Royal Family Art Collection – The British Royal Collection of Art

Since the beginning of the British monarchy, the Royal family’s art collection has grown to house a multitude of precious art objects and artworks from prestigious artists. Since the passing of Queen Elizabeth II on September 08, 2022, the world has drawn its attention to multiple points of concern over the history of the British monarchy and particularly its acquisition of precious objects via colonial means. This article will introduce you to some of the finest artworks housed in the royal family’s art collection while also examining a few objects of interest and their acquisition.

Table of Contents

- 1 The British Royal Collection Trust

- 2 Treasures of the Royal Collection

- 2.1 Royal Family Paintings

- 2.1.1 Triptych: Crucifixion and other Scenes (c. 1302 – 1308) by Duccio Di Buoninsegna

- 2.1.2 Queen Isabella I of Spain, Queen of Castille (c. 1470 – 1520) by the Spanish School

- 2.1.3 Boy Peeling Fruit (c. 1592 – 1593) by Michelangelo

- 2.1.4 A Rabbi with a Cap (1635) by Rembrandt van Rijn

- 2.1.5 The Five Eldest Children of Charles I (1637) by Anthony van Dyck

- 2.2 Royal Drawings

- 2.2.1 A Man Wearing a Turban and a Cloak (1510) by Leonardo da Vinci

- 2.2.2 The Miraculous Draft of Fishes (1515 – 1516) by Raphael Sanzio da Urbino

- 2.2.3 Sir John Godsalve (1532 – 1534) by Hans Holbein the Younger

- 2.2.4 “Sword, Axe, and Gold Mask Captured in the Ashanti Expedition” (c. Unknown) by William Gibb

- 2.3 Precious Objects From the Royal Collection

- 2.1 Royal Family Paintings

- 3 Accessibility

- 4 Frequently Asked Questions

The British Royal Collection Trust

Recognized as the world’s largest private art collection, the British Royal Collection Trust is a department of the Royal household, which is dedicated to the maintenance of the Royal Collection, including its acquisitions, exhibitions, and conservation services. The trust was established in 1993 and encompasses its trading company, Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd., and a registered charity. The main household, Buckingham Palace in England, alongside other residences of the monarchy contain “treasures” such as paintings, family portraits, photographs, sculptures, furniture, and objects, which are also part of the Royal Collection.

The vast collection comprises multiple private art collections from various members of the Royal family, including Italian art, art objects from Asia, gifts from various countries, the famous Crown Jewels, jade objects from around the world, artwork from the High Renaissance, diamonds, tapestries, and many other art forms.

The works found in the collection are considered highly valuable and of great historical importance. The manner of acquisition concerning some of the objects in the collection has been debated considering the history of British conquest and its relationship to Colonialism as executed over the British Empire’s colonies in Caribbean, African, and Asian sites. Below, we will take a look at some of the most popular treasures of the royal family’s art collection, including some of the finest royal family paintings and drawings.

Treasures of the Royal Collection

The Royal Collection is distributed across 13 sites and is currently under the ownership of King Charles III, overseen by the Royal Collection Trust. It is important to understand that the Royal Collection consists of items that were acquired under the Crown and from private collections of members of the royal family. The collection consists of more than one million objects, over 150,000 paper works, over 30,000 drawings and watercolor artworks, and more than 7,000 paintings.

Approximately 3,000 objects are loaned to art museums around the world and others fall under temporary loans for public exhibitions.

Royal Family Paintings

Members of the royal family who contributed greatly to the expansion of the Royal Collection included Charles I, Charles II, George III, George IV, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg, and the late Queen Elizabeth II. Below, we will look at a few royal family paintings that may spark your interest.

Triptych: Crucifixion and other Scenes (c. 1302 – 1308) by Duccio Di Buoninsegna

| Artist | Duccio Di Buoninsegna (1278 – 1319) |

| Date | c. 1302 – 1308 |

| Medium | Tempera on panel |

| Dimensions (cm) | 44.9 x 31.4 |

The oldest painting in the collection is by Duccio di Buoninsegna, who was a Sienese artist most famous for his work, Maestà, executed for the Siena Cathedral in 1311. The triptych above showcases scenes from the crucifixion of Jesus Christ surrounded by other biblical scenes meant to be read in a specific order.

