Egyptian Architecture – The Greatest Egyptian Monuments and Buildings

The history of ancient Egypt was not one long, continuous journey of a single civilization, but rather one that was full of changes and turmoil. The story of the land has been divided into various periods by scholars. The same applies to Egyptian architecture. It did not consist of one single style, but rather a multitude of styles that all evolved in their own eras, all while having certain common characteristics.

Ancient Egyptian Architecture

The most iconic architecture to be found in the region must surely be the pyramid buildings, but there are many other Egyptian monuments that also deserve attention such as tombs, temples, fortresses, and palaces. Egyptian buildings were constructed from limestone and mud bricks, which had been locally sourced.

Monumental architecture employed the construction technique known as “post and lintel”, in which massive vertical structures hold up huge horizontal structures. For the Egyptians, it was important that their buildings were in alignment with certain astronomical bodies. The columns used in Egyptian buildings were most often decorated in a manner that mimicked the look of plants that the Egyptians held in high regard, such as the papyrus plant.

The aesthetic of ancient Egyptian architecture would surface in other areas of the world over time, such as during the Orientalizing period and then once again during the period known as Egyptomania in the 19th century.

Characteristics of Ancient Egyptian Architecture

Wood was not an easily accessible building material in ancient Egypt, so bricks made from baked mud and stone were the most common materials used. Limestone was popular, as well as granite and sandstone. Bricks were usually used for town buildings and fortresses, while stone was used mostly exclusively for temples and tombs.

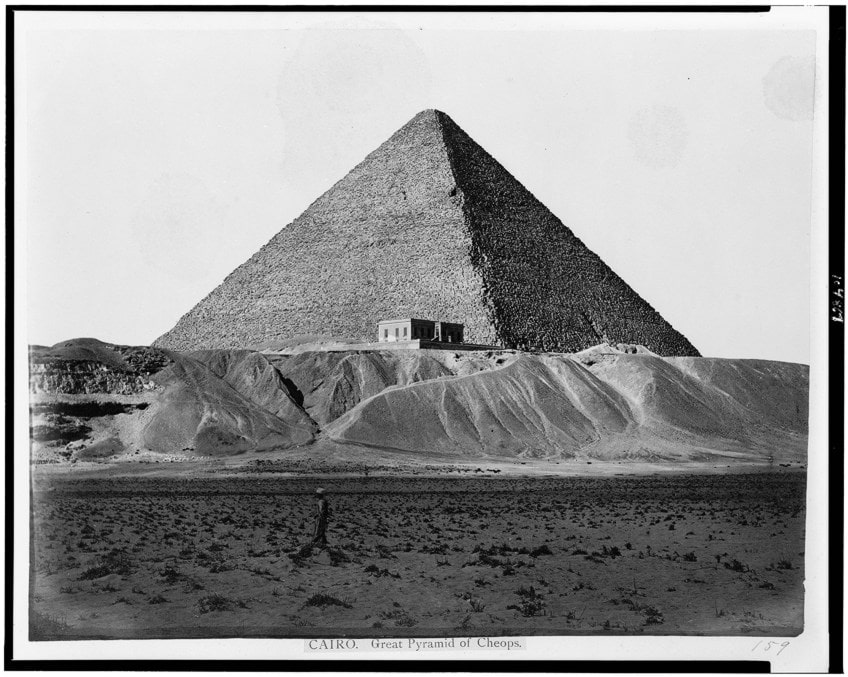

The inside of the pyramid buildings was constructed from stone sourced from local quarries as well as gravel, sand, and mud bricks. The outer shells of the Egyptian monuments were constructed from stone that had to be brought from distant regions such as Upper Egypt which was the source of red granite, and Tura, which was where the white limestone came from.

Egyptian buildings and homes were constructed from mud that had come from the Nile River’s banks. The mud was then poured into molds and dried in the blazing heat before being used for construction. The outside bricks would be highly chiseled and polished if they were intended for use in a royal tomb, such as the pyramid buildings.

Many of these Egyptian settlements have now vanished because they were constructed in the Nile Valley’s cultivated region and were drowned as the river bed gradually rose over millennia, or the mud bricks and sun-dried bricks with which they were built were used as fertilizer by peasants.

Other places cannot be reached, and some have disappeared due to the erection of new structures on top of the old ones. Due to the hot and dry climate of the region, however, a few of these mud-brick buildings still survive. This includes rare examples such as Buhen’s fortresses, the town in Kahun from the Middle Kingdom, and the village of Deir al-Madinah.

Today, most of the surviving examples that we have of tombs and temples were those that were made of stone and were constructed on ground high enough not to be affected by the flood of the Nile River.

Hence, most of what we know about ancient Egyptian architecture derives from the religious monumental architecture that was created in stone. The huge Egyptian monuments are typified by their sloped walls and sparse openings, which was most likely a technique carried through from building methods that provided some stability to mud structures. It is also likely that the style of adorning surfaces in stone buildings was copied from the style in which mud walls were decorated.

Monumental architecture did not make use of the arch until the fourth dynasty, however, the post and lintel technique was used for support strength, with large external walls made from large stones and columns holding up the flat roofs.

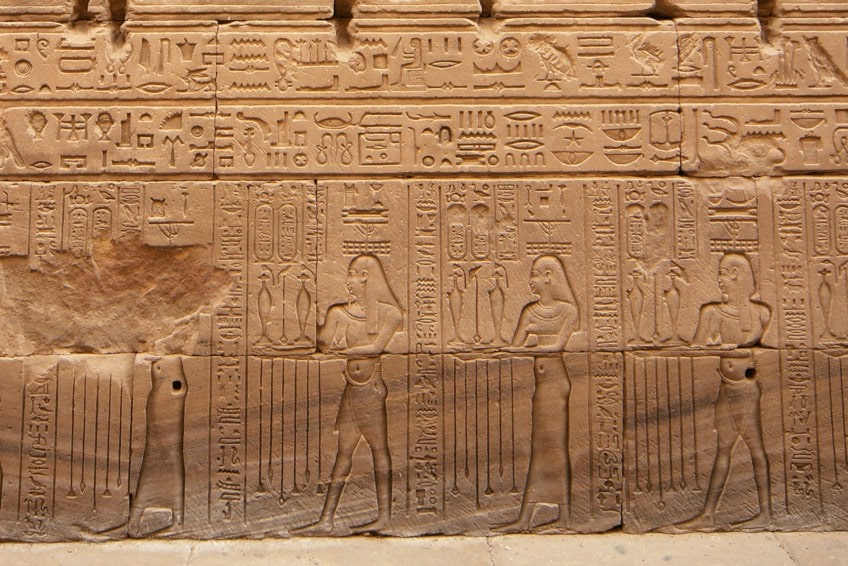

Brilliantly colored hieroglyphic carvings and frescoes cover almost every surface of Egyptian monuments, both within and without, including the piers and columns. The Egyptians incorporated symbols that portrayed vultures, solar disks, scarabs, and other objects which were symbolic to them, such as flowers, plants, and leaves.

