Crystal Palace Building in London – The Crystal Palace History

The Crystal Palace building in London was originally located in Hyde Park and was built to house the Great Exhibition. The Crystal Palace’s history does not end with the exhibition though, and the Crystal Palace building would eventually be relocated. Who designed the Crystal Palace and what happened to the Crystal Palace? Join us as we answer those questions by exploring the Crystal Palace’s architecture, history, and significance.

Exploring the History of the Crystal Palace Building in London

| Architect | Joseph Paxton (1803 – 1865) |

| Date of Construction | 1851 |

| Date of Destruction | 30 November 1936 |

| Cause of Destruction | Fire |

| Materials | Cast iron and plate glass |

| Function | Exhibition palace |

| Location | Hyde Park (original location); Sydenham Hill (relocation, now destroyed) |

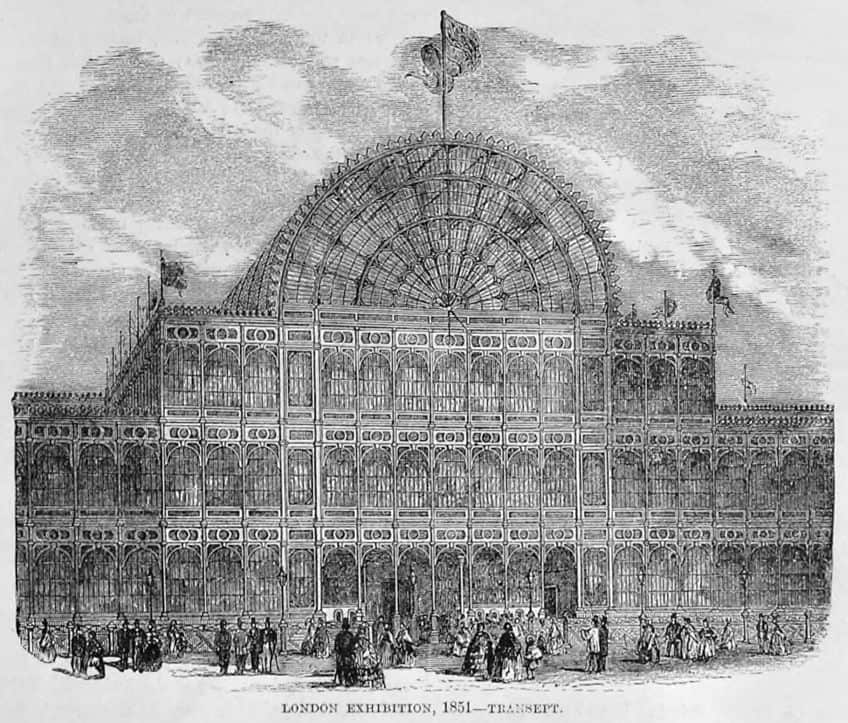

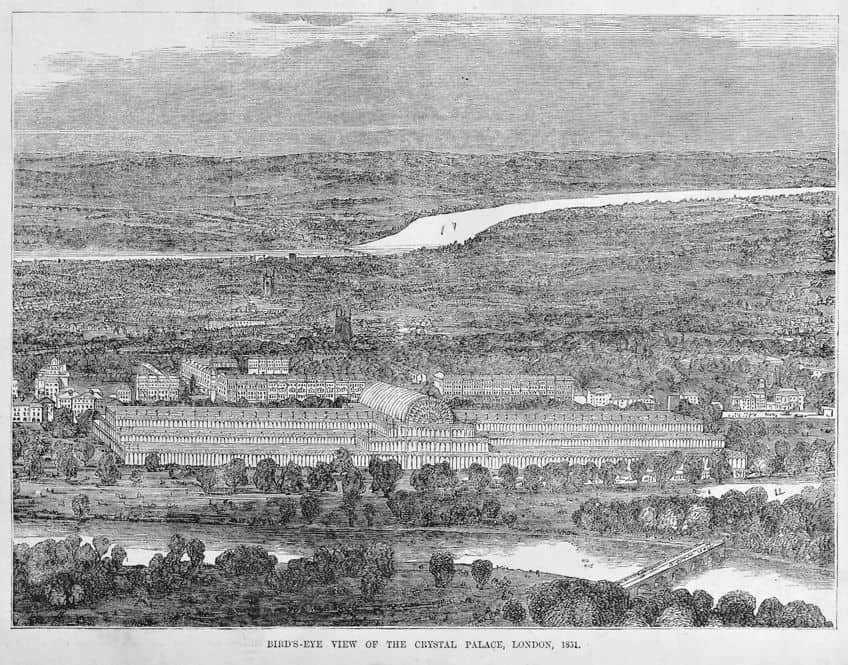

The Crystal Palace building in London was regarded as one of the most inspiring buildings of its era. From its original location in Hyde Park to its eventual destruction, the Crystal Palace’s architecture and design drew thousands of guests. At the time of its construction, it was the largest building in the world!

The Crystal Palace’s History

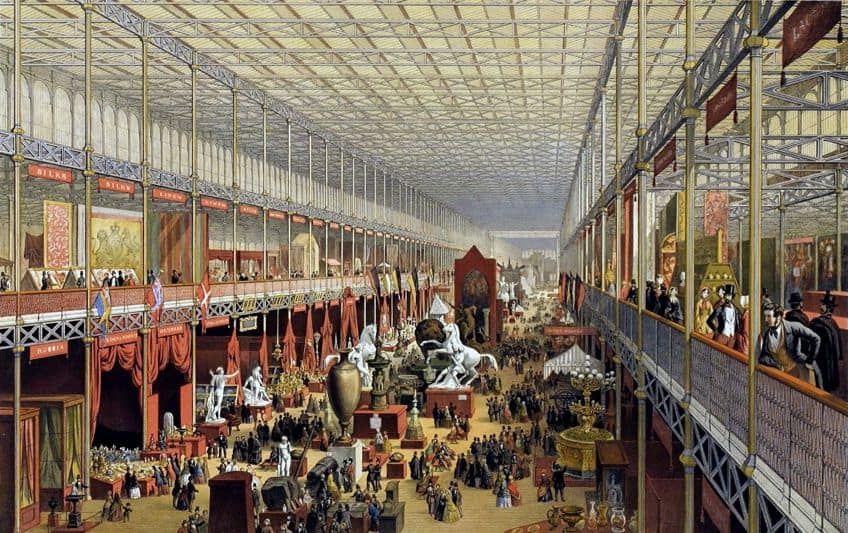

The Crystal Palace was originally constructed to house the approximately 14,000 exhibitors from around the globe who showcased at the Great Exhibition in 1851. But, what was the Great Exhibition, and what was showcased there? Let’s discover more about the Crystal Palace’s history by starting with the exhibition itself.

The Great Exhibition of 1851

