Eva Hesse – The Sculptor Who Brought Life to Minimalism

Eva Hesse was a German-born sculptor who, in her too-short life, made such remarkable works that it ushered in a whole new movement called postminimalism. Her intimate touch to minimalist art is also seen as the first truly feminist art. This article explores the remarkable life and work of the artist gone too soon.

Artist In Context: Eva Hesse’s Biography

Eva Hesse didn’t receive the acclaim that she deserved until later in her short career. Although her early works went largely unnoticed in the art world, her tenacity and drive finally paid off and she became a shining star in the 1960’s thriving art scene. Eva Hesse’s biography shows a journey of a young artist who fought through years of anxiety and doubts to finally emerge as a confident and truly unique master and pioneer. This article will explore the short but powerfully transformative career of Eva Hesse the artist.

| Date of Birth | 11 January 1936 |

| Date of Death | 29 May 1970 |

| Country of Birth | Hamburg, Germany |

| Art Movements | Surrealism, Minimalism, Postminimalism, Feminist Art |

| Mediums Used | Painting, Sculpture |

The Dark Years: Birth and Early Life

Eva Hesse was born in 1936 in Germany to a family of observant Jews. This was an extremely dangerous time for her family to be in Germany as the early segregation and persecution of Jews had already begun in 1933 when the Nuremberg Laws defined Jews as second-class citizens. Between 1937 and 1939, Jews were forced out of Germany’s economy. At this time children were not allowed to attend public schools, Jewish-owned shops were looted and destroyed, Jewish citizens could not attend cinemas or theaters, and Jews were even forbidden to walk in certain areas in Germany.

Eva Hesse was thus born into a life that was synonymous with high-strung tension and fear.

Her father had lost his profession soon after Eva Hesse’s birth and by the age of two years old, Eva Hesse and her sister, Helen, were placed aboard one of the last trains that would take children out of Germany. The children were not allowed to be accompanied by their parents and the two sisters, aged two and five, made this journey by themselves towards the Netherlands.

The plan was that their aunt and uncle would collect them from the train station in the Netherlands, but by the time the Hesse sisters arrived, their aunt and uncle had already been segregated and the sisters were sent to a children’s home. The girls stayed here for six months until their parents were able to flee Germany. After being collected from the children’s home, the Hesse family emigrated to New York City. Eva Hesse’s aunt, uncle, and grandparents were all killed by the Nazi regime.

The prosecution of their extended family had affected Eva Hesse’s mother drastically.

Her mother, who was already suffering from bipolar disease, could not cope with her suffering and the manner of death of her parents. On top of this, Hesse’s parents got divorced and her father remarried in 1945. Her mother committed suicide in 1946 when Eva Hesse was only ten years old. The suicide of her mother had traumatized Eva Hesse for years and she led an incredibly challenging childhood, struggling with her mental health and fear of abandonment.

Her new stepmother, also called Eva, took young Eva Hesse to therapy, and although this helped the young Hesse a lot, she never really got along with her stepmother. After the wedding, Eva Hesse’s stepmother now shared her own name and surname, leaving young Hesse with even more psychological turmoil. Hesse was unsure of her identity, her place, and her importance in the world.

Eva Hesse struggled with anxiety and identity issues for the rest of her brief life. This is something that can really be felt in her early works.

Education and Early Career

Eva Hesse’s biological mother was also an artist and her father was not in full support of her choice, urging her to pursue a more stable career. Regardless of this, Hesse left her home at the age of sixteen to pursue a career in art. At first, she attended Pratt Institute but did not enjoy their approach to teaching art. She enrolled at Pratt Institute in 1952, only to drop out a year later. When Hesse was 18, she started an internship at Seventeen magazine.

This was a job that she enjoyed and that gave her more confidence in her own work. During this time, she continued to take art classes with the Art Students League.

The most important years of her education were when she studied at Yale, where she was greatly influenced by her lecturer Josef Albers. It is also during her Yale years that Eva Hesse met artist Sol LeWitt. LeWitt and Hesse became great life-long friends. She also made friends with other young artists, including Yayoi Kusama and Donald Judd. Hesse graduated from Yale in 1959 and in 1961 she married the sculptor, Tom Doyle.

Hesse and Doyle worked together and often exhibited together.

They both participated in an “Allan Kaprow Happening” in 1962. These “Happenings” were events where artists, dancers, and performers would come together to create weird and wonderful things. It was at this happening in New York where Eva Hesse showcased her first three-dimensional work. This work was a costume for the happening, a long and large worm-like textile sculpture/costume where multiple people could stick their heads through the holes and move in unison, giving life to the sculpture.