These not only served a decorative purpose but also a historical one, allowing events and incantations to be recorded for prosperity.

Due to these hieroglyphs, we today have a deeper insight into the life and times of the ancient Egyptian people. Ancient Egyptian architecture also reveals to us that the people of ancient Egypt had a great understanding of astronomy, as their buildings aligned with certain annual events such as the equinoxes and solstices. The precision with which these calculations had to be made also indicates a high level of mathematical understanding.

Columns of Ancient Egyptian Architecture

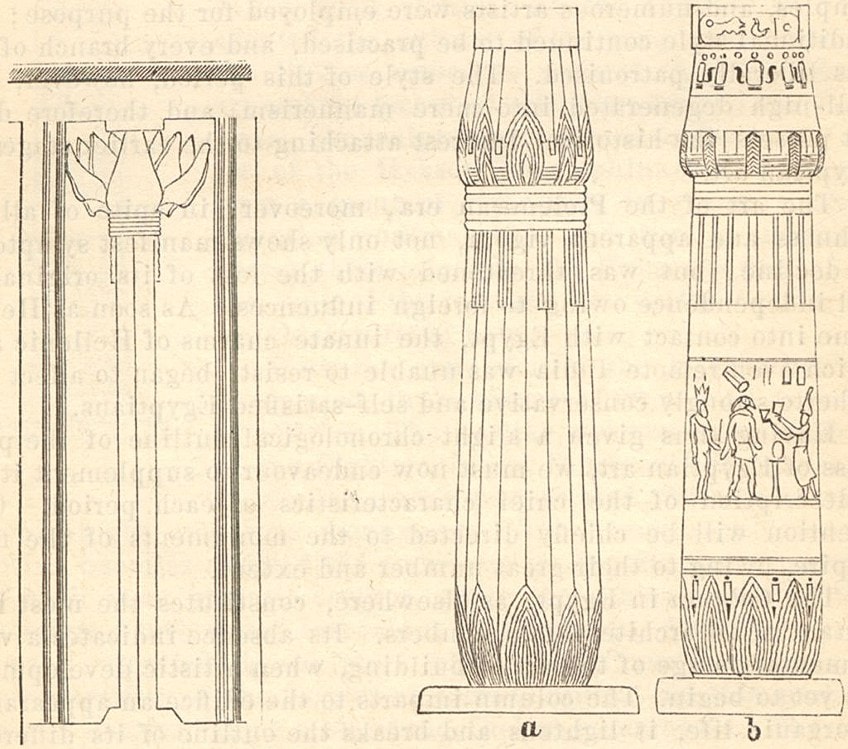

To mimic the organic shape of bundled reeds like palms, flowers, and reeds as old as 2600 BC, Egyptian builder Imhotep used etched stone columns. Intricate cylindrical shapes were also common in later Egyptian architecture. Their shape is believed to be inspired by ancient reed-built sanctuaries.

The stone columns were ornately carved and painted with hieroglyphics, inscriptions, ritualistic iconography, and natural patterns.

Papyriform columns are one of the most commonly found forms. The roots of the papyriform columns may be traced as far back as the 5th Dynasty. They’re fashioned out of lotus stems interwoven into bundles with bands. The capital, rather than extending out into a bellflower shape, at first will swell outward and then narrow down like a blossom. Stipules are a recurrent design on the base, which tapers to adopt the shape of a half-sphere, like a lily’s stem.

The columns in the Luxor Temple are suggestive of papyrus bundles, probably symbolic of the marsh where the ancient Egyptians claimed the earth was created.

Egyptian Monuments and Buildings

The monumental architecture of Egypt is famous around the globe. This is mainly due to the iconic pyramids of Giza as well as the Great Sphinx. However, there are many other examples of ancient Egyptian architecture that also deserve attention for their absolute beauty and architectural achievements.

The Pyramids of Giza Complex (2580 BCE)