This international exhibition took place from the 1st of May to the 15th of October in 1851. It was held to showcase the various new technologies that had begun to emerge during the Industrial Revolution. It was also the first of many world fairs that grew in popularity in the 19th century that focused on industry and culture. It was organized by a British engineer and civil servant named Henry Cole and Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert. In attendance at the exhibition were many renowned names such as Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, Charles Dickens, Samuel Colt, and Michael Faraday.

The exhibition’s admission rates fluctuated depending on the day, with ticket prices reduced as the legislative season ended and the more wealthy individuals began to leave London.

To entice potential working-class consumers, newly developing railways provided heavily discounted tickets for those coming from remote regions, and special rates were made available to groups, usually headed by the local vicar. The event’s official catalog included exhibitors not just from the United Kingdom, but also from its “Colonies and 44 Foreign States”. The Great Exhibition drew six million visitors, or almost one-third of the British population at the time, with an average daily attendance of around 42,830 people!

The Crystal Palace’s Original Location

The commission responsible for organizing the exhibition was formed in January 1850, and it was agreed upon from the start that the entire undertaking would be financed by public subscription. An executive development committee was established to take charge of the planning and building of the Crystal Palace building. By the 15th of March 1850, they were set to receive submissions that had to meet multiple key criteria: the structure had to be temporary, simple in design, inexpensive, and practical to construct in the brief period of time left before the exhibition’s opening on the 1st of May 1851.

