Charles Rennie Mackintosh – The Art of Charles Rennie Mackintosh

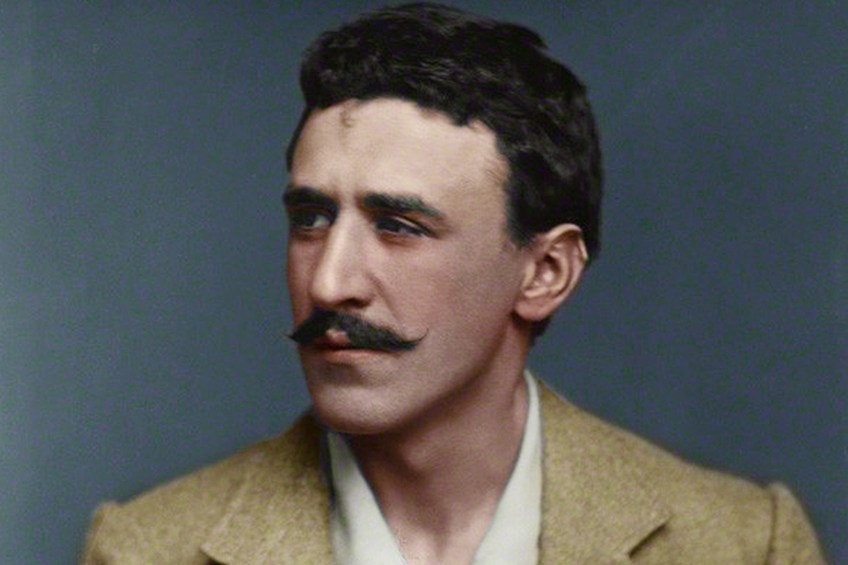

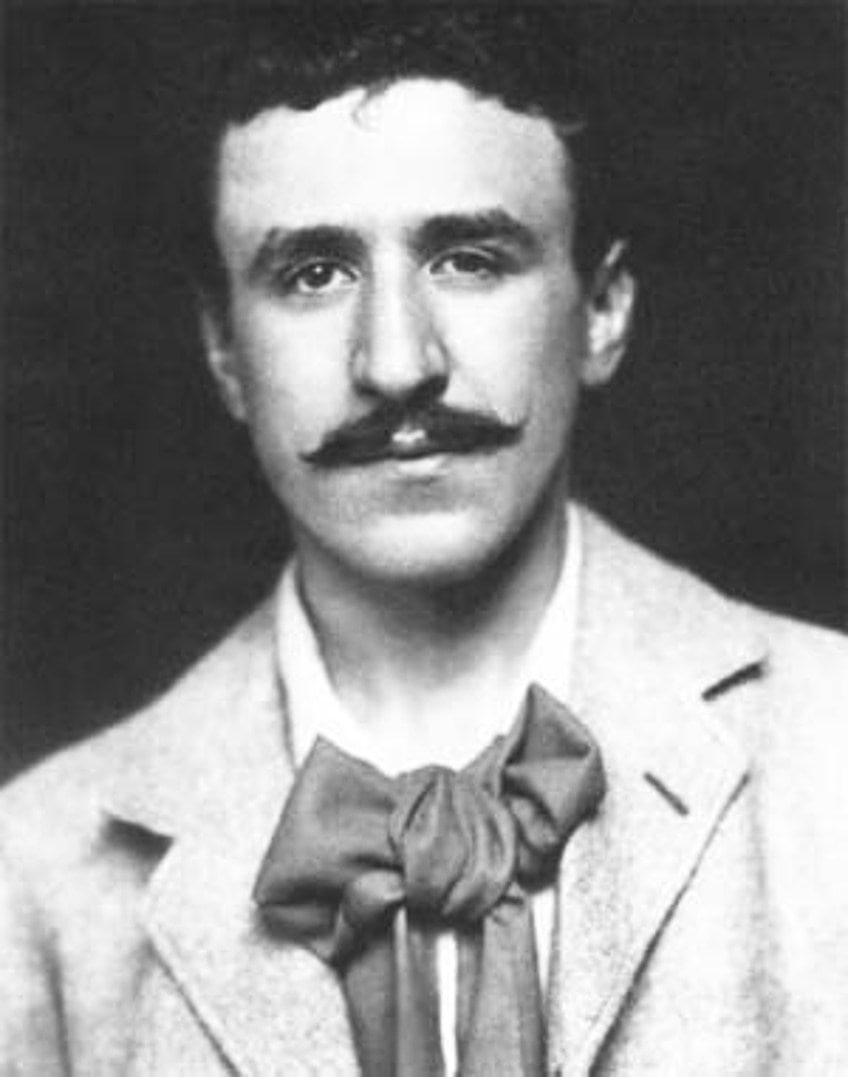

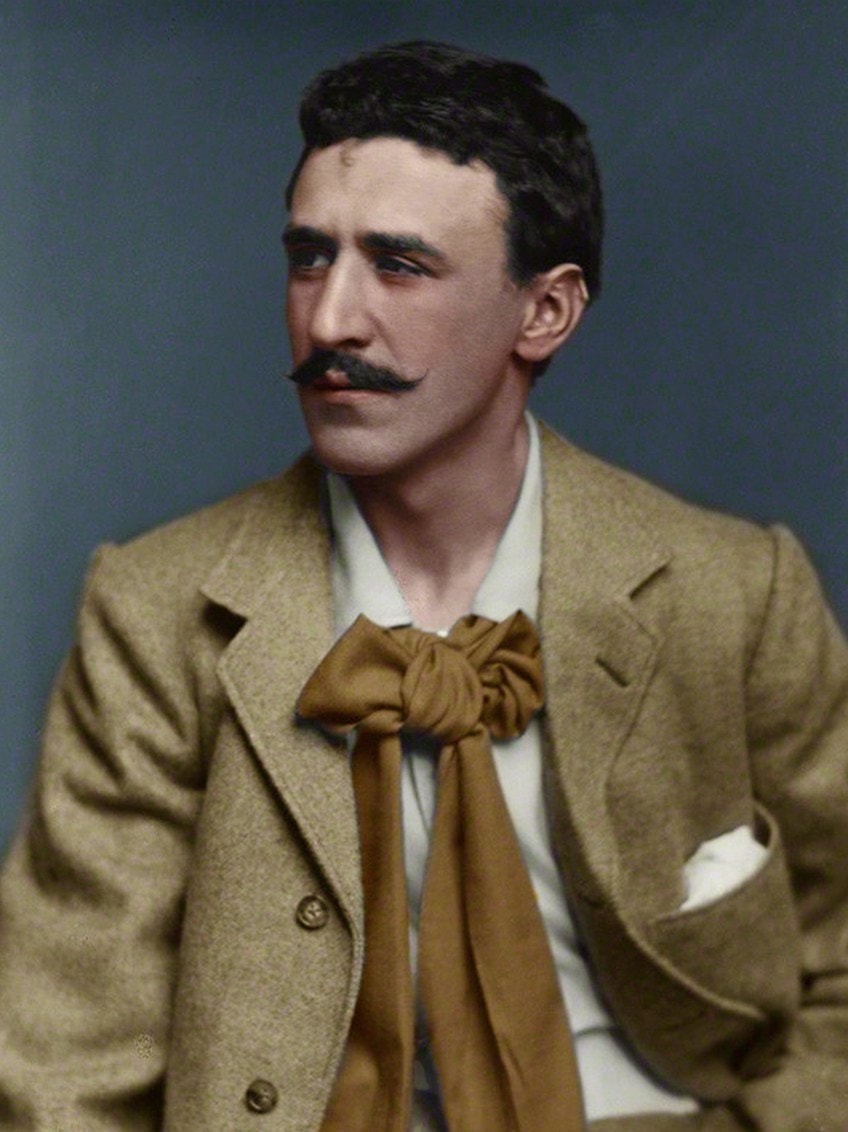

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was a respected architect known for creating buildings that exuded a serene atmosphere and seemed to breathe with life. He was not only an architect, though – Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s artwork also encompassed watercolors and interior designs. Among the most popular of his designs is the Charles Mackintosh rose, a perfect illustration of his distinctive use of soft curves and hard angles. To discover all the fascinating details about Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s biography and art, take a look at this in-depth article below.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Biography

