Iconoclasm – Looking at the History of Icons in Iconoclasm Art

What is Iconoclasm? If you are searching for an Iconoclastic meaning or definition, then perhaps the following description might help: Iconoclasm is the intentional destruction of religious icons or structures for either political or religious reasons. Iconoclasts are those who participate in or advocate iconoclasm, a word that has come to be extended symbolically to anybody who defies or rejects established doctrine or traditions.

What Is Iconoclasm?

In the Christian history of icons, there were two distinct periods in the 8th and 9th centuries which centered on the destruction of Byzantine icons. Subsequently, during the Protestant Reformation, significant occurrences of Christian iconoclasm occurred. Iconoclasm was also visible throughout the liberal uprisings of the French Revolution, as well as throughout Russia and China’s Communist rebellions.

Iconoclasts are people who criticize deeply held ideas or established institutions as founded on ignorance or superstitions.

Biblical Iconoclasm

The most notable iconoclastic occurrence in the Scripture is the Golden Calf occurrence, in which Moses led the demolition of the idol that the Israelites had built when Moses had been on Mount Sinai (Exodus 32). The following scriptural passages authorize such behavior:

- Leviticus 26:1: “Do not construct deities or set up a figure or a holy monument for yourselves, and do not establish a carved monument in your territory to bend down before it”, the Bible says.

- Numbers 33:52: “Force out all previous occupants of the property. Eliminate all of their sculpted pictures and cast deities, as well as all of their high positions”.

- Deuteronomy 7:25: “You are to destroy the pictures of their deities in the fire. Do not desire the silver or gold on them, and never grab it for yourself, or one will be trapped by it since it is abhorrent to the Lord your God”.

There were two sorts of iconoclasm in the Bible: the demolition of pagan deity altars and sculptures, and the demolition of Israelite pillars, sculptures, and other icons praising Yahweh. Because the Temple of Jerusalem was regarded as the sole approved location of sacrifice, ancient authors lauded Judean monarchs for removing Canaanite idols and deconstructing Israelite shrines at the high places.

In the kingdom of Israel to the north, king Jehu received praise for demolishing the sanctuary and shrine of Baal in Samaria’s main city, but he permitted the golden calves erected to Yahweh, for which the authors of the Books of Kings chastised him.

The largest iconoclast in religious scholarship was King Josiah of Judah, who eventually razed the altar at Bethel, something that even Jehu had preserved, and also launched a crusade to remove all heathen and Yahwist sanctuaries in his dominion save the Temple of Jerusalem.

Josiah would be regarded as the strongest ruler since David because of his iconoclastic fervor.

Christian Traditions of the Early Period

Because the first Christians were indeed Jews, the earliest church’s practice did not include the usage of religious icons. Moreover, many Christians would rather have died than make offerings to the idols of Roman deities, and even eating a meal offered in pagan sanctuaries was forbidden for early Christians. Acts 19 narrates the tale of how the idol builders of Ephesus were concerned that the Apostle Paul’s teachings might harm their business in Artemis figures trading.

Yet, as Christianity moved away from its Jewish origins, it soon started to include “pagan” customs such as the veneration of icons of Mary and Jesus, while still detesting depictions of pagan gods.

Christian iconography was abundant by the third century C.E. Pagan shrines, sculptures, and other symbols were not protected from Christian attacks once Christianity became the state’s preferred religion in the fourth century. Many of the mutilated or decapitated sculptures of Greco-Roman art that are still in existence today are the result of Christian iconoclasm.

The Temple of Artemis in Ephesus was one of many ancient and Jewish structures that would be demolished by Christian persecution, both state and mob-related. As Christianity expanded throughout pagan Europe, preachers such as Saint Boniface considered themselves modern-day messengers sent by God to fight paganism by demolishing native monuments and sacred woods.

Likewise, Christian iconography grew into a prominent art style.

Muslim Iconoclasm

In opposition to Christianity, Islam has a stringent prohibition prohibiting visual depictions of God, biblical characters, and saints. In 630, one of the prophets Muhammad’s most renowned deeds was the destruction of pagan Arabic idols located in the Kaaba in Mecca.

Nonetheless, Muslim reverence for Jews and Christians as “folks of the Book” led to the safeguarding of places of Christian worship, and therefore there was some tolerance for Christian iconography.