The exhibition committee received more than 240 entries in the span of three weeks, including 38 foreign contributions from the Netherlands, Australia, Hanover, Belgium, Brunswick, Switzerland, Hamburg, and France. Despite the large number of applications, the committee ended up rejecting all of them. To make matters worse for the committee, the location of the exhibition had yet to be determined. The desired location was in Hyde Park, but other options were Battersea Park, Wormwood Scrubs, Victoria Park, the Isle of Dogs, and Regent’s Park. However, it was eventually decided that Hyde Park would be the ideal location for the Crystal Palace building.

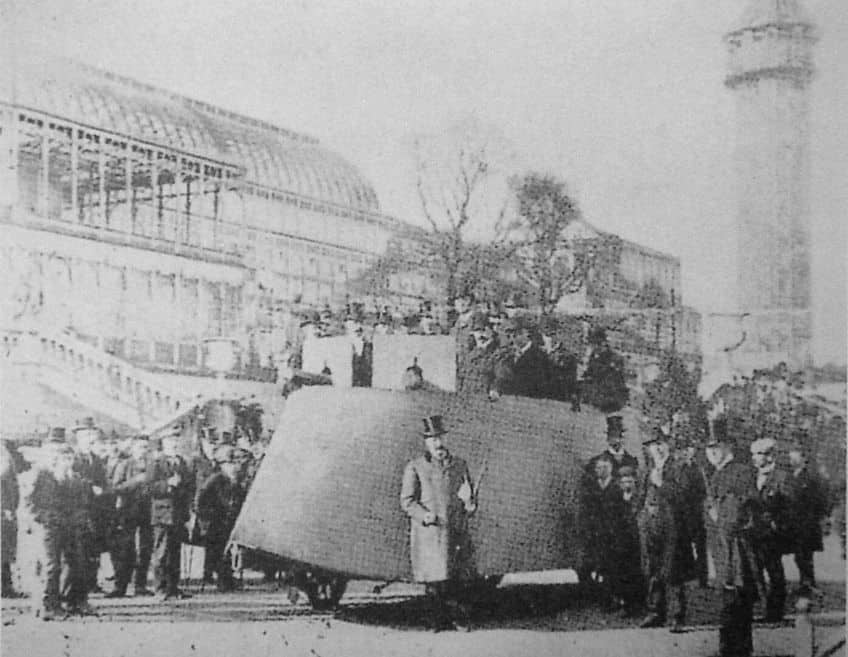

Relocation to Sydenham Hill

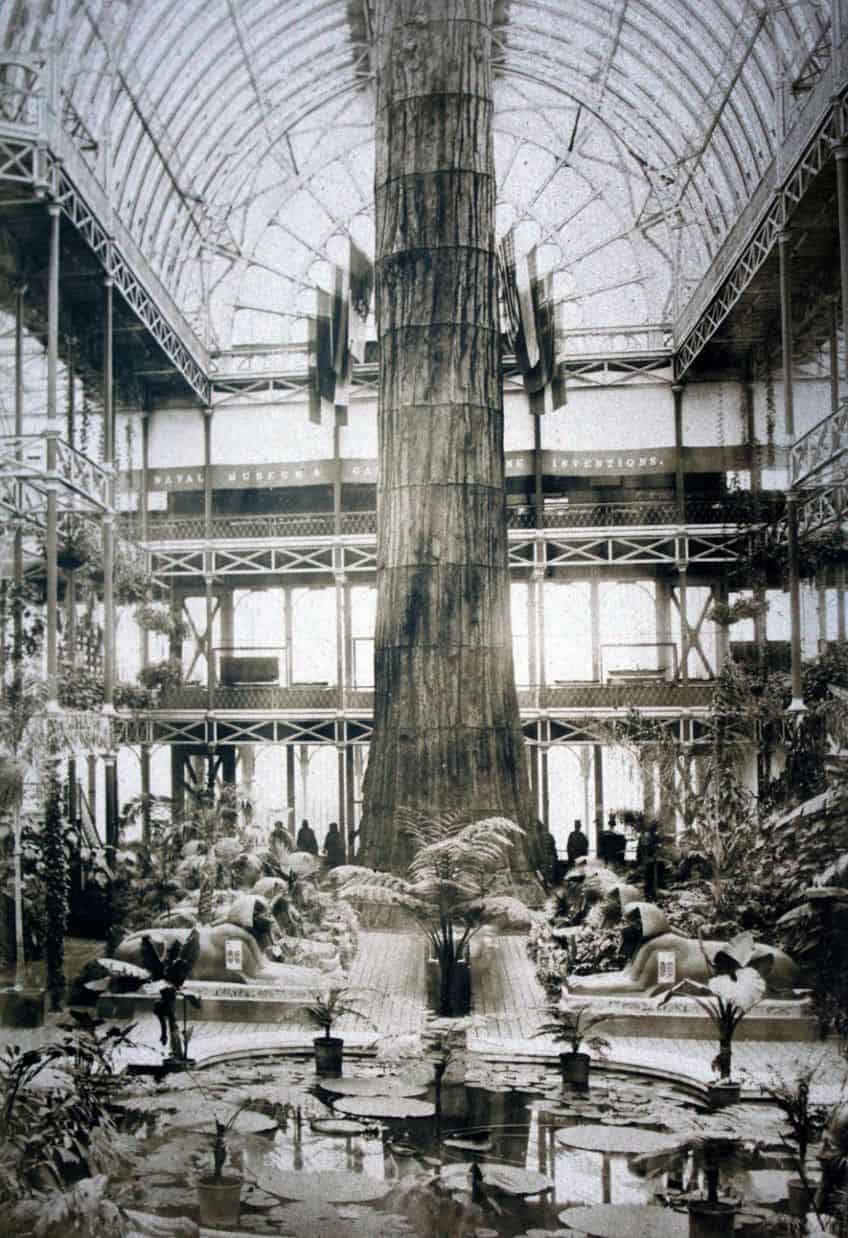

The Great Exhibition had a six-month lifespan, after which a decision on the future of the Crystal Palace building had to be made. A group of eight businessmen established a holding company and recommended that the structure be dismantled and moved to Penge Place, by Sydenham Hill. The reconstruction process started in 1852. While integrating most of the original Hyde Park building’s structural components, the building’s new design was so dissimilar that it was regarded as a distinct structure – a ‘Beaux-arts’ design in metal and glass.

The main gallery was remodeled and given a barrel-vaulted roof; the center transept was substantially enlarged and raised; and the main entrance’s massive arch was surrounded by a new facade and connected by an imposing system of stairways and terraces.

