’s, who were well known art historians, sold this painting to the Museum of Modern Art in 1939, barely one year after the pair moved to New York.

Kokoschka’s focus on their anxious and delicate hands hinted at the pair’s characters, which the painter defined as “enclosed personas, so fraught with tensions”.

The Tietze’s may have been social and prominent art historians in their day but Kokoschka bypassed their public personalities to discover a subtle sensitivity in their private connection. Erica stares out at the viewer while Hans glances at her hand and gestures towards it without reaching it, forming a curve with his hands, as well as her arm, which appears interrupted at its apex by a thin space representing a metaphysical discharge of energy. The duo emerges from a glistening foundation of russets and dark blues, where their contours appear to blend in spots. Scuffs in the thinner oil spots, produced with the artist’s fingernails, created a pattern of ethereal half-marks surrounding the characters, which remind one of a faint aura of glistening intensity.

Kokoschka, along with his Viennese colleague Egon Schiele, attempted to exceed scholastic conventions with the art of physical and emotional immediacy, and “depict the image of humans living”.

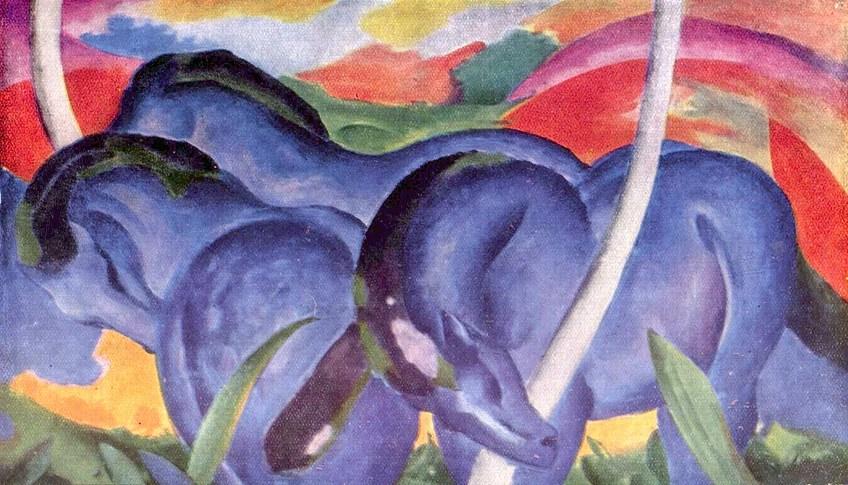

Large Blue Horses (1911) by Franz Marc

| Artist Name | Franz Marc (1880 – 1916) |

| Date | 1911 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 104 x 181 |

| Where It Is Housed | Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States |

This Expressionist artwork, which depicts three bright blue steeds staring down before a scene of undulating red-colored hills, is distinguished by its use of primary colors, clarity, and powerful emotions. The horses’ simple and curved shapes are repeated in the patterns of the surrounding terrain, merging the creatures and forming a forceful and appealing dynamic composition. The curving lines used to illustrate the topic were intended to express “a sensation of harmony, tranquility, and symmetry” in a spiritually pristine wildlife setting, which through observation, allows humans to engage in this harmonious relationship. This famous Expressionism painting was created by Franz Marc in 1911, who viewed the color blue as sacred.

Marc assigned the colors he employed in his art a psychological or emotional significance, with blue symbolizing the masculine identity and divinity, yellow symbolizing feminine delight, and red symbolizing brutality.

Marc utilized blue to symbolize mysticism throughout his profession and his choice of the brilliant hue is regarded to have been an effort to reject the physical world and conjure a metaphysical or transcendent core. This was one of the artist’s first large works representing animals and it was the most notable of his collection in equestrian portraiture. Jean Bloé Niestlé, a Swiss painter, pushed Marc to “encapsulate the soul of the creature”.

The sensation created by the subject, according to Franz Marc, was more significant than depicting zoological correctness.

Houses at Night (1912) by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

| Artist Name | Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884 – 1976) |

| Date | 1912 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 95 x 87 |

| Where It Is Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff came to Berlin after he co-founded the Dresden-based group, Die Brücke, where he created this abstract painting of a row of houses. The structures wobble apart at weird angles over a hauntingly deserted street and symbolize modern metropolitan society’s isolation. Despite the fact that Schmidt-Rottluff created Houses at Night, the impact of woodblock print styles is obvious; the abstract and minimalistic forms have a sharp and visual aspect comparable to Schmidt-Rottluff’s many print pieces.

