What Paintings Are in the Louvre? – Exploring the Best Louvre Artworks

Have you ever wondered what paintings are in the Louvre? Did you know that currently there are over 7,500 Louvre paintings? But are the paintings in the Louvre real or replicas? Today we will be looking at a few remarkable Louvre artworks as well as the museum itself.

An Introduction to the Louvre Museum

The Louvre Museum opened in 1793, displaying the French monarch’s art collection as well as the results of Napoleon’s Empire’s pillaging. Since its inception, the museum has been open to the public on select days of the week, which was considered groundbreaking at the time. The Louvre Palace is home to the largest museum in the world. Throughout the decades, the 12th-century castle was enlarged and renovated multiple times.

Before it became a museum, King Charles V and Philippe II lived in this palace, which they decorated with their ever-expanding art collection.

Once the royal family relocated to Versailles, the majestic 160,000-square-meter structure was turned into one of the world’s most significant museums. In 1989, a glass pyramid, which now serves as the museum’s main entrance, was created in the palace’s main courtyard, breaking up the uniformity of the Louvre’s facade.

The Louvre’s official collection contains almost 300,000 artworks from before 1948, only 35,000 of those are open to the general populace.

The vast collection is divided into many categories, including Oriental Antiquities, Greek Antiquities, Egyptian Antiquities, and Roman and Etruscan Antiquities. The museum also features a section on the real palace’s history, such as the Louvre throughout the Middle Ages, Islamic artwork, paintings, statues, and graphic art. Guests will need an entire morning to obtain a rough sense of the Louvre and view the most notable paintings, sculptures, and other sorts of art. The Louvre is so large that touring its displays might easily take many days.

The Most Famous Paintings in the Louvre

There are literally thousands of Louvre artworks, however, there are a few that could be considered the most famous paintings in the Louvre. What paintings are in the Louvre that you can name? Let us now take a deeper look at some of the most well-loved Louvre paintings.

St. Francis of Assisi Receiving the Stigmata (c. 1300) by Giotto di Bondone

| Date of Completion | c. 1300 |

| Medium | Tempera on wood |

| Dimensions | 313 cm x 163 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

If you’re familiar with Byzantine art, you might agree that it can be a touch monotonous. The art style is characterized by “rigid” figures devoid of feeling. Byzantine art is easily identified since it mainly depends on gold leaves, as seen above. If you’ve seen one Byzantine artwork, you’ve seen them all, which is why everyone admires the last one ever created. Giotto’s picture is not the final Byzantine painting ever produced, but it marks the start of the end of this art form.

Giotto presents more emotional characters that connect with one another and give a certain tale. This concept would become the Renaissance’s core.

When standing in front of Giotto’s famous masterpiece, you can readily comparisons to the other Byzantine paintings in the same Louvre room. Giotto’s figures connect with one another more, show more emotions, and create a little more impassioned tale. Giotto would fresco the Scrovengi Chapel, which was rich in color and presented a huge tale.

The chapel propelled the arts closer and closer to the Renaissance era, which generated many of the globe’s most renowned pieces of art, several of which are now held in the Louvre.

The Virgin of the Rocks (1483 – 1486) by Leonardo da Vinci

| Date of Completion | 1483-1486 |

| Medium | Oil on wood |

| Dimensions | 199 cm x 122 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

This painting’s magnificence is concentrated in a few important spots. First, there is an almost similar artwork with a few crucial modifications in London, which is a typical thing of the artist to do. Uriel’s finger is not extended in the London artwork, and the colors are changed. It may seem like a minor point, but consider how much dispute Judas’ extended finger in Da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1495-1498) causes.

That leads to the artwork’s second criticism, which is the painting’s flow. The figures form a triangle shape, which causes the eyes to move from one point to another.

Your gaze may be drawn to various parts of the picture, but there is a continuous movement from Uriel’s hand to John, Mary, and back again. The soft characteristics of each person’s face come in third. When this was disclosed, it was like trying to compare the clarity of a film from the 1980s to one from this year. Da Vinci was an expert at sketching figures. Finally, there’s the background, which is full of jagged rocks and a “Lord of the Rings”-style countryside.