The structure was elevated many meters above the surrounding grounds, unlike the Hyde Park design, and two massive transepts were built at either end of the main gallery. Within two years, the restored edifice was finished, and on the 10th of June, 1854, Queen Victoria took part in the official opening ceremony in front of 40,000 spectators.

Decline of the Building

The decision to move to Sydenham left the company with a debt that it never paid off. This was largely due to the Palace’s incapacity to accommodate Sunday visitors in its earliest years: plenty of individuals were employed every day except for Sundays when it was closed for business. The Lord’s Day Observance Society argued that workers should not be pushed to work at the Palace on Sundays and that if they wished to go, their bosses should offer them days off during the week. By 1860, it was open on Sundays, and 40,000 visits were reported on one Sunday in May 1861. By the 1890s, the Palace’s appeal and condition of maintenance had declined; the addition of kiosks and booths had transformed it into a much more low-key attraction.

The edifice fell into decay in the years after the Festival of Empire, as the massive debt and maintenance expenditures proved insurmountable, and bankruptcy was declared in 1911. The Earl of Plymouth purchased it to rescue it from developers, with the agreement that he would be reimbursed by a fund established by the Lord Mayor of London. In 1913, the mayor reported that £90,000 was still needed in addition to the funds previously raised by the local authorities. The Times newspaper made an appeal, and the money had been raised in 13 days; an unnamed donor gave £30,000.