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Date of Birth | 7 June 1868 |

| Date of Death | 10 December 1928 |

| Place of Birth | Glasgow, Scotland |

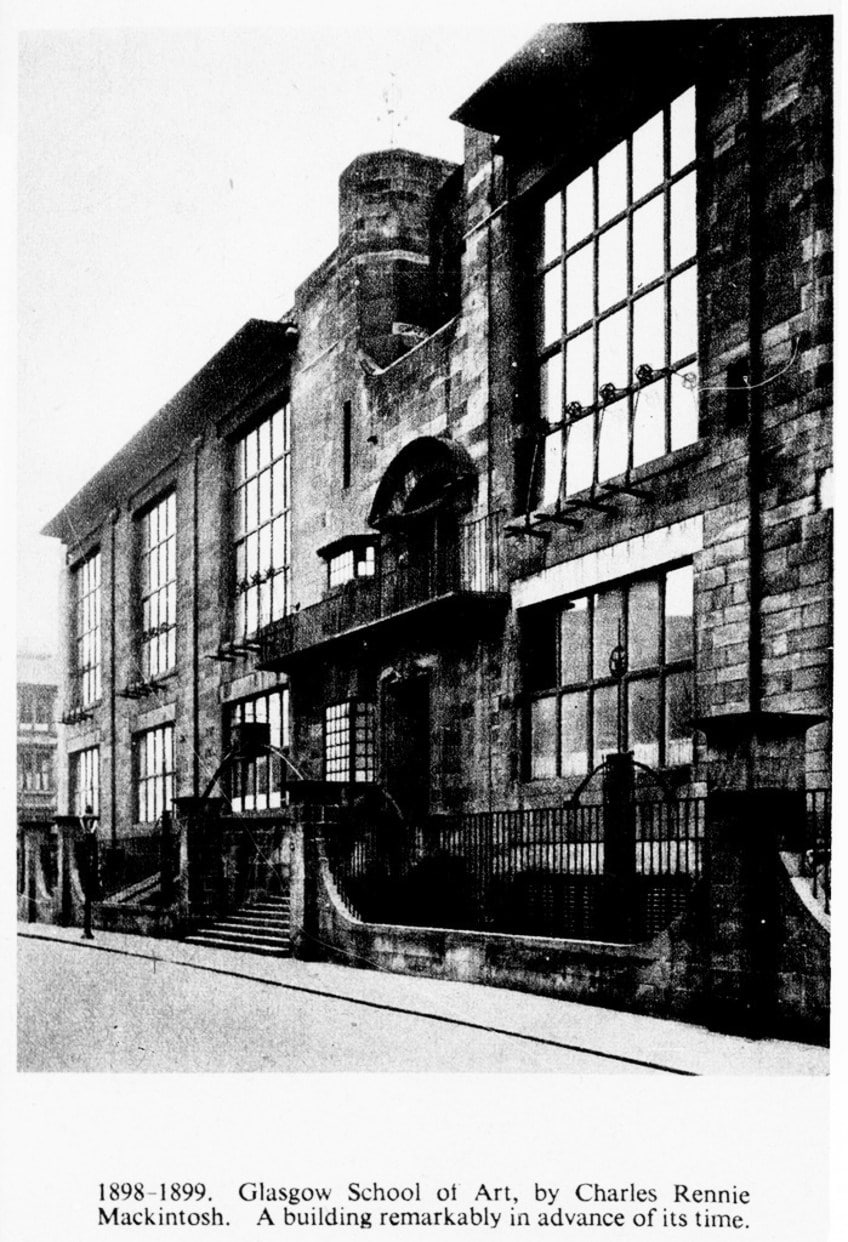

Despite the huge size and industrial materials of Mackintosh’s buildings, he was still able to create a sense of soft intimacy. Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s style of architecture was a fusion of his predominantly Symbolist style blended with Japonism’s Minimalistic restraint. After redesigning Glasgow’s School of Art, Charles Rennie Mackintosh helped turn Scotland into a globally recognized hub for creative design and art.

Childhood

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was one of 11 children (of which only seven survived past birth) but despite the huge number of children in the family, the house was always full of affection. His mother was often bedridden for months at a time due to ailing health or recovering from one of a continuous succession of childbirths. His father was a policeman, and also an avid vegetable gardener, which sparked his initial interest in botanical forms and organic growth.