| Location of Structure | Giza, Cairo, Egypt |

| Type of Structure | Monument |

| Period | Early Dynastic to Late Period |

| Architects | Unknown (c. Early Dynastic Period) |

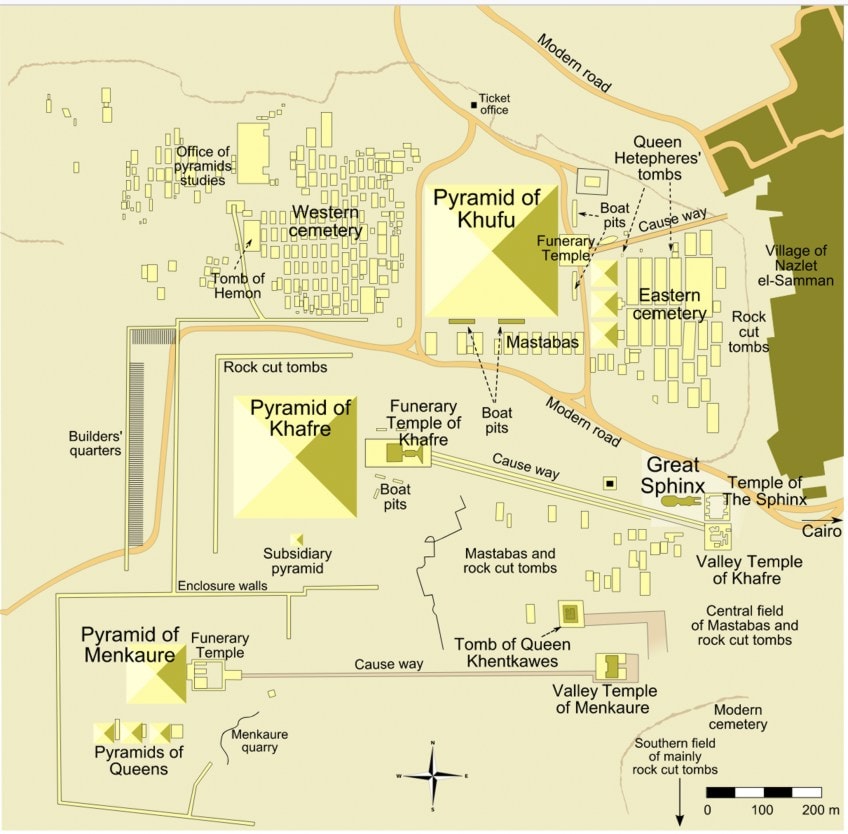

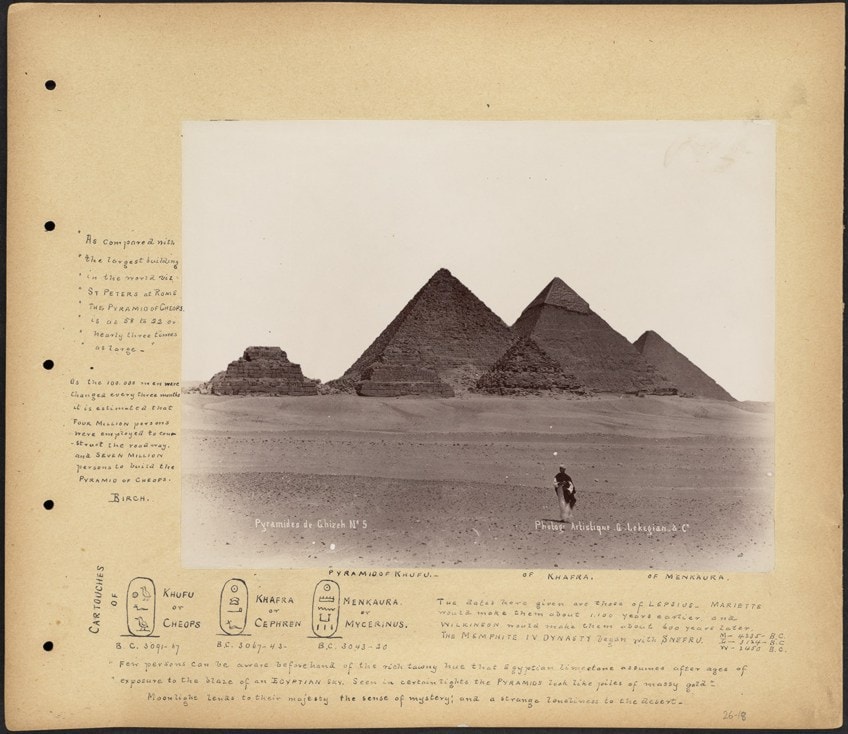

The Giza Necropolis is situated about twenty kilometers from Cairo, on the Giza Plateau. The entire complex consists of the three large iconic pyramids, as well as several other smaller pyramids, around a hundred mastabas and chapels, and of course, the Great Sphinx. The iconic pyramids date from the Fourth Dynasty and stand as witness to the strength of the Pharaohs and the power that their spiritual beliefs and ruling systems had on the ancient Egyptians. They were constructed as both burial sites and as monuments by which their names could be immortalized.

Egypt’s outstanding degree of engineering and design on a large scale is demonstrated by the massive size and straightforward shape of the buildings.

The Great Pyramid of Giza (also known as the Great Pyramid of Khafre or the Pyramid of Cheops), the biggest pyramid in the world and the first building of the Giza pyramids, was built in 2580 BC and is the only remaining construction of the Ancient World’s Wonders.

Khafre’s Pyramid is estimated to have been finished about 2532 BCE, near the end of Khafre’s rule. Khafre was foresighted enough to construct his pyramid next to his father’s. Although it is not as high as his father’s pyramid, he was able to give it the illusion of being higher by constructing it on a site 10 meters higher in elevation than the one belonging to his father.

Chefren also commissioned the construction of a huge Sphinx to serve as a guardian over his grave, in addition to his pyramid. The ancient Greeks saw a human face on a lion’s body, probably a representation of the pharaoh, as a sign of divinity 1500 years later. The Great Sphinx reaches 20 meters tall and is sculpted out of limestone bedrock.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Great Sphinx was built under Pharaoh Khafre, the mastermind behind the second pyramid of Giza, around 2500 BC.

The body stones of the Sphinx were used to build a temple in front of it, but neither the enclosure nor the temple were completed, and the scarcity of Old Kingdom cultural material implies that there was no Sphinx worship at the time.

The northern boundary barrier of the Khafre Valley Temple was to be demolished in order to create the temple, indicating that the Khafre funerary complex existed prior to the Sphinx. The enclosure’s south wall’s angle and location further imply that the causeway linking Khafre’s Pyramid and Valley Temple stood before the Sphinx was constructed.

The Sphinx Temple’s lower foundation level further suggests that it does not predate the Valley Temple.

It is believed that the Sphinx’s head may have been sculpted first, out of yardang, or possibly a side of bedrock. These can take on animal-like forms on rare occasions. El-Baz speculates that the ditch or moat around the Sphinx was quarried out later to allow for the completion of the sculpture’s complete body.

Menkaure’s pyramid is the shortest of the Great Pyramids, at 65 meters tall and dating from around 2490 BC. Pyramids, according to common perception, are incredibly perplexing, with several tunnels within the pyramid to confuse tomb robbers. This isn’t accurate. Pyramid shafts are often uncomplicated, leading directly to the tomb.

Because of the enormous scale of the pyramids, thieves were drawn to the treasure that lay within, and tombs were looted fairly soon after they were sealed in certain instances. There are occasionally further tunnels, but they were built to help the architects figure out how deep they could dig the tomb into the Earth’s crust. Another false popular belief is that successive royalty was laid to rest in the Valley of the Kings to keep their location hidden from looters.

In reality, pyramids were built for many more dynasties to come, albeit on a scale that was noticeably smaller than previously. In the end, it was various factors regarding their economy that put an end to pyramid construction and not thieves.

Luxor Temple (1400 BCE)

