St Mark’s Basilica – Exploring the Basilica di San Marco in Venice

Why is St Mark’s Basilica famous? The Basilica di san Marco in Venice played an important role in the city’s political and religious spheres. But, when was St Mark’s Basilica built and who built St Mark’s Basilica? Let us find out the answers to these questions and more in this article about the history and architecture of St Mark’s Basilica.

The Basilica Di San Marco in Venice

| Architect | Domenico I Contarini (d. 1071) |

| Date Completed | 1094 |

| Function | Cathedral |

| Location | Venice, Italy |

| Architectural Style | Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic |

This iconic cathedral in Venice was originally built to function as the Doge’s private chapel. However, over the centuries it has taken up a significantly more important role in the social and spiritual life of the people of Venice. It houses the relics of St Mark which were taken from Alexandria in Egypt, and the Basilica di san Marco is now world famous for its exquisite mosaic art.

History of St Mark’s Basilica

Several sources from the Middle Ages all tell the tale of two Venetian traders transporting Saint Mark’s remains from Egypt to Venice. They further claim that the remains of Saint Mark were originally housed in a corner turret of the Doge’s palace.

In his testament, Giustiniano Participazio instructed that his widow and his heir, Giovanni, build a cathedral devoted to Saint Mark, where the remains would subsequently be enshrined.

