Claude Cahun – A Look at Claude Cahun’s Life and Artistic Contribution

Claude Cahun’s self-portraits are a dazzling, whirling blend of mystique, exhilaration, and solemnity. Claude Cahun’s life began as Lucy Schwob, but she later reclassified herself as gender-neutral. Following Cahun’s arrest and ensuing incarceration for resisting the Nazis, most of Claude Cahun’s artwork was destroyed.

Claude Cahun’s Life and Art

| Nationality | French |

| Date of Birth | 25 October 1894 |

| Date of Death | 8 December 1954 |

| Place of Birth | Nantes, France |

Claude Cahun spent much of her time in New Jersey with Marcel Moore, her long-term love. They acquired their chosen gender-neutral monikers, Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe, when they were young adults.

Moore, despite her invisibility, was constantly present – usually shooting pictures and also creating collages – and was as much an artist companion as Cahun’s emotional support in this respect.

Childhood

In 1894, Claude Cahun was originally born as Lucy Schwob to a Jewish household in Nantes, France. Lucy Schwob eventually changed her name to Claude Cahun to be gender-neutral as a creator and author. Marcel Schwob, Lucy’s uncle, was a well-known Symbolist author. Marcel Schwob was well-known in Paris and became a personal confidant of Oscar Wilde.

David Leon Cahun, Cahun’s grandfather, was also an influential intelligent character from the Orientalist group, therefore the artist was steeped in an intellectual and artistic milieu from a young age.

Cahun’s mother struggled with severe mental illness and was institutionalized, so Cahun was raised primarily by their blind grandmother. Cahun was moved to boarding school in Surrey, England for a brief time due to his mother’s health and an anti-semitic event at school in France. Cahun struggled from bulimia, thoughts of suicide, and periods of crippling sadness as a teenager, just like her mother. Fortunately, it was also about this period that Cahun met her future partner in life, Suzanne Malherbe.

This meeting was later described by Cahun as a “thunderbolt collision,” and their friendship became one of the most important forming aspects of Claude Cahun’s life and work. Cahun’s father married Malherbe’s mother later in life, which meant they were now stepsisters.

Despite this, Cahun and Malherbe fell in love and relocated to Paris in 1919, during the height of the Dada period, when they acquired the gender-neutral identities of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore.

Early Training and Career

Of course, the couple’s attempts at gender-neutrality were immensely contentious, but Moore and Cahun began to link themselves with the tiny circle of Parisian avant-garde individuals who were also playing with identity at the time. Around 1920, Marcel Duchamp debuted his female alter-ego, Rrose Selavy, as an artistic character. Cahun and Moore, on the other hand, chose new names not to change gender, but to avoid such opposing created linkages entirely. While in Paris, Cahun pursued philosophy and literature at the Sorbonne.

Moore and Cahun began organizing salons and parties at their house about 1922, welcoming avant-garde artists and writers.

Although Cahun had been fascinated with shooting and self-portraiture from the age of 12, it wasn’t until the 1920s that she started to explore actively with the technique, producing some of the most captivating and iconic photos. Cahun was on the outskirts of the Surrealist group at the time but was not intimately associated with it.

Moore and Cahun also met Pierre Albert-Birot, the head of Le Plateau, the experimental theatre, where Cahun performed and Moore developed stage costumes and sets. Cahun concentrated on writing as well as photography throughout the 1920s.

Cahun authored the novel “Heroines” in 1925, as well as “Aveux Non-Avenus”, a compendium of texts and photo collages, in a special edition of 500 copies.

Mature Period

Throughout the 1930s, Cahun got more involved in politics with Moore, and the two of them condemned the growth of fascism in Europe. Cahun joined an association of ‘revolutionary’ artists in 1932 when she encountered one of the Surrealist movement’s founders, Andre Breton.

Cahun gave Breton a copy of “Aveux Non-Avenus” on their first encounter, and the experimental wording struck him. They became friends, and Breton once referred to Cahun as “one of our time’s most intriguing souls.”

