Art Nouveau Paintings – A Look at the Art Nouveau Style of Art

Art Nouveau artworks were part of a revolutionary global movement of contemporary art that was popular from 1890 until World War One. It arose in response to 19th-century aesthetics influenced by ideology in principle and neoclassicism specifically, and it promoted the concept of visual art as a normal part of life. Artists should no longer disregard any common item, no matter how utilitarian it may be. This approach was seen to be highly revolutionary and novel, therefore its name signifying new Art Nouveau styles.

Table of Contents

- 1 Art Nouveau Characteristics

- 2 Famous Art Nouveau Paintings

- 2.1 Wren’s City Churches (1883) by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo

- 2.2 At the Moulin Rouge (c. 1892) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

- 2.3 The Peacock Skirt (1893) by Aubrey Beardsley

- 2.4 The Dancer’s Reward (1894) by Aubrey Beardsley

- 2.5 Gismonda (1894) by Alphonse Mucha

- 2.6 The May Queen (1900) by Margaret Macdonald

- 2.7 Beethoven Frieze (1902) by Gustav Klimt

- 2.8 The Kiss (1908) by Gustav Klimt

- 2.9 The Slavs in Their Homeland (1928) by Alphonse Mucha

- 2.10 Les Femmes Fatales (1933) by Gerda Wegener

- 3 Frequently Asked Questions

Art Nouveau Characteristics

Art Nouveau is commonly seen as a “style” instead of an ideology: yet, it was inspired by unique concepts rather than merely imaginative aspirations. All of the greatest reliable Art Nouveau creatives shared a commitment to press further than the boundaries of neoclassicism – that overstated consideration with concepts of history that characterize the majority of 19th-century styling: they wanted a new visual style in a raw assessment of the purpose and a close investigation of the organic world.

Art Nouveau’s characteristics are difficult to identify, although the following are differentiating aspects.

The Art Nouveau concept advocated for the application of aesthetic designs to ordinary goods in order to make attractive things accessible to all. Nothing was too mundane to be “beautified.” In essence, Art Nouveau perceived no distinction between fine art (paintings and sculptures) and practical or fine art (ceramics, and other practical things such as furniture).

