Pyramids of Giza – Everything About the Great Pyramids of Giza

All around the world, ancient humans have built pyramid-like structures such as temples, tombs, and shrines. The finest of these are arguably the Pyramids of Giza and the Great Pyramid of Giza is the most popular of those found at this ancient site. But, why was the Pyramid of Giza built, who built the Great Pyramid of Giza, and what happened to the Great Pyramid of Giza? This article will answer all these questions about the Pyramids of Giza, specifically those referring to the most significant of the group, the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The Ancient Pyramids of Giza

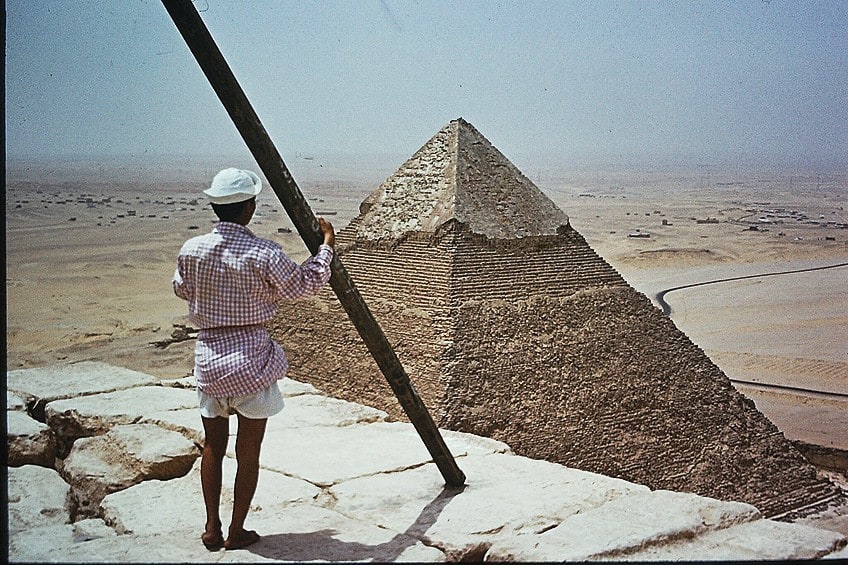

When were the Pyramids of Giza built and which is the largest pyramid in Giza? The plateau’s three principal pyramids were erected over successive generations by the emperors Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure. Each pyramid consisted of an imperial funeral structure that also contained a temple at its foot and a lengthy stone causeway. The biggest of these structures is the Great Pyramid of Giza, built as the tomb of Khufu. Where is the Great Pyramid of Giza located? Giza is a city in the Metropolitan area known as Greater Cairo in Egypt, and the pyramids are located on the Giza plateau.

We are accustomed to seeing the Giza Pyramids in captivating images, where they look like gigantic and inaccessible structures towering from an empty, barren desert. Visitors may be astonished to learn that a golf club and resort are only a few 100 feet from the Great Pyramid of Giza and that Giza’s growing suburbs have stretched all the way up to the base of the Sphinx.

These unique representations of world cultural heritage are now under threat from urban growth and the issues that come with it, such as contamination, garbage, illicit activities, and vehicle traffic. Aside from the primary pyramids, other smaller pyramids assigned to queens are organized like satellites. A huge cemetery complex of smaller tombs called mastabas occupies the region west and east of Khufu’s pyramid. These were built for significant members of the court and were placed in a grid layout. Being interred near the emperor was a high honor that guaranteed a coveted position in the Afterlife.

Construction of the Pyramids of Giza

Much uncertainty remains regarding how these gigantic structures were built, and various theories and ideas exist concerning the real techniques that were utilized. The manpower required to construct these structures is also always being debated. Who built the Great Pyramid of Giza and its surrounding structures? The unearthing of a workers’ village at the southern end of the plateau has provided some explanations. A permanent team of professional artisans and architects was most likely reinforced by seasonal groups of around 2000 peasant workers.

These crews were organized into 200-man gangs, with each unit further subdivided into 20-man teams. Experiments demonstrate that teams of 20 workers could transport the 2.5-ton stones from quarries to pyramids in around 20 minutes, thanks to a slick surface of moist silt. When many of the blocks were significantly smaller, an approximated 340 stones could be carried daily from the quarries to the building site of the Pyramids of Giza.

Preservation and Status of the Pyramids of Giza

The Pyramids of Giza are one of the most significant of the Seven Wonders of the World and were also included in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1979, and the agency has funded over a dozen expeditions to assess their condition since 1990. It has backed the repair of the Sphinx as well as initiatives to reduce the effects of tourism and regulate the expansion of the surrounding community. Nonetheless, threats to the monuments persist: air pollution contributes to stone erosion, and vast illicit sand mining on the surrounding plateau has left gaps large enough to be visible on Google Earth.