The triptych begins with the “Annunciation and the Virgin and Child Enthroned” on the left. As a continuation of “Virgin and Child Enthroned”, the right-hand side showcases the “Stigmatization of Saint Francis”, who was considered to be the second Christ. The Virgin Mary appears four times in the triptych.

The painting was reconstructed as a triptych in 1988 as part of conservation efforts and it was only discovered then that the artist had implemented corrective perspective measures to right the distortion that came with the angle of the wings. In the paintings’ acquisition history, it is noted that in 1846, the painting was thought to have been created by Fra Angelico. It was likely that the painting was commissioned by Prince Albert (1819-1861).

Queen Isabella I of Spain, Queen of Castille (c. 1470 – 1520) by the Spanish School

| Artist | Spanish school |

| Date | c. 1470 – 1520 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions (cm) | 37.5 x 26.9 x 0.5 |

Painted as a duo, this portrait of Queen Isabella I of Castille pairs with the portrait of her partner, Ferdinand II of Aragon and appeared to arrive at the Royal Collection as of 1542 under the reign of Henry VIII. The marriage of Queen Isabella I with her cousin Ferdinand II also brought along immense success in the endeavors of territorial expansion and the couple also funded the travels of Christopher Columbus in 1492, followed by the “discovery” of the Americas. The painting shows Isabella I adorned in a gold dress with a white head cap and a gold necklace with a pearl and ruby pendant. She is also seen holding a small book containing religious text, which was common for signifying the piety of a woman.

The artist behind the painting is unclear and there is speculation as to its origin being Flemish.

Another interesting fact surrounding the painting is that it was acquired under the rule of King Henry VIII, who was both revered and scorned. Henry VIII was made famous for holding a total of six marriages, including the beheading of his second wife Anne Boleyn, and his significant contributions to the expansion of royal power during his rule.

During his reign, he also led the establishment of the English Reformation and executed many people who seemed to fall out of his favor. In his later years, he was also described as “tyrannical”, with eight years of unrest between England and Scotland and the French invasions.

Henry VIII is also credited with being one of the founders of the Royal Navy.

A year prior to the painting being documented in the inventory of the Royal Collection in 1542, English laws, social norms, and customs began their descent onto the native people of Ireland. In 1541, the Irish Parliament released an act that declared the Kingdom of Ireland as a “perpetual appendage” to the English Crown.

Boy Peeling Fruit (c. 1592 – 1593) by Michelangelo

| Artist | Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571 – 1610) |

| Date | c. 1592 – 1593 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 63 x 53 |

Believed to be the original work of famous Italian painter Caravaggio, Boy Peeling Fruit (c. 1592-1593) is said to be the earliest surviving work of Caravaggio. The composition of a boy peeling a fruit is also believed to be one of several other paintings by Caravaggio that circulated during the 17th century.

The painting was probably acquired by Charles II and was first recorded in 1688 by Caravaggio’s Christian name, Michael Angelo as “a piece, being a boy in his shirt, paring fruit”.

Charles II left no legitimate children for succession but bore many illegitimate children, who he acknowledged, to his many mistresses. The public, who was under Charles II’s rule, “resented paying taxes”, which were spent on his children and mistresses, who also received titles. The former Princess of Wales, Diana, was a descendant of Charles II’s illegitimate children and her son, presently the Duke of Cornwall is now heir to the British throne.

A Rabbi with a Cap (1635) by Rembrandt van Rijn

| Artist | Rembrandt van Rijn |

| Date | 1635 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions (cm) | 72.6 x 62.3 |

A lesser-known portrait by Rembrandt van Rijn, A Rabbi with a Cap (1635) was first acquired by George III around 1762 under the Joseph Smith collection of the British Consul. The painting was allegedly (previously) acquired from a painter by the name of Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini. What makes this painting special is that it was executed on a rare hardwood called Cordia, which can only be found in the tropical areas of America.

The wood was previously part of a door and later became the painting’s support. The date marked on the painting was also suggestive that it is possibly the first (or earliest) date at which that specific species of wood entered Europe. The Royal Collection consists of many other paintings by the old master.

George III was the “longest reigning king” in the history of Britain. He was first the King of Great Britain from 1760 until 1801 and lastly, the King of the UK and Ireland until 1820. Around the 1750s, George III issued a document that denounced arguments centered around the promotion of slavery and the transatlantic slave trade.