Why were they placed in this wonderful world? Da Vinci’s purpose, like today’s social media, was to grab and take your attention.

Minerva Expelling the Vices From the Garden of Virtue (1502) by Andrea Mantegna

| Date of Completion | 1502 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 160 cm x 192 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

Minerva Expelling the Vices From the Garden of Virtue is one of the artist’s most spectacular works. It depicts a towering fence enclosing a wetland. The victory of the vices demonstrates that the vices have an advantage in governing the enclosure. There is proof of horrible beings who rule the fence as vices. These heinous characters, as shown, can only be medieval. This is due to the prevalence of scrolls in medieval times. Diana is shown being saved by Minerva, who is shown chasing laziness. Diana, as the goddess of virginity, must not be violated, like a Centaur, a sign of sinful nature, is depicted attempting.

Just beside Minerva, there is a tree with human qualities and theological virtues, Justice, Temperance, and Fortitude. These are the moral ideals that are seen as fundamental and essential in the lives of any human being.

This effort is done tactically to ensure that the desired emotions are produced. There is a conscious attempt to depict the vices that were attempting to infiltrate the paradise of virtues. As the virtues win, these vices are shown being chased out of the garden. This is a difficult undertaking since the vices dominate the garden and rule it. Minerva will have to put in a lot of effort to win this duel.

Looking closely at the victory of virtues, it is clear that vices can never win over virtues if there is a desire to eject them.

The vices are portrayed as being chased out of the garden. Traditional art has frequently provided moral direction, whether through depictions of religious subjects or by directly mirroring the artist’s personal sentiments. Religion would control art for many generations, in part because these organizations would be among the wealthiest in Europe, allowing them to hire the best painters available.

The Battle Between Love and Chastity (1503) by Pietro Perugino

| Date of Completion | 1503 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 160 cm x 191 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

This piece is an allegorical one, illustrating the internal conflict that our European forefathers endured. Do you save up for a loveless marriage or do you appreciate your sexual liberties now? Because our culture does not need virginity before marriage as it did in the 15th and 16th centuries, we may not comprehend the artwork. Arranged marriages that start without love are also no longer a part of Western culture, therefore this image is even more removed from reality.

The theme was proposed by Isabella’s court poet, Paride da Ceresara, and is attested through Isabella’s communication with Perugino, who was active in Florence at the time.

The notary agreement included the literary concept as well as a sketch on which the work was to be based. The Marchesa, for example, was outraged when Perugino depicted a nude Venus rather than a clad Venus. When the artwork was delivered in 1505, the Marchesa was dissatisfied. She stated that she would have liked it to be created in oil rather than the tempera employed under her direction to mimic Mantegna’s technique. Perugino, who was undoubtedly uncomfortable with the work’s modest format, was paid 100 ducats for it.

The picture depicts a conflict between the allegorical characters of Love and Chastity against a landscape of gently sloping hills.

St. Michael Overwhelming the Demon (1518) by Raphael

| Date of Completion | 1518 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 268 cm x 160 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

Raphael’s oil painting of St. Michael is well-known to millions of people. Although most people recognize this picture, they are unaware of its significance. The picture depicts Archangel Michael surrounded by devils. He has wings and a halo affixed to him and is encircled by the gloomy and dreary depths of hell. There are demonic captives on the earth beneath St. Michael’s feet, and he fights the demons around him with a shield and a long sword. Angels can be seen in the painting’s backdrop. All of the condemned behind him are in pain.

The actual cause for the piece’s creation is unknown, however, there is one widely accepted theory.

According to legend, the painting was commissioned to convey the duke’s appreciation to Louis XII of France. Raphaello Sanzio da Urbino was a brilliant master of his day and an Italian painter who possessed a huge workshop.

During his brief life, he produced a number of works of high art. Most of his works are still on display across the world, notably inside the Vatican.