Camberwell Borough Council declined to pay, while Penge Urban District Council cut their original contribution from £20,000 to a meager $5,000.

The Earl of Plymouth made up the difference, paying £30,000 less than he had previously. A board of trustees was established in the 1920s under the direction of manager Sir Henry Buckland. He is reputed to have been an imposing but fair individual who had an enormous love for the Crystal Palace and quickly began renovating it. The renovation brought back tourists, and the Palace began to generate a tiny profit again. Buckland and his team also worked to improve the water features and gardens, including Brocks’ Thursday evening fireworks shows.

The Destruction of the Crystal Palace

On the evening of the 30th of November, 1936, two building staff discovered a small office fire caused by an explosion in the women’s cloakroom and tried to put it out. When they realized how out of control it was getting, they called the Penge fire department. However, despite the arrival of 89 fire engines and nearly 400 firefighters, they were still not able to put out the fire. The entire Crystal Palace building had been razed within hours, and the light of the flames could be seen throughout eight counties.

Due to the dry old timber flooring and the large number of combustible goods in the structure, the fire spread rapidly, fueled by the strong winds that night. It is believed that around 100,000 individuals flocked to Sydenham Hill to observe the fire, including Winston Churchill, who apparently commented that it was “the end of an era”. Much of the Crystal Palace’s lower floor had been utilized for John Logie Baird’s mechanical television experiments, and a great deal of his work was destroyed by the fire. Baird believed that the fire was a planned plot against the work he did on television development, however, the real cause of the fire remains unknown.

Crystal Palace’s Architecture and Design

When the committee could not find a suitable submission for the building’s design, they decided to try and design it themselves, but it received much criticism. At this stage, famed gardener Joseph Paxton started to show interest and decided to present his own design, with the enthusiastic support of Henry Cole. By 1850, Paxton had established himself as a leading figure in British horticulture, as well as a well-known freelance landscape designer. He’d done a lot of research on glasshouse building, coming up with a lot of new ways for modular construction employing laminated wood, standard-size glass sheets, and prefabricated cast iron.

John Paxton’s Vision

Paxton felt enthusiastic after his meeting with Cole on the 9th of June, 1850. He instantly headed to Hyde Park and wandered about the proposed exhibition site. He doodled his original idea onto a sheet of pink paper two days later, on the 11th of June, while he was at a Midland Railway board meeting. This preliminary drawing had all of the main characteristics of the final structure, and it is evidence of Paxton’s creative thinking and hard work that the necessary comprehensive planning, calculations, and expenses were submitted in under two weeks. It was a risky gamble for Paxton, but the odds were in his favor: he had an excellent track record as a builder and garden designer, he was sure that his concept met the brief, and the building’s commission was a tight deadline to select a design and have it constructed in time for the exhibition’s opening in under a year.

In the end, Paxton’s design met and exceeded all of the standards, and it proved to be far faster and less expensive to construct than any other type of structure of comparable scale.

The Construction of the Crystal Palace

Stakes were first hammered into the ground to loosely mark out the places for the cast iron columns, which were then carefully positioned using theodolite measurements. Concrete was then poured for the foundations, and the supporting plates for the columns were installed. The modules were then quickly assembled after the foundations were laid. Before erection, connector brackets were fastened to the tops of the columns and lifted into position.

The construction took place before the invention of motorized cranes; the columns had to be raised manually using a basic crane mechanism called a shear leg. When finished, the Crystal Palace provided an unparalleled exhibition space as it was basically a self-supporting shell perched on narrow iron columns with no interior structural barriers. Because it was nearly entirely made of glass, it required no artificial source of lighting during the day, lowering the exhibition’s operating expenses. Paxton’s success was recognized internationally, and he was knighted by Queen Victoria in honor of his contributions.

Paxton’s Use of Glass and Iron

Paxton required a structure that was large enough to hold the exhibits and spectacular enough to serve as an appropriate location for the exhibition. The most significant structures of the period were built using masonry, which was expensive and heavy. Paxton realized that utilizing iron and glass would result in a much lighter and less expensive construction that would also be durable and solid.

Because of the use of glass, natural light was able to fill the interior of the building, providing a light and airy area for the displays.

