Negritude Movement – The History of the Negritude Movement

What was the Negritude movement and what was its impact on society? Negritude was a literary movement that arose out of the intellectual atmosphere of Paris in the 1930s and 1940s. It was the result of black writers working together to express their cultural identity through the use of the French language. To learn more about this fascinating movement, read below as we explore everything you need to know about the Negritude movement, including examples of Negritude poems, art, music, and notable individuals.

What Was the Negritude Movement About?

The Negritude movement arose in response to black people’s historically alienated position in society. The movement developed a unique identity for black people all across the world and it also played a crucial role in the rejection of colonialism. It emerged on the brink of African liberation movements and had an influence on how those that were colonized perceived themselves.

It also inspired subsequent literary movements that arose in response to world politics. The Negritude movement has no definite end date, and some literary critics argue that it persists even today in any form of artistic expression that emphasizes black identity. The Harlem Renaissance and Surrealism were among the styles and art movements that influenced those working within the movement. It became a worldwide art movement at the onset of World War II as its intellectuals and artists dispersed from Paris.

The Origins of the Negritude Movement

Paris, with its liberal and diversified art environment, became the international Negritude movement’s center in 1937. Faced with a rise in fascism, black students, artists, and intellectuals from French colonies in the Caribbean and Africa joined together to promote an understanding of black culture and history. They also aimed to call attention to individuals who were under colonial control, including slaves. When the Second World War broke out, its leaders fled to the Caribbean and Africa, where new manifestations of Negritude emerged, notably the Natural Synthesis movement in Nigeria and Creolization in the Caribbean. After the war, though, Paris became the epicenter of Negritude activity once again.

Many African and Caribbean artists traveled to Europe to study and were drawn to Paris, where they met at the Left Bank’s Negritude base and the Clamart tea shop.

The Negritude Movement’s Founders

Negritude artists embraced ideas and characteristics borrowed from a variety of sources to criticize imperialism and to create a new internationally-recognized avant-garde movement. As with all movements, the Negritude movement’s development can be traced back to the work of a handful of influential individuals. In the chapter below, we will examine a few of the most noteworthy pioneers of the Negritude movement.

