Lincoln Cathedral – The History of the Famous Cathedral

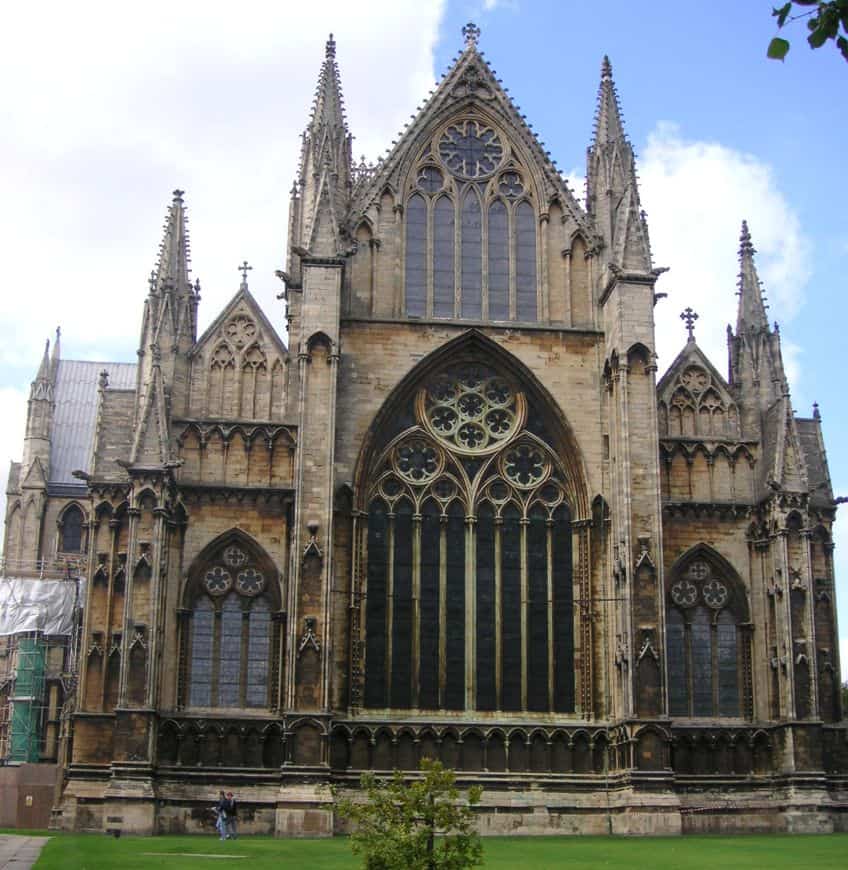

Of all the Lincolnshire cathedrals, the Lincoln Cathedral is likely the most well-known in the region. Construction on the cathedral began in 1072 and was completed in stages throughout the period known as the High Middle Ages. It was erected in the Early Gothic style, as were many of England’s medieval cathedrals. When the central spire of Lincoln Cathedral was completed in 1311, it became the world’s tallest structure.

Table of Contents

The History and Architecture of the Lincoln Cathedral

| Date Completed | 1311 |

| Architect | Remigius de Fécamp (died 1092) |

| Function | Cathedral |

| Height (meters) | 160 |

| Location | Lincoln, Lincolnshire, England |

When the central spire of Lincoln Cathedral was completed in 1311, it became the world’s highest building and was the first structure to maintain that distinction since the Great Pyramid of Giza. It kept that title for 238 years, that is until the spire unfortunately fell in 1548 and was never rebuilt. If the spire had remained standing, it would have still been regarded as the world’s tallest building until the erection of the Washington Monument in 1884. For 100s of years, the cathedral housed one of the four intact copies of the Magna Carta, which is presently safely housed at Lincoln Castle.

The History of the Lincoln Cathedral

The first Bishop of Lincoln, Remigius de Fécamp, relocated the episcopal seat there at some point between 1072 and 1092. According to James Essex, Remigius set the foundations of his Cathedral in 1072, and it is likely that, being a Norman, he recruited Norman masons to supervise the construction, albeit he was unable to finish the construction before his death. When Lincoln Cathedral was initially erected, William the Conqueror handed Remigius the parish of Welton in order to fund six prebends, which generated money for the cathedral’s six canons. St Mary’s Church in Stow had formerly been regarded as Lincolnshire’s “mother church”.