| Location of Structure | Luxor, Egypt |

| Type of Structure | Sanctuary |

| Period | 1400 BCE |

| Architects | Unknown (c. 1400 BCE) |

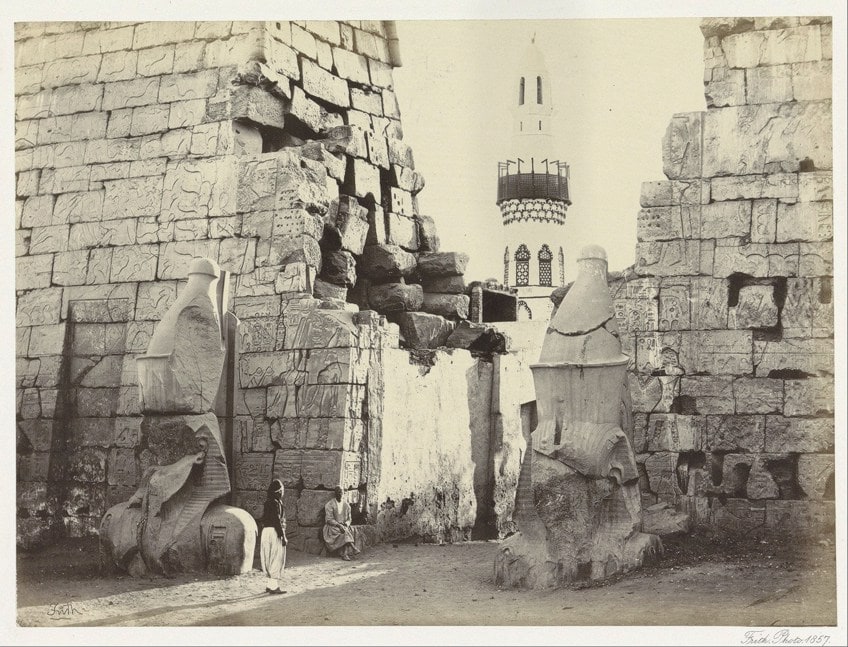

This massive temple complex is situated on the eastern bank of the Nile River in the ancient city of Thebes (modern-day Luxor). It was during Amenhotep III’s reign in the 14th century BCE that work first began on the Egyptian buildings. Pharaohs such as Tutankhamun and Horemheb made additions such as friezes, statues, and columns. After destroying all traces of the cartouches that mentioned his father, Akhenaten then created an altar to the Aten. The biggest addition to the monumental architecture happened a century after the project first began when Egypt was ruled by Ramesses II.

This makes the Egyptian buildings at Luxor different from any other, as there were only two pharaohs noted by scholars as being involved in the architectural design.

The temple complex starts with Ramesses II’s First Pylon, which is 24 meters tall. This pylon was adorned with images depicting Ramesses’ war successes, such as the one in Qadesh, as well as those of succeeding pharaohs, specifically those of the Ethiopian Dynasty and Nubian dynasty. Six huge sculptures of Ramesses lined the great temple complex’s entrance, four of them sitting and two of them upright, but only two of those sitting have remained.

A 25-meter large granite obelisk may also be seen by modern tourists; it was part of a pair until 1835 when the one was transported to Paris, where it is currently housed in the middle of the Place de la Concorde.

Ramesses II also erected a peristyle courtyard, which is accessible by the pylon gateway. This section of the temple, as well as the pylon, were constructed at an angle to the remainder of the temple, possibly to fit the three baroque shrines in the northwest corner, which were already there. The processional colonnade erected by Amenhotep III follows the peristyle courtyard – a 100-meter hallway flanked by 14 papyrus-capital columns.

Friezes on the walls depict the many stages of the Opet Festival, starting with offerings at Karnak in the upper left and continuing throughout Amun’s entrance in Luxor at the finish of that wall, and concluding with his arrival on the other side. Tutankhamun installed the decorations: the young pharaoh is portrayed, but his name has been changed by Horemheb’s.

The courtyard that extends beyond the colonnade was also constructed by Amenhotep III. The easternmost columns have the finest preservation since they still show some signs of their original hue. The 36-column hypostyle court on the southern side of the courtyard leads to the temple’s gloomy interior.

Temple of Karnak (2000 – 1700 BCE)

| Location of Structure | El-Karnak, Egypt |

| Type of Structure | Sanctuary |

| Period | The Middle Kingdom to the Ptolemaic Kingdom |

| Architects | Unknown (2000 – 1700 BCE) |

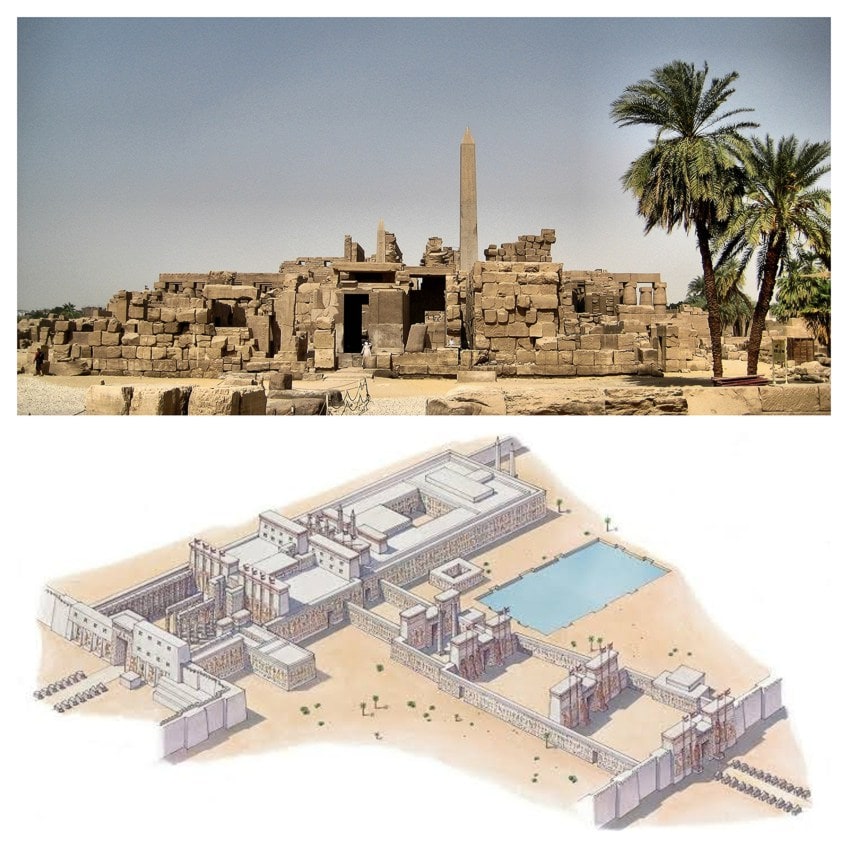

Karnak’s temple complex lies 2.5 kilometers north of Luxor on the banks of the Nile River. It is divided into quarters: the Precincts of Amon-Re, the Precincts of Montu, the Precincts of Mut, and the Temple of Amenhotep IV (demolished), and also a couple of minor shrines and protected areas outside the four main sections’ enclosing walls, and many thoroughfares of sphinxes with Ram’s heads. Several pharaohs have added to and improved upon this temple complex. However, every New Kingdom emperor made a substantial contribution to it.

There are obelisks, chapels, courtyards, halls, and other smaller temples scattered throughout the complex, which covers an area of more than 200 acres.

With regard to Egyptian monuments and temples, Karnak stands out because of how long it was constructed and utilized. Construction began in the 16th century BC on a small scale, but as many as twenty temples and chapels were erected in the main precinct alone throughout time. The structures were built by around 30 pharaohs, allowing them to reach hitherto unimaginable sizes, intricacy, and variety.

Few of Karnak’s features are unique, but the sheer scale and quantity of these features are astounding.