Cahun’s texts, created in conjunction with Moore, wowed other major participants of the Surrealist movement, including Robert Desnos, René Crevel, and Henri Michaux, the poet and painter with whom Cahun visited in a mental institution. These contacts sparked a tighter relationship with the Surrealists, and Cahun began to show work alongside them, notably at significant Surrealist exhibits in Paris and London in 1936.

In terms of politics, the Surrealists and the French Communist Party broke in 1935, and Cahun and Moore stayed on the side of Georges Bataille and Breton as they sought to utilize art to halt the flow of war. Breton, in particular, urged Cahun to write a reply to Louis Aragon, who had abandoned Surrealism in favor of Communism. Cahun’s book, The Bets are Open, criticizes Aragon’s views and supports a sort of art that spreads its ideas through “indirect action” instead of propaganda. The pair then relocated to La Rocquaise, a mansion on Jersey, a British territory sandwiched between France and England, in 1937.

Despite the fact that the two continued to make work (both photography and literary), they had little interaction with the outside world after this, thus ending Cahun’s involvement in the Surrealist movement.

At this time the couple began to use their birth names, to the rest of Jersey’s residents, they gained the title “Les mesdames” earning ill-repute for their odd behavior such as wearing trousers and walking their cat on a leash.

Legacy

Claude Cahun’s artistic output, several personae, and odd personal life have made her a source of inspiration and fascination for many subsequent artists. Cahun is relevant to both homosexual activists and feminists because of her gender-shifting self-presentation and non-heterosexual connection.

Claude Cahun’s self-portraiture also heralds the beginnings of a crucial new tendency among non-male creatives. Cahun’s technique draws into an artist’s urge to investigate the intersections of sexuality, gender, and power.

Claude Cahun’s photography has also influenced celebrities who are breaking down gender stereotypes, such as David Bowie. Claude Cahun’s art was featured in a Bowie show in New York in 2007. Talking about Cahun, Bowie stated: “You might call her subversive, or a cross-dressing Man Ray with surrealist inclinations. In the kindest possible sense, I find this work very insane. Outside of the United Kingdom and France, she has not received the credit she deserves as a founder and friend of the Surrealist group.”

Claude Cahun’s Photography Style

Cahun’s work is infused with themes of sorrow, hopelessness, and uncertainty. Cahun does not create “complete” works; instead, all of the pictures and words merge to form a larger, though unfinished total. Cahun admits to not knowing the answers and, as a result, uncommonly exposes the rawness, pain, and anguish of not knowing. The opening statement of André Breton’s book Nadja (1928), “Who Am I?” is repeated with vigor, while collages constructed with Moore demonstrate the same love of harmony and kaleidoscopic vision seen in the book’s pictures.

Cahun, like other female Surrealists, is interested in specific themes such as hair, fingers, and animal companions, and she utilizes methods of duplication and reflections to bring into question established concepts of gender. Cahun’s art is reminiscent of Cindy Sherman’s, Francesca Woodman’s, and Gillian Wearing’s.

Sherman and Wearing, both influenced by Cahun’s theatrical works, subsequently investigate the assumption of multiple masked personas, referencing Joan Rivière’s famous dissertation on women who use “womanliness as masquerade” (1929). Woodman, on the other hand, continued from Cahun’s later, more naturalistic outdoor photos. Both painters masterfully integrate eros and Thanatos in the great background of nature, entangled by seaweed, wrapped in foliage, and immersed in water.

Claude Cahun’s Photography

Cahun is shrouded in mystery, making the artist a lonely figure. Cahun was an obsessive loner in nature, but he was also inextricably linked to Moore. Moving away from the creative circles of Paris to the secluded island of Jersey in 1937, the couple became uncomfortable, alienated, and unreachable.

Furthermore, with most of Cahun’s work lost in 1944, the entire recognized oeuvre shrank, deepening the mystery. The original works that have survived are modest, as though they were left as hints for a much larger treasure hunt.