According to Andrew Roberts, a historian, George III thought of slavery as “absurd” and “ridiculous” and that he never partook in the purchase of slaves. During the American War of Independence (1775-1783), in November of 1775, Lord Dunmore (John Murray) issued a statement freeing slaves from their rebel masters.

Lord Dunmore was appointed by George III and his proclamation resulted in some of the slaves escaping from their “masters” and joining the British military.

Some of the slaves who fought were also given certificates of freedom in 1783. From 1781 until 1800, approximately (perhaps more) 400,000 people from Africa were shipped off as slaves to America from British ports. It was only in 1807 that George III implemented a new law, which banned the transatlantic slave trade activities from the British Empire. Prior to this, the “nefarious trade” (a reference to the slave trade activities), was initiated by Sir John Hawkins (a Naval Commander) who was backed up by Elizabeth I (1558-1603) in 1573.

The Five Eldest Children of Charles I (1637) by Anthony van Dyck

| Artist | Anthony van Dyck (1599 – 1641) |

| Date | 1637 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 163.2 x 198.8 |

Charles I reigned as the King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1625 to 1649 and was known to be a huge fan of collecting art. He was also a patron of the famous Flemish Baroque artist, Sir Anthony van Dyck and collected many Italian paintings. At some point after his execution, Charles I’s art collection had to be sold off but after the monarchy regained its traction in 1660, Charles II managed to restore and replenish the collection.

This painting by Anthony van Dyck is currently located in the Queen’s Gallery at Windsor Castle and captures the young royal children of Charles I.

The Five Eldest Children of Charles I by Anthony van Dyck fell out of the hands of the Royal Collection while under James II and the Commonwealth. George III repurchased the painting in 1765 and was stationed at the Buckingham house by 1774.

The power behind the painting lies in the contrast of the innocent children with their position and status.

Other incredible paintings contained in the Royal Collection include Judith with the head of Holofernes (1613) by Cristofano Allori, Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman (c. 1662-1665) by Johannes Vermeer, and Portrait of Agatha Bas (1641) by Rembrandt van Rijn.

Royal Drawings

There are many artworks in the Royal Collection to unpack and examine in light of their surrounding provenance and socio-political context. Now we will take a look at some of the most interesting royal drawings found in the Royal Collection.

A Man Wearing a Turban and a Cloak (1510) by Leonardo da Vinci

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) |

| Date | 1510 |

| Medium | Red chalk, gone over with black chalk on pale red prepared paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 21.2 x 13.8 |

An avid collector of the brilliant polymath’s preparatory sketches and drawings, A Man Wearing a Turban and a Cloak (1510) by Leonardo da Vinci is said to have been acquired by Charles II around the late 17th century. The drawing illustrates a man positioned three-quarters to the left side with his head, which is tilted to the right, facing the viewer. The highlight of the drawing is the man’s turban and his cloak, which he holds with his arms folded.

The drawing was first passed on to Francesco Melzi, another Italian painter and student of da Vinci. The drawing then made its way to Charles II via the 14th Earl of Arundel.

The Miraculous Draft of Fishes (1515 – 1516) by Raphael Sanzio da Urbino

| Artist | Raphael Sanzio da Urbino (1483 – 1520) |

| Date | 1515 – 1516 |

| Medium | Bodycolor over charcoal on sheets of paper, mounted on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 319 x 399 |

This large-scale drawing by the most famous Italian painter and architect, Raphael da Urbino was created as a cartoon for the tapestry, which came later on. This preparatory draft royal drawing was commissioned by Pope Leo X for use in the Sistine Chapel and illustrates two boats; one filled with fish and seated in it, Jesus Christ and his apostles Peter and Andrew. The other boat is occupied by two fishermen captured in action; one man hauling the fishing net while the other man steers the boat. A flock of birds can be seen in the foreground and in the distance, one can observe the shore with buildings and crowds.

The drawing is said to have been acquired by Charles I in 1623 and it has been loaned out to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London since 1865.