The temple of Amun-Re at Karnak is one of Egypt’s most important examples of ancient Egyptian architecture. This temple, like many others in Egypt, celebrates the gods and commemorates previous achievements, including thousands of years of history recorded by inscriptions on many of the walls and columns discovered on site, which were frequently changed or entirely obliterated and restored by subsequent rulers.

Amun-Re’s temple was built in thirds, the third of which was built by the pharaohs of the New Kingdom. Numerous elements of the architecture, for example, the sanctuary of the complex, were in alignment with many astronomical events such as the summer solstice sunset, as was customary in Egyptian architecture.

One of the most impressive structures on the property is the 5,000-square-meter hall, constructed during the Ramesside period. This massive hall is supported by a hundred and thirty-nine columns made from mud brick and sandstone, including 12 center columns that were formerly lavishly adorned.

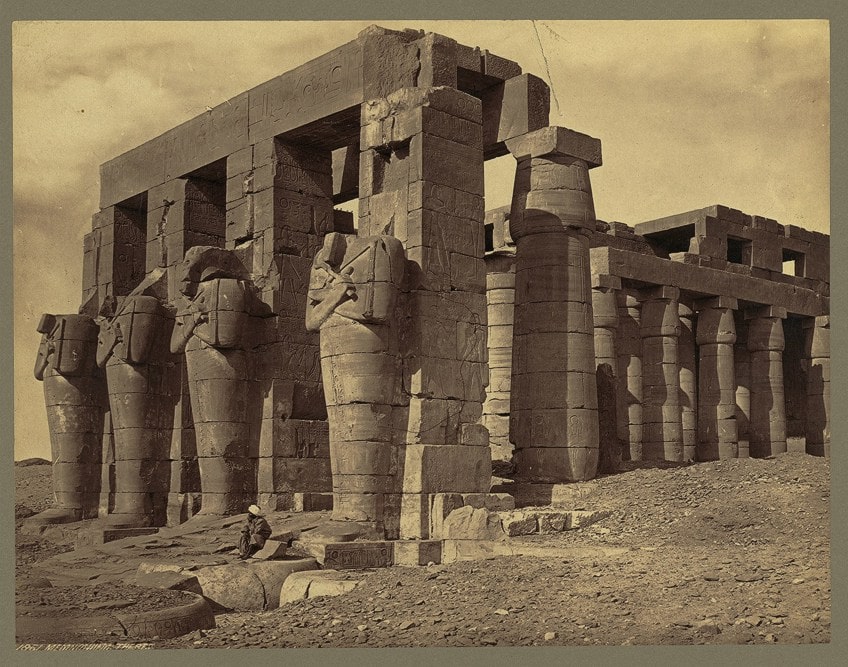

Ramesseum (c. 13th century BCE)

| Location of Structure | Luxor, Egypt |

| Type of Structure | Sanctuary |

| Period | 13th Century BCE |

| Architects | Unknown (c. 13th century BCE) |

From about 1279 to 1213 BCE, Ramesses II, a 19th Dynasty pharaoh, governed Egypt. Among his numerous achievements, including as the extension of Egypt’s frontiers, he built the Ramesseum, a huge temple at Thebes, the New Kingdom’s capital at the time.

The Ramesseum was a beautiful temple with massive sculptures guarding the entrance.

A 62-foot statue of the pharaoh himself was the most striking feature of the pyramid. This amazing pharaonic statue’s original mass and dimensions can only be estimated because of the fact that only the base and body remain. At least one depiction of Ramses’ war successes, for example, the Battle of Kadesh and the pillaging of “Shalem,” may be seen in reliefs found in the temple.

The Temple of Malkata (c. 14th century BCE)

| Location of Structure | Luxor, Egypt |

| Type of Structure | Palace Complex |

| Period | c. 14th century BCE |

| Architects | Unknown (c. 14th century BCE) |

More than 250 structures and monuments were erected during Amenhotep III’s reign. The ancient place of worship in Malkata, referred to as the “home of joy” by ancient Egyptians, was built to act as his royal home on the western bank of Thebes, to the southern side of the necropolis. About 226,000 square meters of space are occupied here.

There are several buildings, courts, parade grounds, and dwellings on the huge site. It is thought to have served as a town as well as a temple and a residence for the Pharaoh.

The Pharaoh’s residences, which included a number of chambers and courts arranged around a columned dining hall, occupied the majority of the complex’s center. A huge throne room connected to smaller rooms, for storage, waiting, and smaller audiences, accompanied the apartments, which likely housed the royal company and overseas guests. In this part of the complex, the most important structures are the Western Villas, North Palace and Village, and the Temple.

The exterior measurements of the temple are roughly 183.5 by 110.5 meters, and it is divided into two sections: the vast courtyard and the temple proper.

The huge frontcourt, which is oriented east-west and comprises the east portion of the temple complex, measures 131.5 by 105.5 meters. A modest retaining wall separates the western part of the court from the rest. The lower terrace has a square shape, while the upper terrace has a rectangle shape. In the top half of the court, mud bricks were used to cover the surface and a ramp was enclosed by walls connecting the lower forecourt to the higher landing.

The middle, north, and south components of the temple may be split into three separate sections.

A tiny rectangular anteroom (6.5 by 3.5 m) marks the middle portion, and several of the door jambs, including the antechamber, bear inscriptions such as “given lifelike Ra eternally.” The anteroom is followed by a 12.5 by 14.5-meter hall, which is accessed by a 3.5-meter wide entrance in the middle of the dividing panel. There is an indication that this chamber’s ceiling was formerly painted with yellow stars on a blue backdrop, but today’s walls merely appear to be white stucco over mud plaster.

In light of the numerous decorative plaster fragments found in the room’s deposit, we may assume that these were ornately decorated as well. The ceiling is supported by six columns arranged in two rows, east-west. There are just a few fragments of the column bases left, but they suggest that the columns had a diameter of about 2.25 m. The columns are 2.5 meters away from the walls, and each row is around 1.4 meters apart, with a 3-meter space between them.

The second hall may be accessed through a 3-meter-wide entrance in the center of the first hall’s rear wall.

The second hall is comparable to the first in that its ceiling is adorned with patterns and pictures that are similar, if not identical, to the first. As with the first hall’s ceiling, the second hall columns prop up the ceiling, four in all, arranged in two rows on the same axis as the first hall’s, with a 3 m wide space between them. A minimum of one of the chambers in hall two seems to be in honor of the Maat religion, implying that the other three in this region may have also had a religious role.

There are two parts to the southern half of the temple: western and southern. Six chambers make up the western part, but the southern half’s size (19.5 by 17.2 m) implies it may have acted as another open court. Blue ceramic tiles with gold inlays were seen along the edges in several of these rooms. The 10 chambers in the northern portion of the temple are similar in style to the ten in the southern part.

