“Colossus of Rhodes” – The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

One of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Colossus of Rhodes statue once stood proudly at the entrance of the Rhodes town harbor. A massive structure such as the Colossus statue must have been an incredible sight to behold in its time, yet nothing remains of it today, which makes one wonder what happened to the Colossus of Rhodes. Once you have explored all the Colossus of Rhodes facts in this article, you will know the answer to several questions such as “Why was the Colossus of Rhodes built?” and “How big was the Colossus of Rhodes?”

The Colossus of Rhodes Facts

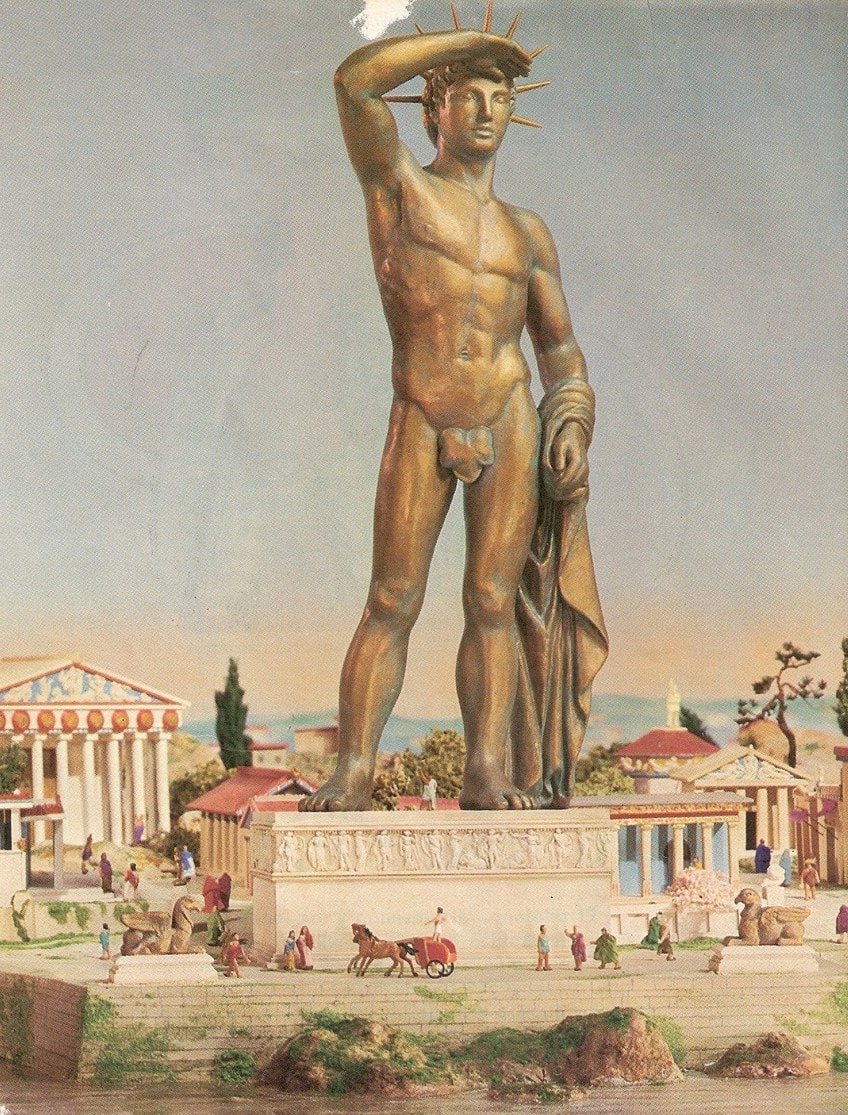

Counted among the Seven Wonders, the Colossus of Rhodes was a huge and impressive monument created to celebrate a victory that occurred centuries ago on the Greek island of Rhodes. The Colossus statue was constructed as a symbol of the island inhabitant’s successful defenses against the Macedonian military leader Demetrius Poliocretes, who for more than a year, had terrorized the islanders with his naval and army forces. Based on descriptions currently available, the Colossus of Rhodes was roughly equivalent in size to the modern Statue of Liberty (1876), at around 33 meters – making it the largest of the ancient world’s statues.

An earthquake was the cause of the “Colossus” statue’s ultimate demise, which occurred in 226 BC, but there were recovered parts that were preserved at the time.

The local islanders were even dubbed Colossaeans by foreigners due to the widespread fame of the Colossus statue. By the time Muawiyah I, an Arabian general, had overthrown the local Rhodian rulers in 653 AD, it was reported that nothing remained of the legendary Seven Wonders of the Ancient World statue. Due to the popularity of the Colossus statue, there have been several proposals to rebuild it since 2008. However, one contentious element of the entire proposal remains standing in their way: exactly where was the statue of the Seven Wonders, Colossus of Rhodes, originally located in the harbor?