The Wedding Feast at Cana (1563) by Paolo Veronese

| Date of Completion | 1563 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 677 cm x 994 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

The Wedding Feast at Cana, a biblical narrative, recalls Christ’s first miracle. While he is called to a wedding supper in Cana, the wine runs out at the conclusion of the meal. The slaves were then told by Jesus to fill huge stone jugs with water and then serve the lord of the house. He is startled to see that the water has changed into wine! This religious episode is reimagined as a lavish Venetian wedding. Surprisingly, Christ is positioned in the middle of this wedding scene, flanked by the Virgin and the apostles, with the groom and bride to the left.

Furthermore, Christ’s commanding figure is emphasized by his unwavering glance at the observer.

The bride is likewise glancing at us, but does she appear to be happy? No, since there isn’t any more wine at her feast. And why does the groom appear to be thinking? His demeanor may be linked to the butler’s pose in his green tunic: he uncurls his belt, with his left hand on his pouch, he is enraged: his task has been insulted, and he returns his clothes in the center of the banquet; the groom does not know what else to say and tastes the wine despite not knowing where it came from.

A man in blue, with a huge nose and red cheeks, stands next to the bride.

Is he looking at the bride’s bosom? No, he holds a full cup in his left hand, he chats to the servant sporting a bell cap, and he speaks about wine: it appears that he is moaning – perhaps he still has the older wine in his glass and wishes to taste the new one?

Death of the Virgin (1606) by Caravaggio

| Date of Completion | 1606 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 369 cm × 245 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

The picture was originally commissioned for Santa Maria della Scala in Rome, but it was turned down. The picture was most likely denied because it was rude. Jesus and the Apostles did not have money, as this artwork illustrates. Caravaggio frequently hired beggars, prostitutes, and other poor people to pose for him. He experienced a horrible and poisonous existence, which is reflected in his paintings. His portrayal of the encounter with the Queen of Christendom is most likely more authentic than any other story.

Its intense passion, bare feet, solemn looks, and colorless Mary body did not meet the concept of the Virgin’s final hours on Earth, and it was therefore discarded.

The Apostles’ faces are filled with uncertainty as they stare at her. The last link to the savior Jesus Christ has been severed, and they are now alone. Mary Magdalene leaned to one side, her head in her hands. A sign of uncertainty and doubt shared by two other apostles. Behind the two unsure and unhappy apostles, Peter is most likely on her side. It’s difficult to tell because the traditional imagery of the keys to heaven isn’t in his hands.

Nonetheless, the figure exudes urgency and confidence. Peter was Jesus’ successor and the first Pope, so it will be his responsibility to unite the group.

David With the Head of Goliath (c. 1605) by Guido Reni

| Date of Completion | c. 1605 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 220 cm x 160 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

Guido Reni, a Bolognese painter, is often credited with codifying a sort of ideal, “classic” beauty in the 17th century, focusing on the harmony of proportions and drawing. This innate leaning toward classicism was the product of his schooling, which was inspired by Raphael’s models and filtered via the techniques of Bolognese artist Carracci. Guido, who was already an accomplished artist, enrolled at the renowned Accademia degli Incamminati, a painting school. It aimed to follow in the footsteps of the great Masters of the 16th century by focusing on anatomy and life drawing.

Guido Reni retained the light-filled serenity and figurative precision that have frequently led to his works being juxtaposed against the realism and dark dramatic manner of the Caravaggisti throughout his illustrious career.

Reni did, however, develop an openness to Caravaggio’s colors and methods after moving to Rome in the early 17th century, adopting some of the more superficial features, such as the stark contrasts of light or the fondness for historical images tied to bloody occurrences.

A certain frigid coldness pervaded his figures, which retained aspects of melancholic grace even in their most rudimentary positions.

David strikes a dandy position, with a red feathered hat and his body lit by a moonlike light and barely concealed by a beautiful cloak trimmed with fur; the light delicately outlines his figure, while the shadow is radiated from the backdrop. The boy is studying Goliath’s severed head; the event has already occurred, and the drama has dissolved into meditation.