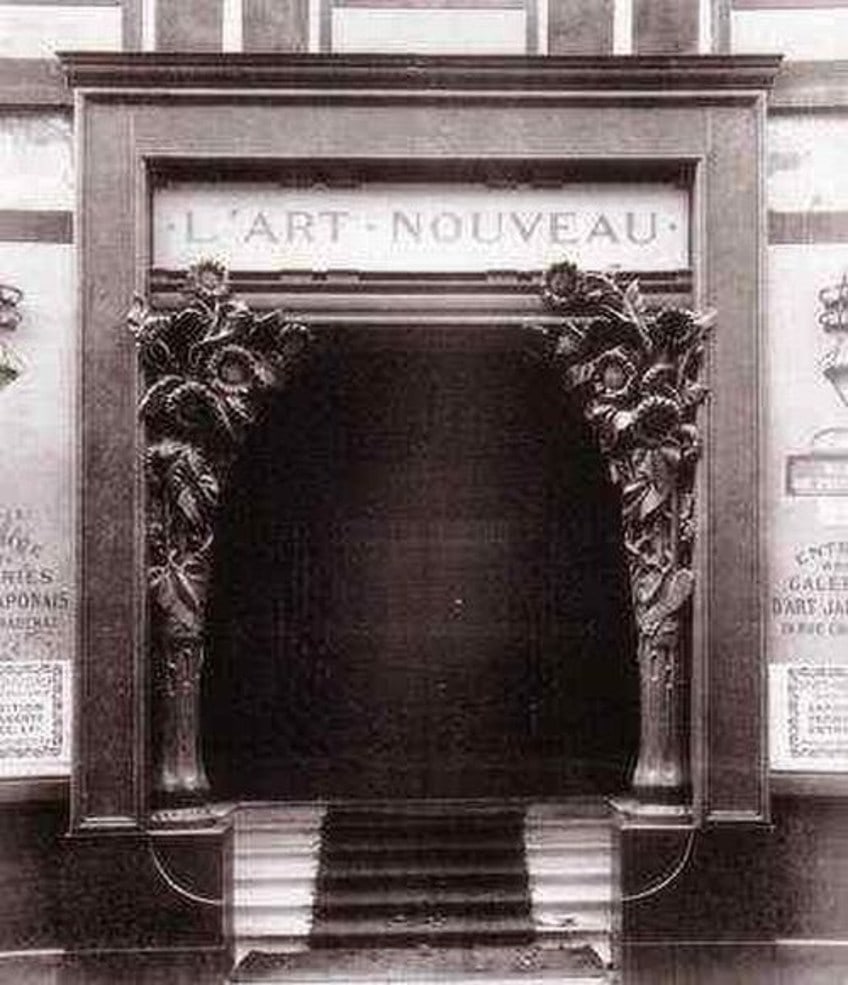

The aesthetic was a response to an art world characterized by the rigid symmetry of Neoclassical designs. The La Maison de l’Art Nouveau was an art gallery in France that was a famed outlet of French Art Nouveau and where the movement adopted its name from.

Famous Art Nouveau Paintings

To get a better understanding of Art Nouveau’s Characteristics, we can explore some of the most well-known Art Nouveau paintings. This list will include some outstanding examples of Art Nouveau portraits as well as introduce us to a notable Art Nouveau woman or two, as both model and painter. These pieces represent the variety and magnificence of the various Art Nouveau styles.