The brilliant colors complement the crude contours of the canvas, suffusing the image with an underlying feeling of discomfort and strangeness.

The constant unease was the core of contemporary, metropolitan life. For Expressionist artists, the pervading unease constituted the core of the modern metropolitan universe. The creator’s avant-garde viewpoint of the street scene was highlighted by the use of sharp shapes and brilliant acidified color schemes. The protruding angular patterns in this composition are reminiscent of the perplexing set designs for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, a renowned Expressionist film created eight years later.

Robert Wiene, the film’s director, used the warped viewpoint of Expressionist art to portray the fear of a village tormented by a killer.

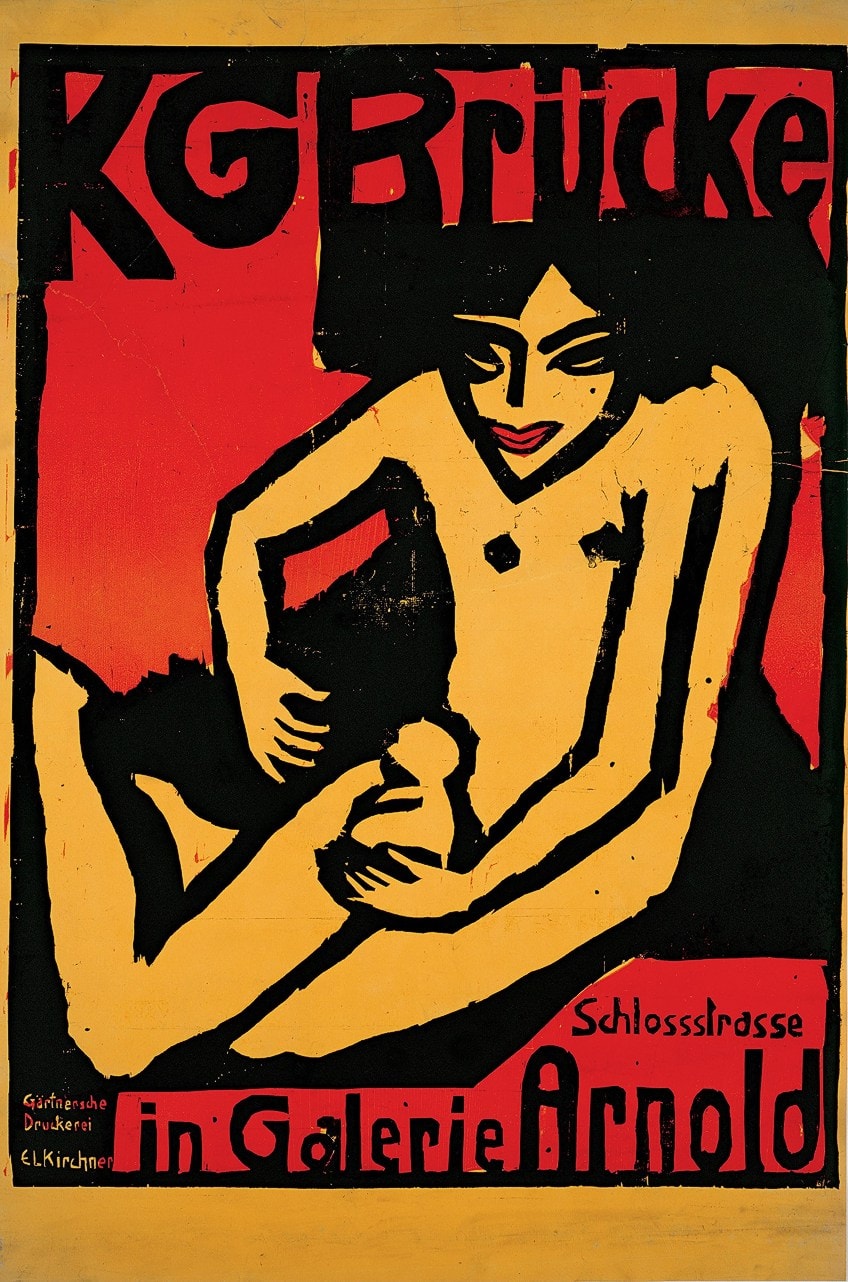

Street, Berlin (1913) by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

| Artist Name | Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880 – 1938) |

| Date | 1913 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 121 x 91 |

| Where It Is Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner displays a bustling city scene with many people walking down the road. Kirchner depicts two ladies in the front with their forms occupying a substantial section of the composition, making them the painting’s central focus. The lady on the left is dressed in a violet gown, which stands in contrast to the largely black attire of the males who surround the women. The males in the backdrop lack distinguishing characteristics and appear to be carbon copies of one another.