Bricks inscribed with different inscriptions, such as “the temple of Amun” or “Nebmaatre in the Temple of Amun” suggest the temple was devoted to the Egyptian god Amun. The house of Rejoicing appears to have been built around the temple.

The temple of Malakata has many features in common with other New Kingdom cult temples, including grand halls and religiously themed chambers, but many others are more like storerooms.

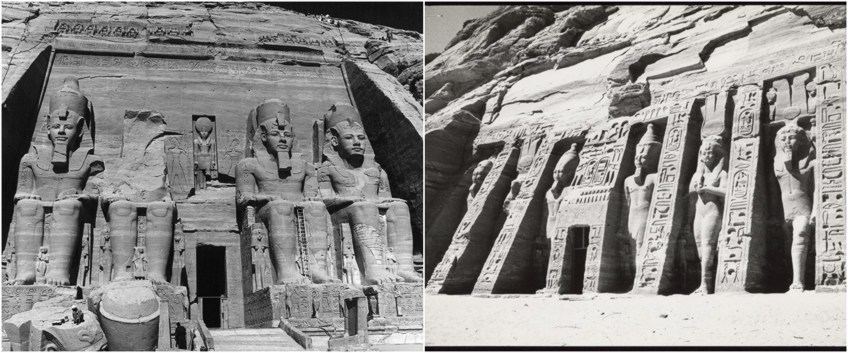

Abu Simbel Temples (1264 BCE)

| Location of Structure | Nubia, Egypt |

| Type of Structure | Temple |

| Period | 1264 BCE |

| Architects | Unknown (c 1264 BC) |

Abu Simbel is a pair of huge rock-cut temples near the Sudanese border in the hamlet of Abu Simbel, Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt. They’re around 230 kilometers (140 miles) southwest of Aswan, on the western shore of Lake Nasser (about 300 km by road). The complex is part of the “Nubian Monuments” UNESCO World Heritage Site, which stretches from Abu Simbel to Philae (near Aswan) and includes Amada, Wadi es-Sebua, and other Nubian monuments.

The twin temples were cut out of the mountainside in the 13th century BC, during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II of the 19th Dynasty. They serve as a permanent memorial to King Ramesses II. His wife Nefertari and children may be seen in tiny figurines near his feet, as they were deemed less important and were not given the same size position. This is a tribute to his victory at the Battle of Kadesh.

Their massive exterior rock relief figures have become widely recognizable.

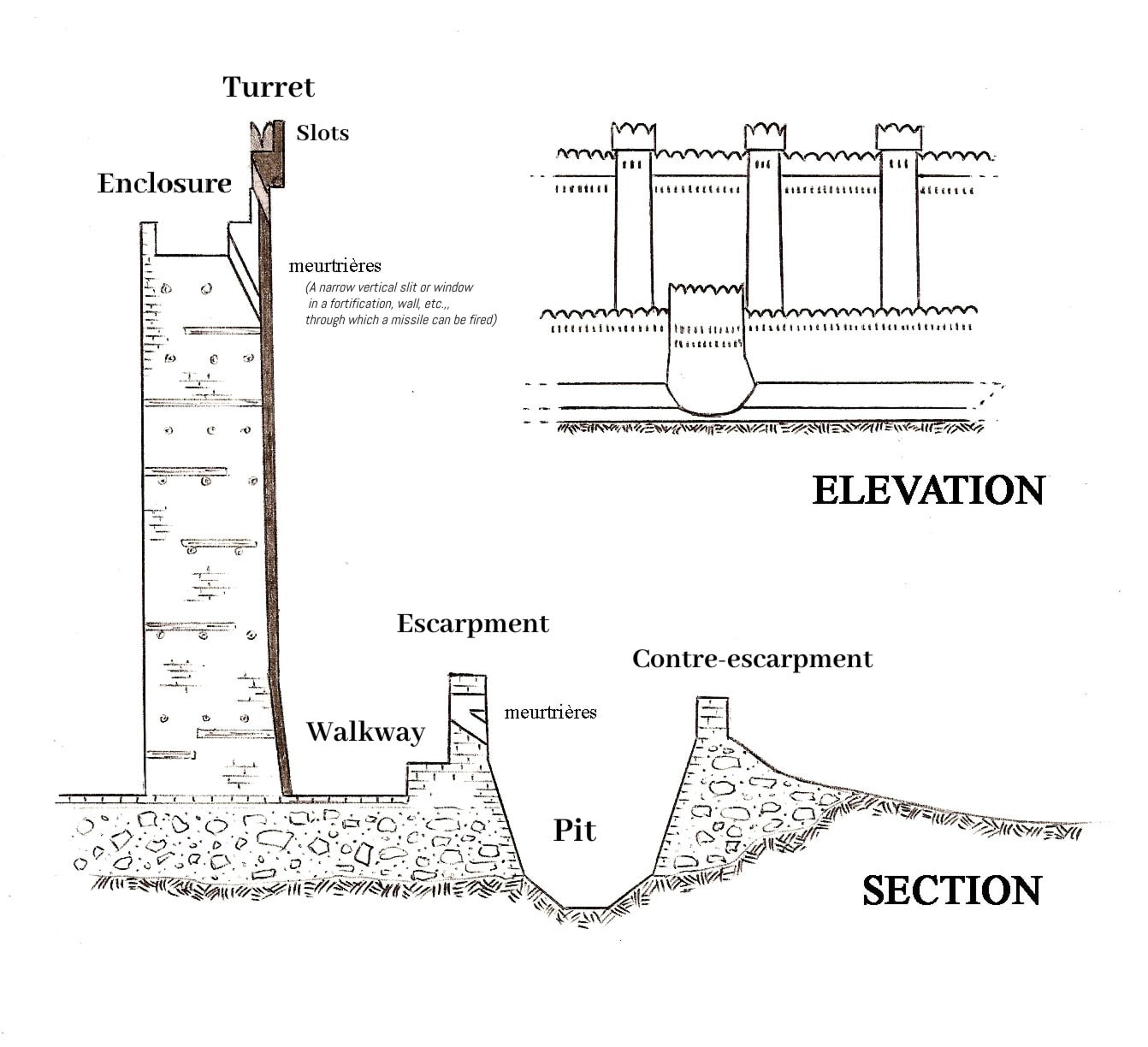

Ancient Egyptian Fortresses

The conflict between opposing kingdoms prompted the construction of fortifications in Ancient Egypt. Nearly all of the castles examined during this time period used the same materials. Only a few Old Kingdom fortifications, like the fort of Buhen, used stone to build their walls. Mudbrick was used for the majority of the walls, although they were strengthened with other materials including lumber.