The Rape of the Sabine Women (1638) by Nicolas Poussin

| Date of Completion | 1638 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 206 cm x 159 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

This Roman mythological story dates back to Romulus’ time. Women were in scarce supply in the newly created colony of Rome. To solve the situation, the Romans approached the nearby Sabine tribe, but they forbade their women to marry Romans. So, the Romans prepared a big feast during which they kidnapped the Sabine ladies and drove off the defenseless Sabine men at a pre-arranged signal. In response, the Sabines and their allies launched a war against Rome.

After their friends were beaten in battle, the Sabines assaulted Rome, sparking a furious struggle that caused the Sabine women to intercede and plead for peace.

After the war, the Sabines decided to form a single country with the Romans. Throughout the Italian Renaissance and later, the narrative was represented in countless artworks. Nicolas Poussin created two versions of this fable, one of which is currently housed in the Metropolitan Museum and the other in the Louvre in Paris. Both pieces illustrate the artist’s powerful and aggressive technique, which he used in many of his subjects from ancient history.

Although both renditions of the artwork are basically identical – Romulus provides the pre-arranged message in both, and anarchy covers the canvas – there are changes in composition and color. The artwork in the Met is more structured, static, and colorful, but the one in the Louvre is more fluid and has more dimension.

Poussin emphasizes the terror and conflict between the women and men in the Louvre version, against an architectural background that leads our gaze into the horizon with diagonals generated by the structures on the right.

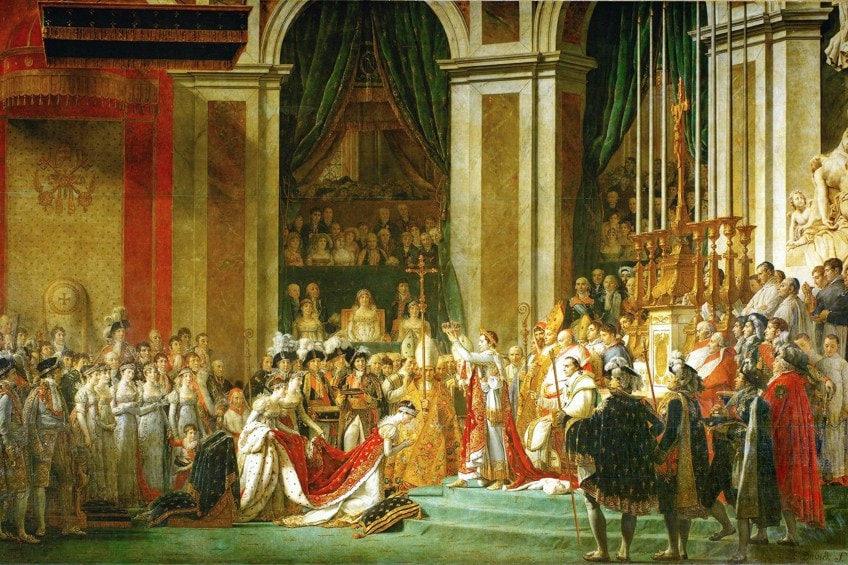

Coronation of Napoleon (1807) by Jacques-Louis David

| Date of Completion | 1807 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 621 cm x 979 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

Napoleon stands in the center, carrying the crown, and is preparing to crown his wife, Joséphine. Joséphine is reclining on a cushion, while Napoleon is dressed in his coronation garment, which mimics the robes used by Roman emperors. Pope Pius VII is sitting to Napoleon’s right.

He approves of the coronation, but only reluctantly because of Napoleon’s coercion.

Napoleon’s mother is seated in the center of the artwork, dressed in a white gown. Napoleon’s brothers, two similarly clothed gentlemen in the left foreground, are wearing black caps. To the right of Napoleon’s two brothers are his three sisters, who are also clothed similarly.