The History of the Famous Colossus of Rhodes Statue

The island of Rhodes was seen as an extremely significant region, as with its large naval forces and tactically advantageous location, it controlled who was able to gain entry into the Aegean Sea. To safeguard the trade route, Rhodes established neutrality agreements with neighboring nations. However, they had strong ties with Ptolemy I, and Demetrius Poliocretes was concerned that the Rhodians might provide him with ships.

Poliocretes also envisioned Rhodes being utilized as a potential headquarters for his operations, and this fueled his intentions of besieging the island.

The Siege of Rhode Island

The majority of the Greek community, whether Demetrius’ supporters or not, saw the invasion as an illegitimate raid of the island, and felt sympathy for the Rhodian people, and this sentiment was shared even among the Macedonians. Poliocretes enlisted the help of various pirate ships in addition to a naval fleet of more than 200 war vessels. More than 1,000 private merchant ships tailed his forces in expectation of the wealth his victories would provide.

The island’s harbor and town were well secured and Poliocretes was incapable of preventing supply ships from bypassing his blockade of ships, so seizing the harbor became his primary objective. He initially constructed a second harbor beside the existing one and excavated a trench from which he launched a floating boom, yet he was still never able to seize the harbor.

Meanwhile, his forces decimated the island and established a massive camp near the town yet out of striking range.

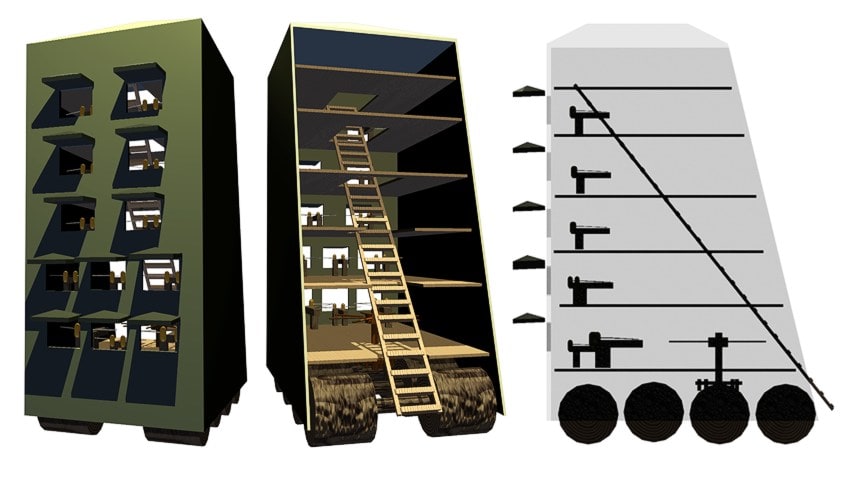

The town’s fortifications were penetrated early in the invasion, and a handful of men had managed to enter the city; however, they were all murdered, so Poliocretes did not advance his attack any further and the walls were later restored. During the assault, both sides deployed a variety of technological measures, including mines and counter-mines, as well as numerous blockade devices. In his effort to seize the city, Poliocretes even erected the now-famous siege tower named the Helepolis.

The Rhodians were effective in defeating Poliocretes; after around a year, he withdrew the blockade and negotiated a peace treaty in 304 BC, which Poliocretes hailed as a success since Rhodes consented to remain impartial in his conflict with Egypt.

The siege’s notoriety may have played a role in its termination after just 12 months.

Many years later, the deserted Helepolis had its metal covering smelted, and the proceeds from selling the remnants of Poliocrete’s equipment were utilized to create a monument of their sun deity, Helios, later called the Colossus of Rhodes, to honor their courageous defiance and victory.