As a young boy, Mackintosh was often prone to mood swings and emotional outbursts, and sketching was his way of escaping from the pressures of life and finding some peace within himself.

During this time, after suffering a nasty bout of rheumatic fever, one side of his face was left with a permanent droop. After moving to a larger home, Mackintosh was given the basement as his room and, inspired by the space, he began to decorate and renovate it, leading to a lifelong love for interior design.

Education and Training

As a teenager, he attended Allen Glen High, and even at that age displayed a great ability to produce technical drawings and architectural designs. He enrolled at Glasgow’s School of Art for part-time courses at the age of 15, serving as an apprentice to John Hutchinson, and collaborating in commissions for the next 10 years. Despite receiving much support from his relatives, they were concerned that he was overworking himself. While at the School of Art, he also trained to be a painter under Francis Newberry, the institution’s director.

At the age of 17, Mackintosh’s mother passed away, and he decided to explore Europe, specifically Italy, where his sketchbooks were filled with drawings of the Gothic, Byzantine, and Romanesque buildings he encountered there.

He returned to Glasgow in 1889 and was offered a position at Honeymoon and Keppie, a respected architectural company.

While there, not only did his personal philosophies and aesthetics begin to emerge, but also his increasing aversion to compromise in groups. His position at the company was further strained when his engagement with Kelpie’s sister was broken off due to his mood swings and erratic behavior. He would meet his next wife, Margaret Macdonald in 1892, a respected artist in her own right.

Mature Period

The commission for the redesign of Glasgow’s School of Art was won by Honeymoon and Keppie in 1897, however, despite Mackintosh having done most of the work for the project, Keppie was the one publicly introduced as the architect at the opening ceremony in 1899. This frustrated Mackintosh immensely and he confided in a friend that he hoped to one day have his own firm and be able to gain the proper acknowledgment for his architectural achievements. Even though his furniture designs did not resonate with people in Glasgow, he started to receive the praise he sought when his designs started to make waves in Belgium after they were sent to artists there by Francis Newberry.

This was a turning point for Charles Rennie Mackintosh, as thereafter his designs started being admired across Europe for their innovative concepts. This eventually led to the architect being invited to create designs for the 8th Vienna Secessionist Exhibition in 1900. That same year, he married Macdonald and they moved into an apartment that became a regular stop-off point for artists passing through from all around Europe. The couple experienced a fruitful and creative few years creating art during this period, often looking after their friends’ children, as they had none of their own.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh also started to receive many large private commissions during this period, such as architectural and interior design work for Hill House, and several tea rooms for Catherine Cranston, the renowned businesswoman.

With both of these projects, the clients gave him total creative freedom to do as he wished, resulting in incredibly beautiful designs such as the Willow Tearooms. These spaces were intended by Cranston to be a haven where people could enjoy tea while appreciating and discussing art.

There were different sections for women and men and each of these was uniquely decorated and painted.

In 1904, the couple then moved to a bigger home after Mackintosh was offered a position as a partner at the company. During the eight years that they resided there, they once again experienced a period of inspired creative flow in their works.

However, due to the out-of-town location of their new home, Mackintosh found it harder to get commissions for new designs.

This changed when his designs for the second part of the School of Art were approved in 1907 and eventually completed two years later. Once again, Keppie was lauded as the main designer, which pushed Mackintosh into a dark period of depression and drinking, compounded by the death of his father. This led to him retreating both socially and from work, and the company eventually asked him to resign as a partner.

Late Period

They once again moved in 1914, this time to Walberswick, an artist community in Suffolk. There they enjoyed the first few years creating collaborative watercolor artworks with botanical themes. However, due to his eccentric ways, he was suspected of being a German spy, and although eventually let go without any charges filed against him, he found himself shunned by the locals and departed for London shortly after.

Once in London, securing commissions proved difficult and he began to grow increasingly reclusive due to his declining mental health and financial strains. Meanwhile, his wife grew increasingly more social, hanging out with the bohemian art crowd in the city at night.

They eventually grew tired of the dreary London weather and relocated to a little town along the coast in France called Port Vendres. In this sunny environment, Mackintosh found himself feeling re-energized and experienced a period of creative release, producing beautiful landscape paintings of the local surroundings.