The Transforming Years and Mature Works

Eva Hesse had her first solo show in 1963 in New York City, where she showcased works on paper at the Allan Stone Gallery. Soon after this, her husband, Tom Doyle, was asked by collector Friedrich Arnard Scheidt to do an artist residency in Germany. In 1965 the couple moved to Germany for the artist’s residency. Although both artists were provided with a studio, Hesse was not happy about the move, her childhood memories of the county crippling her with fear.

She was, however, committed to both her husband and her career, and she decided to immerse herself in her work.

The studio that was provided to them was situated in an abandoned textile mill, where old machine parts and materials inspired her. Hesse’s paintings during this time were inspired by these machines and it signaled a turning point in her career. It is while working in this studio that Eva Hesse received the letter that Sol LeWitt famously wrote to her, urging her to stop obsessing so much and just “do”. LeWitt’s advice helped Hesse to create without overthinking, and the result was beautifully unique and strange paintings and sculptures.

This was an important turning point in Eva Hesse’s work, and from here on she identified as a sculptor.

When Hesse and Doyle returned to New York in 1965, their relationship had deteriorated heavily. Doyle was very social and often attended exhibitions and openings without her. He had drunken habits and often left her feeling alone. For someone struggling with anxieties around abandonment, this was especially difficult for Hesse. Doyle and Hesse got divorced in 1966. After Hesse no longer had the role of “wife”, she gave all of herself to her work. She started experimenting with exciting new mediums, such as polymers, rubbers, silicone, fiberglass, latex, resin, and plastic.

These works became so characteristic of her mature works, giving her work a sense of mystery and innovation.

The Minimalism and Feminism in Eva Hesse’s Work

Eva Hesse’s sculptures in these unique materials were inspired by minimalism but had a warmth and intimacy that minimalist art did not have. Her work carried a distinct presence of the artist’s hand in them, it had a sensual quality and contained early influences of surrealism and absurdity. Working in a primarily male-dominated New York art scene of the 1960s and 1970s, Eva Hesse’s sculptures had a sensuality that differentiated her work from the rigidity and impersonal symmetry of the male artists working in minimalism.

With her more personal touch, Eva Hesse’s sculptures took a respectful departure from minimalism and urged on the movement of post-Minimalism.

Eva Hesse’s work had a distinct female quality to it, something that she embraced and owned. She was an advocate for female artists and strongly believed that excellence had no gender. She got angry when articles on group exhibitions wrote more about the male artists than about her work. She felt frustrated when she was referred to as a “female artist” and insisted that she is simply an artist.

Male artists were simply referred to as “artists”, not as “male artists”, and Hesse believed that there should be no distinction made between her and her fellow male artist. She believed that she should carry the same title and be given the same amount of space as male artists.

Eva Hesse’s Most Important Exhibitions

Eva Hesse’s paintings were the first of her work to be exhibited. In 1961, Hesse showcased a series of gouache paintings at the Brooklyn Museum’s 21st International Watercolor Biennial. In the same year, she showcased drawings at an exhibition titled Drawings: Three Young Americans, hosted by the John Heller Gallery in New York. Eva Hesse’s first solo show was at the Allan Stone Gallery in New York City in 1963. Eva Hesse’s sculptures were first shown in 1965 in a solo show in Düsseldorf at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen.

The exhibition that truly secured Eva Hesse’s stardom was an exhibition titled Chain Polymers in the Fischbach Gallery in New York City. This exhibition featured large-scale sculptures and was the only solo sculpture exhibition that Hesse would have during her life in America. One of her works in this exhibition, titled Expanded Expansion, traveled to the Whitney Museum where it was showcased in 1969 in a show called Anti-Illusion: Process/Materials.

Hesse’s works continued to be exhibited in many prestigious spaces after her death.

Among these are exhibitions at the Guggenheim Museum in 1972. In 1979 there were three retrospective exhibitions held for Eva Hesse’s lifetime of work. These exhibitions were titled Eva Hesse: Sculpture and were shown at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London, the Kroller-Muller in Otterlo, and the Kestner-Gesellschaft in Hannover.

The first retrospective only focussing on Eva Hesse’s drawings was held in the Grey Art Gallery in New York City, and traveled to the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston.

There were many other exhibitions and retrospectives held in the years to follow that included Eva Hesse’s paintings, sculptures, and drawings. One of these was a major exhibition that opened in 2000 that was jointly organized by the Tate Modern, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Museum Wiesbaden.