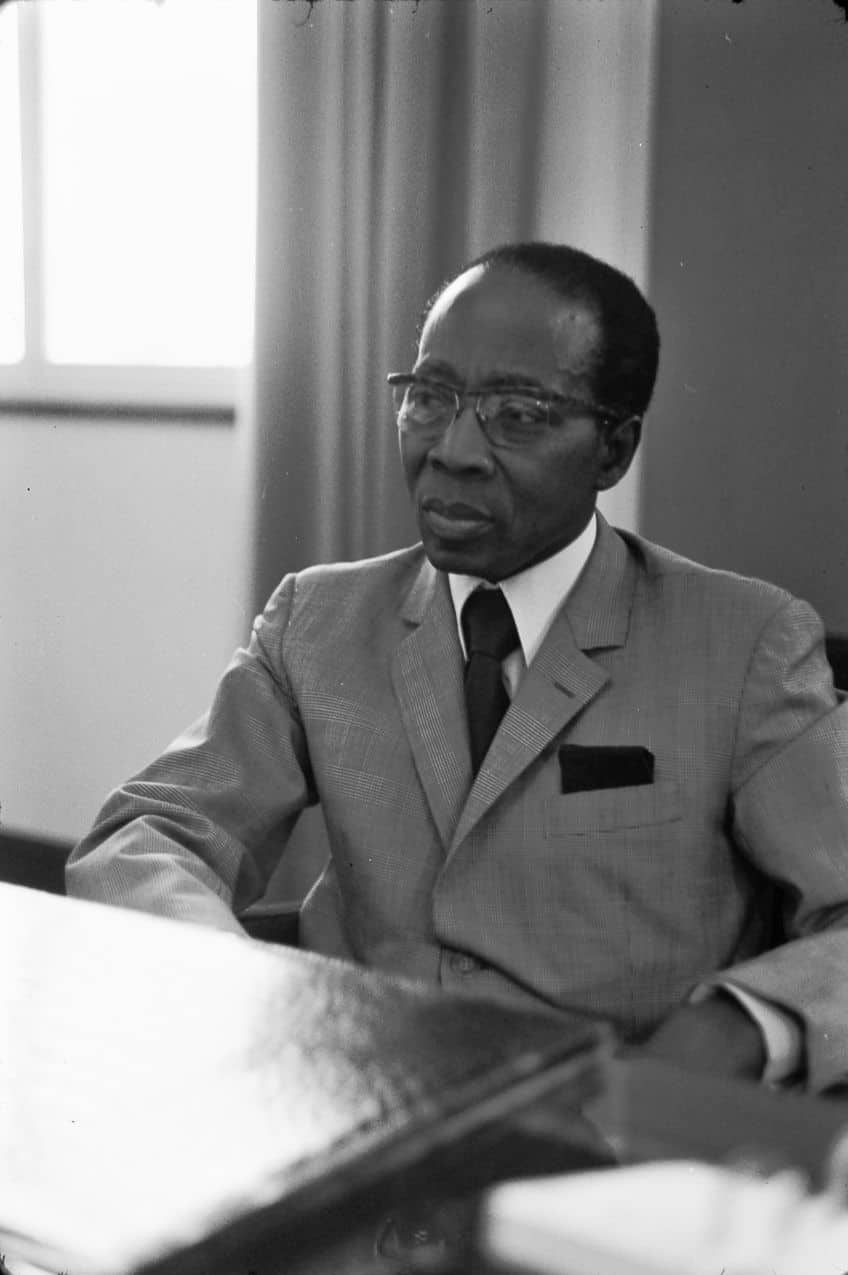

Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906 – 2001)

| Full Name | Léopold Sédar Senghor |

| Nationality | Senegalese |

| Date of Birth | 9 October 1906 |

| Date of Death | 20 December 2001 |

| Place of Birth | Joal Fadiout, Senegal |

Léopold Senghor was Senegal’s president from 1960 to 1980, as well as a poet and pioneer of the Negritude movement in African literature and art. He finished his studies and worked as a teacher in Paris. After having been drafted into the French army in 1939, he was caught and imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps for two years, where he composed some of the best examples of Negritude poems ever created. Senghor became an internationally acclaimed advocate for Africa and the Third World after promoting a moderate “African socialism” devoid of extreme materialism and atheism.

He was the very first black person to be accepted into the French Academy in 1984.

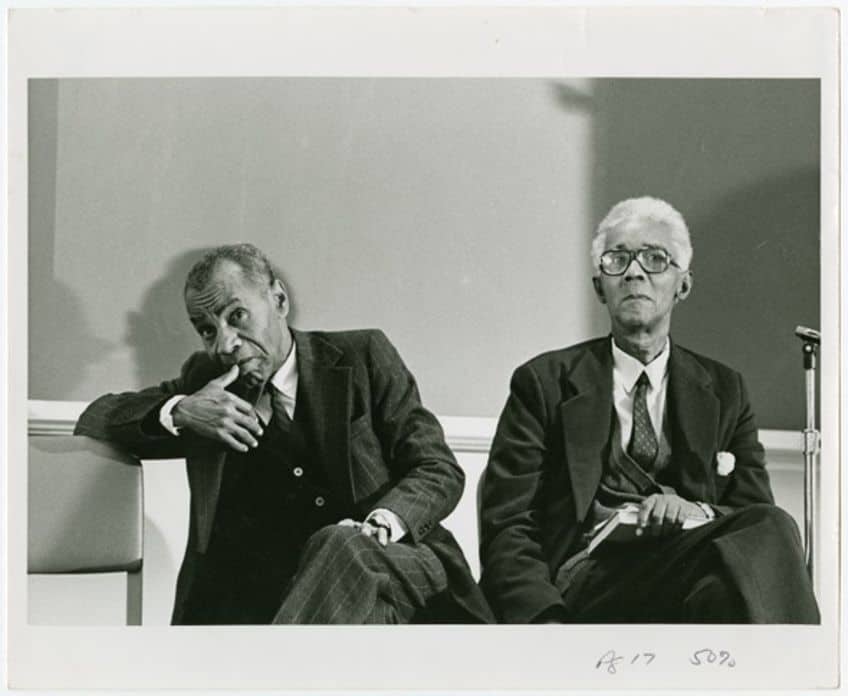

Léon-Gontran Damas (1912 – 1978)