Construction of the Colossus Statue

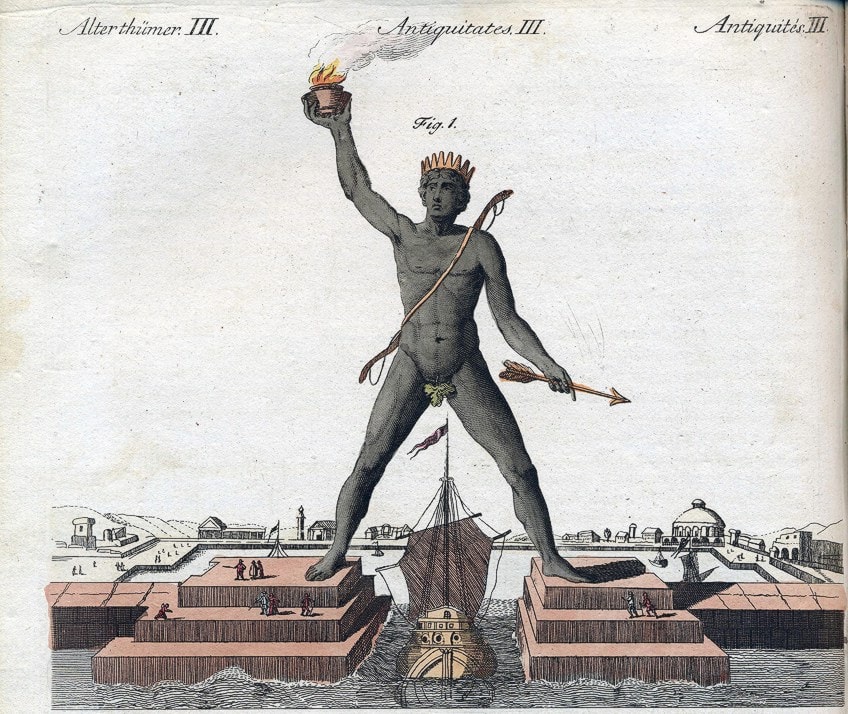

Construction of the Colossus statue started in 292 BC and according to historical reports, the edifice was created using iron tie rods to which brass sheets were attached to create the skin covering. As the building continued, the inside of the monument, which rested on a 15-meter-high marble platform overlooking the Rhodes port entry, was loaded with stone blocks. Other accounts situate the Colossus on a port breakwater barrier. Based on available contemporaneous records, the monument stood roughly 33 meters tall.

A significant amount of the bronze and iron was crafted from the numerous weapons left behind by Poliocrete’s army, and the discarded siege tower could have possibly served as scaffolding surrounding the lower floors during rebuilding.

Chares of Lindos, a student of sculptor Lysippus, was chosen to make this massive monument. Tragically, Chares of Lindos passed before the statue could be finished. Some claim he committed suicide, although this is most likely a myth. The precise method by which Chares of Lindos built such a massive monument is unknown. Some claim he erected an enormous earthen slope that grew in size as the monument grew higher. Contemporary designers, on the other hand, have discarded this notion as impractical.

It is believed that Chares produced the sculpture by having it cast in courses horizontally and then building a massive pile of rubble around each segment as they were completed, covering the completed work beneath the earth and then moving on to cast the next portion on the level.

However, modern engineers have also proposed their own viable explanations for the statue’s design, utilizing ancient engineering that was not dependent on modern seismic systems of engineering, and the descriptions of Philo and Pliny, who witnessed the remains personally and then documented them.

The foundation pedestal was believed to be approximately 18 meters across and perhaps round or octagonal in shape. The stone feet were coated with thin copper sheets glued together. The ankles were made using eight cast iron bars arranged in a radiated horizontal configuration and twisted upwards to follow the contours of the legs while growing gradually narrower.

Finely cast bronze plates with turned-in corners were riveted together to create a set of rings using holes produced during the casting process. Ursula Vedder, an archaeologist, has claimed that the monument was cast in big segments using typical Greek techniques and that Philo’s explanation is incompatible with the conditions demonstrated through the archaeology of ancient Greece.