Egypt’s 2011 revolutions and their turbulent economic and political aftermath also had a detrimental influence on tourism, one of the country’s most vital businesses, and tourist numbers are just now starting to climb again.

UNESCO has kept a close eye on these challenges, but its most important role at Giza has been to argue for the reconfiguration of a roadway that was initially planned to connect the pyramid complex to the necropolis of Saqqara. Ultimately, the government decided to develop the motorway north of the pyramid complex.

Nevertheless, as the Cairo metropolitan region grows, designers are now considering the construction of a multilane tunnel beneath the Giza Plateau. ICOMOS and UNESCO have called for in-depth analyses of the project’s possible effects, as well as an overarching site management strategy for the pyramids of Giza, which would include methods to mitigate the ongoing impact of unlawful waste dumping and quarrying. The Pyramids of Giza, no matter how huge they are, are not indestructible. With Cairo’s fast expansion, they will require enough care and preservation if they are to stay intact as significant monuments of ancient history.

The Great Pyramid of Giza

| Architect or Pharoah | Khufu (4th Dynasty) |

| Date | c. 2570 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone, mortar, granite |

| Location | Giza Plateau, Cairo, Egypt |

The incredible thing about the Great Pyramid of Giza is that it is both the oldest and the only of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World to still be mainly intact. For over 3,800 years, it also held the title of the tallest structure made by human hands. At one point, the pyramid was covered in a casing of smooth limestone which was removed over the ages, causing the pyramid’s height to lessen. How big is the Pyramid of Giza today, though? Currently, the pyramid measures 138 meters in height.

The burial complex around the pyramid included two mortuary temples linked by a causeway, graves for Khufu’s close relatives and entourage, three lesser pyramids for the pharaoh’s wives, another satellite pyramid, and five solar barges that had been buried.

Who Built the Great Pyramid of Giza?

Historically, the Great Pyramid of Giza was credited to Khufu based on the assertions of the ancient historical writers, most notably Diodorus Siculus and Herodotus. Yet, during the Middle Ages, a range of various figures, including Nimrod, Joseph, and King Saurid, was attributed to erecting the Great Pyramid of Giza. After tunneling to them, four further chambers were discovered above the King’s Chamber in 1837. The previously unexplored rooms were now coated in red-painted hieroglyphs. The laborers who were constructing the Great Pyramid of Giza had labeled the blocks with the names of their groups, which also included the title of the pharaoh.

The name Khufu was written on the walls several times. Goyon discovered another of these inscriptions on an external block of the pyramid’s fourth tier. The markings are similar to those found at other Khufu locations, such as the port at Wadi al-Jarf or the alabaster quarry at Hatnub, and are also found in the pyramids of other emperors.

The graves near the pyramid were unearthed during the 20th century. Khufu’s relatives and important individuals were interred in the Eastern and Western Fields. This included the brides, offspring, and grandchildren of Khufu, Ankhaf, and Hemiunu. Hassan explains: “From early dynastic times, it was customary for family, associates, and consorts to be buried beside the monarch they had served throughout their lifetime. This was entirely consistent with the Egyptian concept of an afterlife”.

The Age of the Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid’s age has been estimated indirectly through its designation to Khufu and his historical age, relying on archaeological and literary sources, and directly using radiocarbon dating of biological materials discovered in the Great Pyramid of Giza and incorporated in the mortar. Previously, the Great Pyramid of Giza was dated by its designation to Khufu alone, placing the pyramid’s construction during his reign. Thus, dating the pyramid meant determining the date of Khufu’s reign and the 4th dynasty. The relative sequencing and synchronization of occurrences are important to this strategy.

Definitive calendar dates are obtained from an interconnected network of data, the foundation of which is ancient king records and other documents. The reign durations from Khufu to recognized dates in the past are summarized and supported by genealogical information, astronomical measurements, and other references. As a result, Egypt’s historical chronology is essentially political and hence distinct from other forms of archaeological findings such as material culture, stratigraphies, or radiocarbon dating. The great majority of current chronologies place Khufu’s pyramid between 2,700 and 2,500 BCE.

Radiocarbon Dating

Mortar was used liberally in the Great Pyramid’s construction. Ashes from fires were included in the mortar during the mixing process, as well as organic materials that could be removed and radiocarbon dated. Between 1984 and 1995, over 45 mortar samples were collected to ensure that they were obviously intrinsic to the original construction and could not have been added at a later period.