This was especially critical for the Great Exhibition because many of the exhibits featured things that required strong illumination to be properly appreciated. Iron was utilized for the building’s structural support. Paxton was able to design a structure that was both sturdy and flexible by employing iron columns and beams. The iron enabled the structure to be built fast and efficiently, which was critical given the exhibition’s short deadline.

The Building’s Influence on Architecture

Before the construction of Crystal Palace, buildings were mostly made of heavy masonry, but Paxton’s design illustrated the ability of glass and iron to produce huge, open spaces. The Crystal Palace served as a highly visible and widely acclaimed edifice that influenced a number of other architects to follow comparable design principles. This resulted in an increase in the number of glass and iron constructions in the late 19th and early 20th century, notably in exhibition halls, train stations, and other public buildings.

The integration of glass and iron in architectural design had various benefits, including more natural light, better ventilation, and being able to construct big, open areas without the need for massive internal support columns. The Crystal Palace also had an impact on the contemporary skyscraper’s evolution, as architects started experimenting with new materials and construction processes that allowed for larger and more efficient structures. The application of steel and reinforced concrete in building construction, for instance, may be traced back to Paxton and others’ innovations.

The Significance of the Great Exhibition

One of the most significant effects of the Great Exhibition was its display of technical and industrial advances of the day. These displays featured a diverse range of tools, machinery, and goods from across the world, which aided in the advancement of innovation and the emergence of new technology. It also contributed to the participant countries’ feeling of international competitiveness and cooperation. Many examples of creative product design were also included in the exhibitions, which served to determine the direction of design in the future years.

The show was a huge commercial success, attracting over six million people over the period of several months.

As businesses tried to take advantage of the opportunities created by the exhibition, this served to increase international commerce and encourage economic growth. The Great Exhibition also had a cultural influence, both in the United Kingdom and across the globe. It contributed to a feeling of national identity, as well as an appreciation of global community and collaboration. The show received extensive newspaper coverage and became a cultural milestone, influencing art, literature, and music in the years that followed.

The Exhibitions Role in Promoting Advancement

The Great Exhibition was created with the goal of promoting global industrial and technological breakthroughs. The displays were organized by country inside the Crystal Palace building, with every country presenting its unique technical and industrial capabilities. Printing presses, steam engines, textiles, and ceramics were among the displays, which comprised a diverse assortment of machines and tools from across the globe. The displays were meticulously chosen to highlight the best of what the various nations had to offer the world, and they served to stimulate international competition and collaboration in the field of technological innovation.

The Great Exhibition also included a variety of lectures, demonstrations, and other activities intended to encourage the interchange of ideas and the spreading of information. This contributed to the participants becoming a community and helped to establish an atmosphere of innovation and cooperation that stretched well beyond the bounds of the show. The creative architecture and stunning grandeur of the Crystal Palace building in London established a very suitable setting for the exhibition, as well as inspired a generation of designers and entrepreneurs who would go on to influence the course of history.

The Legacy of the Crystal Palace Building

The two water towers and a part of the northern end of the main nave that was too heavily damaged to preserve were all that remained standing after the fire. The right southern tower was demolished immediately after the fire because the damage had compromised its stability and posed a significant risk to surrounding homes. In 1941, the northern tower was dismantled using explosives. Its removal was not explained, however, it was rumored that it was done in order to remove a potential landmark for German planes during WWII. In reality, though, German bombers followed the Thames on their route to London.

After the Palace was destroyed, the High-Level Branch station fell into disuse and was ultimately closed in 1954.

Following the war, the land was put to use for a variety of purposes. The Crystal Palace motor racing track opened in the park between 1927 and 1972, but the noise was very unpopular with people living close by, and racing hours were restricted by a high court order. In the mid-1950s, the Crystal Palace transmission station was erected on the former site of the aquarium and is today one of London’s principal television transmission masts.