| Full Name | Léon-Gontran Damas |

| Nationality | French |

| Date of Birth | 28 March 1912 |

| Date of Death | 22 January 1978 |

| Place of Birth | Cayenne, French Guiana |

Despite being less well-known than Senghor and Césaire, Damas was seen as a major influence by other black poets; he was one of the first poets working in a language apart from English to convey a unique black consciousness. Damas was highly affected by African-American music and poetry, and he eventually relocated to the United States. Damas appeared to be on course for financial success after being accepted to law school in Paris. Yet, Damas felt alienated in France and started to seek solace in his own cultural heritage.

He was influenced by a wide range of concepts, including anti-colonialist manifestos, surrealist art, and an interest in the African-American culture that was spreading across Paris at that time.

Aimé Césaire (1913 – 2008)

| Full Name | Aimé Fernand David Césaire |

| Nationality | French-Martinican |

| Date of Birth | 26 June 1913 |

| Date of Death | 17 April 2008 |

| Place of Birth | Basse-Pointe, Martinique Island |

Negritude was co-founded by Aimé Césaire, a Martinican writer, poet, and politician. Césaire was educated in Paris with Senghor and other members of the Negritude movement. In the early 1940s, he relocated to Martinique and became involved in political activity in support of the independence of French African territories. He joined the Communist Party after seeing the plight of black people as merely one component of the class struggle.

He discovered that Surrealism, which liberated him from traditional forms of language, was the most effective way to communicate his beliefs. He expressed his fervent resistance in a French infused with African imagery.