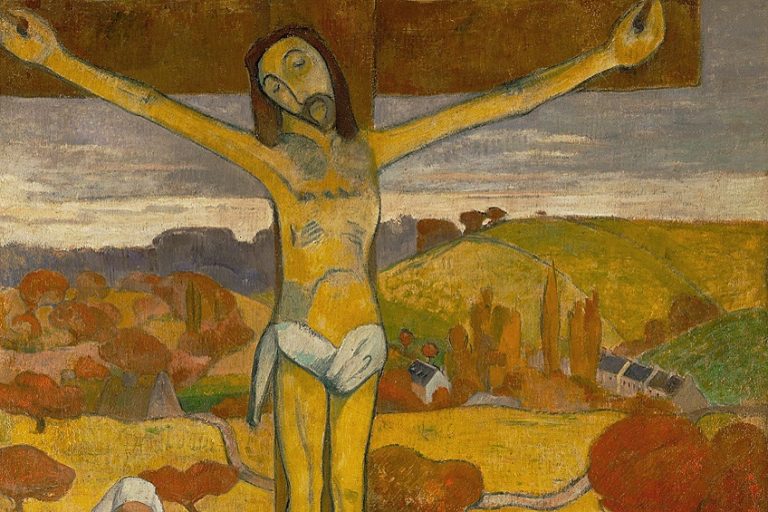

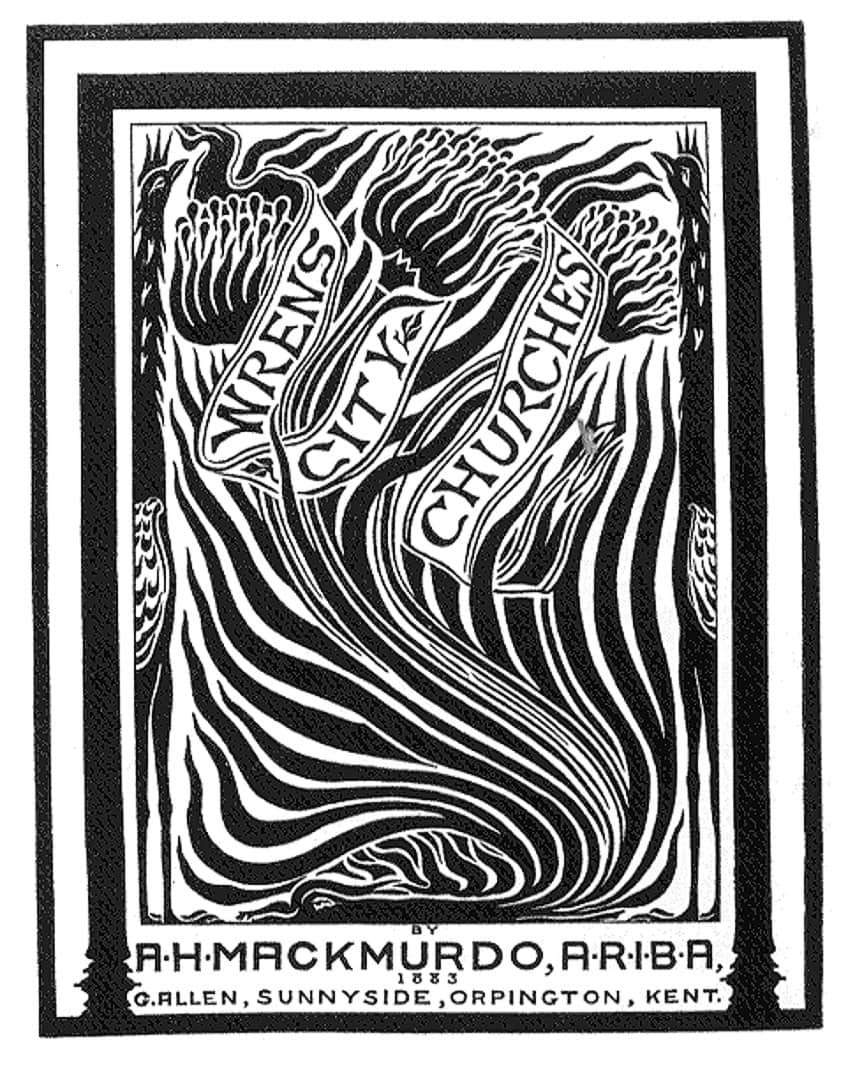

Wren’s City Churches (1883) by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo

| Date Completed | 1883 |

| Medium | Woodcut on handmade Paper |

| Dimensions | 29 cm x 23 cm |

| Currently Located | Dallas Museum of Art |

Wren’s City Churches by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo demonstrates the impact of English style on the Art Nouveau styles in Europe. The title page has intricate interactions of negative and positive space, graphic patterns, and abstracted patterns derived from biological plant development. Although there are sporadic instances of English proto-Art Nouveau patterns in Art Nouveau history, Mackmurdo’s ideas for furnishings, tapestries, and publications created at the Century Guild between 1882 and 1900 demonstrate the most continuous use of the graphic dynamism intrinsic in Art Nouveau.

John Ruskin, a prominent wellspring of motivation for Pre-Raphaelites, was Mackmurdo’s initial creative influence.

Mackmurdo studied the principles of Pre-Raphaelite style from William Morris, who persuaded him to form the Century Guild in 1882 alongside Herbert Home, Clement Heaton, George Esling, and others. The Hobby Horse, which later became the group’s authorized publication, served as a venue for debating the Arts and Crafts philosophy and published instances of its creations.

Because the guild’s activity was collaborative, it might be hard to separate individual efforts. Mackmurdo transforms the white, empty space surrounding the dark shapes into active elements of the image plane by twisting the stems into strange, whiplashed patterns.

In comparison, William Morris’ common early style sets a well-specified, optically consistent pattern on top of a colorful backdrop, accentuating the foreground while ignoring the backdrop.

Moreover, although Morris’ wallpaper patterns are often divided into symmetric parts that line along a vertical or horizontal plane, Mackmurdo’s are strongly related to the irregularity of Japanese arrangements.

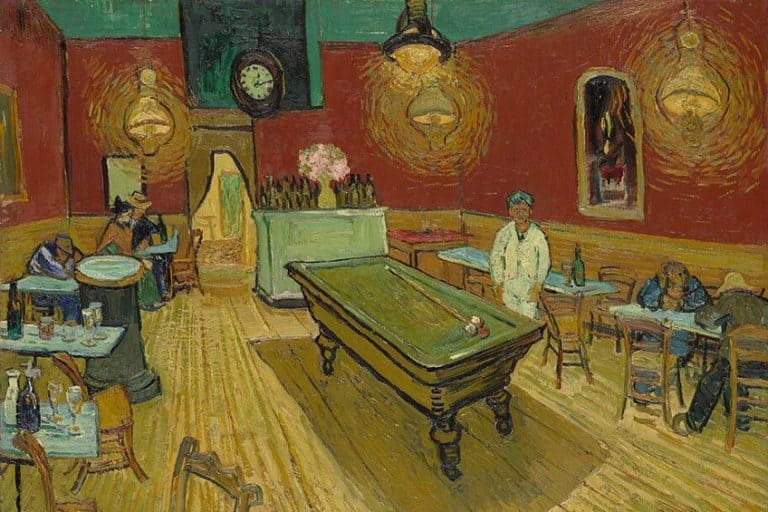

At the Moulin Rouge (c. 1892) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

| Date Completed | c. 1892 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 115 cm x 149 cm |

| Currently Located | Art Institute of Chicago |

Toulouse-Lautrec produced one of his greatest pieces, At the Moulin Rouge, while residing in Montmartre, Paris, located close to the actual famous club. Viewers of the artwork will notice how the artist was able to add several well-known figures of the period. A booth on the cabaret floor is in the center of the image. A small number of males and females are seated around the table.