Unfortunately, their time there would be short-lived, as they both had to return to London to attend to various ailments they were suffering from, as the city provided the necessary medical expertise required. This included regular visits to the hospital for Mackintosh who had developed a growth on his tongue. While receiving treatment at the facility, he passed his time sketching and showing other patients how to draw until he was found dead in 1928, still clutching a pencil in one hand.

Legacy

While his other Modernist colleagues were trying to create “machines for living”, Charles Rennie Mackintosh sought to create intimate and peaceful environments that were strongly influenced by Japanese design principles. This Minimalist aesthetic was ahead of its time and currently experiencing a resurgence of interest in the interior designs of 21st-century houses. However, at the time that his works were created, there were not regarded as fashionable enough and were dismissed as barely worthy of any further critique.

His work experienced a resurgence of interest in the 1960s though, as Art Nouveau once again became a trendy style and was experiencing a revival.

By the following decade, most of the tea rooms he had gained fame for were fast disappearing, as were the public’s memories of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. But luckily the Mackintosh Society was formed in 1973 to promote the conservation of his remaining buildings and to educate the masses as to what his achievements had been. Unlike many of his fellow architects, he did not wish to create architectural masterworks that jutted out of the landscape surrounding it, but rather designed artist homes that gently merged into their environment, in a soft, unobtrusive manner.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Artworks and Designs

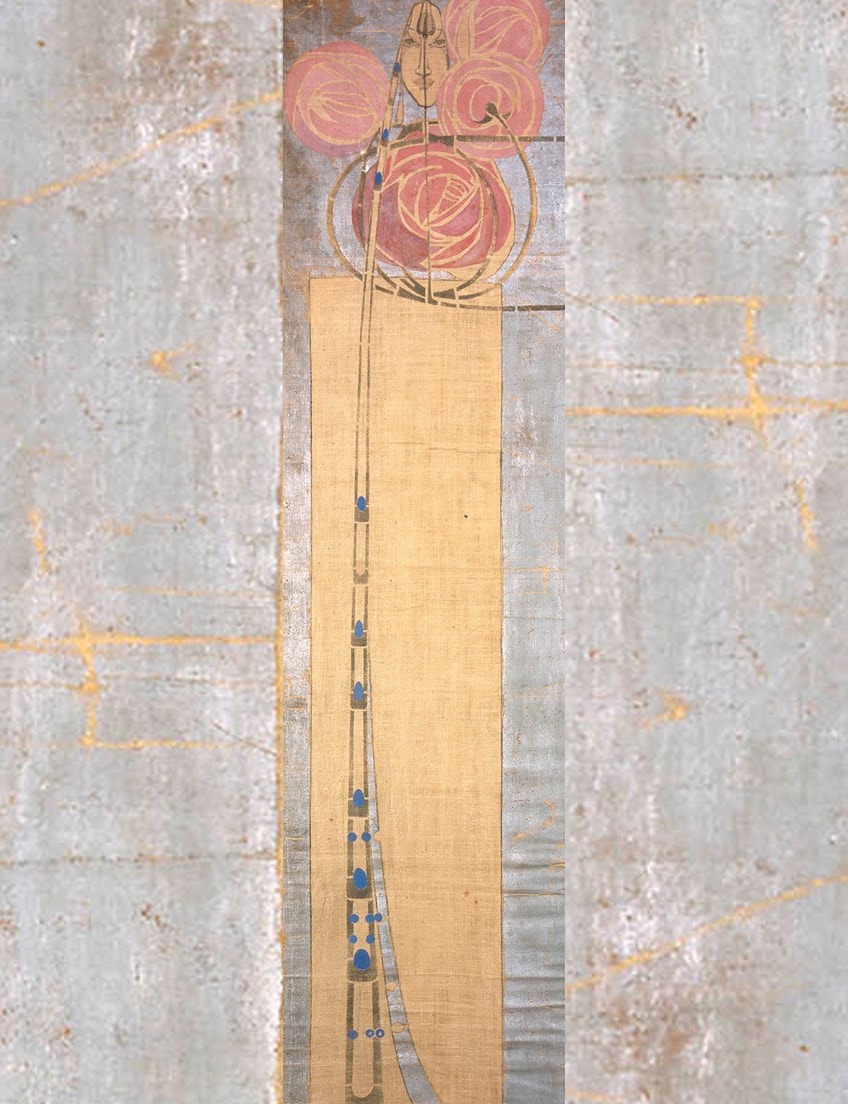

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s rose design was among the many floral motifs he created, proving that he was as much as home creating watercolor artworks as he was innovative architectural designs or interiors. For him, painting flowers was in essence trying to capture the work of the ultimate designer – nature.