Their clothing blends into one another, and their non-distinctive facial characteristics draw the viewer in since they are the only two figures with a sense of individuality.

Kirchner used a selection of non-naturalistic colors in the painting, such as the flesh of the characters, which changes between orange and pink hues, as well as the blue hues in the surroundings. The non-naturalistic qualities are prevalent in German Expressionism and Kirchner’s other works from this time. Kirchner’s brushstrokes are also free and transparent.

The brush strokes evoke a feeling of movement, which builds on the busy quality of the streetscape. The perspective’s downward tilt and the contrasting diagonal lines in the brushstrokes produce a deformation and a sensation of movement. The observer is accosted by the individuals on the road, as if they are going to flow out of the painting and into your environment. This artistic decision also brings one closer to the women, while distancing the viewer away from the faceless masculine characters.

Expressionist principles in German painting have been traced all the way back to Grünewald and Kandinsky, with Kirchner expanding on the notion of dramatic brushstrokes and motion in his own works.

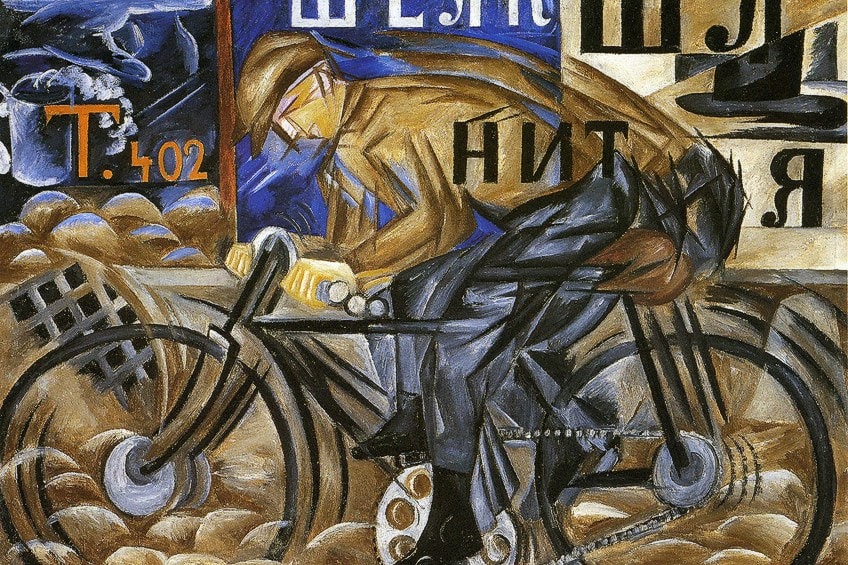

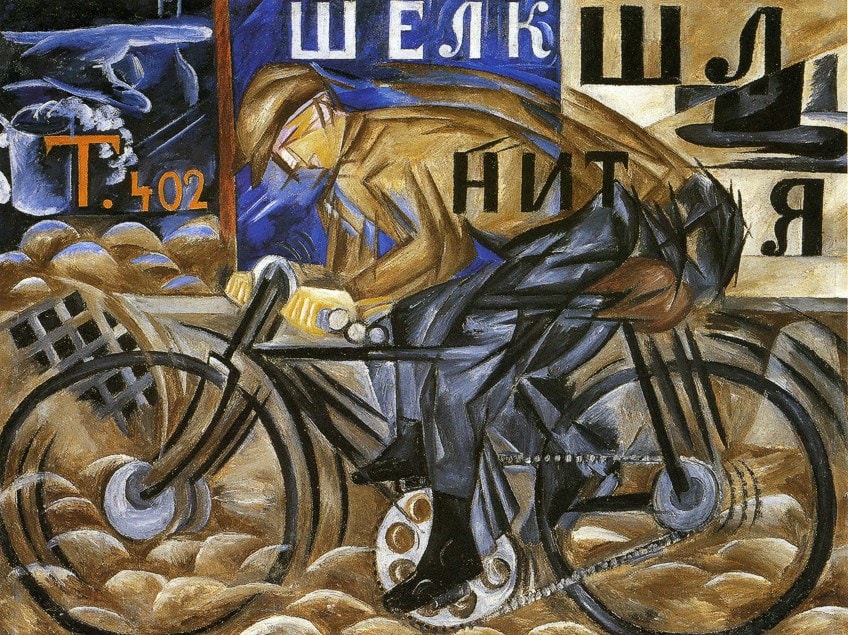

The Cyclist (1913) by Natalia Goncharova

| Artist Name | Natalia Goncharova (1881 – 1962) |

| Date | 1913 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 78 x 105 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia |

In this famous Expressionism painting by Natalia Goncharova, a bike sprints through a cobbled road in front of a contemporary commercial highway with giant advertising billboards and road signs. The cyclist accelerates forward while his pointed workers’ cap transforms his forehead into a circular shape that mimic the street’s cobblestones. His cap contrasts with the shiny black bowler hat, which was a sign of fashionable aristocracy, while the lettering in the end section of the composition plays on language.

The top hat mirrors the curvatures of the cobblestones on the ground and serves as one of the letters of the word “hat” in Russian.

