Famous Scary Paintings – Exploring History’s Dark and Creepy Paintings

Famous artworks created throughout history are not only attractive and cerebral but also ageless. Yet, among these magnificent masterpieces are a plethora of dark paintings that reveal humanity’s depravity. These creepy paintings give us insight into the depths of humankind’s suffering and fears.

An Introduction to Scary Artwork

Scary artists have represented the horrific in artworks throughout time, examining topics such as mortality, brutality, and the otherworldly. Throughout history, scary artists utilized their skills to confront subjects of violence and death found in everyday life and conflict. During the European Renaissance, art challenged the rigid, all-powerful Catholic dogma. Scary artwork was used in Medieval Europe to probe the consequences of diseases such as the plague, spanning from the otherworldly to the commonplace. Modern visual art uses horror paintings to tackle difficult societal issues.

Famous Scary / Dark Paintings

The depiction of scriptural themes, full of brutality and impassioned sacrifice, with its manifestation in actual human bodies, established a legacy of horror paintings that continues to the present day. We prepared this unsettling historical collection of major and fascinating dark paintings by sourcing from the enormous oeuvre of creepy paintings created by scary artists throughout history.

Here is our top list of famous scary paintings that deal with the macabre elements of the human experience.

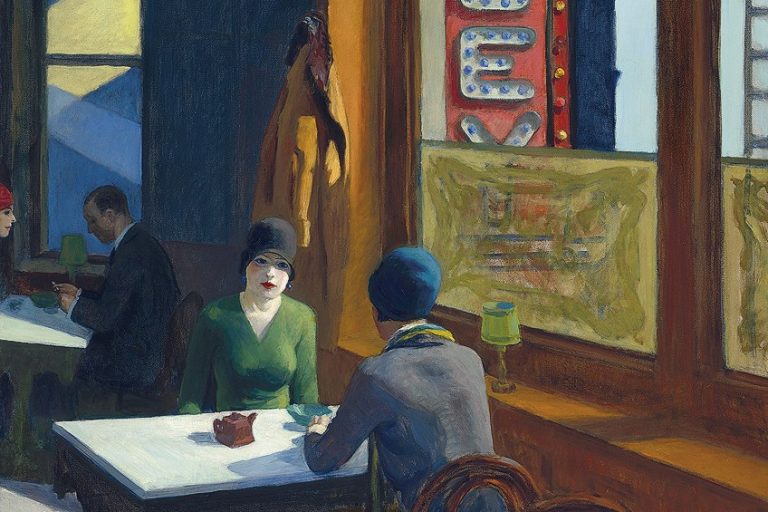

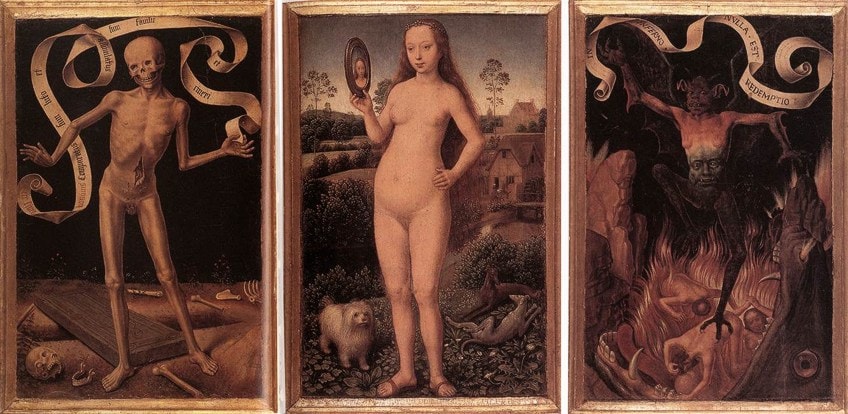

Triptych of Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation (c. 1485) by Hans Memling

| Date Completed | c. 1485 |

| Medium | Oil on Wood |

| Dimensions | 29 cm x 13 cm |

| Currently Housed | Musée des Beaux-Arts of Strasbourg, France |

Hans Memling’s scary artwork juxtaposes ideas of mortality and damnation with the elegance, wealth, and folly of earthly life. The three front panels of this scary painting depict a lovely naked woman staring at her reflection, surrounded along every side by representations of doom and the wicked. Her exposure is intended to be sensual, and it is “really extraordinary for its period.” The significance is enhanced by the inclusion of greyhounds and a small terrier dog, both of which were featured in Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck and are supposed to signify matrimony or, more likely in this case, sexual desire.

The nude’s solely sexual nature is definitely unusual for its period. This is the only instance that the female sexual organs are displayed exposed.