Lincoln Cathedral, on the other hand, was more central to a diocese that spanned from the Humber to the Thames.

Remigius constructed the original Lincoln Cathedral in its current location, completed it in 1092, and died two days before it was dedicated on the 7th of May, 1092. A fire damaged the wooden roofing in 1124. The cathedral was repaired and enlarged by Alexander, but it was significantly damaged by an earthquake 40 years later, in 1185. This earthquake was among the most powerful ever felt in the United Kingdom, with a magnitude of more than five. The cathedral is said to have suffered considerable damage, with the building splitting from bottom to top; in the current structure, only the lower section of the west end and its two linked towers survive from the pre-earthquake Lincolnshire cathedral.

Some contend that the cathedral’s damage was made worse by subpar design or construction, referring to the building’s actual collapse as being brought on by a failure in the vault. A new bishop was selected following the earthquake. His name was Hugh de Burgundy of Avalon, France, and he was the man behind the huge renovation and enlargement project that followed after his appointment. This Lincolnshire cathedral swiftly adopted other architectural advancements of the time, adding flying buttresses, pointed arches, and ribbed vaulting. This provided support for the incorporation of bigger windows.

Eleanor of Castile died in 1290, after which King Edward I arranged an exquisite funeral procession to honor his Queen.

Eleanor’s organs were interred in Lincoln Cathedral when her body was embalmed, which in the 13th century included a procedure known as evisceration and King Edward placed a replica of the Westminster Abbey monument there. The Lincoln tomb’s original stone chest still stands, but the effigy was torn down in the 17th century and substituted with a 19th-century replica.

Two famous sculptures on the exterior of Lincoln Cathedral have often been identified as representing Eleanor and Edward, however, the images were significantly repaired in the 19th century and were probably not originally meant to portray the royal couple. The Lincolnshire cathedral’s ornately carved screen and 14th-century misericords, as well as the Angel Choir, were also added during this period. For most of the cathedral’s length, the walls contain relief arches with an additional layer in front to create the appearance of a corridor down the wall. However, the illusion does not work because the stonemason, who copied French techniques, did not create the arches with the necessary length for the illusion to take effect.

Wartime History

Billy Strachan, a skilled RAF pilot, nearly crashed his aircraft into the cathedral during the late stages of WWII. Strachan attributed his flight career ending to this encounter because he felt mentally incapable of continuing to fly combat missions. During WWII, numerous Bomber Command airfields were located in Lincolnshire.

The adjacent RAF Waddington station insignia displays Lincoln Cathedral emerging above the clouds.

Until the completion of the RAF Bomber Command Memorial in 2012, the Lincoln Cathedral was the sole memorial in the U.K. devoted to the significant losses of pilots in World War II suffered by Bomber Command. During the war, extremely valuable British treasures were safely stored in a room 60 feet beneath the Lincolnshire cathedral. The copy of the Magna Carta that belonged to the cathedral was not included since it was on loan in America.

The Lincoln Cathedral in the 21st Century

In the year 2000, the Western Front received a comprehensive makeover. The eastern end’s flying buttresses were discovered to be disconnected from the neighboring stonework, and restorations were done to prevent collapse. Furthermore, the masonry of one of the windows in the transept was cracking, necessitating a complete rebuilding of the window in accordance with the International Council on Monuments and Sites conservation requirements. When it was discovered that the masonry just needed to shift 5 mm for the entire window to fall, there was a moment of immense concern. Engineers stripped the tracery from the window before constructing a stronger, more sturdy substitute.