The painter duplicated the cyclist’s legs, feet, and torso, as well as the chassis and tires of the bicycle to represent not only forward velocity, but the up-down oscillations of the tires hitting the cobblestone streets. The Russian symbols that spell “silk,” “hat,” and “thread” allude to the creator’s conceptual design and expertise in fabrics.

Furthermore, the visible and solitary “Я “, which is “I” in Russian, represents Goncharova’s signature.

Sitting Woman with Legs Drawn Up (1917) by Egon Schiele

| Artist Name | Egon Schiele (1890 – 1918) |

| Date | 1913 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 121 x 91 |

| Where It Is Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

The use of orange and green hues in this famous Expressionist painting by Egon Schiele creates an eye-catching juxtaposition, giving this artwork a considerable punch. The backdrop for this image is quite calm and intimate to the artist, giving us a glimpse into his private affairs. Edith, his wife, sits on the ground, lazily relaxing. During this period, Schiele created a number of portraits of his wife depicted in comfortable positions.

In his lifetime, Schiele created a plethora of sensual art but in this case, he opted to fully clothe his spouse.

This is most likely due to frequent interference with his works since he was also jailed multiple times for creating “lewd” paintings. It is terrible that any painter would be hampered in this manner but Schiele did not improve his situation by associating himself with women who were still in their teenage years, which only fueled rumors about his personal life and character.

Schiele was a superb sketcher who would first lay out the shapes of his portrait models before adding color to finish the composition. In this example, he opted for a varied palette and included a black hue as well as blues, greens, and oranges. His wife is sitting on the ground with her head rested on one knee and she is looking at Schiele with a fearless stare. Schiele preferred to bend his figures in all sorts of unusual positions and he seldom opted for standard portraiture techniques.

This was one instance of how Schiele’s work depicted modern culture and went on to inspire many others in the first half of the 20th century.