The First Church Period

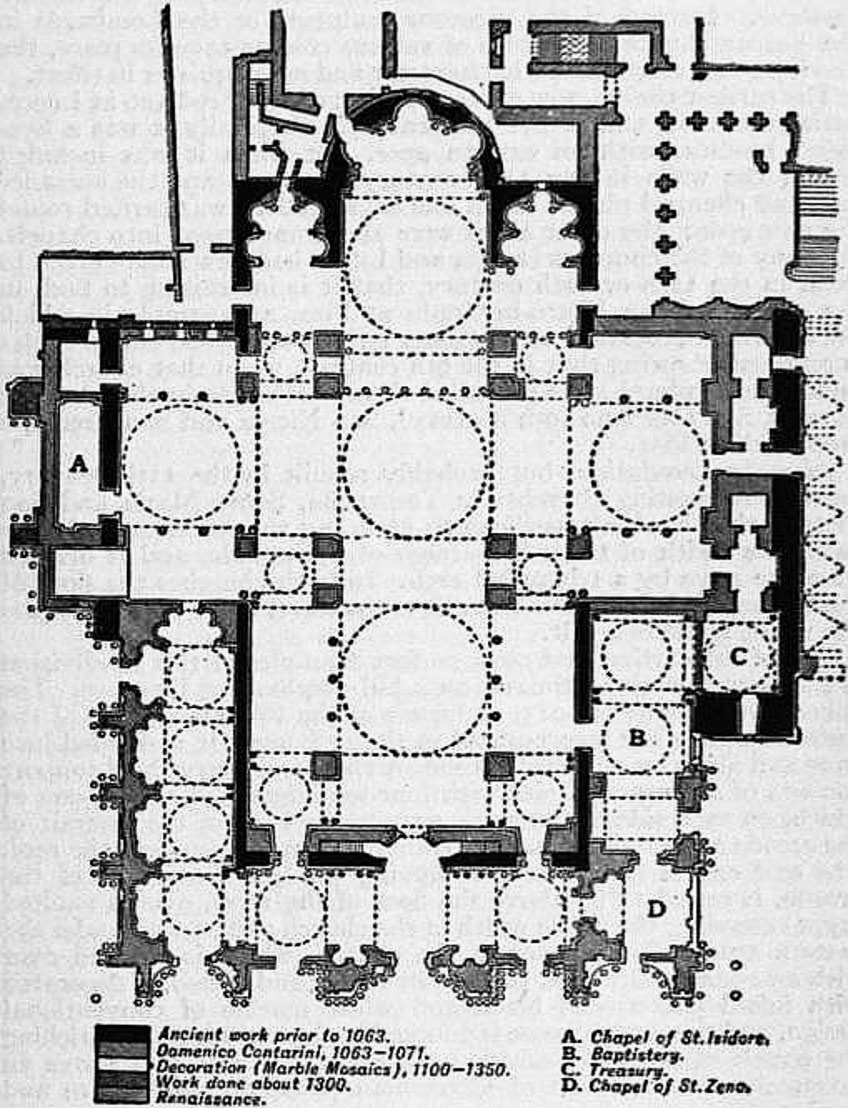

Even though the original building was long thought to be rectangular in shape, excavations have revealed that St Mark’s Basilica was always a cruciform structure with a central dome, most likely made of wood. This substantial departure from the traditional architectural style of a rectangular design in favor of a centralized Byzantine layout represented Venetian traders’ rising economic presence in the capital as well as the region’s political connections with Byzantium.

The foundations and lower portions of many of the main walls are thought to be the only remaining components of the original church. The large entry doorway and the western section of the vault under the main dome, which seems to have functioned as the platform for a raised podium upon which the original altar was situated, may also date from the early church.

The Orseolo Church Period

During the populist revolt against the Doge in 976 AD, an enraged crowd started a fire to remove the Doge from the castrum and it spread all the way to the nearby church, heavily damaging it. Although the building was not entirely razed, the general assembly had to make alternative arrangements for a venue to host the election of Pietro I Orseolo as the next Doge, and the ceremony was moved to the cathedral of San Pietro di Castello.

After only two years, the building was completely restored entirely at the cost of the Orseolo family, indicating that the actual damage was minor.

The wooden components had been incinerated, but the supports and walls remained mostly intact. The actual appearance of the Orseolo church after restoration is unknown, but considering the brief time of the renovation, it is likely that efforts were focused on repairing the damage with little room for creativity or innovations.

The Contarini Church Period

A sense of community drove several Italian towns in the mid-11th century to initiate the development or repair of great churches. Venice was likewise eager to exhibit its expanding economic power and influence, and St Mark’s was extensively rebuilt and expanded under Contarini in 1063 AD, to the degree that the completed building looked entirely different. The domes, in particular, were very different, as they were originally made from wood but had been replaced with brick.

Renovation of the church’s inside started with Salvo, who gathered beautiful marbles for the church’s ornamentation and personally funded the mosaic design, employing a skilled mosaicist from Constantinople.

Both the facade and interiors of the cathedral were afterward coated in marble and precious stones and adorned with reliefs, columns, and sculptures. Many of these decorative features were salvaged from old or Byzantine structures. During the Latin Empire, Venetians raided Constantinople’s palaces, churches, and public landmarks, stealing stones and columns.

The Architecture of St Mark’s Basilica

The western facade of St. Mark’s Basilica is split into three main sections: the lower and upper sections, and the domes. Five arched entrances in the lower level are surrounded by painted marble columns and extend into the entrance hall through huge bronze doors. The top level is covered with mosaics representing Christ’s life, and the golden tiled mural known as The Last Judgment is located above the main portal.

The side entrance lunettes are illustrated with tales about St Mark’s relics. The national symbol of the Venetian Republic, the Winged Lion, is featured above the huge central window.

The ornamentation of the church’s southern entrance hall was redone in the 13th century in correlation with renovations in the adjacent hallway, although little is known about the entrance hall’s original look. The current mosaic sequence in the nave serves as a prologue to the mosaic sequence on the building’s facade, which tells the story of Saint Mark’s relics being transported from Egypt to Venice.

The divine prediction that St Mark would one day be laid in Venice is represented, confirming Venice’s rightful claim to acquire the relics. The images depicting the composition of Saint Mark’s Gospel, which is afterward given to Saint Peter, are meant to establish his authority.

The journey of Saint Mark to Egypt and his miraculous feats there are also given special relevance, creating continuity with the initial tableau on the facade, which depicts the transportation of the remains from Egypt.