Julie Clary, Joseph Bonaparte’s wife, and Hortense, Joséphine’s daughter, stand to the right of Napoleon’s three sisters. They are also outfitted identically. David portrayed himself as he observed the coronation in the backdrop. Finally, all 204 faces in the picture appear solemn, emphasizing the significance of the occasion.

The fact that it occurred in Notre Dame Cathedral added to its significance.

Furthermore, the Pope personally was there for the ceremony, and not by choice. After the defeat of Papal soldiers in 1796, Napoleon took authority of Rome and dragged the Pope to France, where he passed away in 1799. The future Pope, Pius VII, did not like Napoleon, as seen by his solemn expression in the artwork (the only person seated).

The Raft of the Medusa (1819) by Théodore Géricault

| Date of Completion | 1819 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 491 cm x 716 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

The French Revolution sparked a surge in interest in depicting current events, but following Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, few painters were willing to tackle such topics. Géricault was an outlier, although he was distinguished from his predecessors by temperament as well as honesty of approach. The Raft of the Medusa powerfully depicts individual anguish rather than group drama.

It represents the aftermath of the 1816 sinking of the French Royal Navy ship Medusa off the coast of Senegal. Due to a lack of lifeboats, 150 survivors boarded a raft and were devastated by malnutrition during a 13-day ordeal that devolved into violence and cannibalism.

When they were saved at sea, just a few remained. The shipwreck had shocking political ramifications in France—the inept captain, who had risen to the position due to links to the Bourbon Restoration authorities, battled to save himself and senior officers while abandoning the lower ranks to perish—and thus Géricault’s painting of the raft and its residents was met with antagonism by the government.

The painting’s gruesome realism, presentation of the raft catastrophe as epic-heroic tragedy, and the mastery of its drawing and tonalities all work together to elevate it well beyond conventional contemporaneous reportage.

The depiction of the dead and dying, built inside a dramatic, meticulously crafted composition, addressed a topical issue with amazing and unparalleled fervor.

Géricault displayed the painting at the 1819 Salon, the Louvre’s annual exhibition of modern French art. It received a gold prize, but many critics panned the gruesome subject matter and repulsive realism. Géricault, dissatisfied with the reception of The Raft of the Medusa, transported the painting to England in 1820, where it was a phenomenal success. Following Géricault’s death in 1824, Louvre director Comte de Forbin bought the painting from Géricault’s heirs for the museum.

Dante and Virgil in Hell (1822) by Eugène Delacroix

| Date of Completion | 1822 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 189 cm x 241 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

Dante Alighieri is often regarded as the most important early Renaissance writer or poet. The Divine Comedy, an epic poem written in the embryonic Italian language, effectively put writing back on the map. He produced the first major book since the Roman Empire’s demise 700 years before. The Divine Comedy is a three-part epic poem that describes Heaven, Purgatory, and Hell. Eugène Delacroix’s painting of hell is one of the most intriguing since nearly everyone on Earth is terrified of it. It’s worth noting that your dread of hell stems from The Divine Comedy and artworks like Delacroix’s depictions of it.

Dante was among the first to vividly depict Hell, and art transformed those descriptions into visuals, which is why we are so scared of Hell in the first place.

Also referred to as The Barque of Dante, this was Delacroix’s first big picture, and it was quickly embraced and acclaimed by supporters of the Romantic movement. It is a dramatic allegory starring Dante in his red cap and Virgil, a Roman pagan writer who offered him history’s tour of hell!

You may recognize Michelangelo’s impact on Delacroix if you visit the Sistine Chapel. With over 300 years between them, Michelangelo was as old to him as we are to him, yet his effect was enormous.

The “condemned” are depicted as enormous muscular individuals floating in the ocean, nearly alive but not dead. The demons are shown as more aggressive yellow creatures nibbling on the side of the vessel and generally instilling terror in everyone around them.

Liberty Leading the People (1830) by Eugène Delacroix

| Date of Completion | 1830 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 260 cm x 325 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum |

The French Revolution was an era of political and societal upheaval in the late 18th century that engulfed the country. The storming of the Bastille marked the official start of the revolution. On this day, a mob of rioters, largely artisans and shop owners, stormed the Bastille, a historic fortress-turned-state jail. The rebels planned to acquire access to the gun powder stored on the property in addition to liberating political prisoners.