Among them are well-known entertainers, photographers, and authors.

The Art Nouveau woman with ginger hair is also seated with the gathering at the booth, which serves as its main focal point. The female figure is Jane Avril, a well-known performer. He frequented the Moulin Rouge since it was near to Toulouse-painting Lautrec’s workshop.

The establishment was one of Montmartre’s most well-known cabarets. It was a hangout for his favorite artists and his associates. He managed to portray them, as well as the place, in his works by using his talents of perception. He created a number of works related to the Moulin Rouge.

He used color to contribute to the ambiance, but he also used varied lines to contribute to the graphic intensity. In images such as the silhouette of a performer straightening her hair, he employs curves. This is in juxtaposition to his use of strong diagonal lines from the railing and floors.

Using this method, as well as color, he conveys to the visitor the mood of the Moulin Rouge.

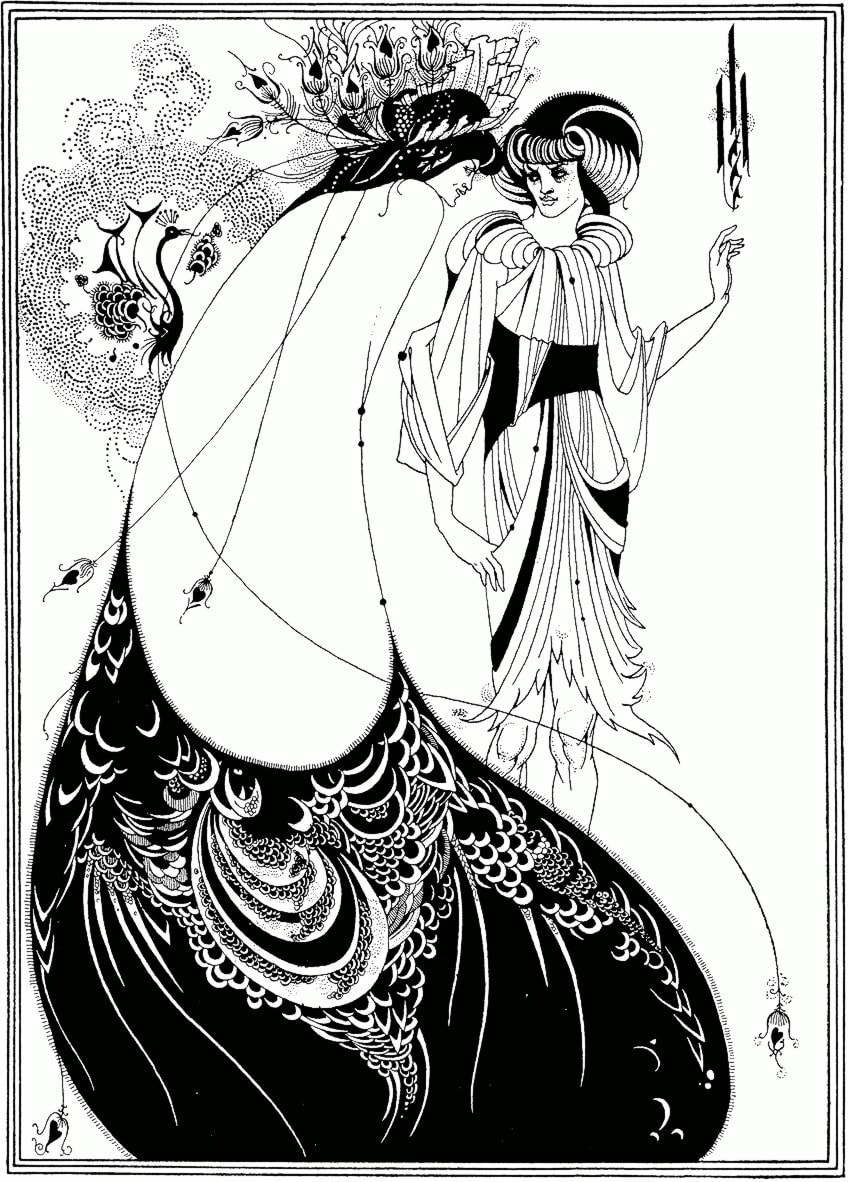

The Peacock Skirt (1893) by Aubrey Beardsley

| Date Completed | 1893 |

| Medium | Pen and Ink Drawing |

| Dimensions | 178 mm x 127 mm |

| Currently Located | Harvard Art Museum |

Aubrey Beardsley created The Peacock Skirt in 1893. In 1894, the first English publication of Oscar Wilde’s drama Salome included a woodblock print of his initial pen and ink sketch. Salome was penned in French in 1891 when Wilde was residing in Paris. The story’s presentation was outlawed in England, reportedly because it included biblical figures.