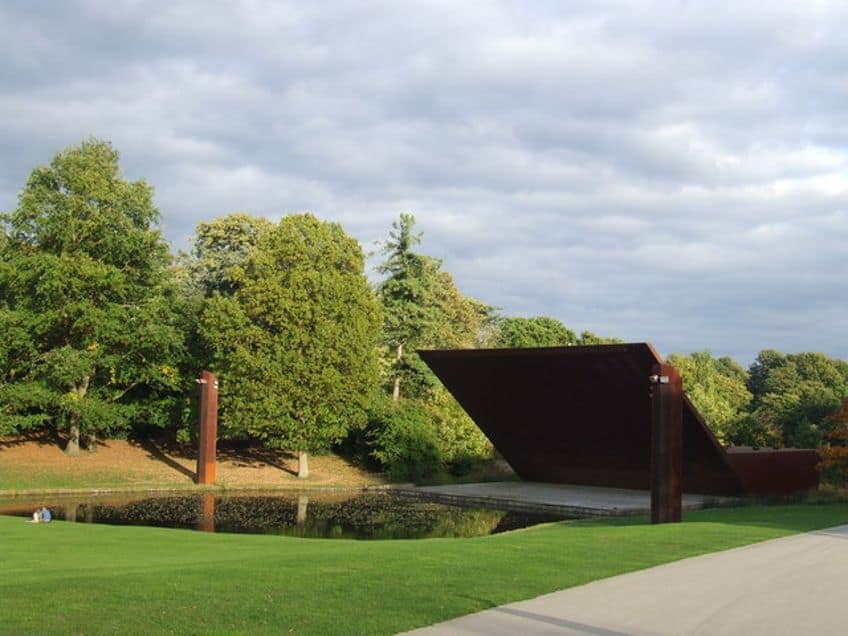

The Crystal Palace Bowl, a natural amphitheater in the park’s northern corner, has hosted open-air concerts in the summer since the 1960s. Classical and symphonic music, as well as pop, rock, reggae, and blues, have all been performed. During its height, the Bowl hosted Bob Marley, Pink Floyd, Eric Clapton, Elton John, and The Beach Boys. Ian Ritchie constructed an award-winning permanent framework for the stage, which was renovated in 1997. It has been inactive as an entertainment venue for several years now, and its stage has deteriorated, but the London Borough of Bromley Council is collaborating with a regional action group to discover innovative and community-minded business ideas to bring back the beloved concert platform.

Proposals for the Site

Numerous plans for the old location of the Palace have fallen through the cracks throughout the years. After a public inquiry in December 2010, the London Development Agency granted permission to invest £67.5 million to rehabilitate the property, comprising new dwellings and a regional sports center. Before clearance became public, the LDA backed out of managing the park and paying for it. In 2013, the Chinese business ZhongRong Holdings carried out preliminary discussions with the London Borough of Bromley about rebuilding the Crystal Palace building on the park’s northern side.

Yet, when the developer’s 16-month exclusivity agreement with the council to complete its plans ended in February 2015, it was terminated.

The Influence of the Crystal Palace Building on Popular Culture

The Crystal Palace was instrumental in defining the 19th-century cultural environment, stimulating creativity and invention in the visual arts, literature, and popular entertainment. Its influence may still be felt today, both in surviving instances of glass and iron buildings in addition to the Great Exhibition’s own legacy. Few other constructions have ever managed to grab the public’s imagination in the same manner as the Crystal Palace building in London did. It was an incredible feat in engineering and design.

The Crystal Palace had an instant impact on popular culture in the field of architecture. Architects were inspired by the structure’s creative use of glass and iron and began experimenting with new materials, which resulted in the widespread application of glass and iron in construction. These buildings became representations of advancement and modernity, and they influenced the development of the urban environment in the following decades. The Crystal Palace had a great influence on the visual arts as well. Its magnificent proportions and delicate curves were considerably praised, inspiring designers and artists to develop a variety of works with similar elements.

Some artists even produced paintings of the palace itself, such as Camille Pissarro’s The Crystal Palace, which was produced in 1971.

The Crystal Palace has served as a dramatic background for a number of notable creative events, including modern art and photography exhibits. The exhibition was also influential in shaping the development of popular entertainment in the area. Several musical and theatrical acts were presented throughout the exhibition, and these events helped promote the Crystal Palace as a popular location for entertainment.