In addition to the pavement, rocks were used to prevent erosion and maintain them. Secondary walls were constructed outside of the main fortress walls and were close in proximity to one another. As a result, invaders would have difficulty since they would have to demolish this barrier before they could approach the fort’s main walls. If the opponent was able to get through the initial barrier, a different tactic was used. After reaching the main wall, a ditch would be dug between the secondary and first walls.

The goal was to put the adversary in a position where they would be exposed to enemy fire, leaving the invaders vulnerable to arrow fire.

During periods of unification, the position of these ditch walls inside strongholds would become demilitarized, resulting in their demolition. The materials used to build the walls could subsequently be recycled, making the whole concept highly cost-effective.

Ancient Egyptian fortifications served a variety of purposes.

The Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt built fortified outposts along the Nubian River during the Middle Kingdom Period to gain control of the region. Fortresses in Egypt did not always sit along the river. Sites in Egypt and Nubia would be situated on rocky or sandy terrain, respectively. As a result of this tactic, the organization was able to expand its influence throughout the region while also discouraging competing organizations from conducting raids.

Pelusium Fortress (1000 to 800 BC)

| Location of Structure | Nile Delta, Egypt |

| Type of Structure | Fortress |

| Period | 1000 to 800 BC |

| Architects | Unknown (.1000 to 800 BCE) |

The Pelusium stronghold functioned as a defensive fortification against invaders approaching the Nile Delta. Pelusium was also recognized for being a commercial hub, and it performed this purpose for more than a millennium (both maritime and land). Egypt and the Levant were the primary trading partners. While there is no definite information on the fortress’s construction, it is thought that Pelusium was built during the Middle Kingdom era or during the Saite and Persian periods in the 16th and 18th centuries.

Pelusium is also perceived as a significant part of the Nile since more remains have been unearthed outside of its boundaries, indicating that the area was heavily inhabited.

The architectural features of Pelusium (such as its towers and gates) appear to be constructed of limestone. A rising industry in metal is also supposed to have been in this area as a result of the discovery of copper ore. During excavations at the site, older materials going back to some of the early dynasties were also discovered.

Materials found include basalt, granite, diorite, marble, and quartzite. Because the stronghold was built so near to the Nile River, it was encircled by both dunes and coastal lines.

The decline of the Pelusium stronghold was caused by a variety of factors. During the period of its heyday, the Bubonic Plague first emerged in the Mediterranean region, and several fires broke out in the stronghold. Conquest by the Persians, as well as a decline in commerce, might possibly be related to the rise, which could have resulted in an increase in desertion.

Officially, natural causes such as tectonic movements caused Pelusium to disintegrate. The site’s formal abandonment is dated to the time of the Crusades.

Fortress of Jaffa (c. 1460 to 1125 B.C.E)

| Location of Structure | Tel Yafo, ancient Yapu |

| Type of Structure | Fortress |

| Period | c. 1460 to 1125 B.C.E |

| Architects | Unknown (c. 1460 to 1125 B.C.E) |

During Egypt’s New Kingdom period, Jaffa Fortress was significant. It functioned as a fortification as well as the Mediterranean coast’s port. Jaffa is still an important Egyptian port today. The location was formerly under the sovereignty of the Canaanites before falling under the rule of the Egyptian Empire.

It is unknown what exactly triggered the transition from Canaanite to Egyptian occupation due to a paucity of evidence. The fortress was effective in containing the campaigns from Pharaohs of the 18th dynasty during the Late Bronze Age.

In terms of functionality, the site served several purposes. According to legend, the fortress’ principal role was to serve as a storehouse for the army of Egypt.

Rameses gate, which dates from the Late Bronze Age, connects to the fortress. Along with the fortress, ramparts were unearthed. Upon excavation, the site included several artifacts like bowls, imported jars, pot stands, beer, and bread, emphasizing the significance of these goods to the area. The finding of these artifacts demonstrates a strong relationship between food storage and the manufacture of ceramic things.

Other Types of Egyptian Architecture

We have covered the massive popular Egyptian structures up to now. However, the Egyptians built many types of structures that were important in their lives. Now we will look at the burial tombs and ancient gardens of the Egyptians.