What were these rioters protesting? Finally, they were dissatisfied with France’s royal family, whose overwhelming luxury highlighted—and exacerbated—their own misery. France’s citizens were struggling to feed themselves and their families because they were overtaxed and underpaid, resulting in a series of fights.

Delacroix created Liberty Leading the People in 1830, the same year when the July Revolution altered the trajectory of French history.

This fight, like those fought throughout the French Revolution, arose as a result of opposing opinions on who should lead France. On this occasion, both factions backed the House of Bourbon or the House of Orléans. Charles X of the House Bourbon had been in power since 1824 at this point. However, after a three-day fight, he was deposed and replaced by Louis-Philippe, a member of the House of Orléans.

The large-scale picture, set in the streets of Paris and loaded with symbolism, depicts Parisians pursuing a female figure.

This allegorical character, intended to reflect the notion of liberty, is widely thought to be an initial prototype of Marianne, a representation of the French republic. All of the characters are positioned in a pyramid shape, with Marianne at the top, emphasizing her prominence in the composition and directing the viewer’s gaze across the painting’s canvas.

What did you think of our list of the most famous paintings in the Louvre Museum? There are many Louvre artworks to choose from, but we feel this list of Louvre paintings features some of the more highly appreciated works of art. To this very day, they are enjoyed by thousands of visitors per month.

Take a look at our Louvre paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Paintings Are in the Louvre?

The Louvre is full of thousands of well-known paintings and artworks. There would be too many to mention here. We suggest going to pay the museum a visit for yourself to check out their selection or have a look through our list of some of the best works you can discover.

Are the Paintings in the Louvre Real?

You might think that all the paintings in the museum are authentic. However, new evidence has suggested otherwise. According to a current study, more than half of the pieces in the Louvre Museum’s collection appear to be forgeries.

Nicolene Burger is a South African multi-media artist, working primarily in oil paint and performance art. She received her BA (Visual Arts) from Stellenbosch University in 2017. In 2018, Burger showed in Masan, South Korea as part of the Rhizome Artist Residency. She was selected to take part in the 2019 ICA Live Art Workshop, receiving training from art experts all around the world. In 2019 Burger opened her first solo exhibition of paintings titled, Painted Mantras, at GUS Gallery and facilitated a group collaboration project titled, Take Flight, selected to be part of Infecting the City Live Art Festival. At the moment, Nicolene is completing a practice-based master’s degree in Theatre and Performance at the University of Cape Town.

In 2020, Nicolene created a series of ZOOM performances with Lumkile Mzayiya called, Evoked?. These performances led her to create exclusive performances from her home in 2021 to accommodate the mid-pandemic audience. She also started focusing more on the sustainability of creative practices in the last 3 years and now offers creative coaching sessions to artists of all kinds. By sharing what she has learned from a 10-year practice, Burger hopes to relay more directly the sense of vulnerability with which she makes art and the core belief to her practice: Art is an immensely important and powerful bridge of communication that can offer understanding, healing and connection.

Nicolene writes our blog posts on art history with an emphasis on renowned artists and contemporary art. She also writes in the field of art industry. Her extensive artistic background and her studies in Fine and Studio Arts contribute to her expertise in the field.

Learn more about Nicolene Burger and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Nicolene, Burger, “What Paintings Are in the Louvre? – Exploring the Best Louvre Artworks.” Art in Context. May 16, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/what-paintings-are-in-the-louvre/

Burger, N. (2022, 16 May). What Paintings Are in the Louvre? – Exploring the Best Louvre Artworks. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/what-paintings-are-in-the-louvre/

Burger, Nicolene. “What Paintings Are in the Louvre? – Exploring the Best Louvre Artworks.” Art in Context, May 16, 2022. https://artincontext.org/what-paintings-are-in-the-louvre/.