The Conservation and Collection of Eva Hesse’s Work

Eva Hesse’s work was often made in materials that did not promise longevity. She was not worried so much about the conversation aspects of her work and believed that just as life doesn’t last, art also doesn’t last. Part of the reason Hesse used the materials that she did, was because she loved the strangeness and immediacy of it.

Hesse’s artworks were reflective of the times and she created them to be present and to be enjoyed in the moments after their creation, and not meant for the admiration of viewers a hundred years later.

Regardless of this, Hesse’s works are held in numerous collections, and while there are many efforts to preserve her work as well as possible, some cannot ever be shown in the same way it was made. Below is a list of some of the institutions that have Eva Hesse’s work in their collections:

- The Museum of Modern Art (New York, United States of America),

- The Museum Wiesbaden (Wiesbaden, Germany),

- The Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College (Ohio, United States of America),

- The Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, United States of America),

- The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (Washington D.C., United States of America),

- The National Gallery of Australia (Parkes, Australia),

- The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (California, United States of America),

- The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (New York, United States of America),

- The Tate Modern (London, United Kingdom),

- The Jewish Museum (New York, United States of America), and

- The Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, United States of America).

Seminal Works of Eva Hesse

Eva Hesse’s works developed rapidly in a very short period. Her transition from Abstract Expressionism and Surrealism to her Postminimalism works took place over 5 short years. In these 5 years, Hesse produced a remarkable amount of work. The works are a small list of numerous incredibly successful pieces. Select works from the list below will be discussed in more detail in the sections to follow.

- Tomorrow’s Apples (5 in White) (1965)

- Ringaround Arosie (1965)

- Hang Up (1966)

- Untitled or Not Yet (1966)

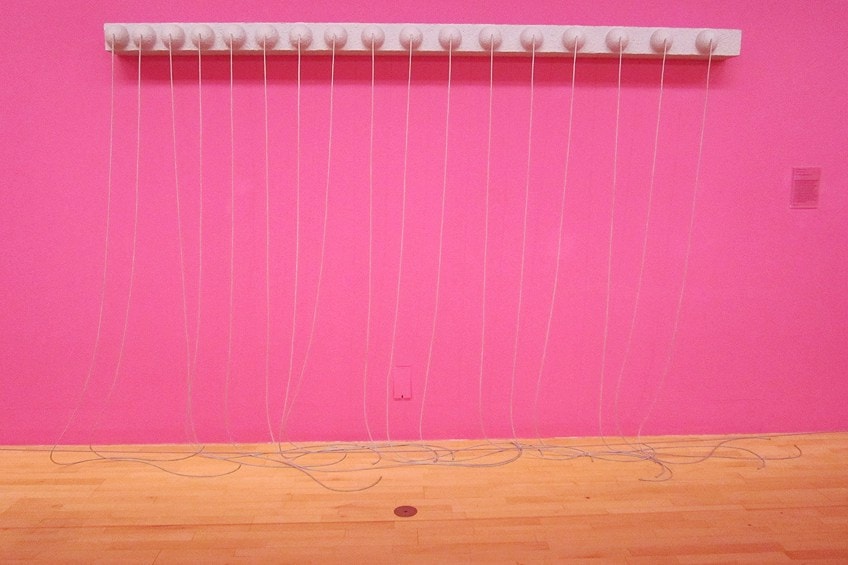

- Metronomic Irregularity II (1966)

- Addendum (1967)

- Repetition Nineteen III (1968)

- Contingent (1968)

- Sans II (1968)

- Accession II (1968-1969)

- Expanded Expansion (1969)

- Right After (1969)

Ringaround Arosie (1965)

| Artwork Title | Ringaround Arosie |

| Date | 1965 |

| Medium | Pencil, acetone, varnish, enamel paint, ink, and cloth-covered electrical wire on paper-mâché and masonite |

| Size | 67 x 41.9 x 11.4 cm |

| Collection | The Museum of Modern Art, New York |

Ringaround Arosie is one of the first of Hesse’s works that transcended two-dimensional painting and embraced more sculptural aspects. This powerful Eva Hesse artwork indicates the influence of Abstract Expressionism and Surrealism in her early career. Eva Hesse’s paintings often had strange shapes and strong colors, with unique and powerful compositions, and Ringaround Arosie is no different.

The work is playful and embedded with erotic surrealism. Some link the work to the absurd qualities found in the Dada works of Duchamp and his contemporaries.