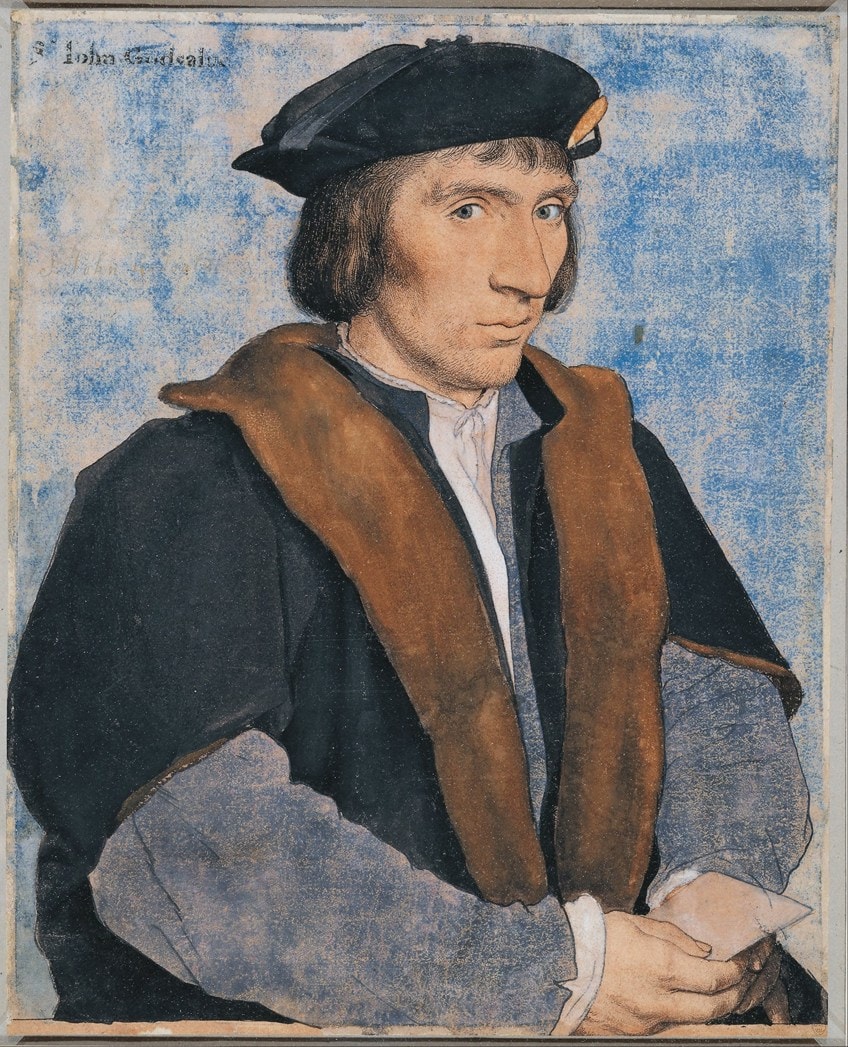

Sir John Godsalve (1532 – 1534) by Hans Holbein the Younger

| Artist | Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8 – 1543) |

| Date | 1532 – 1534 |

| Medium | Black and red chalk, pen, ink, bodycolor, and white heightening on pale pink prepared paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 36.2 x 29.2 |

Charles I was the first great collector of art in the Royal family and part of his collection included drawings of Henry VIII’s court created by the German-Swiss artist, Hans Holbein the Younger. Holbein the Younger specialized in the Northern Renaissance style and was also an exceptional printmaker. This portrait by Holbein the Younger is said to have remained in his studio until his death and was supposedly never given to the original sitter. The figure seated in the drawing depicts Sir John Godsalve, who was an English politician, seated donning a fur-collared black gown over a blue-sleeved shirt as he holds a letter.

It is believed that the artist and sitter were already well acquainted and Godsalve had commissioned him for a portrait.

The drawing is said to be problematic in nature since it is the only drawing by Holbein the Younger at Windsor that is executed in full color and was perhaps a pastel intended for a panel, serving the same function as that for a painting. A similar painting made by another artist exists at the Philadelphia Museum of Art but it seems as though both the works are independent of each other.

“Sword, Axe, and Gold Mask Captured in the Ashanti Expedition” (c. Unknown) by William Gibb

| Artist | William Gibb (1839 – 1929) |

| Date | c. Unknown |

| Medium | Watercolor/drawing; possibly lithograph |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unavailable |

Classified under the Royal Collection’s subdivision of watercolors and drawings, this artwork of unknown establishment was initially presented to Queen Mary around 1935 and depicts different objects of the Ashanti King. In the drawing, one observes a triangular-shaped piece of iron, a royal ax, a wooden-handled sword, a gold mask, and a box resting on a case of solid gold. It is unclear as to the method or process behind the making of the work, but the artist, William Gibb, was known to be a famous Scottish illustrator and landscape artist.