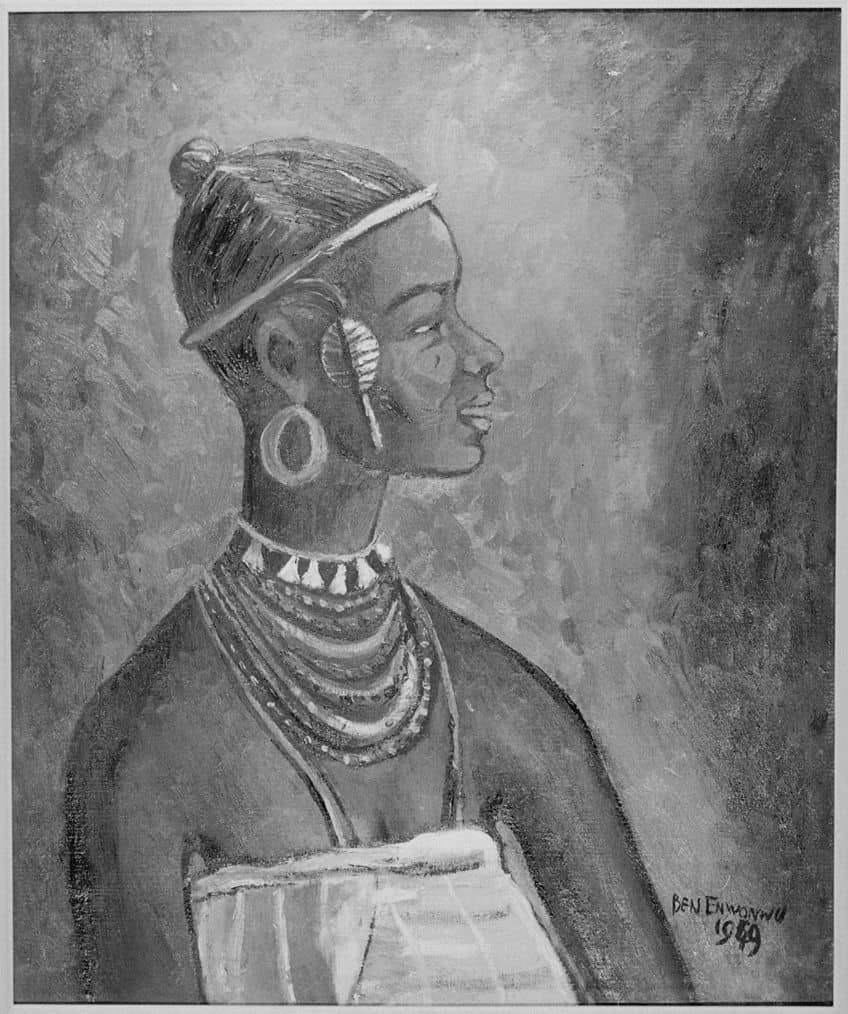

The Principles of the Negritude Movement

Léopold Sédar Senghor, one of the movement’s most important voices, said in 1956 that for black culture to move beyond its past and represent modernity, it must honor its own traditions while being open to new ideas and innovations in art. Artist Ben Enwonwu stated it clearly in a significant piece published the same year in the journal Présence Africaine. He contended that, while West African culture was viewed through the lenses of anthropology and ethnography, and African art was characterized as primitive, there was an “intellectual barrier” that made it very hard for most Africans to be regarded as qualified to serve an important role in the growth and conservation of their art.

He advocated for worldwide African art that responded to modern life and times while also being conscious of local, traditional, and global influences.

Senghor organized the World Festival of Negro Arts in 1966. This was the first time that many black musicians, artists, authors, poets, and performers had the opportunity to engage in a global exploration of African culture. Senghor saw the event as his first opportunity to advocate Negritude principles as a valid philosophical model. The event also provided an opportunity for a complex reassessment of African tribal artwork, which had previously been treated with disdain by the African diaspora. Tribal art was to be regarded as art for the first time in Africa. The festival sparked the birth of the international black arts movement. Here are a few of the fundamental principles of Negritude.

Embracing Black Identity

Embracing black identity is regarded as a fundamental Negritude principle. It encourages African-Americans to celebrate their history and traditions. Negritude maintains that blackness is a rich and meaningful identity worthy of respect and appreciation, rather than something to feel a sense of inferiority from. Individuals learn to develop a sense of pride in their heritage by embracing their black identity.

Rejection of Colonialism

Another significant principle of Negritude is the rejection of racism and colonialism. It originated as a reaction to the severely oppressive institutions of European colonization and the racism that pervaded colonial-influenced countries. Negritude criticized mainstream Eurocentric narratives that depicted Africans as well as individuals of African heritage as inferior or primitive.

It tried to undo the psychological and cultural legacies of colonialism by reinforcing the value of black people in society.

The Promotion of Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a global movement that promotes the unity of people of African heritage. Those within the Negritude movement acknowledged that black people’s hardships were not isolated episodes, but rather interrelated experiences resulting from a common past of imperialism and racism. Negritude sought to promote a feeling of collective identity as well as collaboration among black communities in order to overcome common obstacles and achieve independence from repressive institutions.

Negritude Movement Literature

Young black students and intellectuals from France’s colonies and territories gathered in Paris during the 1920s and 1930s, where they were introduced to Harlem Renaissance authors such as Claude McKay and Langston Hughes, as well as Paulette Nardal and her sister, Jane. The Nardal sisters participated in the Negritude debates through their works and also ran the Clamart Salon, an Afro-French intellectual tea shop where the philosophies of Negritude were regularly discussed. Paulette Nardal founded La Revue du Monde Noir, a literary publication printed in French and English that sought to reach out to Caribbean and African intellectuals in Paris.

The concurrent emergence of negrismo and embrace of “double consciousness” in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean region shared this Harlem influence.

Negritude Poetry

Because French colonization had a huge effect on many Caribbean and African nations, negritude poets regularly composed in French. They did, however, imbue their works with aspects of their diverse linguistic and cultural origins, including elements of African oral traditions, local dialects, and folklore. Negritude poets aspired to restore and communicate the importance of black people through their many examples of Negritude poems, while at the same time criticizing restrictive institutions that sought to marginalize them.

The strong and evocative poetry of Aimé Césaire demonstrates a profound sense of pride in African history as well as an aching desire for emancipation from colonial tyranny. His art celebrates the diversity of African culture while exploring topics of exile, identity, and resistance. Negritude poetry spans a wide range of forms and subjects, but it generally shares one thing in common: it celebrates blackness.