The work has almost a humorous sexual quality to it, which is a strange contrast to the title of the piece, which refers to the haunting childhood game that referenced falling, death, and calamity. Some argue that this came about in Eva Hesse’s desires and fears of motherhood and the wanting, at the time, to become a mother herself. The work also pays tribute to Rosalyn Goldman, who is one of Eva Hesse’s friends who fell pregnant. This is one of 14 relief-like works that the artist created in Germany. When Eva Hesse returned to the United States, she declared herself to be a sculptor.

Hang Up (1966)

| Artwork Title | Hang Up |

| Date | 1966 |

| Medium | Acrylic on cloth over wood, acrylic on cord over steel tube. |

| Size | 182.9 x 213.4 x 198.1 cm |

| Collection | The Art Institute of Chicago |

Hang Up (1966) is a work that Eva Hesse considered to be one of the most important works she created at the time, as it was both incredibly absurd and still full of feeling. The work consists of a frame, wrapped with bedsheets, with a limp cord protruding from the frame and taking up so much space that it became an obstacle for the audience to navigate around and through the work.

Artists and critics called the work audacious and absurd, whilst praising it to be one of the greatest sculptures of the time.

Lucy Lippard, an art critic and also a friend of Eva, included the work in a later exhibition titled Eccentric Abstraction. In this exhibition, Eva Hesse showed alongside artists like Louise Bourgeois and Bruce Nauman at the Fischbach Gallery. This seemingly simple addition to the exhibition transformed a painting into a sculpture and was highly symbolic of where Eva Hesse was in her artistic development.

Accession II (1968-1969)

| Artwork Title | Accession II |

| Date | 1968-1969 |

| Medium | Galvanized steel and vinyl |

| Size | 78.1 x 78.1 x 78.1 cm |

| Weight | 53.1 kg |

| Collection | The Detroit Institute of Arts |

Accession II is a part of a series of Accession works that Eva Hesse created. This specific work in the Accession series is considered to be the most succinct in the series, and it carries a strong reference to Eva Hesse’s earlier paintings of square structures. The work is an industrial-looking square metal box that stands large on the floor. The outside of the box seems purely minimalist, rigid, and cold. The box, however, is open at the top and reveals rows of tubing of vinyl and rubber, densely sticking out inside of the box. The tubing is quite sensual and sexual, whilst simultaneously feeling slightly threatening.

The work feels quite contradictory: soft yet hard, inviting yet repelling. This pull of binary opposites rang true to the artist’s own, often contradictory, psychological headspace.

Right After (1969)

| Artwork Title | Right After |

| Date | 1969 |

| Medium | Fiberglass |

| Size | Approx. 152.39 x 548.61 x 121.91 cm |

| Collection | Hauser & Wirth |

Right After is one of Eva Hesse’s final artworks. The work is a massive web-like structure of fiberglass cord dipped into latex and suspended in space. She finished the work after she returned home from the last operation she would have before passing away. This work seems less concerned with extremes and binaries than her Accession works, possibly because the artist at the time of making this work had accepted that one has so little control over one’s life.

In this work, it is as if she let go of wanting control and simply allowed the artwork to, in some way, create itself.

It is as if Eva Hesse simply followed the cord and allowed it to go wherever it wanted to go. Because of this, the work has a feeling of the Abstract Expressionists’ ideal of the “sublime” embedded within it. The soft lines and droopy structure of the work make it seem like it is reaching out to the audience, it is a work that wants to be examined up close.

What is so wonderful about this work, and in many of Eva Hesse’s other works, is that there is nothing alienating or standoffish about the work, rather, there is a kind of embrace in the work. It is as if Hesse started a conversation by making the work, and if the conversation continues when the audience interacts with the work.

The work seems to say that there is a bond holding us together. This bond can be read in terms of the literal bonding of liquids and network-like structure of the work, the bond between artist and viewer, or even the global bond that connects human beings with each other.

Book Recommendations

There are some truly incredible books available on the life and work of Eva Hesse as an artist who is deserving to be remembered. Eva Hesse is an artist that people from different disciplines can truly be inspired by. If you are interested in learning more about the work and life of Eva Hesse, we recommend starting with these marvelous publications.

Eva Hesse (1992) by Lucy R. Lippard

Lucy R. Lippard is an acclaimed American art critic and writer. She was also a very good and close friend of Eva Hesse. As her friend and someone who deeply understands the art of the 20th century, Lucy Lippard is able to provide a personal insight into the work of Eva Hesse. This is a book that truly resonates with the reader and makes it clear why Eva Hesse was such an incredible artist.