Furthermore, the old stained glass was cleaned and placed behind a new transparent isothermal glass that provides better protection from the weather. A statement in January 2020 revealed that archaeologists had discovered over 50 burial sites during renovations since 2016, notably a priest buried with a paten and chalice. Sections of some elaborately adorned Roman houses and accompanying artifacts were also uncovered during the dig. Some of the Roman, medieval, and Saxon artifacts were to be shown at the tourist center, which was set to open in late 2020. After 36 years, the scaffolding on the west façade of Lincoln Cathedral was dismantled in 2022.

The Architectural Features of the Lincoln Cathedral

Now that we have covered the history of the Lincoln Cathedral, we can look at some of its most notable features. Lincoln Cathedral is one of the few English churches made entirely of the rock on which it stands, as It’s largely made of Lincolnshire Limestone.

Stonemasons at the cathedral utilize more than 100 tonnes of stone every year for its upkeep and repairs.

The Lincoln Cathedral Imp

The Lincoln Imp is one of the cathedral’s stone sculptures. The tale around the figure has multiple versions. According to 14th-century folklore, Satan dispatched two naughty imps to cause mischief on Earth. After wreaking havoc in other parts of Northern England, the two imps made their way to Lincoln Cathedral, where they destroyed chairs and tables and even tripped the bishop. In the Angel Choir, an angel approached and told them to halt.

One of the imps stood on a stone pillar and began hurling stones at the angel, while the other hid behind the shattered tables and chairs. The first imp was turned to stone by the angel, enabling the second imp to flee. The imp who turned to stone may still be observed in the Angel Choir, on his stone column. They are also among several carved animals that can be found in the building.

Rose Windows

Lincoln Cathedral has two large rose windows, which are quite rare in English medieval architecture. The Dean’s Eye on the northern side of the Lincoln Cathedral still exists from the initial structure of the cathedral while the Bishop’s Eye on the southern side was most likely erected sometime between 1325 and 1350. This southern window has one of the most extensive instances of curvilinear tracery in medieval architecture. Curvilinear tracery is a tracery technique in which the patterns are made up of continuous curves.

Because squared windows and pointed arches are the easiest designs to create, the circular area of the window presented a new challenge to the architects.

A technique was devised that called for the circle to be broken into smaller forms to make design and creation easier. Within the window, curves were created to produce four unique regions of a circle. The areas within the circle where the tracery would go became significantly smaller and easier to deal with as a result.

This window is also notable for shifting the tracery’s focus away from the core of the circle and towards other regions. Because the glazing was as difficult to deal with as the tracery for many of the exact same reasons, the designers reduced the quantity of iconography within the window. During this historical period, most cathedral windows displayed numerous vibrant images of the Scriptures; yet, there are very few images at Lincoln Cathedral. Saints Andrew, Paul, and James are among the pictures seen in the glass-stained window.

Vaults

The vaults are a significant architectural element of Lincoln Cathedral. The cathedral’s several vaults are thought to be both unique and experimental. The vaults of the aisles, nave, chapels, and choir varied. There is an uninterrupted ridge rib with an ordinary arcade that overlooks the bays along the North Aisle. There is an irregular ridge rib in the Southern Aisle that emphasizes each bay. The vaults of the North West Chapel are quadripartite, whereas the vaults in the South Chapel are stemmed from a single central support column.

The incorporation of sexpartite vaults enabled greater amounts of sunlight to enter the cathedral via clerestory windows set inside each of the bays.

A series of asymmetrical vaults in Saint Hugh’s Choir appears to be a diagonal line created by two ribs on one side of the vault turning into a single rib on the other side of the vault. This design splits the space between the bays and vaults, emphasizing the bays. The chapter house is a decagonal structure with only a single main column from which 20 ribs rise, creating distinctive vaulting. The varied vaults of the space are the only way to identify each part of Lincoln. Each vault, or vault variant, is distinct. Geoffrey de Noiers, a French-Normand master mason, is credited with creating the vaults. Alexander the Mason followed him, and he created the nave’s more complex but symmetrical tierceron style vaulting, Galilee Porch, crossing vaulting, and western facade screen.