Self Portrait as a Young Girl (1914)

| Date of Creation | 1914 |

| Medium | Photographic Print |

| Dimensions | unknown |

| Current Location | Jersey Heritage Collections |

This shot is one of Cahun’s first known instances of a self-portrait and has a deep and piercing outer look. The artist’s head is noticeably and unsettlingly disembodied, implying an imbalance as if the head is excessively weighty and the body is strangely superfluous. Art Historian Sarah Howgate, who specializes in Cahun’s works, believes that “she seems like a patient in a hospital cot” and suggests that this might be a visual reference to Cahun’s and her mother’s moments of their great depression. This line of inquiry can be pursued further, as the woman looks to be dead in a mortuary.

Cahun’s eyes are widely opened and certainly alive, despite her seeming death, maybe because she is continually burdened by inside awareness of the deeper and more secret parts of existence.

The artist’s copious flowing locks have a life of their own and immediately remind one of Medusa, the Greek mythological and powerful woman with a head full of snakes and a glance that could turn men to stone. This reading makes it apparent that Cahun had no desire to satisfy men, as was common at the period.

Instead, the artist pushes and questions the audience, recognizing the feeling of feminine wrath that cultures and people still struggle to express today.

Cahun is in bed, yet she is neither asleep, convalescing, or sexually receptive as one might expect for a woman in 1914. Rather, the impression is likely to be a combination of a depressed, enraged, and energetic artist, all of which was inconceivable for a woman at the time and continue to be difficulties now.