Inside the Basilica di San Marco

The gold backdrop, with limited light, not only produces an impression that grabs the observers’ senses but is also adorned with a rich iconography of Christian artwork. The basilica is designed in the shape of a Greek cross, with each arm split into three naves. The mosaics, together with the cathedral’s design, represent the Byzantine style, despite the interior’s mix of architectural influences ranging from the classical period to the 19th century.

The five domes, which rise at the intersections and above the arms of the Greek cross, are over 13 meters in circumference and have 16 windows in each dome.

The domes’ interiors are decorated with gold mosaics dating from 1160 to 1200. The center dome portrays Christ’s ascent into heaven after his resurrection. Although Western influences have impacted the dome’s iconography, the primary one is still clearly Byzantine.

Transept Chapels are frequently devoted to a certain saint. There are several chapels devoted to the Madonna and various icons in St. Mark’s Basilica. They may be found in the smaller arms along either side of the principal dome. The Cappella di San Giovanni, above the northern transept, features 12th-century mosaics representing St. John’s life. The Byzantine image of the Madonna Nicopeia is featured on the altar in Cappella Della Madonna Nicopeia, which is also located on the northern transept. The Cappella di San Clemente, also referred to as the Doge’s Chapel, is located in the southern transept.

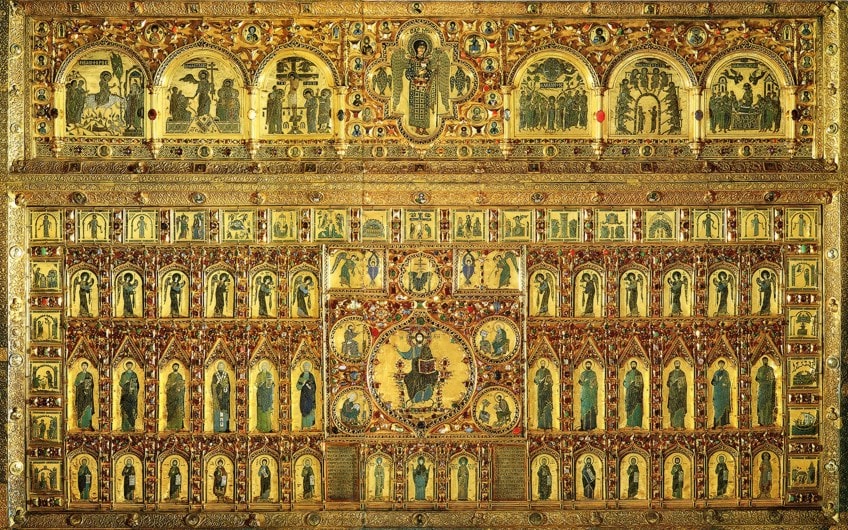

Pala d’Oro is the most prized of the basilica’s possessions. This Byzantine altarpiece is a gold panel set with hundreds of stones, including thousands of emeralds, pearls, sapphires, amethysts, garnets, topazes, and rubies.

The devious Napoleon seized a few in 1797, but lessons were learned, and these rare jewels are now protected by protective glass. This altar was created by skilled artisans from Constantinople and Venice. The basilica’s treasury, which houses riches acquired over the years – 280 items in silver, gold, glass, and other valuable materials to be exact – is located to the side of the main altar and may be entered from the south transept.

Venice was inundated with valuable marble from Constantinople following the Fourth Crusade in 1204. When erecting the basilica, these stones were employed in a representational manner depending on their qualities and color. For instance, crimson porphyry was regarded as the most valuable stone and was connected with royal and godly authority. As a result, it was employed for the Tetrarchs’ porphyry group on the south facade and the inside of the Doge’s tribune. The pavonazzetto marble was another expensive stone that was utilized in the apse columns.

When a new structure was constructed in 1063, the remnants of prior structures were turned into a crypt, and the new basilica was erected above it.

This crypt contains St. Mark’s grave. The vault reopened in 1889, following the renovation of the basilica. The grave of the great prophet, located under the presbytery, was recently the subject of debate when a British scholar claimed that it contained the bones of Alexander the Great. However, additional data is still needed to support this view.