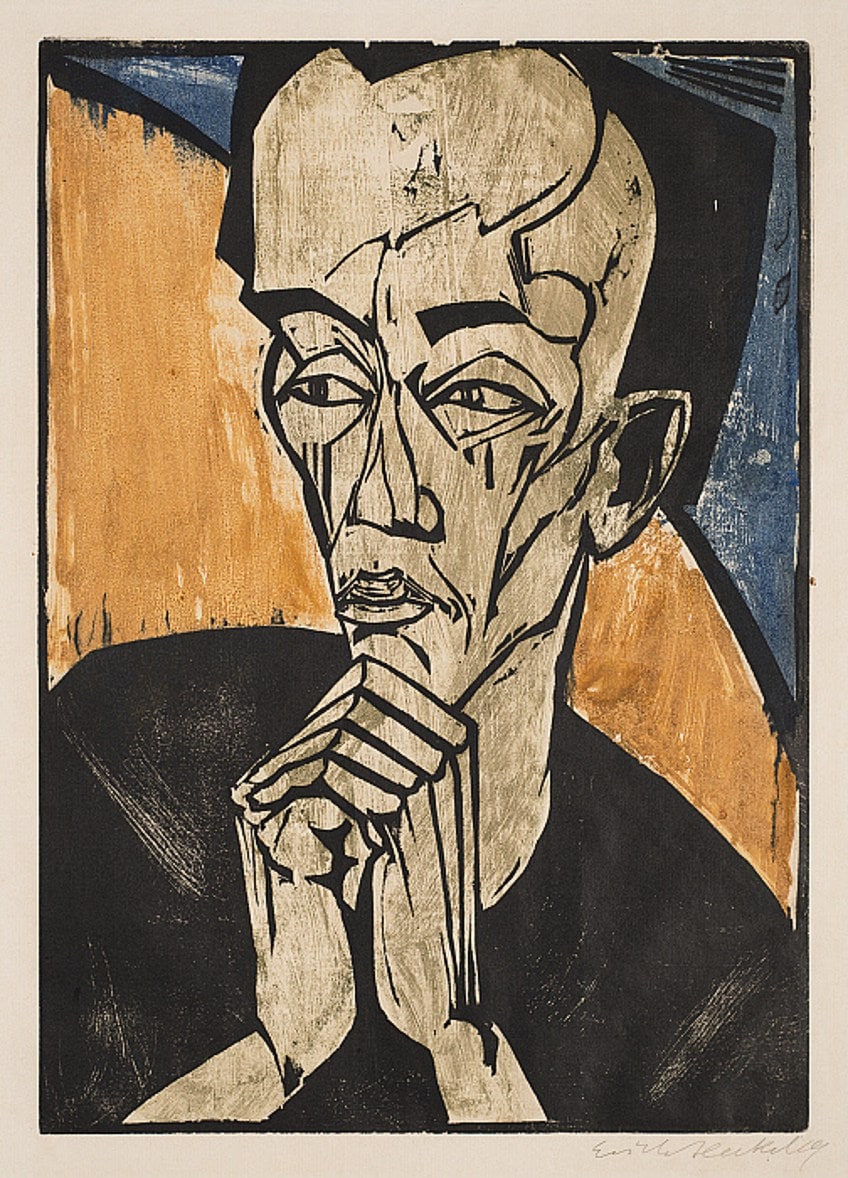

Portrait of a Man (c. 1918) by Erich Heckel

| Artist Name | Erich Heckel (1883 – 1970) |

| Date | c. 1918 |

| Medium | Woodcut |

| Dimensions (cm) | 32 x 46 |

| Where It Is Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Erich Heckel was a founder of the artistic movement known as Die Brücke, which began in Dresden in 1905. Painters of Die Brücke opposed the dominant conventional style in lieu of a new aesthetic statement that would serve as a bridge between the old and the new art styles. Woodblock printing has a rich tradition in Germany, dating back to the 15th century. Heckel and his collaborators at Die Brücke resurrected the method by creating a massive quantity of woodcut images.

Heckel worked extensively with woodblock printing and was drawn to the method for its pure emotionalism and austere appearance, as well as its historic German pedigree.

While many of Heckel’s works portray nudism and city vistas, this sad self-portrait from 1919 takes on a more introspective theme. The model’s haggard face, deformed jaw, and tired eyes, which appear to wander off into the horizon emphasize the person’s mental, emotional, and physical exhaustion. Instead of creating a realistic self-portrait, Heckel expressed the overall attitude of his period, as well as the societal fatigue of his day, both of which were prevalent subjects in many famous Expressionism paintings.

Erich Heckel instantiates his own tortured visage with the tragedies of the war period and the uncertainty of the post-war era.

Mad Woman (1920) by Chaïm Soutine

| Artist Name | Chaïm Soutine (1893 – 1943) |

| Date | 1920 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 96 x 60 |

| Where It Is Housed | National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo, Japan |

Regardless of the idea that Chaïm Soutine’s figure compositions, like his portrayals of other topics, were marked by aggressive brushstrokes and harsh color contrasts, they were extraordinarily adept in their portrayal of the characters’ individuality. His portraits included a frail adolescent, the sun-burned visage of a farmer’s wife, a haughty lady of the aristocracy, and a terrified maid. The wide-eyed look, pinched face, awkwardly clenched arms and shoulders, and unkempt hairstyle in Mad Woman all contribute to the piece’s strange atmosphere.