The context that this artwork may be associated with follows the history of the Anglo-Ashanti wars documented as a series of wars that occurred between 1824 and 1900.

The wars waged were between the Ashanti Empire, who were stationed in a British Crown colony and what is known in the present day as Ghana (the Gold Coast) and Ivory Coast, and the British Empire alongside African allies. The Ashanti and British Empires clashed a total of five times with the British Empire winning the last two major battles. Local people of the coast relied on the British Empire for protection from the control desired by the Ashanti.

Precious Objects From the Royal Collection

The Royal Collection boasts 52 sub-divisions under their objects category in their collection, listing multiple historical objects from weapons and armor to books, ceramics, crown jewels, sculptures, and textiles. Below, we have compiled a few interesting objects under the Royal Collection for your observation.

The Oba Bronze Head (c. 1650) From the Kingdom of Benin

| Artist | Unknown |

| Origin | Kingdom of Benin |

| Medium | Bronze, copper-tin alloys |

| Dimensions (cm) | 30 x 24 x 24 |

Housed at the Grand Vestibule of Windsor Castle, this bronze and iron Benin sculpture of an Oba head (head of a King) was the subject of controversy surrounding its origin and potential restitution. The sculpture was created to represent the individual character and fate of the king. The sculpture was also commonly placed on shrines as an acknowledgment of the leadership qualities of the preceding King.

The sculpture was originally presented as a gift to the late Elizabeth II (1926-2022) by the Head of the Federal Military government of Nigeria, General Yakubu Gowon upon his state visit to the UK in 1973.

The controversy surrounding the acquisition of the sculpture follows its provenance, which began during the 1897 British Punitive Expedition where the bronze head was first seized. The sculpture was stolen and carried back to Britain where it found its way back into the art market. Somewhere along the line, the Nigerian National Museum acquired the sculpture between 1946 and 1957, and the sculpture was returned home, that is until it was gifted to Elizabeth II in 1973.

In 2021, the return of the “twice-looted” Benin head was the subject of debate and according to an article by The Art Newspaper, a spokesperson of the Royal Collection commented on the questions around the sculpture’s restitution stating that the matter was “for discussion by the trustees of the Royal Collection Trust”.

The Edo Museum of West African Art is scheduled to open in 2025 and with the influx of other prestigious European art institutions returning objects from their Benin collections on either loan or restitution, there has been no comment on the Royal Collection’s intentions.

According to reports on the appearance of the Benin head in the Royal Collection after 1973, the head had been kept among other “curios” at Windsor Castle and was first exhibited at Buckingham Palace in 2002 as part of an exhibition showcasing the various gifts to the Queen (Elizabeth II). According to the display, the head was labeled as a “modern replica” but upon inspection, it appeared to be older and of real quality. A specialist in the field of West-African art evaluated the sculpture and deemed it to be the original.

Further insights into the last transfer of the sculpture to the Royal family’s art collection in 1973 were found. According to the investigation, the Nigerian General had called the Nigerian National Museum director, Ekpo Eyo, and stated that he needed a gift for Elizabeth II for the sake of a gift and to express his gratitude to the monarch for the support of the UK during the Biafra civil war (1967-1970). The director received instruction to open the museum to the General so he could select a piece for his trip.

It has been speculated that the Royal Collection or members affiliated with receiving the gifts had known that the sculpture was not a replica but was instead an original with its previous history of being seized from Nigeria and lacking an antiquities license.

In August of 2022, the Horniman Museum in London announced that it plans to return approximately 72 artifacts, including the Benin bronze objects, which were originally looted from Benin City in 1897 and distributed across over 150 institutions around the world.

Delhi Durbar Necklace and Cullinan VII Pendant (c. 1911)

| Origin | Pretoria, South Africa |

| Medium | Diamonds, emeralds, platinum, gold |

| Dimensions (cm) | 46 |

Holding an 8.8-carat diamond cut from the original largest diamond in the world, the Cullinan diamond, this Delhi Durbar necklace is an iconic and contested object of the Royal Collection. The piece was initially created for Queen Mary and formed part of a suite of jewelry pieces for the 1911 Delhi Durbar. The famous necklace has been the subject of recent inquiry as to the return of the Cullinan diamond back to its point of origin. Also called The great star of Africa, the Cullinan diamond is currently worth between $400 million and $2 billion.