Here are some notable examples of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s artwork and designs.

Interior for Mackintosh’s Main Street Flat (1900)

| Date Completed | 1900 |

| Function | Home |

| Medium | Glass, wood |

| Location | Glasgow, Scotland |

Just before his marriage to Margaret Macdonald, Mackintosh started designing the interior space of their new home in Glasgow. Everything was so meticulously placed in the largely minimalist area that every object seemed to add to the overall harmony of the room. Extra touches were added to the space such as a gently curving wooden piece for the top of the fireplace, making the space feel soft and homey. The minimalist aesthetic was enhanced by the lack of clutter, gentle coloring, and clean lines throughout.

This was very different from the typical, rather stuffy, and dark interiors of the drapery-laden Victorian interior spaces that were prominent at that time.

While much of the original flat remained as it was found, the couple did bring in certain extra pieces such as modified furniture from their previous residence, a desk, and a smoker’s cabinet. Macdonald also added decorative panels that were custom designed to fit into their new home.

The rooms were decorated in understated and subtle color combinations such as white and gray, or the dining room’s black, white, and brown palette.

Each room was decorated with Japanese prints which adorned the otherwise bare walls. As we only have the black and white photos to hint at what the residence really looked like, in reality, there was much more color used in the space than it appears. For instance, in their bedroom, the stained glass is actually purple in color, and the panels were painted green.

Room de Luxe in the Willow Tearooms (1903)

| Date Completed | 1903 |

| Function | Tearoom |

| Medium | Textiles, glass, wood |

| Location | Glasgow, Scotland |

During the early 1900s, Glasgow was full of clubs designed for working men who enjoyed unwinding after work with a couple of drinks. There was also a movement that arose at that time known as the Temperance movement, who were opposed to the use of alcohol and instead, communed in specially designed tearooms where they could socialize and discuss art instead of being exposed to the more unrefined elements of Scottish society. These tearooms were all designed by Mackintosh, who had been given total creative control of the project by their owner Catherine Cranston.

Richly colored timber ceilings were once a feature of the Willow Tearoom, which was another design element borrowed from Japanese interior design.

When the tearooms first opened, guests would enter through the completely white facade of the building and then walk between various decorated metal screens to enter the space filled with tall back chairs. Images of fruit, women, peacocks, and roses adorned wall panels lining the rooms.

These images were all meant to represent symbolic references used by the avant-garde Symbolist movement.

These were often interpreted as having sexual undertones and meanings by guests, which was indicative of the difference in interpretation between those from within the movement, and those looking in. However, this might have been an intentional choice, meant to act as a controversial conversation piece intended to draw potential clients into the tearooms.

Hill House (1904)

| Date Completed | 1904 |

| Function | Residence |

| Medium | Iron, glass, stone, wood |

| Location | Helensburgh, Scotland |

Hill House is yet another example of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s diverse influences and taste in styles. One can notice a strong influence from the Arts and Crafts style, the Baronial style, and the designs of CFA Voysey. The front door is located in a deeply recessed portico between very thick walls. The interior was actually designed first, and the external structure around that design.

This reflected his desire for his architecture to represent an integrated whole, where unifying the building into a single entity was more important than any single aspect on its own.

The library was made of dark timber and featured vibrantly colored glass. The stained glass features images of naked figures and flowers, their colorful reflections moving across the space as the light flooding from above the stairwell changes position throughout the day. The facade also featured elements that were created from hard and rough materials yet were shaped and presented in a way that made the overall appearance seem softer and more approachable.

This is the last building designed by Mackintosh to still survive, since his most well-known architectural work, Glasgow’s School of Art, was completely destroyed in a terrible fire.