The Mosaic Interior of St Mark’s Basilica

Although St Mark’s design was influenced by the Church of the Holy Apostles, it had to be modified due to ceremonial restrictions and limits imposed by the pre-existing foundations and walls. The earliest mosaics of St Mark’s Basilica, which are placed in the entry porch niches in the entrance hall, may date back to 1070. Although Byzantine in design, they are quite outdated in comparison to contemporaneous Byzantine styles. They were most likely produced by mosaicists who left Constantinople in the mid-11th century to concentrate on Torcello’s church and thereafter settled in the region.

The figures in the central apse, which were completed in the late 11th and early 12th centuries, are more current but still archaic in design.

The 12th century was the most significant era of the church’s decoration when Venice’s ties with Byzantium fluctuated between moments of political turmoil and peace. During the periods of unrest, artistic influences from the East were restricted and during periods of peace, trade continued and this benefited the Venetians by enabling interactions that provided them with a better understanding of eastern designs. The arrival of Byzantine materials and artisans further developed their knowledge of Eastern techniques.

The figures in Immanuel’s dome are from the first quarter of the century and are the product of extremely proficient mosaicists who were most likely Greek-trained. They illustrate the enhanced classicism and naturalism of Constantinople’s middle-Byzantine art, as well as the local traditions of rougher and broken lines.

Byzantine miniatures were reproduced more or less precisely for the mosaics in subsequent phases of construction in the transept and choir chapels.

However, any eastern influences that may represent the newest artistic advancements in Constantinople are hard to discern. The Dome of Pentecost, completed somewhere in the first part of the 12th century, demonstrates a direct knowledge of artistic advances in Constantinople.

A substantial amount of the mosaics in Immanuel Dome, as well as the majority of the Dome of the Ascension and numerous vaults in the western cross-arm, had to be entirely restored in the latter third of the 12th century as a result of a catastrophic event, the origin, and date of which are unknown.

The regional style is evident; however, the more dynamic stances, ruffled drapery, emotion, and enhanced contrast demonstrate Constantinople’s partial incorporation of the emerging dramatic style.

The Dome of the Ascension’s mosaics, as well as those showing the Passion in an adjacent vault, symbolize the development of the Venetian mosaic tradition and are considered one of the great triumphs of Medieval art.

Starting in the 13th century, once the galleries were dismantled, the mosaic ornamentation was expanded to the lower walls. The first mosaic, portraying the Agony in the Garden, displays a blend of western and eastern traditions. The complex designs of the late Komnenian era are still visible. However, the statuesque aspect of the figures, which are also more curved, reflects contemporaneous innovations in Byzantine art, such as those found at Studenica Monastery. Similarly, a refinement associated with western Gothic emerges and combines with Byzantine characteristics.

Later mosaics of the time with geometric backgrounds inspired by stained-glass panels in French cathedrals show more Gothic influences.

Interesting Facts About St Mark’s Basilica

As we have learned, the Basilica di san Marco in Venice has played an important role in Venetian life through the ages. It also contains some of the most beautiful mosaic artwork that still draws visitors to gaze at its splendor. Now, let’s take a look at some other interesting facts about St Mark’s Basilica.

Venetian traders Stole the Remains of St Mark

The traders managed to sneak them past the Muslim guards by concealing them in a barrel between layers of pork – quite a sneaky move considering that Muslims do not like to deal with or touch pork. Then while traveling back to Venice a massive storm almost prematurely ended their return voyage. According to legends, the apparition of St. Mark appeared to the crew, telling them to lower the vessel’s sails.

They made it back safely thanks to the divine visitation of the saint, and the entire story can be seen on a mosaic from the 13th century above the basilica’s left entrance.

There Are Tides in the Venetian Lagoon

Occasionally these tides are bigger than usual, flooding areas of the city. Because St. Mark’s Square is the lowest point throughout the city, its floor is sometimes partly or completely flooded with water. But on the 12th of November, 2019, the tide climbed to the second highest elevation ever documented in the city’s history.