Descriptions of the Seven Wonders’ Colossus of Rhodes

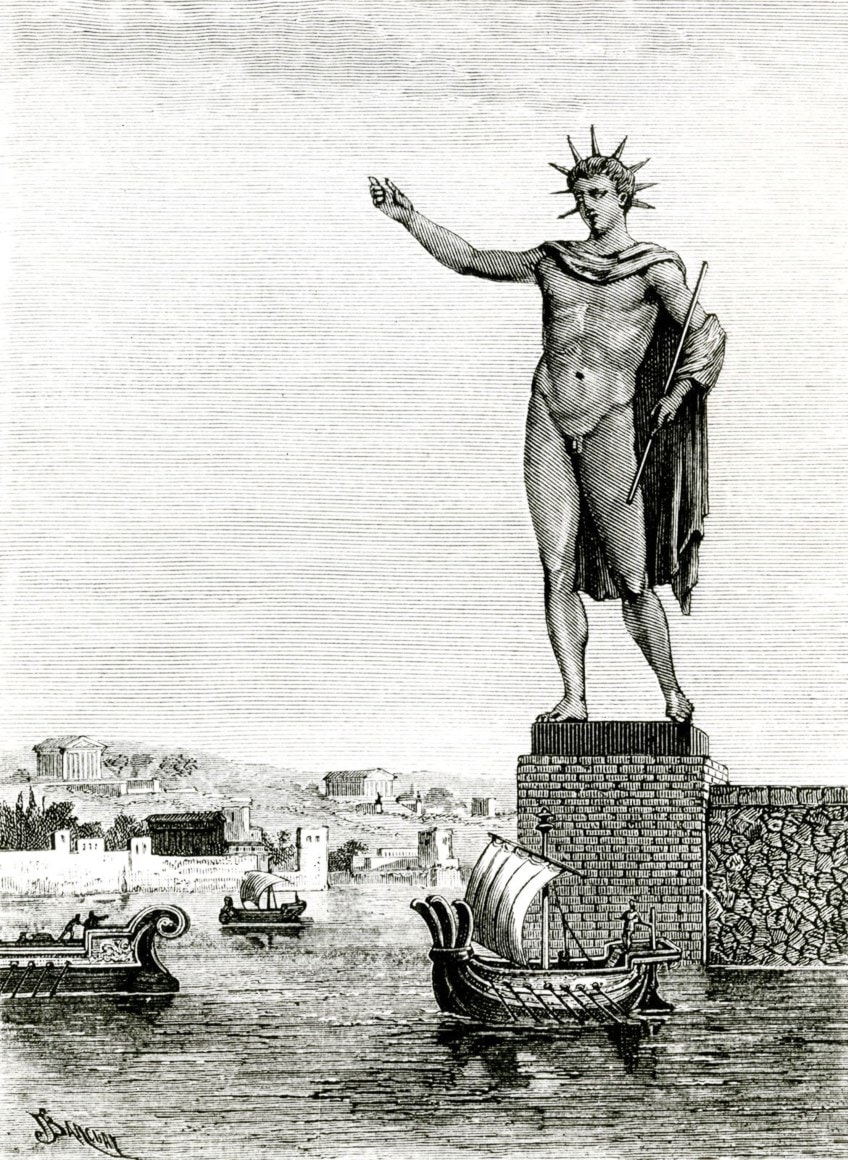

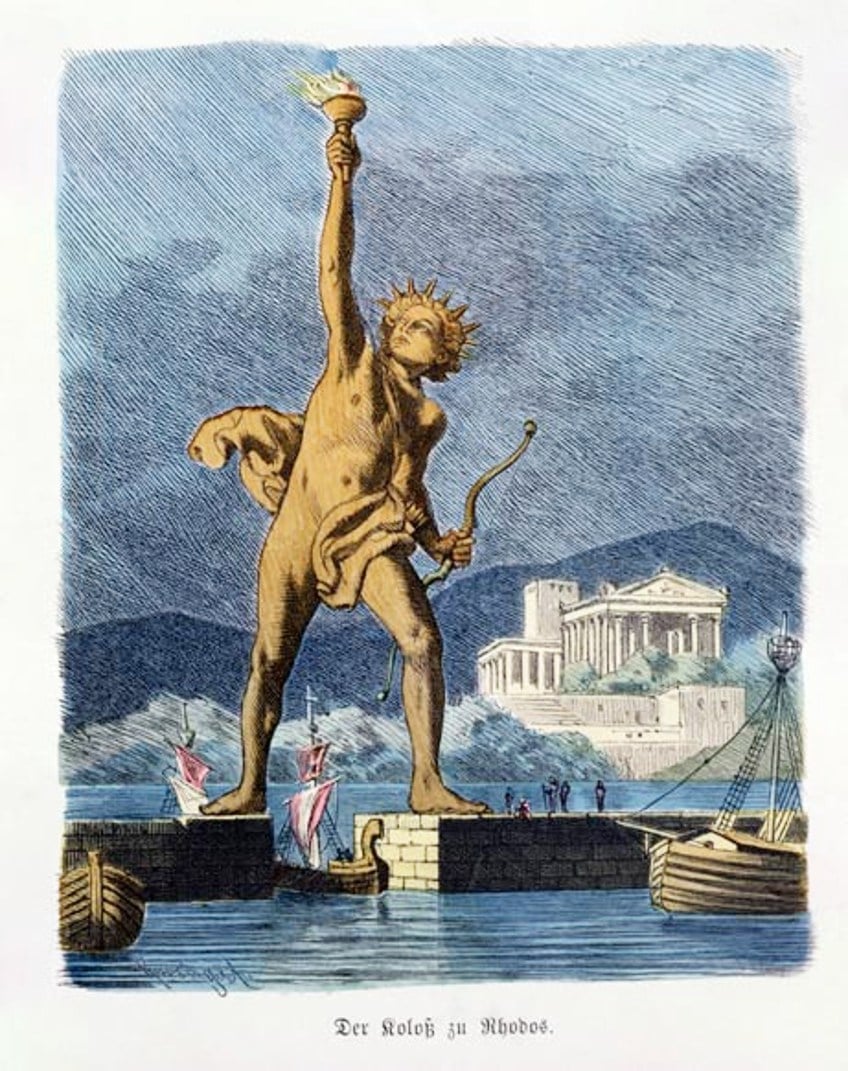

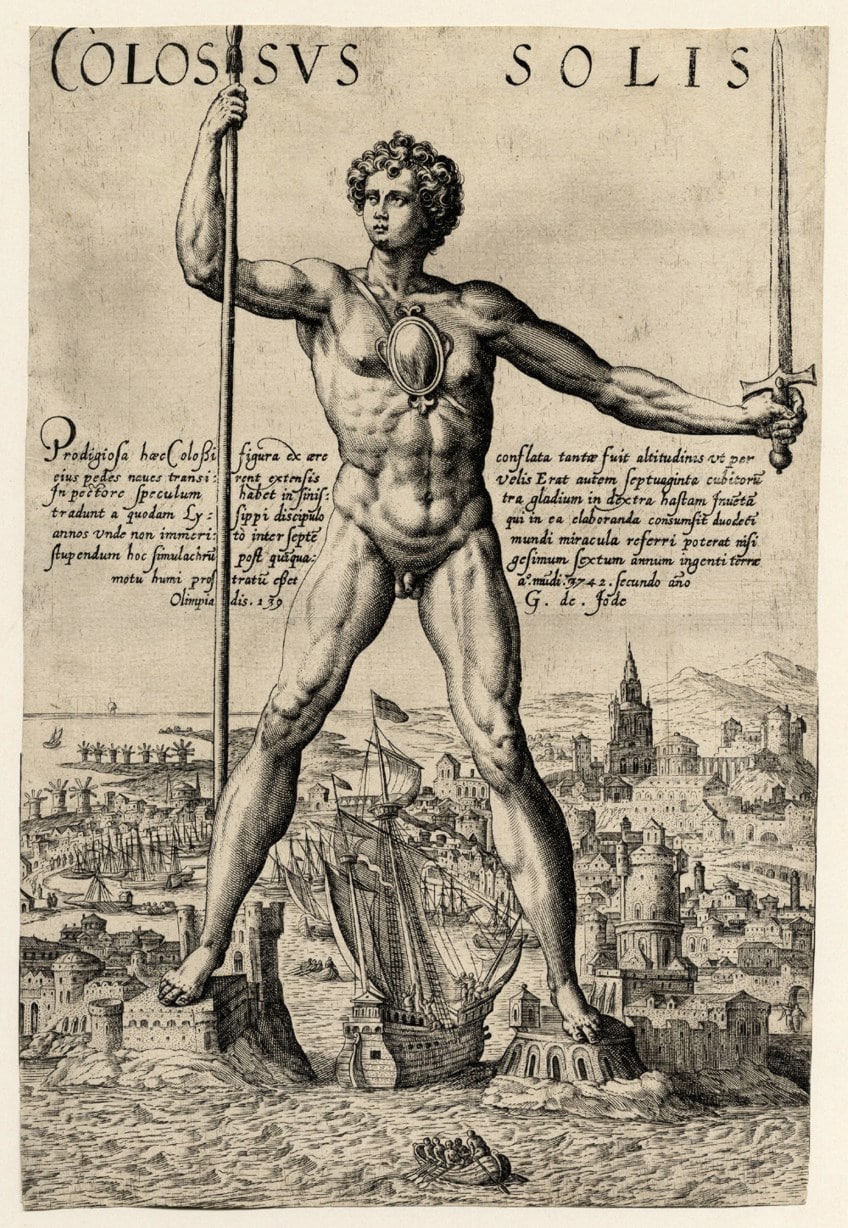

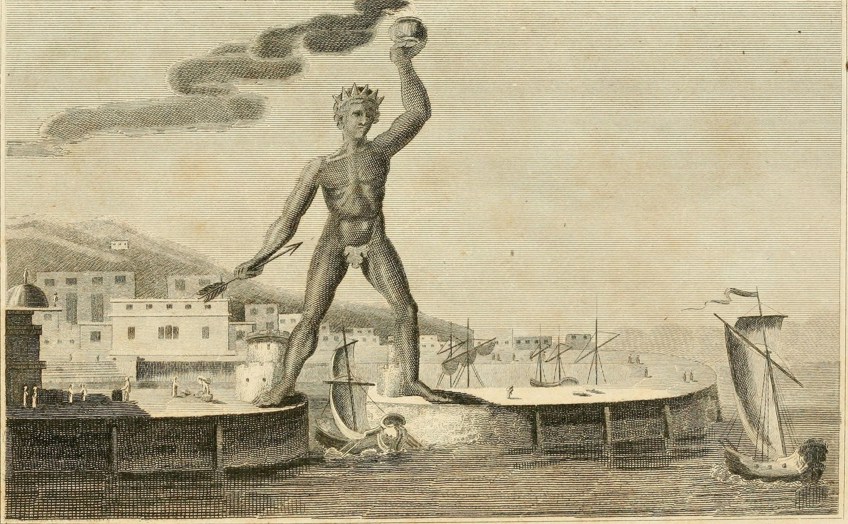

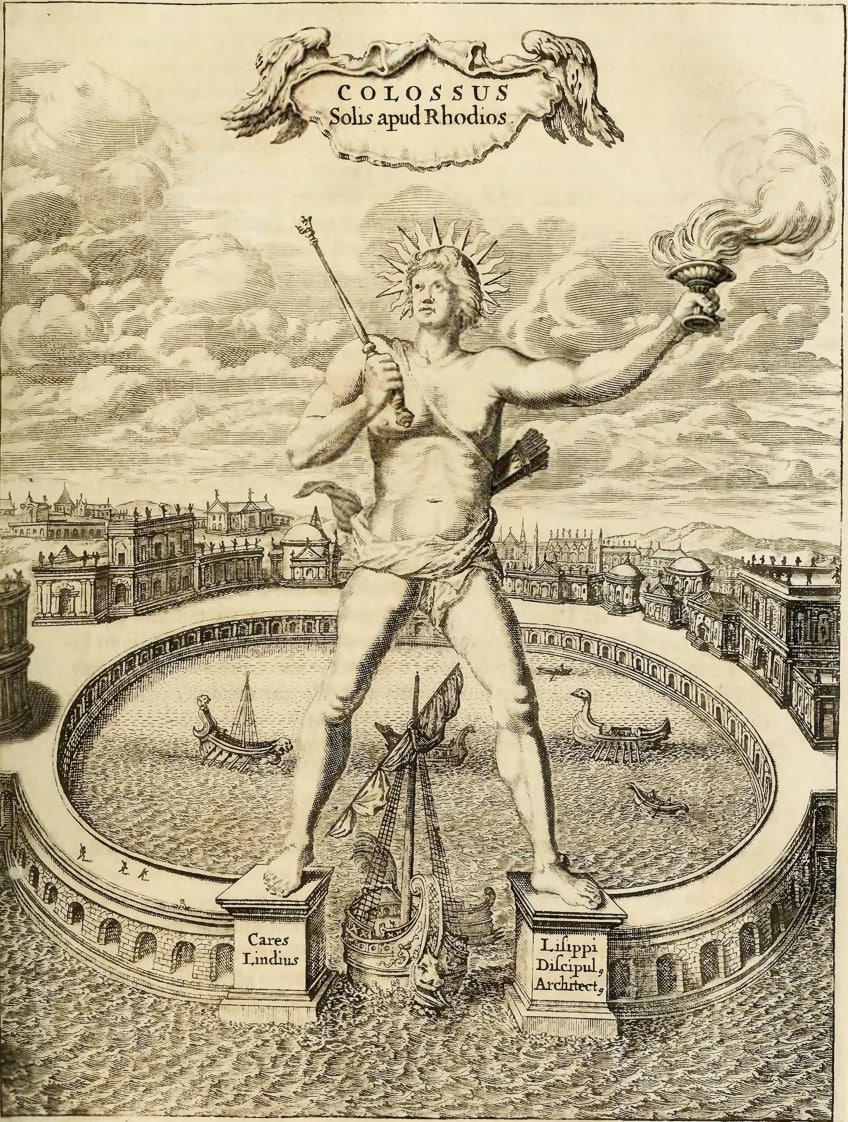

Predicated on the commemorative document’s reference to “over land and sea” multiple times and the manuscripts of an Italian traveler, it was believed that the statue’s right foot had originally been located where the church of St John of the Colossus was situated at that time. Many subsequent depictions portray the monument standing with a foot on each of the port mouth’s sides, with vessels passing beneath it.

While these spectacular depictions support the mythology, the facts of the circumstances demonstrate that the “Colossus” statue could not have been able to straddle the port.

If the finished monument had been positioned over the entrance, then the entire port’s entry would have been essentially blocked for the duration of the erection, and the Rhodians of that time period did not have the ability to excavate and re-open the port after completion. Furthermore, once the statue had fallen, it would have obstructed the port, and because the ancient Rhodians lacked the capacity to extract the collapsed monument from the wharf, it would not have been seen on the land and shoreline for the following 800 years, as previously described.