The findings were calibrated between 2,871 to 2,604 BCE. Since the age of the organic material was established, not when it was last utilized, the old wood is considered to be primarily responsible for the 100 – 300-year discrepancy. Based on the younger samples, a data reanalysis reported that the pyramid was completed between 2,620 and 2,484 BCE.

Dating the Great Pyramid in the Past

Herodotus assigned the Great Pyramid to Cheops (Hellenized to Khufu) in 450 BCE, but erroneously dated his rule after the Ramesside dynasty. Around 200 years later, Manetho compiled an exhaustive list of Egyptian monarchs, which he grouped into dynasties, with Khufu assigned to the 4th. Nevertheless, due to phonetic alterations in the Egyptian language and, as a result, the Greek translation, “Cheops” became “Souphis”. Greaves stated in 1646 the tremendous difficulty in determining a date for the pyramid’s development based on a scarcity of and contradicting historical data. He didn’t identify Khufu on Manetho’s king list because of the abovementioned spelling inconsistencies, so he relied on Herodotus’ inaccurate version. Greaves decided that the year 1,266 BCE marked the commencement of Khufu’s reign by summarizing the length of lines of succession.

Some of the gaps and inconsistencies in Manetho’s chronology were filled 200 years later by discoveries like the King Lists of Abydos, Turin, and Karnak. The names of Khufu discovered in the Great Pyramid’s Relieving Chambers in 1837 aided in establishing that Cheops and Souphis are one in the same person.

As a result, the Great Pyramid of Giza was identified as having been constructed during the 4th dynasty. Egyptologists’ dating still differed by centuries, based on technique, previous religious views, and which sources they considered were more genuine. Estimates shrank substantially in the 20th century, with the majority falling within 250 years from each other, all around the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE. The newly established radiocarbon dating technology proved that the historical chronology was close. Nevertheless, due to greater margins of error, calibration errors, and the problem of intrinsic age in organic material, especially wood, it is still not a completely acknowledged technology. Additionally, astronomical alignments that correlate with the period of construction have been proposed.

Historic Documentation of the Great Pyramid of Giza

One of the first prominent writers to describe the pyramid is the 5th-century BCE Greek historian Herodotus. Yet another writer, Diodorus Siculus, an ancient Greek historian, visited Egypt between 60 and 56 BCE and later dedicated the first volume of his Bibliotheca Historica (1522) to the region’s history, and its structures, including the Great Pyramid of Giza. Pliny the Elder, a Roman writer who lived in the 1st century CE, stated that the Great Pyramid of Giza was erected to either “keep the lower classes from staying uninhabited” or to prevent the treasures of the pharaoh from slipping into his enemies or successors’ hands.

Herodotus

Herodotus examines Egypt’s history and the Great Pyramid of Giza in the second book of his opus The Histories (430 BCE). This account was written more than 2000 years after the pyramid was erected, implying that Herodotus received his information mostly from indirect sources like low-ranking authorities and clergy, native Egyptians, immigrants from Greece, and Herodotus’ own translators. As a result, his explanations appear as a jumble of coherent observations, personal depictions, inaccurate reports, and fictional stories; consequently, Herodotus and his writings are responsible for many of the speculative inaccuracies and confusion concerning the monument.

Herodotus claims that the Great Pyramid of Giza was erected by Khufu, who ruled after the Ramesside Period. According to Herodotus, Khufu was a tyrant, which may illustrate the Greeks’ belief that such structures could only be built through the ruthless exploitation of the people.

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus’ work was influenced by writers of the past, but he also differentiated himself from Herodotus, whom Diodorus argues recounts tales and fables. Diodorus apparently derived his information from the lost works of Hecataeus of Abdera, and, like Herodotus, he dates the pyramids to the time of the architect “Chemmis”, after Ramses III. Based on this document, neither Khufu nor Khafre were laid to rest in their pyramids, but instead in secret locations, for fear that the individuals who were presumably made to construct the edifices would seek out the bodies for vengeance; with this assumption, Diodorus bolstered the link between pyramid constructing and slavery.

Strabo

Strabo, a Greek geographer, historian, and philosopher visited Egypt in 25 BCE, just after the Romans captured it. In his book Geographica, he claims that the pyramids of Giza were used for kings’ burials, although he doesn’t say which monarch was buried there. “At a considerable height, inserted in one of the pyramid’s sides is a rock, which can be pulled out; when that is withdrawn, there is an angled path to the tomb”, Strabo adds.

This comment has sparked a lot of discussions since it implies that the pyramid might be entered at this location.