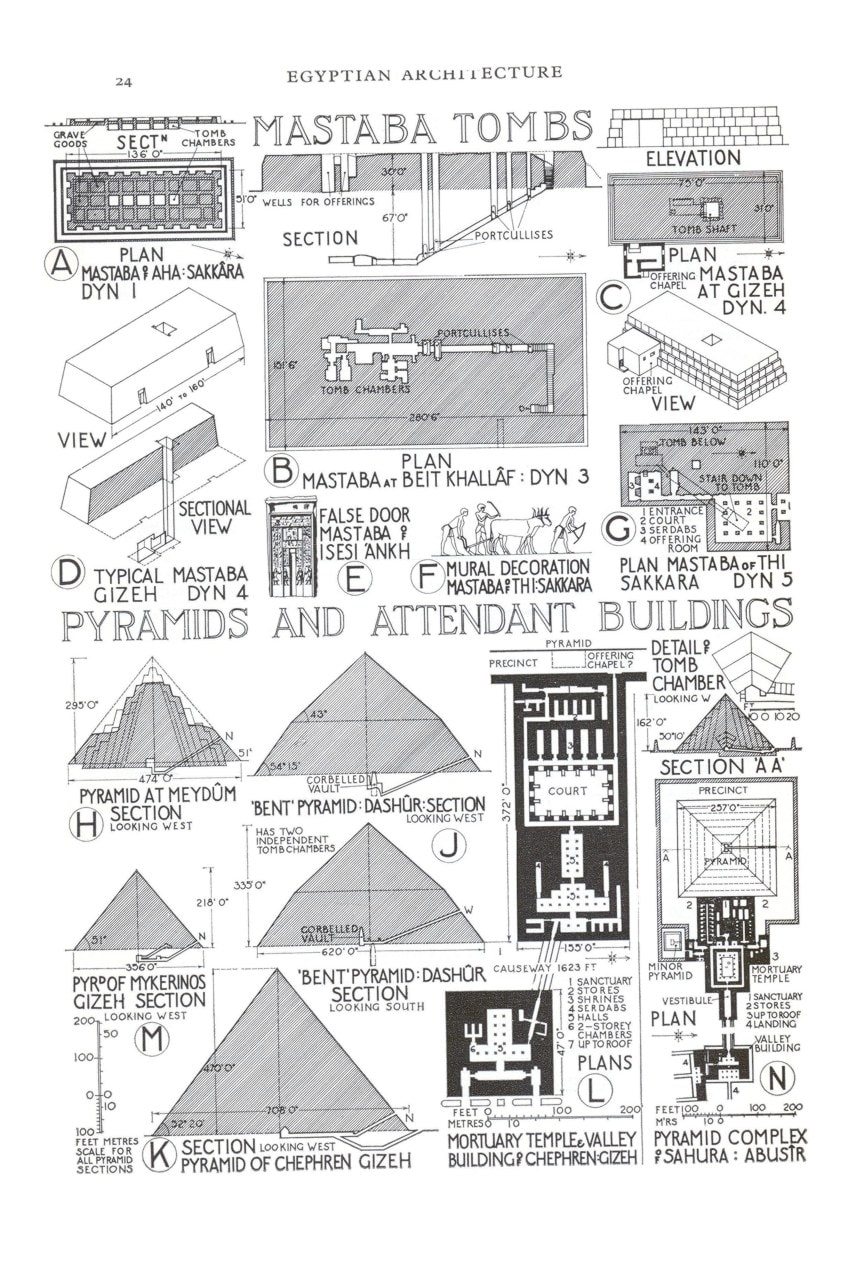

Mastabas

Mastabas are royally significant burial tombs. Many of the tombs discovered throughout history were chosen by Egyptian kings to be situated near the Nile River. The structural exterior of Mastabas has changed over time, although there has been a visible progression during the duration of Egyptian dynasties. The First Egyptian Dynasty’s mastabas would be built of stepped bricks. By the Fourth Dynasty, the design had evolved as the structural outside changed from brick to stone.

The motivation behind mastabas’ stepped designs is linked to the concept of “accession.”

A major concern when building a tomb was the ability to penetrate laterally. To safeguard the structure’s base from damage, brickwork layers were built around it. The ancient empire’s mastabas were erected in the shape of a pyramid. This method of burial was primarily reserved for rulers, such as the monarch and his family.

Other characteristics of mastabas from the old empire include rectangular forms, sloping stone and brick walls, and a building axis that runs both north and south. The inside of the mastabas is divided into many sections, including an offering area, memorial sculptures, and a vault beneath which sarcophagi were kept. These burials were no longer used by the time Empire ended

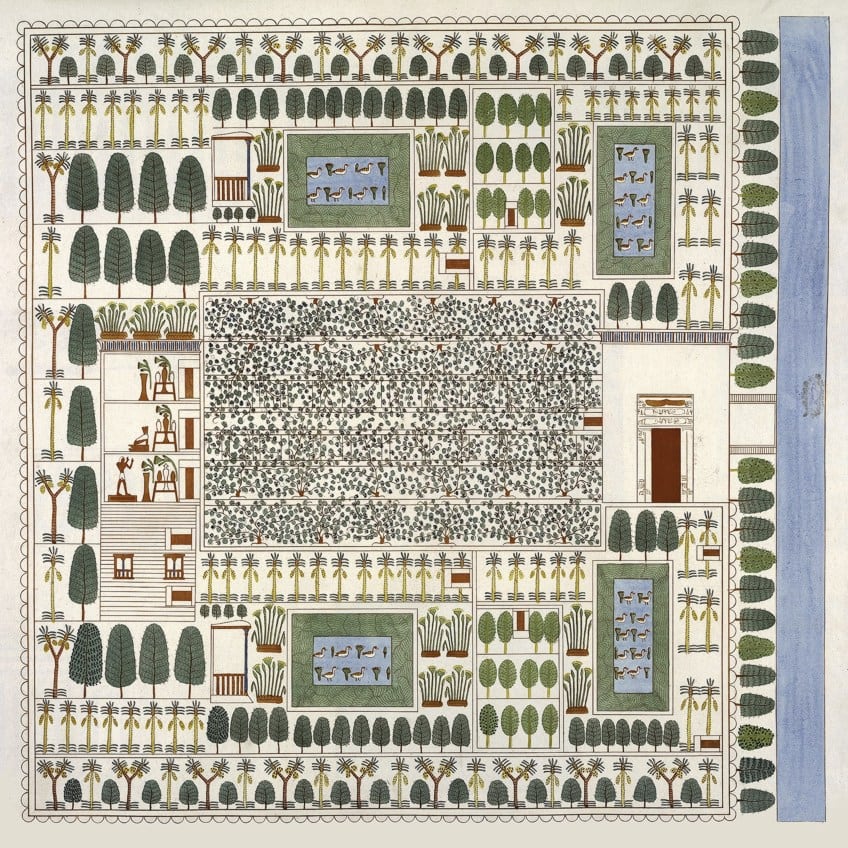

Gardens

Temple gardens, private gardens, and food gardens are the three types of gardens that have been documented in ancient Egypt. Some temples, like those at Deir el-Bahri, included groves and trees, including the holy Ished Tree (Persea). Private pleasure gardens may be seen in a Meketra tomb model from the 11th Dynasty and in New Kingdom tomb ornamentation.

They were usually encircled by a high wall, with trees and flowers planted and shaded spaces provided. Plants were grown for their fruit and aroma.

Cornflowers, poppies, and daisies were common flowers, while the pomegranate, which was first cultivated in the New Kingdom, quickly became a beloved shrub. In the estate grounds of the well-to-do, a decorative pool was used to keep fish, ducks, and water lilies. Private or temple-owned vegetable plots were split into squares by water canals and placed near the Nile. They were watered either by hand or, starting in the late 18th Dynasty, by the shaduf.

Today we have learned about the fascinating world of ancient Egyptian architecture. The history of ancient Egypt was not one of a single, long-lasting civilization, but one marked by instability after upheaval. Scholars have split the history of the region into several periods. Egyptian architecture is no exception. Instead of a single style, there were a variety of styles that emerged over different historical periods but shared some traits.

Frequently Asked Questions:

What Were Pyramid Buildings and Egyptian Buildings Made From?

Because wood was scarce in ancient Egypt, the most prevalent construction material was baked mud and stone brick. Granite and sandstone, as well as limestone, were prominent building materials. Bricks were commonly employed for town and fortification structures, whereas stone was reserved mostly for temples and cemeteries. Local quarries and gravel, sand, and mud bricks were used to construct the pyramid structures’ interior.

What Are the Most Well-Known Buildings of Egyptian Architecture?

The Egyptian buildings of the Giza complex are the most famous example of Egyptian architecture. They are iconic symbols of a long-gone era of Pharaohs. The pyramids and the Great Sphinx are especially recognized around the world as ancient wonders that still deserve to be admired and explored. The magnificence and wonder of these huge Egyptian monuments still stir the imaginations of scholars and the public.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Egyptian Architecture – The Greatest Egyptian Monuments and Buildings.” Art in Context. October 9, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/egyptian-architecture/

van Huyssteen, J. (2021, 9 October). Egyptian Architecture – The Greatest Egyptian Monuments and Buildings. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/egyptian-architecture/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Egyptian Architecture – The Greatest Egyptian Monuments and Buildings.” Art in Context, October 9, 2021. https://artincontext.org/egyptian-architecture/.