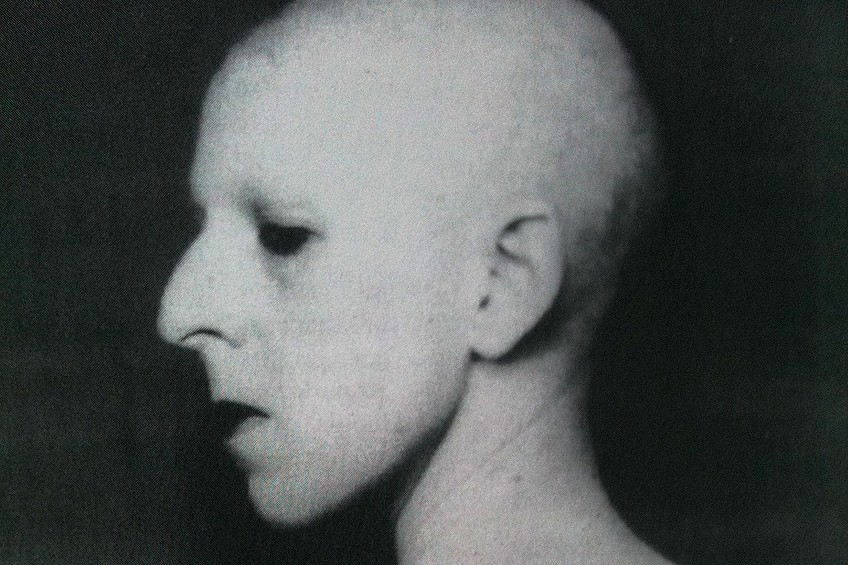

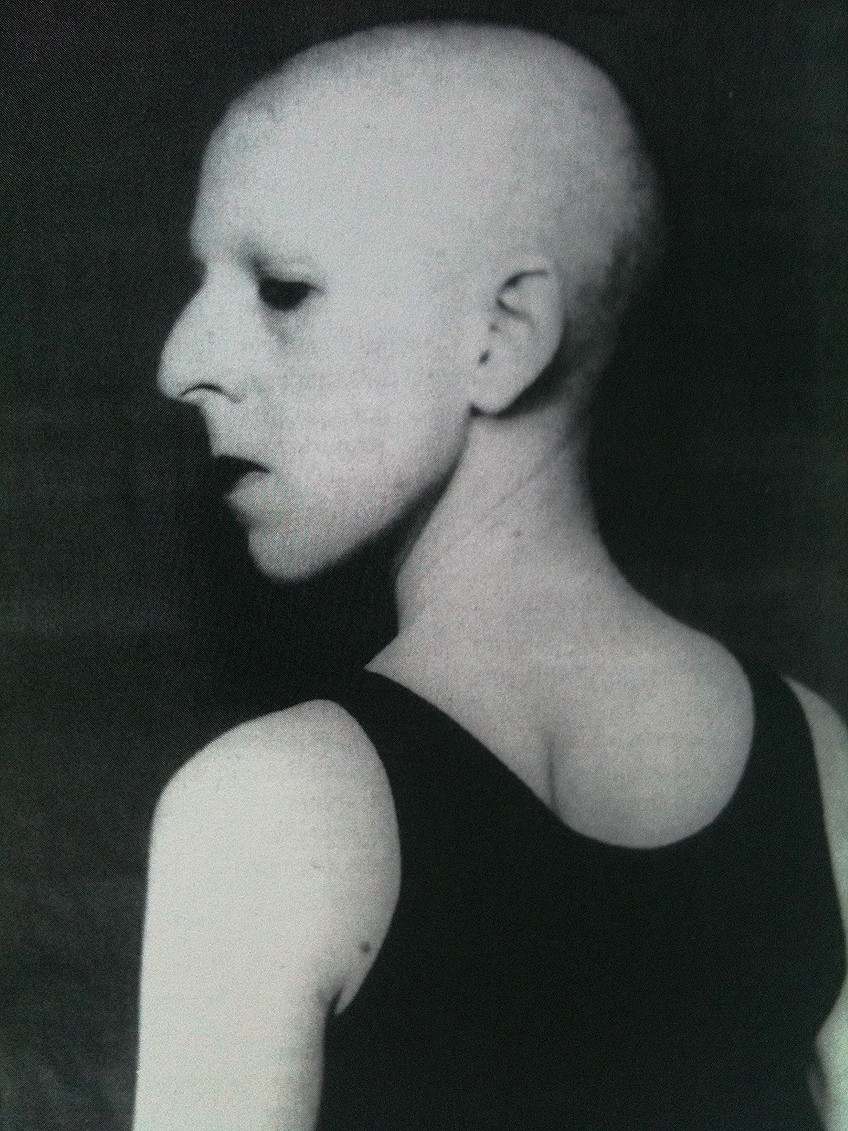

Self Portrait, Head Between Hands (1920)

| Date of Creation | 1920 |

| Medium | Photographic Print |

| Dimensions | unknown |

| Current Location | Jersey Heritage Collections |

In this beautiful portrait, the artist has progressed from Lucy Schwob’s childhood/adolescent identity to the gender-neutral character of Claude Cahun. The long hair has been replaced with a shaved head, removing the usual attraction linkages created between ladies and their flowing tresses. The bald picture is one of a series created that year. This rendition is inspired by Edvard Munch’s existential painting The Scream (1893), while another shows Cahun hand on hip clothed in a man’s attire, and a third hairless image shows the creator cross-legged in profile sitting in a monk-like stance.

All three photographs provide a vision of gender-neutrality that, because they were created while Cahun was engaged in a vibrant Parisian lesbian avant-garde society, aptly represent Cahun’s personal experience at the time. Furthermore, it is worth noting that throughout postwar Europe, there is a general rethinking of gender constructs.

This was certainly the case for Frida Kahlo, who frequently donned a man’s suit in family portraits during the 1920s until painting Self Portrait with Cropped Hair in 1940. In contrast to Munch’s extremely expressive face, Cahun seems to have an appearance of remoteness and an overall lack of feeling. Therefore, the creator’s hands are placed on each side of a vacant face not just to recall the immediacy of a lived event like The Scream, but also to give the impression that Cahun is wearing a mask.

Cahun’s use of masks in his artworks is influenced by his engagement in modern experimental theater, Dada representation, and a general fascination with African art. Picasso explores the mask motif as early as 1905 when he shows Gertrude Stein, the lesbian writer at the heart of early-20th-century Parisian salon society, infusing her appearance with eternal gravity and gender expression. As such, the mask alluded to the hidden dimensions of individuality that society conformity frequently rejects.

Cahun accepts this metaphor and appears to be referring to recent theoretical discourses that link masks to one’s everyday acceptance/rejection of identity and gender performances. The shot, however, is more than just a commentary on changing gender politics. The picture, of a Jewish person with a visibly stripped-down personality made sexless by hair removal, foretells the Holocaust’s horrific crimes in an unsettling way. In addition, it consistently condemns past, current, and future maltreatment to be suffered by women who were ‘different.’