Prohibited for adapting scriptural figures for the theatre, its daring portrayal of feminine eroticism would have astounded the late Victorian elite. Beardsley embodies Wilde’s rebellious approach to gender norms.

Salome is the hunter, and she appears to be heading in for the kill. Her exquisitely frilled and girlish prey, the Scriptural “youthful Syrian,” may well be a lady – until one notices the knees. While Beardsley’s subsequent drawings for the raucous classical comedy Lysistrata didn’t hold back on the sensuality, it’s all inferred here. Those instinctual art nouveau contours, especially the serpentine stalks of the peacock plumes, give a subtle suggestion of the whip, while the tickling quills have a penile character.

Although Wilde later dismissed Beardsley’s sketches as “the filthy scrawls of a foolish youngster,” he first sent him a manuscript of the drama with a message stating that he was the only painter who grasped Salome’s movement.

The Dancer’s Reward (1894) by Aubrey Beardsley

| Date Completed | 1894 |

| Medium | Block Print |

| Dimensions | 34 cm x 27 cm |

| Currently Located | Private Collection |

Beardsley conveys current anxieties about the demise of patriarchal society at the hands of the assertive Modern Feminine in The Dancer’s Reward, in which the performer Salome brags over her beheaded prize, the skull of St John the Baptist. The ambiguous mirroring of John’s and Salome’s visage also suggests gender issues. Beardsley’s duplicating tactics, such as the Nubian arm that serves as a platform, the snaky hair that serves as streams of bloodshed, and the white-collar that suggests a pair of dangling bosom, call into question power. The Dancer’s Reward is a fine example of a Victorian jail illustration.

While some pieces convey a moral viewpoint on the repercussions of wrongdoing, while others depict the horrors of death as decay, Beardsley’s artwork is exaggerated, abstracted, and satirical.

He just suggests, rather than displays, the inmate’s chamber, with the turnkey’s forearm emerging from the subterranean reservoir to present the murdered man’s skull to the performer. Oscar Wilde was dissatisfied with Beardsley’s pictures for his production. Nevertheless, the general populace associated Beardsley with Wilde, and when the screenwriter was detained the very next year for the serious offense of “lewd conduct,” John Lane was compelled not only to lose Wilde from his publications list but furthermore to let Beardsley go as art editor of a small publication known as the Yellow Book.