Even though conquering Muslim forces occasionally defiled Christian monuments, most Christians living under Muslim authority continued to manufacture icons and adorn their buildings as they saw fit. The Edict of Yazd, which had been sent out by the Umayyad Caliph Yazid II in around the year 723, was a notable deviation from this tendency of moderation. This directive mandated the demolition of crosses and Christian icons inside the caliphate’s realm.

However, Yazd’s iconoclastic methods were not followed by his successors, and the creation of symbols by the Christian populations of the Levant proceeded uninterrupted from the sixth to the ninth centuries.

Byzantine Icons and Iconoclasm

The Byzantine Christian iconoclastic period arose from the establishment of earlier Islamic iconoclasm, to which this is partially a response. It sparked one of the most heated theological debates in Christian history. As with other theological concerns during the Byzantine Empire, the debate over iconoclasm was not limited to the priesthood or theological debates.

The ongoing cultural conflict with Islam, as well as the physical threat posed by the rising Muslim empire, caused significant hostility to the usage of icons among some segments of the populace and Christian bishops, particularly in the Eastern Roman Empire.

Some of these people believed that symbols were insulting to God and/or that they backed Muslims’ and Jews’ claims that their religions were more closely aligned with God’s will than Christianity was. Some immigrants from Muslim-controlled areas appear to have imported iconoclastic notions into public piety of the day, most particularly among soldiers.

Emperor Justinian II introduced a depiction of Jesus on his gold coins in 695. This “graven picture” appears to have persuaded Muslim Caliph Abd al-Malik to abandon his prior usage of Byzantine coin types, adopting a fully Islamic currency with text alone.

At the beginning of the eighth century, Patriarch Germanus I of Constantinople stated that “today large villages and masses of people are in tremendous excitement about this topic.” These sentiments would soon spread to the imperial court.

730 – 787: The First Period

Between 726 and 730, Byzantine Emperor Leo III Isaurian commanded the dismantling of a figure of Jesus conspicuously displayed over Constantinople’s royal entrance. According to sources, one of the reasons for the removal was Leo’s military defeats against Muslim armies, as well as the explosion of the volcanic island of Thera, which Leo came to consider as confirmation of Divine punishment in response to Christian idolatry. Some of those tasked with removing the icon were assassinated by an anti-removal organization known as the iconodules (lovers of icons).

Undaunted, Leo issued an edict in 730 prohibiting the worship of holy icons. His agents seized a large amount of church property, along with not just venerated icons and statues, but also costly plates, candelabra, altar linens, and reliquaries ornamented with holy images.

The order did not extend to non-religious artwork, such as the emperor’s visage on coins, or to religious icons that did not depict holy beings, such as the Cross without the figure of Christ on it.

Patriarch Germanus I was opposed to the prohibition because it conceded to the faulty theological claims of Muslims and Jews over the usage of holy pictures. According to various sources, his subsequent departure from office was the result of being ousted by Leo or quitting in protest. In the West, Pope Gregory III convened two synods in Rome that denounced Leo’s acts, resulting in yet another rift between Rome and Constantinople. Leo responded by taking some estates within the jurisdiction of the Pope.

In 740, when Leo died, his prohibition on icons was upheld by his son Constantine V during his rule. The new emperor also had little trouble recruiting churchmen who backed this approach at the Iconoclast Council, in which 338 bishops attended and explicitly denounced the adoration of icons. The following curses were pronounced during this council: “If someone dares to use material hues to symbolize the holy form of the Word after the Incarnation, let him be accursed!” and “If somebody tries to reproduce the shapes of the saints in inanimate images with worthless material colors (because this thought is foolish and given by the devil), allow him to be accursed!”

During this time, complicated religious debates for and against the usage of icons emerged. Monasteries were frequently strongholds of icon devotion. Monks formed an underground system of anti-iconoclasts.

Through his doctrinal studies, John of Damascus became a key critic of iconoclasm. Theodore the Studite was another important iconodule. In response to monastic resistance to his policies, Constantine V acted against the institutions, had artifacts dumped into the sea, and even prohibited the spoken invoking of saints. His son, Leo IV, was less strict in his iconoclastic stance and tried to appease the factions. Nevertheless, at the end of his life, he took strong steps against pictures and was rumored to be prepared to imprison his secret iconodule spouse, Empress Irene, if not for his death.

The very first iconoclastic phase would come to a close with Irene’s election as regent. She convened a new ecumenical assembly, eventually known as the Second Council of Nicaea, at Constantinople in 786, but it was disturbed by pro-iconoclast armed troops.