The woman’s crimson dress and the coarse brushstrokes heighten the painting’s surreal and distorted effect, which leaves the viewer with a haunted sensation.

In comparison to Chagall, who had also been nurtured in a Jewish neighborhood and displayed yearning for his homeland, Soutine was always angry in his representation of the planet’s bursting cruelty, due to his persecuted mentality formed of his childhood experience with impoverishment and tyranny. His figure compositions foreshadow Francis Bacon’s works, who represented “humanity in the misery of one’s own conditions”.

Soutine distorted elements and figures until they became the topics themselves. This methid later inspired figures such as Jean Fautrier, the famous Informalist artist.

Harold Rosenberg (1956) by Elaine de Kooning

| Artist Name | Elaine Marie Catherine de Kooning (1918 – 1989) |

| Date | 1956 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 203 x 149 |

| Where It Is Housed | National Portrait Gallery, London, United Kingdom |

Harold Rosenberg (1906–1978) was a famous art reviewer and poet, who was best known for his dissertation The American Action Painters (1952), in which he advocated for abstract art, especially that of the works of Willem de Kooning.

He agreed with the artist’s palette “instead of a place in which to replicate, re-design, evaluate, or ‘communicate’ a real or perceived item. What was to be painted on the painting was not a depiction but rather an experience”.

Rosenberg and his wife, Mary Tabak, had been friends with the De Koonings since the 1940s and Elaine had depicted and illustrated him several times. This was the largest and most complicated artwork, representing the reviewer sprawled out in her workshop, while covering the painting with a drink in one hand and a cigar in the other. Elaine created a balance between human resemblance and pure abstraction by combining flowing sketch marks with dark colors and boldly brushed sections of brilliant pigments.

While there were many prolific Expressionist artists in the 20th century, one can also explore the works of precursors such as Vincent van Gogh and later Expressionists such as Emil Nolde, George Grosz, Max Beckmann, August Macke, and Otto Dix, who paved the path forward for the development of other movements such as New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) and Neo-Expressionism.

Famous Expressionism paintings appeared in numerous towns across Germany at the same time as a demonstration of the broad angst over humanity’s progressively dissonant connection with the earth. The emergence of Expressionism artworks saw the establishment of new norms in the production and evaluation of art. Expressionist art intended to emerge from the emotions of the creator instead of a visual description of the environment. At the same time, the criteria for judging the value of an artwork shifted toward evaluating the nature of the creator’s emotions rather than an examination of the arrangement.

Take a look at our Expressionist paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Invented the Term Expressionism?

Antonin Matejcek was credited with establishing the term Expressionism. Matejcek was an art historian who established the term to describe the polar opposite styles of Impressionism. Although the Impressionists created work to represent the grandeur of creation and the physical body, the Expressionists, according to Matejcek, utilized paint to convey only their inner lives, usually through the depiction of violence and harsh subjects.

What Is Unique About Famous Expressionism Art?

Unlike Impressionism’s bucolic settings and Neoclassicism’s scholarly sketches, Die Brücke painters of Expressionism employed deformed shapes and discordant, artificial colors to provoke an emotional reaction. A minimalist and primal aesthetic also bound the group together. It was a rebirth of ancient mediums and Medieval European art with visual methods such as woodblock printing employed to produce rough and jagged shapes.

What Is Der Blaue Reiter?

The famous Expressionism group Der Blaue Reiter, also recognized as the Blue Rider, was formed by Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky around 1911. This group demonstrated a preference for abstractions, figurative substance, and spiritual connotations in Expressionism. They attempted to portray mental aspects of existence through symbolic and vibrantly colored depictions. The name of the group was inspired by a depiction of a steed and rider from one of Wassily Kandinsky’s works.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Famous Expressionism Paintings – 10 Iconic Artworks.” Art in Context. November 10, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-expressionism-paintings/

Meyer, I. (2021, 10 November). Famous Expressionism Paintings – 10 Iconic Artworks. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-expressionism-paintings/

Meyer, Isabella. “Famous Expressionism Paintings – 10 Iconic Artworks.” Art in Context, November 10, 2021. https://artincontext.org/famous-expressionism-paintings/.