The church’s caretakers were not prepared for this incident: the water not only filled the antechamber but also the basilica itself.

The Damage Was Significant

The structure is still being restored. At the very least, this terrible catastrophe sped up the installation of the system of portable barriers designed to defend the Lagoon from the most destructive tides. When you enter the church’s museum, you will notice four bronze horses. The sculptures are old and were taken from Constantinople and transported to Venice as war trophies.

This is only one of several treasures captured from Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade.

Because the Terrain in Venice Is Fragile, Large Structures Cannot Be Built

Instead, compact, light, and flexible materials must be utilized. But the Venetians wanted to leave an impression on their visitors, so they devised some really ingenious tactics to fool the eye and give everyone the appearance that the structures are massive and intimidating. The basilica managed to achieve this with great effect, as the five large domes that give St. Mark’s Basilica its unique form are actually only a superstructure built of wood covered with a thin covering of lead.

They are totally empty: the domes with all the mosaics visible within the church are significantly lower than those you see from the outside.

The Mosaics in the Basilica Cover More Than 8,000 Square Meters

This is equivalent to one-and-a-half football fields. They were not all done at once though, in fact, they were created over a period of around 800 years, and the majority of them were made in gold. This means that the mosaics appear slightly different depending on what time of day they are viewed, as the light entering the building changes the colors of the murals.

St Mark’s Basilica has a long and detailed history that stretches back into time, offering modern observers an opportunity to take in over 800 years of beautiful mosaic art and architecture. It reflects the influences of the Byzantine culture and indeed there were many artisans who had left Constantinople for various jobs in Venice and had remained there, after which they worked on subsequent projects such as the basilica. The Basilica di san Marco is not only a beautiful representation of Venetian architecture but displays the influence of those who worked on it from the east beautifully.

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was St Mark’s Basilica Built?

It was originally built in 829. However, it has been rebuilt and extended throughout the years. It was first known as the Participazio church, but not much is left of it except some of the church’s foundations and a few walls. After angry protesters tried to drive out the Doge, the church was badly damaged and had to be rebuilt. It took around two years and was funded by the Orseolo family. The basilica was then further developed in 1063 when it was known as the Contarini church.

Who Built St Mark’s Basilica?

The first person to be involved in the design of the church was Domenico I Contarini. He was Venice’s 30th Doge. Layers of marble had to be brought in from the Middle East for the construction of the basilica. The version of the basilica that we can observe today is a combination of styles and influences that have all combined to create a unique and cosmopolitan architectural style that utilizes practices and designs from both the west and east. The layout is influenced by the Greek cross design, while other influences come from Byzantium culture.

Why Is St Mark’s Basilica Famous?

There are several reasons that the Basilica di san Marco in Venice is so famous. One of the reasons is the story attached to the building of the church. It was built to house the remains of a saint who had been snuck out of Egypt in a barrel full of pork and taken to Venice by a couple of Venetian traders. While on their return journey, the ship and its occupants were nearly capsized by heavy storms. The ghost of the saint was said to have appeared to them and told them to lower the ship’s sails. They did so and returned safely to Venice. The church was then built and the story of that miraculous story can be seen on a fresco in the basilica. This is another reason it is so famous – all the incredible mosaics inside which were created by various artisans over a period of eight centuries! That means that depending on where you look, you can see art from a different century all in one building. And to top it off, these mosaics are gilded with gold, which means that depending on how light falls on the mosaics, a whole new range of colors can be seen, totally transforming the images.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “St Mark’s Basilica – Exploring the Basilica di San Marco in Venice.” Art in Context. September 13, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/st-marks-basilica/

van Huyssteen, J. (2022, 13 September). St Mark’s Basilica – Exploring the Basilica di San Marco in Venice. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/st-marks-basilica/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “St Mark’s Basilica – Exploring the Basilica di San Marco in Venice.” Art in Context, September 13, 2022. https://artincontext.org/st-marks-basilica/.