Pliny the Elder

Pliny the Elder stated that the Great Pyramid of Giza was erected to protect the pharaoh’s treasures from slipping into the hands of his enemies or successors. Pliny makes no guesses about the pharaoh in question, stating simply that “chance has relegated to obscurity the names of those who constructed such colossal relics of their pride”.

When asked how the stones were brought to such a great height, he offers two theories: either large mounds of salt and niter were built up against the pyramid and subsequently melted away with water diverted from the river, or the stones were delivered by water diverted from the river. Or that “bridges” were built, and their bricks were subsequently dispersed for the construction of private homes, claiming that the river’s level is too low for channels to ever convey water up to the pyramid.

The Pyramid of Khafre

| Architect or Pharoah | Khafre (4th Dynasty) |

| Date | c. 2,570 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone |

| Location | Giza Plateau, Cairo, Egypt |

Throughout the First Intermediate Period, the Khafre pyramid was most likely opened and looted. On Ramesses II’s orders, the supervisor of temple construction brought casing stones to construct a temple at Heliopolis during the 19th Dynasty. The structure was inaugurated in 1372 CE, according to Ibn Abd al-Salam. An Arabic graffito on the wall of the burial room possibly comes from the same period. The Khafre pyramid was first investigated in current history by Giovanni Belzoni on the 2nd of March 1818, when the main entrance on the northern side was discovered. Belzoni hoped to find an undisturbed burial, but the room was barren but for an open sarcophagus with a shattered lid on the floor.

John Perring led the first comprehensive investigation in 1837. Auguste Mariette partly excavated Khafre’s valley temple in 1853, and while finishing its clearing in 1858, he discovered a diorite figure of Khafre.

Construction of the Khafre Pyramid

A rock outcropping was employed in the core, similar to the Great Pyramid. The northwestern corner was excavated 10 meters out of the rock substructure due to the inclination of the plateau, and the southeastern corner was developed. The pyramid is constructed of horizontal courses. The stones utilized at the bottom are relatively massive, but as the pyramid climbs, the stones grow smaller, with the peak being just 50 centimeters thick. The courses are coarse and uneven during the first half of the pyramid’s height, but a small band of regular brickwork is seen in the pyramid’s center.

The bedrock was shaped into steps at the pyramid’s northwest corner. Pink granite was used for the lowest course of casing stones, whereas Tura limestone was used for the rest of the pyramid. Close inspection indicates that the surviving casing stones’ corner edges are not perfectly straight but are offset by a few millimeters. According to one idea, this is attributed to settlement from seismic activity. Due to the restricted working area at the summit of the pyramid, another explanation proposes that the gradient on the blocks was cut to form before being put.

Interior Construct the Khafre Pyramid

There are two entrances to the burial chamber: one 11.50 meters up the pyramid’s face and one near the pyramid’s base. These tunnels do not line up with the pyramid’s midline but are displaced to the east by 12 meters. The bottom descending corridor is totally cut out of the bedrock, dropping, horizontally flowing, then rising to connect with the horizontal passageway going to the burial chamber.

One explanation for the two entrances is that the pyramid’s northern foundation was planned to be moved 30 meters to the north, making Khafre’s monument much bigger than his father’s.

This would situate the entrance to the lower route within the pyramid’s stonework. While the bedrock on the northern side is cut away from the pyramid more than on the western edge, it is unclear if there is enough area on the plateau for the perimeter wall and pyramid platform. Another argument is that, like many older pyramids, plans were revised and the entrance was relocated during construction. An auxiliary chamber, similar in length to Khufu’s King’s Chamber, opens to the west of the lower tunnel, the function of which is unknown. It might be used to house sacrifices, burial goods, or as a serdab chamber. The top descending passageway is made of granite and connects to the horizontal corridor leading to the burial chamber.

The Pyramid of Menkaure

| Architect or Pharoah | Menkaure (4th Dynasty) |

| Date | c. 2,510 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone, red granite, white limestone |

| Location | Giza Plateau, Cairo, Egypt |

The pyramid’s construction date is uncertain since Menkaure’s rule was not precisely defined, although it was most likely completed in the 26th century BCE. It is located in the Giza necropolis, a few hundred meters southwest of its bigger companions. The mortuary temple’s foundations and central region were constructed of limestone. The flooring was constructed with granite, and portions of the walls were covered with granite. Stone was used to construct the valley temple’s foundation, but unfinished bricks were used to finish both temples.

Between 1908 and 1910, an American archaeologist named George Andrew Reisner excavated the temple in Menkaure Valley. He discovered a great number of sculptures, primarily depicting Menkaure alone or as part of a group. All of these were intricately carved in the Old Kingdom’s realistic style.