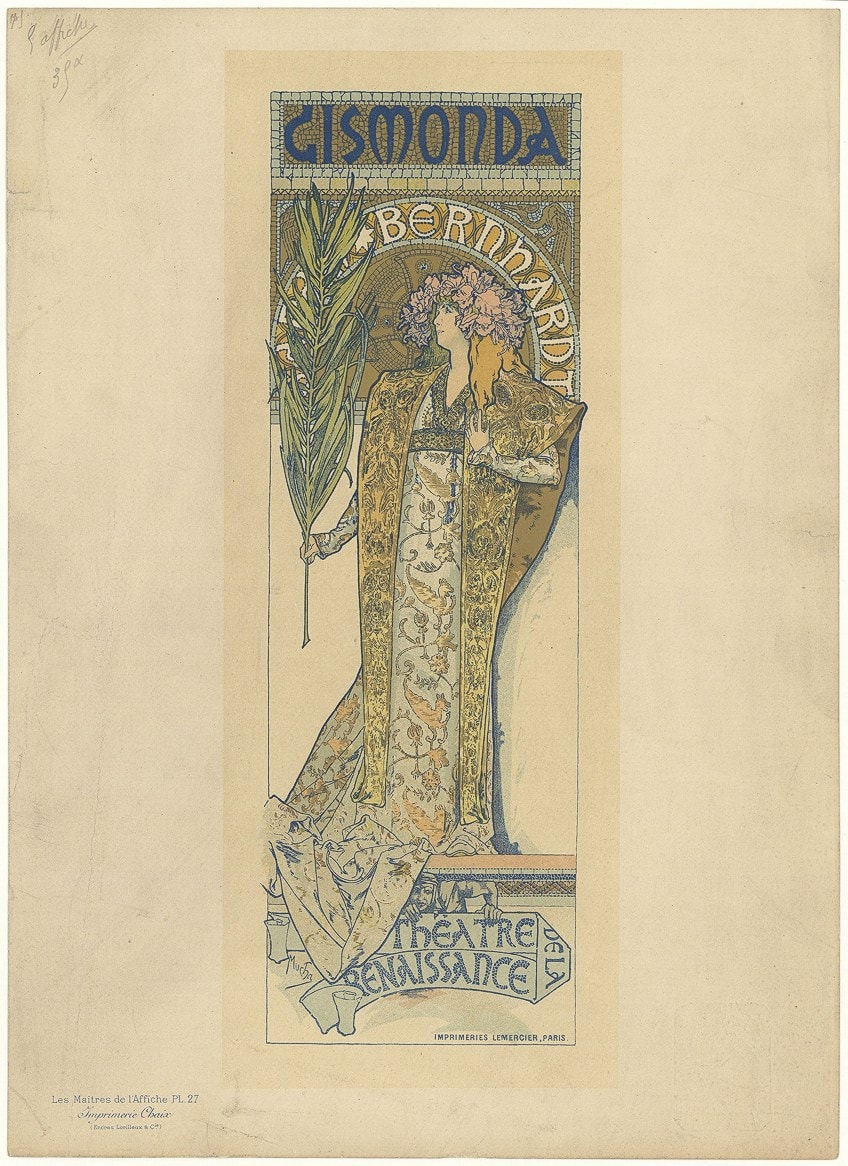

Gismonda (1894) by Alphonse Mucha

| Date Completed | 1894 |

| Medium | Lithograph Poster |

| Dimensions | 216 cm x 74 cm |

| Currently Located | Multiple Prints Exist |

Gismonda’s design is intricate and extensive, which is unexpected for someone attempting a fresh creative approach. Alphonse Mucha may have been intending to make a big impression with this image, which may lead to other customers seeking similar projects. Many of the essential components found in Mucha’s promotional posters can be found here, including elegantly designed typography to promote the event, ornamental details on the Art Nouveau woman, and ornately decorative accents across the rest of the backdrop.

Sarah Bernhardt, a prominent actress who would play a pivotal part in his career, was highlighted here.

A new show was about to premiere in Paris for the first time in early 1895, and the business behind it decided to hire Mucha to market it with a series of posters. We were still several years away from the internet or even the usage of television in the late 19th century, so print media was highly crucial in advertising everything and anything. There were a lot of prospective employment opportunities for any artist who could put their cause forward, and Mucha was one of the first.

Bernhardt, by the way, was not only an actor in the drama but also its director, so she may have had some say in who was chosen for the Art Nouveau artwork’s commission.

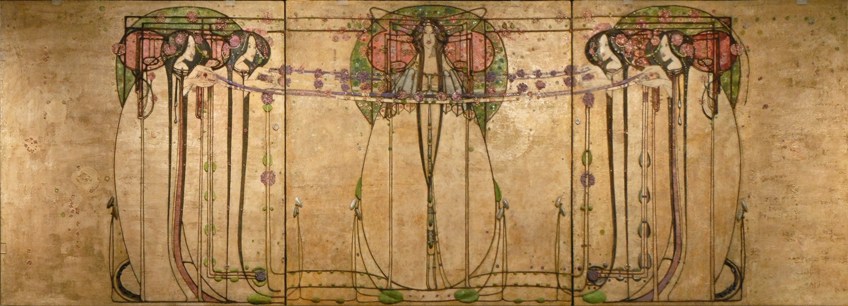

The May Queen (1900) by Margaret Macdonald

| Date Completed | 1900 |

| Medium | Oil Paint |

| Dimensions | 158 cm x 457 cm |

| Currently Located | Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum |

The May Queen is a famous piece by Margaret Macdonald, who made it in 1900, the very year she wedded fellow artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh. This piece was constructed particularly for Miss Cranston’s Ladies’ Luncheon Room. Charles, Margaret’s spouse, had been requested to design this area, and the pair collaborated to produce two exquisite sculptures that faced each other on different ends of the space, Charles’ The Wassail and Margaret’s The May Queen. They were the first of many interior designing assignments that they collaborated on as a partnership.