Even if these arguments were ignored, the monument was made of bronze, and mechanical studies demonstrate that it could not have been created with its legs standing apart without crumbling under its own weight. Many academics have discussed various sites for the monument that would have made constructing the monument by the ancients more plausible.

There is also no proof that the monument carried a torch overhead; the sources merely state that the Rhodians lit the “torch of freedom” once it was complete.

A fresco in a neighboring temple depicts Helios poised with one hand concealing his eyes, comparable to how a human covers their eyes while facing the sun, and the Colossus might have been built in the same posture. While historians have no knowledge of what the monument really looked like, researchers do know what the face and the head looked like because it was a normal representation at the time. The hair on the head would have been wavy, with uniformly scattered spikes of silver or bronze flames rising from it, comparable to the representations depicted on Rhodian currency presently.

Potential Locations for the Colossus of Rhodes

Although experts largely acknowledge that anecdotal descriptions of the Colossus flanking the harbor’s point of entry have no historical or scientific validity, the monument’s exact placement is unknown. As previously stated, the monument is believed to have been erected where two pillars currently exist at the Mandraki harbor entry. A circle of sandstone stones of unknown origin or use may be seen on the ground of the Fortress of St Nicholas, near the port entry.

Contoured blocks of marble used in the Fortress building (but thought to be too delicately cut to have been produced for that reason) have been proposed as the remains of a marble foundation for the statue, which would have been built atop the sandstone base.

The Colossus of Rhodes, according to some archaeologists, was not situated in the port region at all, instead, it was located at the Acropolis of Rhodes, which sat on a hill overlooking the harbor. At the peak of the hill, the remnants of a massive sanctuary, presumed to have been devoted to Apollo, may be found. Archeologists argue that the temple would have been a Helios shrine, with a piece of its massive stone base serving as a stabilizing foundation for the Colossus statue.

The Collapsed State of the Colossus Statue After the Earthquake

The monument remained where it stood for 54 years until an earthquake decimated vast expanses of Rhodes in 226 BC, along with the port and trade buildings. The monument cracked at the knees and plummeted onto the ground. Ptolemy III proposed to finance the statue’s repair, however, the oracle of Delphi convinced the people of Rhodes that they had angered the god Helios, therefore they refused to reconstruct it.

The remnants remained on the land for almost 800 years, despite the fact that they were fragmented, and were so magnificent that many people traveled just to view the ruins.

Strabo was a Greek explorer, historian, and philosopher who resided in Asia Minor amid the Roman Republic’s conversion into the Roman Empire. Strabo is most known for his book Geographica (1469), which gave a detailed account of individuals and events known within his lifetime from various areas of the world.

He provided a description stating that the Rhodian port was on the eastern point of Rhodes, and he found it to be greater than all others in docks, roadways, fortifications, and general developments that he couldn’t talk of any other city comparable to it.

He believed it was also notable for its adherence to the management of state affairs overall, and especially regarding naval matters, whereby it retained the mastery of the waters for a great many years and fought against the practice of piracy successfully.

As a result, it not only remained independent but was also graced with numerous votive gifts, the majority of which could be seen in the Dionysium. The best of them, he believed, was the Colossus of Helios (c. 280 BCE), which, having been brought down by an earthquake and shattered at the knees, then lay in ruin on the land.

Another description comes from the texts of Pliny the Elder. The Roman writer, Pliny the Elder, was also a natural philosopher, military commander, and ally of Emperor Vespasian. Pliny authored the Naturalis Historia, which set a precedent for encyclopedias that followed. The Naturalis Historia is one of the most extensive single publications to have been preserved from the Roman Empire era to the present day, claiming to encompass the entire domain of accumulated knowledge of the ancient world.

According to Pliny, the gigantic Sun statue was by far the most deserving of their respect.

He notes that even though an earthquake knocked down the monument 56 years after it was created, it inspired amazement and respect. Few men could wrap their arms around the thumb, and its fingertips were bigger than most sculptures. Large cavities could be seen gaping in the inside where the limbs had been fragmented. There were also massive amounts of granite visible within it, the mass of which the craftsman used to keep it steady while building it.

Removal of the Fragments of the Colossus of Rhodes

There are various accounts as to what happened to the remainder of the fragments. One account states that an Arabic militia led by Muawiyah I invaded Rhodes, and the remnants of the monument were melted down and traded with an Edessan merchant, who piled the bronze pieces onto around 900 camels. The Arabic dismantling and alleged sale to a foreigner may have been seen as a striking allegory for Nebuchadnezzar’s vision of destroying a huge monument.