Inside the Pyramid

On the 28th of July, 1837, Howard Vyse uncovered the remnants of a wooden anthropoid coffin etched with Menkaure’s title and bearing human bones in the top antechamber. This is currently thought to be a Saite-era replacement coffin. The bones were radiocarbon dated and found to be less than 2,000 years old, indicating either an all-too-common mishandling of remnants from another site or accessibility to the pyramid throughout the Roman era. The above-mentioned anthropoid coffin lid was securely transferred to England and is now on display at the British Museum.

The Queen’s Pyramids

South of Menkaure’s pyramid is three lesser pyramids, each with its own temple and substructure. The easternmost pyramid is the biggest and most imposing. Its casing is made largely of granite, like the primary pyramid, and is thought to have been finished owing to the nearby limestone pyramidion. The other two never got past the creation of the inner core. Reisner hypothesized that the buildings were tombs for Menkaure’s queens and that the people buried there were maybe his half-sisters.

The third little pyramid, according to archaeologist Mark Lehner, has a layout similar to a ka pyramid, which would have contained a statue of the monarch rather than a body.

Attempted Demolition of the Pyramid of Menkaure

In 1196, Al-Aziz Uthman, Saladin’s son and Egypt’s Sultan, sought to dismantle the pyramids, beginning with Menkaure’s. Workmen hired to deconstruct the pyramid lasted for eight months but discovered that it was nearly as expensive to destroy as it was to create. Each day, they could only extract one or two stones. Some moved the stones with levers and wedges, while others pulled them down using ropes. When a stone dropped, it would bury itself in the sand, necessitating extreme measures to extricate it. The stones were cut into multiple pieces using wedges, and a wagon was used to transport them to the base of the escarpment, where they were abandoned.

Built during a period when Egypt emerged as one of the world’s most powerful and wealthy civilizations, the pyramids, particularly the Great Pyramids of Giza, are among the most stunning man-made buildings in history. Their huge scale represents the pharaoh’s unique importance in ancient Egyptian culture. Though pyramids were constructed from the start of the Old Kingdom until the end of the Ptolemaic period in the 4th century CE, the pinnacle of pyramid construction started at the end of the third dynasty and lasted until the sixth. The Pyramids of Giza maintain much of their magnificence even after more than 4,000 years, giving a look into the country’s wealthy and historic history.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Is the Great Pyramid of Giza Located?

The Great Pyramid can be found on the Giza plateau. This is located in Cairo in Egypt. Despite how it looks in travel photos, the pyramids are not located far from civilization. In fact, they border the city of Cairo.

What Happened to the Great Pyramid of Giza?

One amazing thing about the Great Pyramid of Giza is that it is the most ancient of all the Seven Wonders, it is the only one that still is mostly extant. So to answer the question of what happened to it – it still exists up to the present day! In fact, you can go visit the pyramids any time you want – as long as you can afford the plane ticket!

Why Was the Pyramid of Giza Built?

The Great Pyramid of Giza was built to house the body of the Pharaoh Khufu. It also housed the bodies of his relatives. All of the pyramids at Giza were constructed for the various pharaohs who reigned during their erection.

When Were the Pyramids of Giza Built?

The Pyramids of Giza, designed to last forever, have done exactly that. The enormous tombs date back 4,500 years to Egypt’s Old Kingdom culture. The three iconic pyramids of Giza, as well as their vast burial grounds, were constructed in a frenzied period between around 2550 and 2490 BCE. Pharaohs Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure constructed the pyramids.

Which Is the Largest Pyramid in Giza?

That title would go to the Great Pyramid of Giza. Who built the Great Pyramid of Giza though? It was built by the pharaoh Khufu to be used as his place of burial.

How Big Is the Pyramid of Giza?

For over 4,000 years, the Great Pyramid of Giza stood at 146.5 meters as the largest building in the world. It is currently 137 meters tall. You may be wondering how it is presently shorter than it used to be. This is because originally it was covered with flat limestone slabs. These have unfortunately long since been removed, broken, or stolen. One can only imagine how different the pyramids must have looked in their original forms before the ravages of time and looting.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Pyramids of Giza – Everything About the Great Pyramids of Giza.” Art in Context. May 31, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/pyramids-of-giza/

Meyer, I. (2023, 31 May). Pyramids of Giza – Everything About the Great Pyramids of Giza. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/pyramids-of-giza/

Meyer, Isabella. “Pyramids of Giza – Everything About the Great Pyramids of Giza.” Art in Context, May 31, 2023. https://artincontext.org/pyramids-of-giza/.