The claim goes that the diamond was handed to the British as a token of friendship and peace but the circumstances surrounding this event include the Apartheid era in South Africa, which was far from a period of peace for the people of color in the country.

The Royal family had reportedly cut the diamond into several pieces and installed the largest piece in a scepter. The star of Africa is currently still at the Tower of London, where other royal precious objects and gems lie. Vuyo Zungula, an MP of the African Transformation Movement (ATM) had recently demanded the return of the Cullinan diamond following the passing of Queen Elizabeth II stating that South Africa should exit the Commonwealth and demand reparations for all the harm done by Britain, in addition to drafting a new constitution that would be founded on the will of the people of the country and not the British Magna Carta”. The MP also demanded the “return of all the gold and diamonds stolen by Britain”.

Among other objects that have come into the spotlight following the monarch’s death include a ring from Tipu Sultan allegedly taken off the body of the Sultan in 1799.

Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother’s Crown (1937): The Koh-i-Noor Diamond

| Origin | India |

| Medium | Platinum, diamonds, rock crystal, velvet, ermine |

| Dimensions (cm) | 20.7 |

Embellished with only 2800 diamonds on the platinum frame of the crown, this famous headpiece made for Queen Elizabeth in 1937 is also noted for containing the Koh-i-Noor (Koh-i-Nûr) diamond, which has also been a subject of reflection concerning the diamond’s history. Having been mounted on previous crowns, the Koh-i-Noor diamond was also worn by Elizabeth at the coronation of her daughter, Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

The source of the main attraction, the Koh-i-Noor diamond originated in India in the alluvial mines dating back thousands of years ago.

The diamond was also noted in Hindu beliefs as a precious gem that was even admired by the God Krishna, despite its rumored attachment to a curse. Prior to becoming an embellishment on a British crown, the diamond circulated in India, and according to William Dalrymple and Anita Anand, both historians, the diamond was sieved out of river sand and since then has been “perfectly scripted” and comparable to the famous fictional series Game of Thrones.

For many centuries, the world’s source of diamonds and other precious minerals was India. The issue that the diamond brings up is the question of how such items affiliated with colonial history and looting should be dealt with. Should the diamond be returned? If so, what does this mean for the preservation of the diamond? How does one begin to organize reparations for an object that has been claimed by India, Pakistan, and even Afghanistan?

According to the book, Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond (2016) authored by two historians, in ancient India, jewelry was the primary form of representation for members of the hierarchy who would adorn themselves with precious jewels to signify their status. Many other highly complex systems were also discovered for the categorization of other precious gems.

The Koh-i-Noor diamond came into the possession of a Turco-Mongol leader called Zahir-ud-din Babur, who also invaded India in 1526 and was allegedly obsessed with gemstones.

The Mughals held authority over India for approximately 330 years and expanded their territory across Eastern Afghanistan, present-day India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, all while pillaging the land for gemstones. The Mughal leader Shah Jahan sent out a commission for a gem-embellished throne to be made in 1628 and drew artistic inspiration from the mythical throne of King Solomon who also featured in the religious texts found in Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. The throne took around several years to finish and was extremely costly to build. Amidst the many precious stones that adorned the throne was the Timur Ruby and the Koh-i-Noor diamond.

The diamond was seated at the very top of the throne in the head of a peacock but the ruby was appreciated a lot more for its rich color, which was a preference for the Mughals. Copious amounts of attention flowed towards the Mughals and the peacock throne, which also caught the attention of Nader Shah, who was a Persian ruler. Nader commenced his invasion of Delhi in 1739 and the result of the invasion was the high cost of thousands of civilian lives along with a depleted treasury.

Nader looted the land and the ruby and the Koh-i-Noor diamond became part of his new jewelry set of an armband.

The Koh-i-Noor diamond left India and found its dwelling in Afghanistan for around 70 years and was passed through many rulers accompanied by much bloodshed and looting. The British then got involved through the massive conflicts that ensued between the factions in Central Asia and by the 19th century, the British East India Company (BEIC) had grown its territory into coastal cities and the interior of India. The British were successful in territory expansion and amassed a talent for claiming ownership over other lands’ natural resources.