Significance in Literature

Dickens recounted visiting Crystal Palace Park in his unique creative style of writing in an essay published on the 3rd of December, 1853, with one wonderful passage clearly illustrating visiting Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’ studio, where all the statues were being created. In Russian literature of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Crystal Palace was also utilized as a symbol of development and utopian rationalism. Because of its creative architecture and technical advances, the building became a strong symbol of modernity, capturing the minds of authors and philosophers interested in probing the potential of industry, science, and social transformation.

Probably one of the most noteworthy uses of the Crystal Palace in Russian literature is in Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s novel What Is to Be Done? published in 1863. The tale follows Vera, a young lady who is committed to advancing the goal of change in society and politics. The Crystal Palace serves as a metaphor for Vera’s ideal society, one in which technological advances and science are employed to eradicate poverty, sickness, and social inequity. The glass walls and iron structure of the building represent the transparency and logic of this utopian society, which has been imagined as a paradigm for the future.

Another instance of the Crystal Palace’s impact on Russian literature may be found in the writings of Fyodor Dostoevsky.

In his novel The Idiot, (1869), the fictional character of Prince Myshkin is depicted as being stunned by the majesty and mechanical complexity of the Crystal Palace in London. Myshkin sees the Crystal Palace as the peak of human achievement, and he is excited by the potential of technology and science to change the world.

The Crystal Palace Site Today

The Crystal Palace site is still a significant cultural and recreational destination in London, drawing people from all over to enjoy its museums, parks, and other attractions. Today, the Crystal Palace site is mostly a neighborhood park called Crystal Palace Park. It features a variety of leisure amenities such as playgrounds, sports fields, and a maze. The park also has an array of attractions and monuments commemorating the Crystal Palace’s past, including the original fountains and terraces, the famed sphinxes, and a collection of sculptures and statues.

The park also houses a variety of cultural organizations, including the Crystal Palace Park Farm and the Crystal Palace Museum, in addition to recreational amenities. The museum includes a collection of relics and memorabilia relating to the Crystal Palace’s past, while the farm allows visitors to engage with farm animals while learning about animal husbandry and agriculture.

That concludes this article on the Crystal Palace building in London. Originally designed and constructed to house the 1851 Great Exhibition, it was a temporary site for the building, which was subsequently moved to Sydenham Hill. There, it was the sire of many more exhibitions, plays, and other forms of entertainment until it eventually fell into repair. Despite efforts to fix up the building, it was eventually ravaged by a fire in 1936. However, the site is still home to several institutions today and has had a significant impact on society.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Crystal Palace Building in London?

The original Crystal Palace was built in Hyde Park. This was only meant to be a temporary site, though, and it was then moved to Sydenham Hill. After being relocated to Sydenham Hill, the Crystal Palace remained a famous tourist and cultural attraction for many years. To accommodate the increased number of tourists, the structure was enlarged and restored, with additional wings and amenities added. The Crystal Palace continued to host a diverse range of exhibitions, events, and performances during its time at Sydenham Hill. It was also the scene of significant scientific and technical breakthroughs. A terrible fire engulfed the Crystal Palace in 1936, destroying the structure and most of its contents. It was witnessed by thousands of people and regarded as the end of an era.

Who Designed the Crystal Palace?

Joseph Paxton, an English landscaper, designed the Crystal Palace building. Paxton’s Crystal Palace architecture was well-lauded for its creative use of materials and graceful simplicity. The Crystal Palace building in London eventually became a symbol of Victorian architecture, and it helped to establish a new standard for exhibition space construction and design in the country and abroad. Paxton’s success with the Crystal Palace further contributed to his reputation as a renowned architect.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Crystal Palace Building in London – The Crystal Palace History.” Art in Context. May 25, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/crystal-palace-building-in-london/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 25 May). Crystal Palace Building in London – The Crystal Palace History. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/crystal-palace-building-in-london/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Crystal Palace Building in London – The Crystal Palace History.” Art in Context, May 25, 2023. https://artincontext.org/crystal-palace-building-in-london/.