Negritude Novels

Negritude novels, as with their counterparts in poetry, strove to offer alternate viewpoints on the African experience than those that were prominent in the public sphere at that time. Amadou Hampâté Bâ, a Guinean author, is a significant figure in Negritude literature. While he is most known for his nonfiction, his book The Fortunes of Wangrin is regarded as an important contribution to Negritude literature.

Set in colonial-era West Africa, the novel depicts the complicated daily life of Wangrin, the book’s main character as he deals with the complexities of identity, power, and survival in an ever-changing culture.

Ousmane Sembène, a Senegalese filmmaker and author, is another important writer linked with Negritude. Sembène’s books powerfully illustrate the hardships of African communities under colonial control. His novels address issues of cultural identity, resistance, and the political and social consequences of colonization.

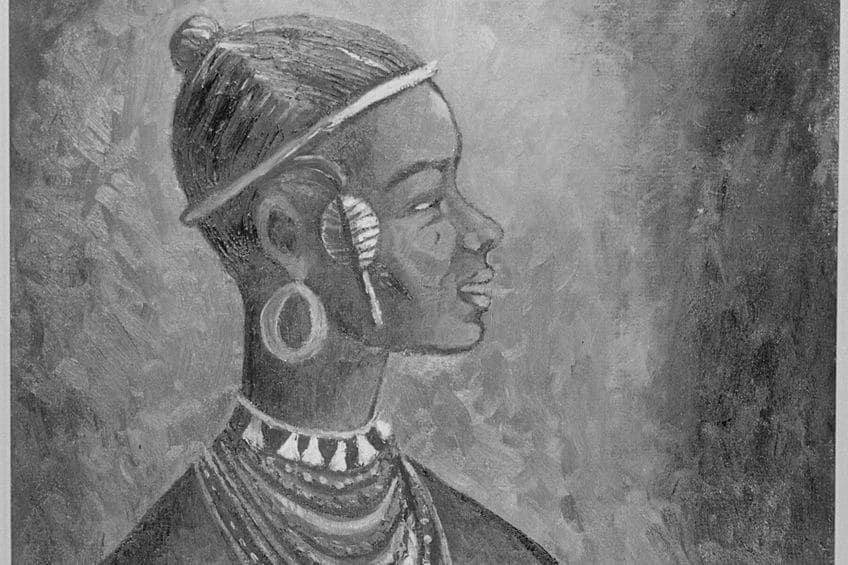

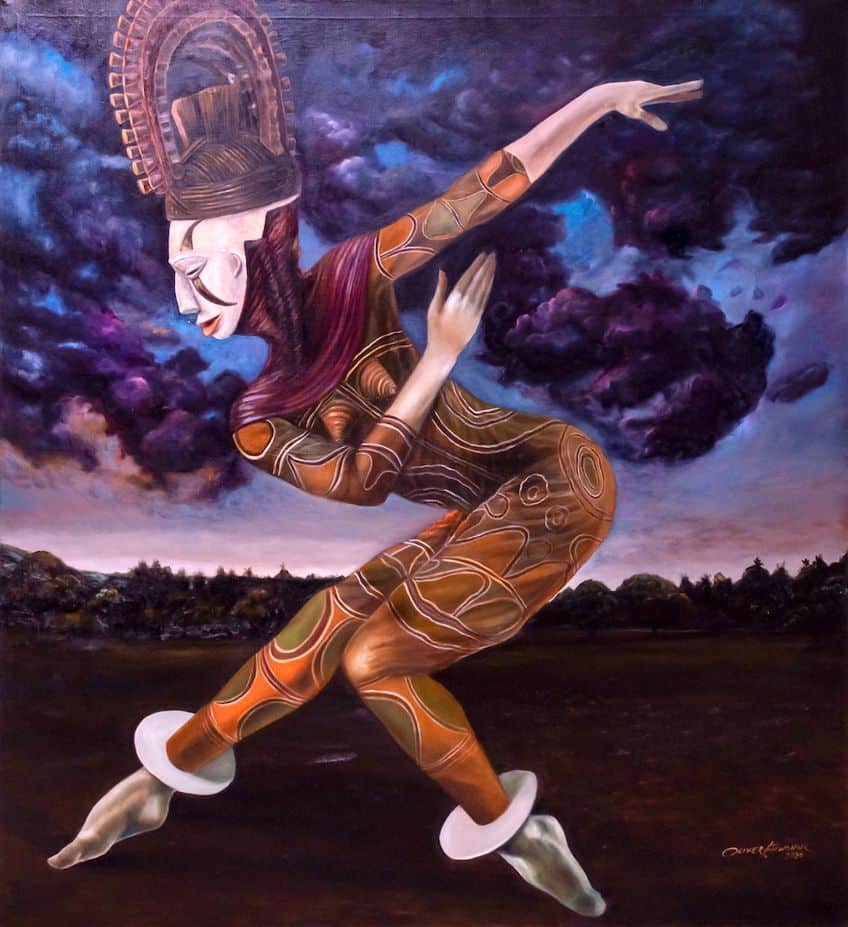

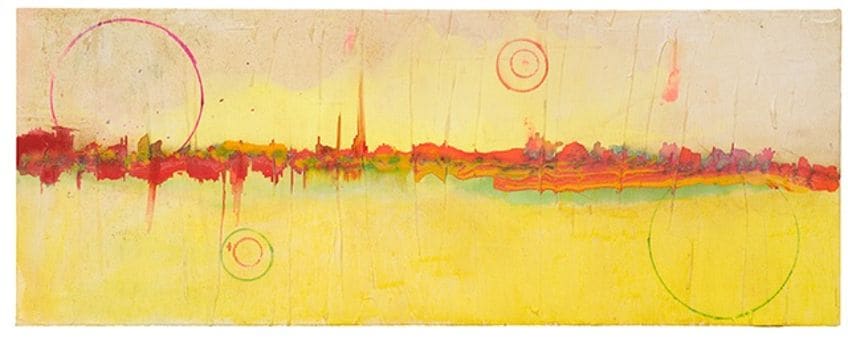

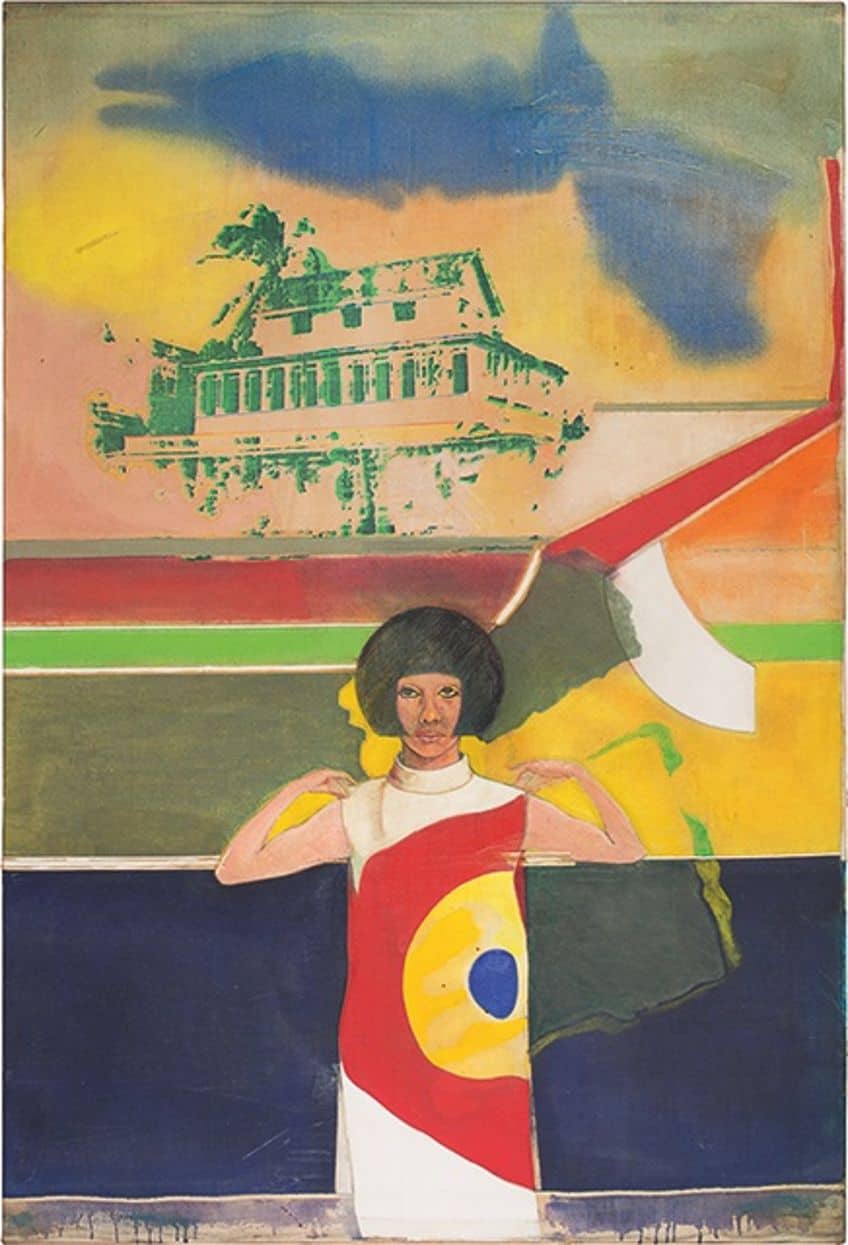

Negritude Art

Negritude Art often incorporates aspects of African art symbolism and aesthetics. Negritude artists wanted to challenge mainstream Eurocentric aesthetic standards and depictions of blackness, which were typically stereotyped, exoticized, or degrading. Negritude Art also had an impact on the formation of modern African art movements such as African modernism and the subsequent Black Arts and Afrocentric movements. These groups carried on the tradition of Negritude Art by exploring issues of black identity through diverse art forms. The