- Designed by the artist's friends and colleaugues

- Hesse's works are reproduced and discussed

- Text includes numerous quotations from her diaries

Converging Lines: Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt (2014) by Veronica Roberts

This book gives a rich insight into the special friendship and working relationship between Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt. The book shows love in their friendship and the extent to which they influenced each other’s works. The book is rich in documentation and includes letters shared between the artists, a recollection of memories by their good friend Lucy R. Lippard, who is also an acclaimed writer and art critic. The book includes previously unpublished interviews, postcards, and photographs.

- A fascinating glimpse into the friendship of two acclaimed artists

- An illuminating look at the circle of Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt

- Richly documented with letters and postcards

Eva Hesse: Oberlin Drawings: Drawings in the Collection of the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College (2019) Edited by Barry Rosen

This book offers a generous reproduction of Eva Hesse’s artworks, focusing specifically on the artist’s drawings. The book won the New York Times critic’s pick for “Best Art Books 2020”. Eva Hesse’s drawings play a huge role in how her work developed, and this book explores just how important drawing was in the artist’s practice.

- A generous and indelible assortment of works on paper

- Contains the entirety of the artist's drawings held at the AMAM

- A monumental tome covering the oeuvre of artist Eva Hesse

Eva Hesse’s anxieties, existential and artistic, became important aspects of her artistic work and development as she strived to find and express herself through her art. In the end, her work found a way to provide the world with something that no other artist at the time could provide: a new approach to Minimalism. She provided the world with work that is simultaneously very strong formally, but also poetic, intimate, and emotional. Her art made a statement that showed just how important the artist’s presence is in their work and by being so thoroughly involved in the materials she used. Eva Hesse embedded her work with so much feeling and connection, that even after she was gone, her presence and spirit can still be found within her work.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Old Was Eva Hesse When She Died?

Eva Hesse was 34 years old when she passed away. She was born in 1936 in Hamburg, Germany, and died in New York City in 1970 from a brain tumor. She passed away after three unsuccessful surgeries in one year.

What Was the Nature of Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt’s Relationship?

Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt were great friends. They often wrote long letters to each other and were each other’s confidants and advisors. Both artists declared that they loved the other, but Hesse said that LeWitt was like family for her and saw him as her brother. Sol LeWitt named his daughter after Eva Hesse and Eva LeWitt also became an artist.

Was Eva Hesse the Artist a Minimalist?

Eva Hesse’s sculptures are greatly influenced by Minimalism. Her work, however, is seen as having surpassed Minimalist ideals and Eva Hesse is an artist now associated with Postminimalism. The difference is that Minimalism supports highly rigid and precise impersonal concepts that are purely focused on the formal qualities of the sculptural form and symmetry. Eva Hesse’s works are respectful of Minimalist ideals and her work is seen as highly formal, but it has a more personal aspect and imperfect marks created by the artist’s hands, resulting in less rigid and more personal artworks.

Chrisél Attewell (b. 1994) is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. Her work is research-driven and experimental. Inspired by current socio-ecological concerns, Attewell’s work explores the nuances in people’s connection to the Earth, to other species, and to each other. She works with various mediums, including installation, sculpture, photography, and painting, and prefers natural materials, such as hemp canvas, oil paint, glass, clay, and stone.

She received her BAFA (Fine Arts, Cum Laude) from the University of Pretoria in 2016 and is currently pursuing her MA in Visual Arts at the University of Johannesburg. Her work has been represented locally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, residencies, and art fairs. Attewell was selected as a Sasol New Signatures finalist (2016, 2017) and a Top 100 finalist for the ABSA L’Atelier (2018). Attewell was selected as a 2018 recipient of the Young Female Residency Award, founded by Benon Lutaaya.

Her work was showcased at the 2019 and 2022 Contemporary Istanbul with Berman Contemporary and her latest solo exhibition, titled Sociogenesis: Resilience under Fire, curated by Els van Mourik, was exhibited in 2020 at Berman Contemporary in Johannesburg. Attewell also exhibited at the main section of the 2022 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Learn more about Chrisél Attwell and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Chrisél, Attewell, “Eva Hesse – The Sculptor Who Brought Life to Minimalism.” Art in Context. April 4, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/eva-hesse/

Attewell, C. (2022, 4 April). Eva Hesse – The Sculptor Who Brought Life to Minimalism. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/eva-hesse/

Attewell, Chrisél. “Eva Hesse – The Sculptor Who Brought Life to Minimalism.” Art in Context, April 4, 2022. https://artincontext.org/eva-hesse/.