Bar Hebraeus tells the same story: “And a large group of men tugged on thick ropes wrapped around the ‘Colossus’ and brought it down. They weighed 3000 tons of brass from it and presented it to a specific trader from Emesa.”

Because of its positioning on the seismically vulnerable Hellenic Arc, Rhodes experiences two major earthquakes every 100 years or so. Pausanias, speaking in the year 174 AD, describes how the town was so damaged by an earthquake that the Sibyl oracle foreshadowing its downfall was deemed fulfilled.

By the 4th century, Rhodes had been Christianized, making any further preservation or reconstruction work of an antique pagan statue improbable.

By the height of the Arabic invasions, the metal would have most likely been utilized for coinage and possibly weapons, especially during subsequent confrontations such as the Sassanian Wars. Furthermore, the island remained a vital Byzantine tactical location far into the 9th century, making an Arabic attack improbable. Theophanes may have been given unclear details about an invasion and blamed the statue’s destruction on it, not understanding much more. Based on these factors, as well as the negative impression of Arabic conquests, some believe the account of the statue’s deconstruction was pure propaganda.

The Colossus Statue in the Modern Era

Large stones discovered on the seabed off the shore of Rhodes in 1989 were first thought to be the remnants of the statue; however, this notion was ultimately dismissed by most researchers. There has been significant discussion about whether or not to construct a reproduction of the Colossus of Rhodes statue.

Those who are in support of the project argue that it would significantly improve tourism in Rhodes, while those opposed argue that it would cost millions of dollars, exceeding US$135 million. Ever since it was initially introduced in 1970, this notion has been revisited several times.

It was made public in November 2008 that the Colossus of Rhodes would be reconstructed. Instead of replicating the historical Colossus, the new structure would be a “very, highly inventive light artwork, one that would rise between 70 and 100 meters into the air so that visitors can actually enter it.”

The initiative is anticipated to cost up to €200 million, with financing coming from foreign contributors and German designer Gert Hof. The new Colossus monument will be shown on an outlying pier in Rhodes’ harbor region, where approaching ships will be able to see it. “Although we are currently in the planning stages,” Koutoulas added, “Gert Hof’s idea is to create the planet’s greatest light artwork, a project that has never previously been seen in any part of the world.”

One of the ancient world’s Seven Wonders, the “Colossus of Rhodes” surely must have been a breathtaking structure to witness in its day. Whether it was located with one foot on either bank of the port entry, or whether it was located on land, based on historical reports, it was an incredibly huge achievement of engineering either way. There is no doubt that it has earned its position on the list of Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Was the Colossus of Rhodes Built?

The Island of Rhodes had always been an area that controlled who could enter the Aegean Sea. It was a region that could be seen as prime territory for invasion by any force who desired to own this tactically perfect location for their own uses. In fact, that is exactly what happened when Poliocretes and his forces tried to invade the island yet were met with stiff opposition for more than a year. Finally admitting defeat, he retreated his forces, satisfied that he had at least gained neutral status from the islanders regarding his other invasions in Egypt. To celebrate their victory, it was decided to construct something in the harbor that they had defended so successfully for more than 12 months.

What Happened to the Colossus of Rhodes?

Although the people of Rhodes had managed to defend themselves against invading forces, the same could not be said in the battle of nature versus the monument itself. Despite having been constructed extremely well, there is very little that gets in the way of a natural disaster like an earthquake, and once it hit the island, the statue tumbled and crumbled under its own weight. Some reports say the remaining pieces fell into the ocean, while others state that fragments lay on the beach for centuries. Many fragments also made their way into the lucrative trade market, where they were bought up by foreign traders and turned into various other items such as coins and weapons for the military.

How Big Was the Colossus of Rhodes?

The monument was said to stand about 32 meters tall. If you wish to think of a modern structure for reference, then simply envision the Statue of Liberty (1876) and you will get a good approximation of the sheer size of the Colossus. Counted among the ancient world’s Seven Wonders, the Colossus of Rhodes was surely a massive structure, having made it on the list due to its enormity, Colossus was a word previously used in reference to any size sculpture, yet has forever (since its construction) been a word used by sculptors to define the size of large-scale works.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, ““Colossus of Rhodes” – The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.” Art in Context. August 24, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/colossus-of-rhodes/

Meyer, I. (2022, 24 August). “Colossus of Rhodes” – The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/colossus-of-rhodes/

Meyer, Isabella. ““Colossus of Rhodes” – The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.” Art in Context, August 24, 2022. https://artincontext.org/colossus-of-rhodes/.