It met again at Nicea in 787 to overturn the rulings of the preceding Iconoclast Council held in Constantinople and Hieria, renaming itself the Seventh Ecumenical Council. Unlike the Iconoclast Council, the pope endorsed the decrees of this council. However, Pope Leo III refused to acknowledge Irene’s administration and rather utilized her rule to appoint Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor.

814 – 842: The Second Iconoclastic Period

In 813, Emperor Leo V started the second phase of iconoclasm, presumably influenced in part by military defeats that he perceived as evidence of divine wrath, as his predecessor Leo the Isaurian had been. Michael II, who succeeded Leo, ratified the ordinances of the Iconoclast Council of 754. In his 824 letters to Louis the Pious, Michael II bemoans the legacy of image devotion, as well as customs like using icons as baptismal godfathers for children.

Michael’s son, Theophilus, followed him, and when he died, he named his wife Theodora guardian for his young heir, Michael III. In 843, Theodora, like Irene 50 years before her, obtained the assistance of iconodule monks and priests and declared the resurrection of icons.

Since that period, the first Sunday of Lent has been observed as the festival of the “Triumph of Orthodoxy” in Orthodox churches.

Islamic Iconoclasm

Muslim forces have occasionally destroyed pagan and Christian icons, as well as other works of art. Despite a theological restriction against the destruction of Christian and Jewish buildings of worship, shrines or places of worship were turned into mosques. One noteworthy example is Istanbul’s (previously Constantinople’s) Hagia Sophia, which was transformed into a mosque in 1453. The majority of its iconography was either defiled or plastered over. The Hagia Sophia was transformed into a museum in the 1920s, and the American Byzantine Institute began restoring its mosaics in 1932.

More spectacular examples of Muslim iconoclasm may be seen in regions of India, where Buddhist and Hindu temples were demolished and mosques were built in their place, such as the Qutub Complex.

Several Muslim denominations keep pursuing iconoclastic agendas targeted toward fellow Muslims in the modern and current eras. This is especially true in disputes between stringent Sunni sects like Wahhabism and the Shiite tradition, which permits the representation and reverence of Muslim saints.

Mecca’s Wahhabist rulers have also destroyed ancient structures that they felt were or would become the focus of “idolatry.” Occasionally, some Muslim organizations have perpetrated acts of iconoclasm against devotional icons of other religions. The Taliban, a militant Muslim sect and nationalist party, destroyed paintings and gigantic Buddha sculptures at Bamiyan in 2001. In portions of North Africa, similar acts of iconoclasm happened.

Several historic Buddhist monasteries and Hindu shrines in India were seized and rebuilt into mosques. In recent times, right-wing Hindu nationalists have sought to demolish several of these mosques, including the iconic Babri Masjid, and substitute them with Hindu temples.

Reformation Iconoclasm

Before the Reformation, many proto-Protestant revolts against church riches and corruption included iconoclasm. Churches were occasionally defiled, and icons, crucifixes, and reliquaries were taken or destroyed, frequently for the precious gold, silver, and gems that framed them as much as for any religious reason. Some Protestant reformers, notably Huldrych Zwingli, and John Calvin, advocated for the destruction of religious icons by citing the Ten Commandments’ prohibition on idolatry and the creation of graven images.

As a result, sculptures and portraits have been vandalized in both impulsive specific attacks and unlawful iconoclastic mob movements.

Iconoclasm also became a major influence in Protestant England, particularly during the time following up to and during Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan administration. Bishop Joseph Hall of Norwich recorded the events of 1643 when soldiers and civilians invaded his church, prompted by a parliamentary law against “superstition and idol worship”.

The government hired and paid the fanatical Puritan William Dowsing to visit the townships of East Anglia, removing paintings in churches. His thorough account of his path of destruction across Suffolk and Cambridgeshire has been preserved.

He stated: “We dismantled nearly a hundred superstitious images, including seven friars caressing a nun, a depiction of God and Christ, and several other extremely superstitious images. And 200 had broken down before I arrived. We removed two inscriptions and smashed a large stone cross on the church’s roof. We dismantled nearly a hundred superstitious images, including seven friars caressing a nun, a depiction of God and Christ, and several other extremely superstitious images. And 200 had broken down before I arrived. We removed two inscriptions and smashed a large stone cross on the church’s roof.”

Secularist Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm was also present in secular movements like the French Revolution, as well as the Russian and Chinese Communist upheavals. During the French Revolution, anti-royalist and anti-Catholic crowds frequently poured their rage at Catholic shrines, damaging religious artwork as well as sculptures and paintings of rulers.