Sudanese artist, Ibrahim El-Salahi, who used African symbolic imagery and calligraphy in his pieces, and the Cuban Wifredo Lam, who blended aspects of Caribbean, African, and European art to produce distinct visual depictions of the African diaspora, are two artists connected with Negritude Art.

Negritude Music

Negritude music is inspired by numerous musical traditions based in the Caribbean, Africa, and other African diaspora-influenced locations. It combines African rhythms, melodies, and instruments with regional musical influences. Negritude music is used for cultural preservation and expression. Afrobeat is a popular genre linked with Negritude music. Afrobeat is a kind of music that originated in Nigeria in the 1960s and was popularized by artist Fela Kuti.

It incorporates highlife music, funk, jazz, and indigenous West African rhythms.

It honors African history and advocates for Pan-African unity and freedom. Reggae music, which originated in Jamaica, has played an important impact on Negritude music. Reggae artists like Bob Marley utilized the genre as a platform to discuss issues such as social justice, injustice, and the challenges of the African diaspora. The sentiments of empowerment and liberty in Reggae music resonated with the principles of the Negritude movement.

The Dissemination of the Negritude Principles

Negritude extended around the globe through multiple paths and events, growing in popularity and influence in the Caribbean, Africa, and France. The spread of the movement traces back to significant individuals’ efforts, literary publications, artistic partnerships, and the larger cultural and intellectual context of the period. The Negritude movement flourished throughout Africa, where authors, scholars, and artists tried to recover and proclaim their African identity.

African intellectuals such as Léopold Sédar Senghor and Cheikh Anta Diop were instrumental in spreading the principles of the Negritude movement. They founded cultural and literary groups, attended international conferences, and wrote important pieces about African emancipation. The concepts were spread through literary academic institutions and literary publications, subsequently influencing a new generation of African authors, activists, artists, and musicians.

The Caribbean, particularly French-speaking countries such as Guadeloupe and Martinique, was fundamental in the formation and spread of the Negritude movement’s ideals. René Depestre and Frantz Fanon, among others, played an important role in the intellectual and literary conversation about Negritude. The history of racial persecution and the diversity of culture in the Caribbean presented the ideal setting for the examination of the black sense of self.

Because of its colonial influence and location as a center of intellectual and cultural movements, France played an important role in the spread of the Negritude movement. It flourished because of the Caribbean and African intellectuals who went to France for study and cultural exchange. Literary meetings, salons, and creative collaborations in Paris offered Negritude authors and artists an ideal environment in which to discuss their writings and beliefs.

Publishing houses played an important role in promoting Negritude literature and fostering cultural interchange between French and African intellectuals.