Due to the manner in which they were built, they were thought to be mostly exploratory pieces, and based on their size, they had to be treated with care on the voyage to and from Vienna.

The May Queen is an oil-painted gesso on cloth and gauze fabric with linear motifs produced using bits of string affixed to the painting, as well as seashells, beads, tin, and colored plaster “gems.” It fit the feminine style of the space so precisely, with female characters donning elaborate gowns and blossoms in lavenders, pastels, and emeralds, that it’s unclear if the artwork was made for the space or the setting for the artwork. The inside of the space had wide windows to let in natural light, which complemented the silver and white walls, as well as darker big tables and high-backed seats.

The lengthening of the furnishings was intended to accentuate the vast horizontal expanse, which was also represented in Margaret’s works by the graceful female protagonists, who were strikingly towering and straight.

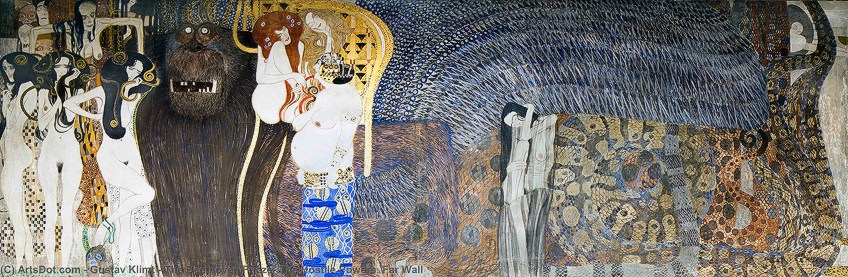

Beethoven Frieze (1902) by Gustav Klimt

| Date Completed | 1902 |

| Medium | Gold, Graphite, Casein paint |

| Dimensions | 2,15 m x 34 m |

| Currently Located | Secession Building, Vienna, Austria. |

The frieze depicts human longing for pleasure in a sad and turbulent world where one must struggle not just with outward evil powers but also with personal shortcomings. This voyage of knowledge is followed by the audience in a magnificent visual and linear form. It begins sweetly, with the hovering feminine Genii exploring the Planet, but quickly follows the gloomy, mysterious storm-wind monster Typhoeus.

In the first part of this horrific image, a gorilla symbolizes Typhoeus, the personification of the disease that ravaged European towns in the 19th century, especially Vienna.

The three gorgons would resurface as glamorous, seductive sirens with gold flowing through their hair in Klimt’s other contentious piece, Jurisprudence. Above them, the mad, emaciated visage of death and venereal sickness, both of which are prominent in Viennese society, glare down.

Klimt explores the contradictory concepts of deformity in form and mortality in love, and the work’s nakedness, with vivid black body hair, infuriated the Viennese aristocracy. The notions of Passion, Lusciousness, and Perversity are embodied in feminine shape on the gorilla’s right.

With her flashy, bedazzled attire, the huge, drooping form of Overindulgence resembles a prostitute mistress; the bright blue dress is the only ringing hue in the whole mural. As a result of his desire and affection for the desperate, struggling mankind, the hero clothed in dazzling armor comes. The voyage culminates in the revelation of pleasure via the arts, and fulfillment is symbolized by the tight touch of a kiss.

As a result, the mural expresses emotional human desire, which is finally gratified via personal and collective seeking, the majesty of the arts, and friendship and camaraderie.

The Kiss (1908) by Gustav Klimt

| Date Completed | 1908 |

| Medium | Gold Leaf and Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 180 cm x 180 cm |

| Currently Located | Österreichische Galerie Belvedere |

Gustav Klimt shows the pair in a loving hug upon a gold, flat backdrop. The two individuals are standing on the border of a flowery field that terminates under the female’s naked toes. The male is dressed in a cloak with intricate shapes and delicate spirals. He sports a vine headpiece, while the female adorns a floral headdress. She is dressed in a billowing gown with flower designs.

The spectator does not see the man’s face because he has stooped forward to kiss the female’s cheek, and his fingers are caressing the lady’s head. Her eyes are shut, one arm over the man’s shoulder, the other softly rested on his hand, and her head is tilted up to welcome the young man’s lips.

The motifs in the artwork allude to the Art Nouveau styles as well as the natural shapes of the Arts and Crafts school.