The diamond then fell into the possession of the Sikh leader, Ranjit Singh around 1813 and by then the gem had become an object associated with power and leadership.

Strangely, one can say that the allure of the diamond was elevated during this time and became a symbol that had to be owned, and whoever was in possession of the diamond, was also in possession of power, authority, and prestige. As you can imagine, this must have been quite the quest for the British and can be seen as a symbol of greed and reinforcement of colonial superiority.

Upon the death of the Sikh ruler, the diamond was to be given to a group of Hindu priests but the British had kept a record of this and the press reacted to this in such a way that it seemed ridiculous. An anonymous editorial described the matter as “the most costly gem in the known world was committed to the trust of profane…priesthood”. The writer encouraged the BEIC to track the gem so “that it might be theirs”. After a series of tumultuous conflicts and rulers after Ranjit Singh, a legal paper was signed in 1849, which amended the Treaty of Lahore and stipulated that the young Duleep Singh (who was the only heir left and only 10 years of age) would relinquish not only all claims on his sovereignty, but also the Koh-i-Noor diamond.

From there on out, the diamond was in the possession of Queen Victoria and claimed to be a gift from Sultan Abdul Medjid for the British’ support during the Crimean war.

Among other precious objects housed in the British Royal Collection are a few artifacts from the Saqqara pyramids, Chinese porcelain vases from the Jiangxi province, a gold crown of the Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah II, a Persian tiara presented to Queen Victoria in 1838, and the Delhi Durbar necklace with a pendant cut from the Cullinan diamond, which originally came from South Africa.

Accessibility

To visit the different exhibits from the collection, a fee is charged for entrance, which is said to go directly to the Royal Collection Trust. For free admissions throughout the year, a one-year membership is also offered to the public but it is not guaranteed that visitors will see more than one exhibition per year as the exhibitions occur on a seasonal basis. Many public art galleries became free of charge in the UK in 2001 but the Royal Collection Trust is established as a charity and, therefore, relies on the entrance fees.

The collection described itself as a private collection that is “held in trust by the Crown, previously Elizabeth II, who also owned a few pieces, including the inherited artworks left by the Queen’s mother.

The costs of maintenance are upheld by taxpayers’ funds, that is, the general public. The matter of access, according to the Royal Collection Trust, states that their aim is to ensure that the public has as much access as possible. Just last year, Buckingham Palace offered a rate of £60 per adult for entry between July and October but was compared to the Royal Collection exhibition available in Madrid for only 12 Euros. The current event, which is assumed to have been placed on hold, was scheduled for September 15, 2022, and was the Platinum Jubilee: The Queen’s Accession, costing an adult £30.

While the collection houses many artifacts, objects, paintings, and historical artworks, there are still questions around the objects derived from the British’ colonial history, which leave more room for speculation on restitutions. What is your opinion on the Royal Collection? A tweet by Anushay Hossain beckons, “Can India get back the Koh-i-Noor diamond/everything in the British Museum that was stolen?”

Frequently Asked Questions

What Can Be Found in the Royal Collection?

Many artworks and over one million historical objects, drawings, paintings, sculptures, textiles, and archaeological artifacts can be found in the Royal Collection. The works are all spread across 13 sites in the UK.

How Many Jewels Are in the Royal Collection?

There are more than 100 precious objects in the Royal Collection and it consists of 23 thousand gemstones with the most famous crown, the Imperial State Crown (1937) containing 2868 diamonds, 269 pearls, 17 sapphires, 11 emeralds, and four rubies alone.

How Many Leonardo da Vinci Artworks Exist in the Royal Collection?

The Royal Collection houses an estimated 563 artworks created by Leonardo da Vinci and is part of the largest collection of da Vinci artworks in the world.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Royal Family Art Collection – The British Royal Collection of Art.” Art in Context. September 19, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/royal-family-art-collection/

Meyer, I. (2022, 19 September). Royal Family Art Collection – The British Royal Collection of Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/royal-family-art-collection/

Meyer, Isabella. “Royal Family Art Collection – The British Royal Collection of Art.” Art in Context, September 19, 2022. https://artincontext.org/royal-family-art-collection/.