Organ

The cathedral organ, one of the outstanding examples of “Father” Henry Willis’ work and the final instrument that he designed before his passing away, dates from 1898. Willis had finished the design by 1885, but a financing shortage delayed building and installation. This was made possible by Alfred Shuttleworth’s £1,000 contribution in 1898. This, together with additional individual contributions and a public subscription, enabled the work to continue.

The organ was dedicated on St Hugh’s Day, on the 17th of November 1898, at a liturgy attended by around 4,700 people.

Willis planned for the organ to be electrically operated, making it the first in an English cathedral to be run in this manner. Because the Brayford Wharf Power Station had not yet been constructed, the Lincolnshire Regiment supplied manual power. The organ was repaired twice, once in 1960 and once in 1998. Harrison & Harrison handled the job on both occasions. It serves as one of only two Willis organs in English cathedrals that still have its original tonal design.

Tower Clock and Bells

In 1775, John Thwaite placed a clock in the north-western tower. Benjamin Vulliamy later modified it and transferred it to the wide tower in 1835. It was substituted in 1880 by a new clock designed by Edmund Beckett QC and manufactured by Potts & Sons of Leeds. This new clock included Cambridge Chimes. The clock’s striking mechanisms require winding on a daily basis, which takes around 20 minutes when done manually.

The cathedral’s South West tower houses a beautiful ring of 13 bells made by John Taylor & Co in Loughborough. The back eight bells were cast in 1913, and four additional trebles were added in 1927. A flat sixth was installed in 1948 to facilitate ringing on the middle eight bells. The bells sound from a part of the tower right above The Great Western Front, with three windows placed on each but one side of the ringing chamber. The bells are suspended beneath the louvers to reduce the tower’s movement as much as possible.

Lincoln Cathedral, the third-largest English Cathedral and unquestionably one of the most pleasurable to see. It is also one of the pinnacles of Gothic architecture. It is regarded as a beautifully harmonized display of ornamental art. The western front is extremely beautiful, with its Norman arches set on a 13th-century screen. The amount of sculptural detail alone is worth several hours, if not days, of study. After fires and earthquakes forced the reconstruction of sections of the Lincoln Cathedral, it adopted a Gothic architectural style. When the central spire was finally constructed in 1311, it surpassed the Great Pyramid of Giza as the highest edifice in the world. This lasted until 1549, when the spire was destroyed by a storm.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can You Visit Lincoln Cathedral?

Admission to Lincoln Cathedral includes guided floor tours. A tour with one of the Lincolnshire Cathedral’s knowledgeable guides is one of the greatest ways to view this amazing architecture if you’re here for the first time. You may also schedule one of the specialist tours of the cathedral to enrich your visit even more. Floor tours are available all year and are suited for all ages. They typically take about an hour and cover all elements of the Cathedral, including design, history, and a few amusing anecdotes tossed in for good measure. You’re able to tour the top area of Lincoln Cathedral, which offers panoramic views of the city. Additionally, you can ascend more than 300 steps to the summit of Lincoln Cathedral’s Central Tower and enjoy spectacular 360-degree views over the city and beyond.

Why Is the Lincoln Cathedral Renowned?

Lincoln Cathedral is a magnificent Gothic structure filled with treasures. The construction of this spectacular church, with its amazing pointed arches, rib vaulting, and brilliant stained glass windows, began in 1192. In contrast, the spectacular chapter house features fan vaulting and, interestingly, was where several sequences from the film, The Da Vinci Code, were shot. If you look carefully, you will notice finely carved misericords, as well as a stone creature known as the Imp. The tomb for Queen Eleanor of Castile’s organs is located in the nave, opposite the Lincoln Cathedral entrance.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Lincoln Cathedral – The History of the Famous Cathedral.” Art in Context. September 6, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/lincoln-cathedral/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 6 September). Lincoln Cathedral – The History of the Famous Cathedral. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/lincoln-cathedral/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Lincoln Cathedral – The History of the Famous Cathedral.” Art in Context, September 6, 2023. https://artincontext.org/lincoln-cathedral/.