Simultaneously, the backdrop suggests the inherent struggle between two and three-dimensionality in Degas’ and other modernists’ artwork. Works like The Kiss are aesthetic expressions of the fin-de-siecle mentality because they depict the extravagance represented by sumptuous and sensual motifs. The employment of gold leaf harkens back to medieval gold-ground pictures, medieval manuscripts, and older murals, while the spiraling designs on the garments harken back to Bronze Age art and the ornamental spirals present in Western art from before ancient antiquity.

The man’s head terminates extremely close to the top of the painting, a deviation from typical Western norms that indicates Japanese print influences, as does the artwork’s streamlined arrangement.

The Slavs in Their Homeland (1928) by Alphonse Mucha

| Date Completed | 1912 |

| Medium | Tempera on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 610 cm x 610 cm |

| Currently Located | National Gallery, Prague |

Alphonse Mucha opted to begin his Slavic history exploration in the fourth to the sixth century. At that time, the Slavic clans were agrarian people who lived in the wetlands between the Vistula and Dnieper rivers, as well as the Black and Baltic seas.

Their communities were constantly attacked by Germanic peoples from the Countryside, who would destroy their dwellings and plunder their animals since they lacked a political framework to assist them.

The victims of one of these raids are the pair sheltering in the shrubs in the forefront as their hamlet burns in the distance. The terror and fragility in their expressions beg the public’s assistance. In the upper right corner of the painting, a pagan deity is accompanied by two youngsters representing battle and harmony.

These numbers foreshadow the Slavic people’s future liberty and tranquility if freedom is attained via a conflict.

Les Femmes Fatales (1933) by Gerda Wegener

| Date Completed | 1933 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 110 cm x 119 cm |

| Currently Located | Private Collection |

Les Femmes Fatale was created by Gerda Wegener, a Danish designer, and artist best known for her depictions of elegant ladies and femme Fatales in art nouveau styles. Her first spouse, Einar Wegener, recognized himself as feminine and became her favorite subject under the name Lili Elbe, before dying from sexual reassignment operations. Gerda’s artistic profession started after she graduated from the Academy in 1908 when she entered an art competition sponsored by the Politiken tabloid.

She was influenced by design and worked as an artist for magazines like “La Vie Parisienne” and others.

Wegener rose to prominence as a painter in France but had less luck in Denmark, where her works were deemed provocative. She was awarded a prize in the 1925 World’s Fair in Paris. She was well-known for her advertising graphics and was also a sought-after creator of Art Nouveau portraits. This beautiful piece embodies French Art Nouveau and depicts three fashionable women enjoying a relaxing repose in a stunning natural environment surrounded by butterflies and lush flora.

Art Nouveau artworks started in the 1880s with the purpose of updating style and rejecting formerly established traditional and historical forms. Natural features, such as wildflowers or beetles, inspired Art Nouveau painters. Curves, asymmetrical shapes, and bright colors were other popular features in the movement. The Art Nouveau styles were also seen in ornamental art, artworks, construction, and even commercials.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Art Nouveau Characteristics?

The traits of Art Nouveau are difficult to pinpoint, although the following are distinguishing features. The Art Nouveau movement pushed for the adaptation of aesthetic motifs to everyday items in order to make beautiful things more accessible to everyone. Nothing was too insignificant to be “beautified.” Art Nouveau, in essence, saw no distinction between fine art (paintings and sculptures) and utilitarian or fine art. The style was a reaction to an art world dominated by the rigorous symmetry of Neoclassical designs.

What Is Art Nouveau?

Art Nouveau is often seen as a “style” rather than a doctrine; yet, it was motivated by distinct ideals rather than just fanciful goals. All of the most dependable Art Nouveau designers shared devotion to pushing beyond the limits of neoclassicism – that exaggerated regard with historical concepts that characterize the majority of 19th-century styling: they desired a new visual style based on a raw assessment of the purpose and a close examination of the organic world.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Art Nouveau Paintings – A Look at the Art Nouveau Style of Art.” Art in Context. November 5, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/art-nouveau-paintings/

Meyer, I. (2021, 5 November). Art Nouveau Paintings – A Look at the Art Nouveau Style of Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/art-nouveau-paintings/

Meyer, Isabella. “Art Nouveau Paintings – A Look at the Art Nouveau Style of Art.” Art in Context, November 5, 2021. https://artincontext.org/art-nouveau-paintings/.