Criticisms of the Negritude Movement

One critique raised about Negritude is that it essentializes black identity, portraying it as a uniform and unchanging construct. Some critics state that Negritude’s focus on a fundamental “blackness” essentially ignores the multiplicity and complexities of the various black lives that exist out there. They argue that this essentialist perspective may actually unintentionally propagate stereotypes or overlook the uniqueness and cultural subtleties that can be found in black communities across the world. Instead, they push for a more nuanced perspective of black identities that takes into account class, race, gender, and other such factors.

Another common critique is that the Negritude movement concentrated exclusively on racism and colonialism while failing to effectively address gender issues. Some claim that Negritude usually cast black women in traditional roles or ignored the unique issues that women experience in black communities. Some say that the Negritude movement’s emphasis on a communal black identity ended up obscuring black women’s particular experiences and problems, resulting in them being marginalized within the larger Negritude discourse. Scholars have therefore advocated for a more inclusive approach to addressing the complexities of gender in the context of racism.

The Legacy of the Negritude Movement

While these criticisms may be valid, the Negritude movement was also a catalyst for future movements and interactions that attempted to solve these concerns. Post-Negritude artists, authors, and activists have expanded on those initial concepts, including intersectional viewpoints and delving into the nuances of black identities. These continuous discussions reflect the ever-changing nature of philosophical and cultural movements, as well as the need to address the various facets of social justice.

Negritude was an early example and source of inspiration for black consciousness groups that arose in the 1960s and 1970s.

These early movements such as the American Black Arts Movement, as well as the broader Black Power and Pan-African movements, drew on the Negritude movement’s principles and ethos. They sought to oppose white dominance, encourage self-determination, embrace black culture, and instill pride and solidarity among individuals of African heritage.

Negritude made an important contribution to the field of postcolonial studies. Its criticism of colonialism, focus on cultural reclamation, and investigation of power dynamics laid the groundwork for the studies that followed. The celebration of black culture, rejection of colonial narratives, and advocacy of cultural pride promoted by the Negritude movement also significantly impacted future artistic movements. The ideals of the movement influenced the creation of African film, Afrofuturism, Afrobeat music, and numerous contemporary art movements.

That completes our look at the Negritude movement. As a response to French colonial racism, the Negritude authors found camaraderie in a shared black identity. They believed that the African diaspora’s shared black ancestry was the finest weapon they had for combating French social and intellectual dominance and supremacy. The Harlem Renaissance, notably the output of African-American authors Richard Wright and Langston Hughes, whose writings explore the issues of “blackness” and racism, significantly impacted the movement. Further influence came from Haiti, where black culture flourished in the early 20th century, and which historically occupies a special position in the African diaspora as a result of the slave revolution.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Participated in the Negritude Movement?

Aimé Césaire, a Martinique writer, poet, and politician, studied in Paris, where he encountered the Black community and rediscovered the African spirit. Léopold Sédar Senghor, Senegal’s first president, utilized the movement to spread the universal message of the value of African individuals. While he supported the dissemination and celebration of ancient African practices in spirit, he opposed returning to old approaches to doing things. This interpretation of the movement’s principles was the most widespread, especially later on. Aimé Césaire and Suzanne, his wife, would go on to become important Caribbean Surrealist authors, revered by Andre Breton, the Surrealist leader.

Where Did the Negritude Movement Start?

During the 1930s, the Negritude movement began in the French-speaking Caribbean, notably in the French overseas territories of Guadeloupe and Martinique. While the movement began in the Caribbean, it rapidly extended to other Francophone countries, notably Africa, where authors and thinkers welcomed and incorporated its values into their own writings. As a consequence, Negritude grew into a global movement, connecting with individuals of African heritage all over the world striving to question colonial narratives, establish their sense of culture, and achieve political and social independence.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Negritude Movement – The History of the Negritude Movement.” Art in Context. July 17, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/negritude-movement/

Meyer, I. (2023, 17 July). Negritude Movement – The History of the Negritude Movement. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/negritude-movement/

Meyer, Isabella. “Negritude Movement – The History of the Negritude Movement.” Art in Context, July 17, 2023. https://artincontext.org/negritude-movement/.