Throughout the Russian Revolution, Communist officials supported extensive destruction of religious symbols, which they saw as a critical method of preserving “bourgeois ideology” and prevented the masses from embracing the state’s socialist principles.

Churches became the subject of assaults against “western imperialism” throughout the Communist takeover of China, while Buddhist or other religious sites were demolished as vestiges of the old order. During the Cultural Revolution, Maoist crowds destroyed religious and secular images throughout China, both in Han and Tibetan areas.

Following China’s lead, North Korea outlawed crosses and symbols in private residences, as well as Buddhist or even other religious shrines, and replaced them with iconic images of Kim Il Sung. Pyongyang, dubbed the “Jerusalem of the East”, was bereft of churches until recently when the government erected a solitary official church, to which foreign visitors are frequently welcomed.

Philosophical Iconoclasts

In a larger sense, an iconoclast is someone who questions assumed “common knowledge” or old institutions as being founded on mistakes or superstition. In this context, Albert Einstein could also be considered an iconoclast for questioning Newtonian physics in the early 20th century. Martin Luther King, Jr. was an iconoclast for condemning separation in the southern United States in the 1950s and 1960s, even though neither of them taunted physical icons.

By the same logic, individuals who advocate for a reversion to segregation now may be labeled as iconoclasts, as racial unification has now become the dominant political agenda.

The word can be given to anybody who questions the dominant orthodoxy in any subject, and an iconoclast in one setting (for instance, a member of a conservative Christian congregation who openly supports the evolutionary theory) may not be an iconoclast in another.

Examples of Iconoclasm

There are many reasons throughout history that people have damaged art, structures, and statues. Sometimes these reasons might be motivated by religious or political reasons. Other times it may have occurred as an act of persecution or protest. Here is a list of a few examples of Iconoclasm.

Cathedral of Saint Martin Reliefs (Utrecht – Netherlands)

An example of religious Iconoclasm wherein relief statues were heavily damaged by Calvinists who cut off the head of every figure in the relief. The effect of the sort of iconoclastic violence shown is plainly visible in this broken relief figure.

The destroyed faces of Mary and the other characters have a powerful force now, as they attest to the loss or destruction of a rich and vibrant cultural history.

The Toppling of the Statue of Lenin

Regarded as Riotous or Political Iconoclasm, this work of art represented oppression for many of the people who had to view it daily under his rule. Some Lenin monuments are discreetly dismantled by government officials, while in others, violent gangs of vengeful and nationalist-oriented youthful men took matters into their own hands, frequently participating in clashes with pro-Soviet people.

The fate of the Lenin sculptures is a fascinating element of modern Ukrainian history.

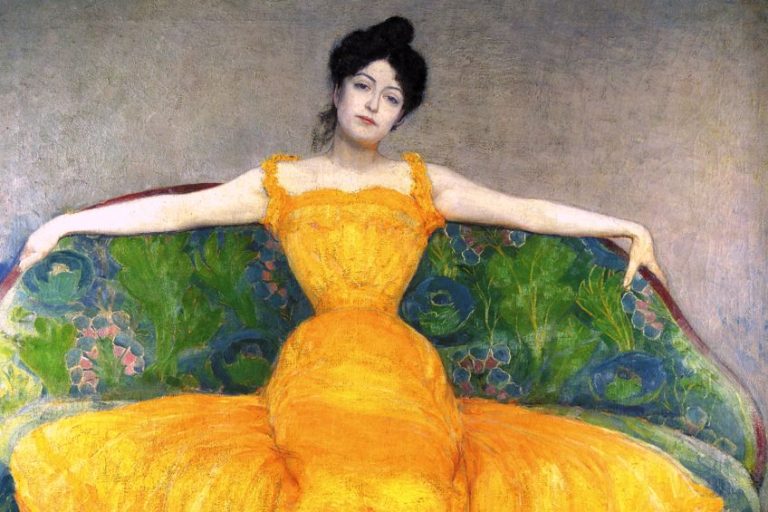

Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez

This painting was intentionally attacked with an ax as an act of protest, for what the attacker considered lewd glances from the men who viewed it. Vandalism is frequently viewed as irrational, savage, and lacking a clear cause. Iconoclasm, on the other hand, may be understood as a historically legitimate act of violence against art since it is concentrated on the practice of worship instead of the damage to property.