Glasgow School of Art (1909)

| Date Completed | 1909 |

| Function | School |

| Medium | Iron, stone, glass, wood |

| Location | Glasgow, Scotland |

Mackintosh was responsible for the redesign of the School of Art’s interior and exterior, and his aim was to turn the facility into the flagship of his pluralist architecture style. He was inspired by the majestic Baronial towers of Scotland and considered their use of glass, iron, and stone to be very modern looking for their time.

His ideal appearance for his building designs was a mixture of traditional national styles and his unique personal free-flow aesthetic.

A prominent feature of the building’s interior design is the Japanese influence, visible in the effective yet restrained use of decorative elements throughout. There is also a hint of the Bauhaus influence with the incorporation of a rectilinear form and distinctive window design.

Mackintosh’s interior design philosophy expressed a desire to unify the spirit and body by creating interior spaces that were a perfect symbiosis of both form and function.

The library, which was located in the center of the building, was reminiscent of Japanese home designs, with the interior spaces illuminated by the sunlight entering through the massive windows and the area divided by wooden beams. The studio rooms were all rather minimal and austere in character, yet balanced by the decorative addition of Art Nouveau-style floral ironwork. These stylistic contrasts were a common feature in Mackintosh’s designs, reflecting his desire to blend the pure with the sensual.

Fritillaria (1915)

| Date Completed | 1915 |

| Function | Artwork |

| Medium | Watercolor |

| Location | Hunterian Museum, Glasgow |

Besides his well-known architectural and interior designs, Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s artwork also includes his watercolor flower studies. Around 30 various flower studies were produced by the artist when the couple was staying in Walberswick, the paintings were originally intended to be used in a book, but the untimely arrival of World War I put an end to those plans.

Mackintosh managed to create a highly stylized yet natural-looking painting that perfectly blended botanical accuracy with a fair amount of artistic license.

Several of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s artworks were produced in collaboration with his wife Margaret Macdonald. For the artists the various elements of the painting represented something unique: the leaves and stems of the plant were life, and the flowers that grew from them were art. And just as one offers flowers, one should offer their art to the world as a gift, a piece of themselves manifest in a creative expression and shared with the world around them. With both the intended symbols and the true-to-life aesthetic, this artwork represents the meeting point of his Symbolist tendencies with the more commercial landscape paintings of his French period.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was a renowned modernist architect who embraced the minimalistic aesthetic of Japanese designs. His work is known for its soft and curving design, clean lines, and uncluttered layouts. Together with his wife Margaret Macdonald, Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s artwork also included floral watercolors and motifs, such as Rennie Mackintosh’s roses. Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s biography reveals extreme ups and downs, which while may have added to his general mental deterioration, were also the source of his creative moments of sublime inspiration.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Charles Rennie Mackintosh?

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was an architect as well as an interior designer and artist. His designs were always clean and minimal yet homey at the same time, juxtaposing austere spaces with ornate embellishments, mixing the realms of the sexual and the puritan. Although very talented, he did not always receive the recognition that he had earned and that would often lead him to bouts of depression, alcoholism, and despair. Moving to sunnier regions helped renew his creativity, but unfortunately, he was forced to return to London in order to attend the hospital regularly as he had a cancerous growth forming in his mouth.

What Were Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Artworks About?

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was a talented and artistic individual who was a successful architect as well as a watercolorist. He not only painted alone but also created pieces in collaboration with his wife Margaret Macdonald, creating iconic motifs such as the Rennie Mackintosh rose. His desire as a designer was to create spaces that were minimal yet had touches that added a subtle feeling of comfort and harmony. His architectural works were viewed as unified pieces, where neither the interior nor exterior took center stage, but rather worked together to create a space that was lively, warm, creative, and welcoming, without becoming cluttered or stuffy. In an era of dark and heavy atmospheres, thick curtains, and dim lighting, his clean aesthetic was viewed as a breath of fresh air to the public as well as other artists.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Charles Rennie Mackintosh – The Art of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.” Art in Context. August 30, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/charles-rennie-mackintosh/

Meyer, I. (2022, 30 August). Charles Rennie Mackintosh – The Art of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/charles-rennie-mackintosh/

Meyer, Isabella. “Charles Rennie Mackintosh – The Art of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.” Art in Context, August 30, 2022. https://artincontext.org/charles-rennie-mackintosh/.