For instance, people classified as ‘witches’ in the 16th century or ladies who accepted German partners during World War II were all obliged to shave their offensive hair as a “penalty” for what was in actuality free living.

I Am In Training Don’t Kiss Me (1927)

| Date of Creation | 1927 |

| Medium | Photographic Print |

| Dimensions | unknown |

| Current Location | Jersey Heritage Collections |

Unlike her previous works, Cahun provides an evidently conceived personality in this and other images from the late 1920s, using props, highly stylized garments, and make-up. The shot is part of a series in which Cahun adopts the contradictory portrayal of a feminized strongman and executes numerous stances in that capacity. Cahun uses this identity to mix feminine and masculine stereotypes. Cahun is holding attractively painted weights, pseudo-nipples are sewed into the flat costume shirt, and even the conventional weight-lifter facial hair has been moved onto the short hair curls.

The English lettering on Cahun’s breast reads, “I am in training, don’t kiss me,” with coquettishly pursed lips.

With a flirtatious and tempting glance, it is also disdainful and condescending, insulting the spectator for being drawn to what is clearly not on offer. The strongman series’ theatrical nature blends contradicting conceptions of gender to show the intriguing area of identity slippage between opposite poles.

Indeed, not long after this shot was taken, in 1929, Cahun published essays in publications outlining controversial notions introducing the potential of a third sex, integrating masculine and feminine qualities but existing as neither. Cahun’s experimentation with constructed identity, which was discovered and documented by François Leperlier, the art historian, in 1994, set the stage for a post-modern performative feeling. The elaborately staged images anticipate Cindy Sherman’s identity-shifting self-portrait pictures and Gillian Wearing’s more recent masks work.

Cahun’s works are a result of their creative and social surroundings, but they also deal with age-old concerns of identity.

During the Roaring 20s, when feminism, including suffrage, was spreading across the United States and most of Europe, the notion of the “New Woman” arose with intensity. Cahun, as part of but also independent from this historical era, breaks down gender barriers and displays oneself merely as an energetic individual rather than as a woman or man characterized by their sex.

Today we have discovered the art and life of Claude Cahun. Claude Cahun’s self-portraits blurred the lines of gender and identity. Claude Cahun’s photography had a significant impact on photography, influencing current photographers such as Gillian Wearing, Cindy Sherman, and Nan Goldin.

Take a look at our Claude Cahun art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Claude Cahun?

Surrealist photographer Claude Cahun’s work focused on gender identification and the unconscious psyche. The artist’s 1928 self-portrait encapsulates her mentality and manner, as she glances boldly at the camera in an ensemble that is neither feminine nor masculine in appearance. Her first known self-portraits come from 1912 when she was around 18 years old. She changed her name to the gender-neutral Claude Cahun in the early 1920s, making it the artist’s third and last name change. She relocated to Paris with her step-sister and lover, Marcel Moor, and became immersed in the Surrealist art movement.

What Photography Did Claude Cahun Create?

Themes of grief, helplessness, and uncertainty run through Cahun’s work. Cahun does not make so-called complete works, rather, all of the images and phrases are combined to form a greater, incomplete whole. Cahun recognizes that she doesn’t have the answers and, as a result, she exposes the rawness, grief, and misery of not knowing in an unusual way. Cahun, like other female Surrealists, is fascinated by specific subjects like hair, fingers, and animal companions, and she employs duplication and reflection techniques to call into question gender stereotypes.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Claude Cahun – A Look at Claude Cahun’s Life and Artistic Contribution.” Art in Context. April 26, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/claude-cahun/

Meyer, I. (2022, 26 April). Claude Cahun – A Look at Claude Cahun’s Life and Artistic Contribution. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/claude-cahun/

Meyer, Isabella. “Claude Cahun – A Look at Claude Cahun’s Life and Artistic Contribution.” Art in Context, April 26, 2022. https://artincontext.org/claude-cahun/.