Acts of violence towards art consist of two steps: an assault on the actual art item and an onslaught on the emblem, symbol, or sign that the art object symbolizes.

Fountain of Justice (Bern – Switzerland)

A beautiful statue that was toppled by members of a radical group. The monument was taken down with a rope on October 13, 1986. The collapse entirely obliterated it. Nobody claimed responsibility for the incident, although it was widely connected to the Groupe Bélier, a violent young organization promoting Jurassic secession.

Only one individual has ever been charged with the statue’s demolition. Since the incident, the destroyed sculpture has been restored at the city’s historical museum.

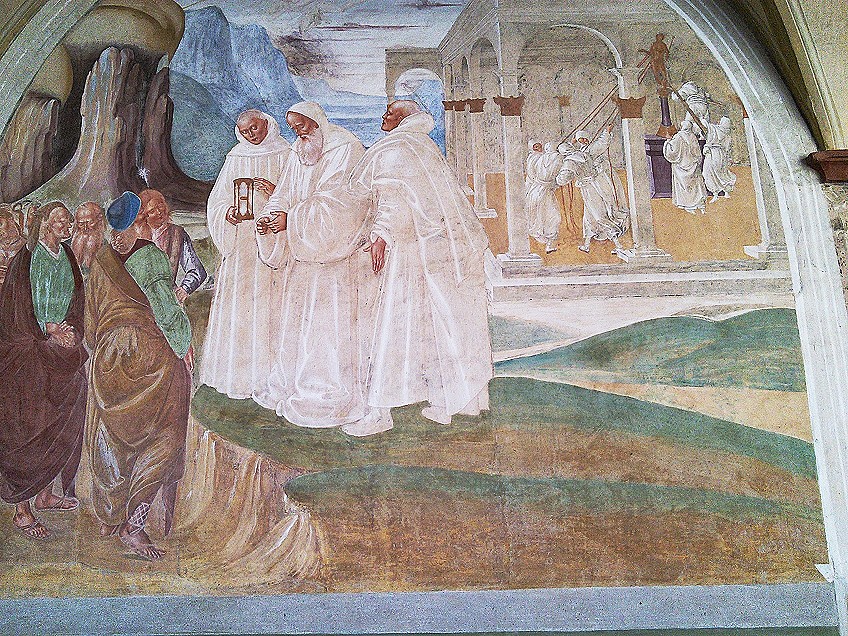

The Apse Mosaic of the Church of Dormition (Iznik, Turkey)

This mosaic underwent several changes over various periods, with the mother and child image being replaced by a cross and then reverted again later due to changing religious trends. The iconoclasts maintained that because God was unseen and limitless, he could not be represented in images. The iconoclasts maintained that because Jesus was God in human form, he could not be shown in pictures.

While the iconoclasts rejected some sorts of iconography, they did not completely dismiss art, and some, like Constantine V, were great supporters of architecture and art.

In this article, we have discussed the history of icons throughout the ages, including Byzantine icons and their destruction. Iconoclasts are those who argue that firmly held beliefs or established institutions are based on ignorance or superstitions. Iconoclasm may also refer to campaigns for massive damage of symbols of an idea or cause outside of the religious setting, such as the demolition of monarchist emblems during the French Revolution, as well as the Communist rebellions in Russia and China.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Iconoclasm?

Iconoclasm is the societal notion that it is important to destroy icons and other pictures or monuments, usually for political or religious purposes. Iconoclasts are anyone who participates in or supports iconoclasm, a word that has come to be extended figuratively to anybody who opposes cherished ideas or respected structures on the basis that they are erroneous or destructive.

What Is the Iconoclastic Meaning?

While members of a different faith may commit iconoclasm, it is most usually the outcome of sectarian disagreements between groups of the same church. The name derives from Byzantine Iconoclasm, a conflict in the Byzantine Empire between supporters and opponents of religious images. Iconoclasm varies significantly amongst faiths and their branches but is highest in religions that abhor idolatry, such as the Abrahamic religions.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Iconoclasm – Looking at the History of Icons in Iconoclasm Art.” Art in Context. April 4, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/iconoclasm/

Meyer, I. (2022, 4 April). Iconoclasm – Looking at the History of Icons in Iconoclasm Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/iconoclasm/

Meyer, Isabella. “Iconoclasm – Looking at the History of Icons in Iconoclasm Art.” Art in Context, April 4, 2022. https://artincontext.org/iconoclasm/.