This lady, with a headpiece in her tresses, who stares in the mirror and proudly displays her nakedness save for the footwear, depicts both lust and vanity. The passionate greyhounds on the right are likewise significant. The waterwheel, which is always alluding to the Nativity in Memling and is once again dominant in the environment, might be presented here as a counterpoint to the wicked ways of the body seen in the front. In the Vanity scene, the female’s sexual organs correlate with the frog, the evil monster seen over Death’s sexual organs.

There are no physical indications that suggest whether this panel was initially positioned to the left side of the center panel or the right side.

The Garden of Earthly Delights (1505) by Hieronymus Bosch

| Date Completed | 1505 |

| Medium | Oil Paint |

| Dimensions | 220 cm x 389 cm |

| Currently Housed | Museo Nacional del Prado |

To talk about Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych in the contemporary era is to strive to define the incomprehensible and interpret the indecipherable – an effort in insanity. Nevertheless, there are a few observations that may be stated with confidence. The scary artwork has sometimes been understood as a caution against fleshly and earthly pleasure, yet it seems a somewhat banal aim to a very distinctive and emotively rich visual journey.

In fact, there is little consensus on the work’s specific significance. It is a famous scary painting representing creation and condemnation, beginning with Adam and Eve and concluding with a very creative Hellscape.

Nobody knows for certain why Bosch created the universe in this manner.

The opening panel shows God watching over the presentation of Eve to Adam, appearing like a crazy professor amid a setting enlivened by strangely alchemical flasks and vials. In this context, the presentation of female to male is obviously designed to showcase not just God’s ingenuity but also human reproduction ability. The people, the progeny of Adam and Eve, frolic freely in a hallucinatory picturesque landscape in the second panel, seeming as insane creations of a humorous creator – gears of nature living in a bigger, living mechanism.

It is debatable what the humans are doing in this beautiful, complex, and illogical world, alive with a bewildering assortment of some of Bosch’s most delightful animals and peppered with his alembic buildings.

In the last panel, previous images of Hell, assuming that’s what Bosch envisioned here, pale in contrast to this. Jail cell fortress walls are carved in inky shadows against regions of flames, while human bodies cluster in groups, gather in legions, or are subjected to bizarre cruelties at the claws of strangely dressed executioners and demons.

The Triumph of Death (1562) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

| Date Completed | 1562 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 117 cm x 162 cm |

| Currently Housed | Museo del Prado, Madrid |

The picture depicts a panoramic view of a legion of skeletons spreading devastation across a bleak, charred countryside. Fires rage in the distance, while shipwrecks fill the water. A few leafless shrubs dot otherwise barren slopes, and fish die on the banks of a corpse-filled pond. James Snyder, an art historian, stresses the “charred, desolate land, bereft of any life as much as the eyes can perceive.” In this environment, armies of skeletons approach the living, who either run in horror or fight in futile.

Skeletons pull a wagon full of heads in the forefront, as others strike the world’s death knell in the upper left corner.

People are lured into a cross-decorated coffin-shaped snare, while a skeleton on a horse murders them with a scythe. The picture portrays individuals of many socioeconomic classes – from farmers and warriors to aristocrats, as well as a ruler and a pope – being snatched ruthlessly by death. A skeleton mocks human delight by performing the hurdy-gurdy while his cart’s wheels smash a person like he’s dirt. A lady has fallen into the track of the death cart; she is holding a thin thread that is going to be severed by the shears in her other hand.

The Flaying of Marsyas (1576) by Titian

| Date Completed | 1576 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 212 cm x 207 cm |

| Currently Housed | Archdiocesan Museum Kroměříž |

This scary artwork depicts the skinning alive of a mythic creature who foolishly engaged the god Apollo to a music competition. It is one of the numerous artworks with mythical themes from Ovid that Titian completed in his latter years. Since 1673 The artwork has remained at Moravia and was mostly ignored because it was off the usual path in terms of Venetian artwork. It did not appear in scholarly writings until 1909. It was widely acknowledged as a significant late work among academics by the 1930s, but rarely known to the general public.

Many authors have sought to grasp the message of the “famously violent” work, which has been characterized as the most debated, adored, and despised of all Titian’s works despite the severity of the execution.

One popular theory is that the picture represents concepts from Renaissance Neoplatonism about the “release of the soul from the flesh,” or the attainment of greater understanding or enlightenment. The tale of Marsyas was widely seen as an instance of the unavoidable tragedy that resulted from arrogance in the shape of a dare to a deity. The concept of competition to reinforce the overall moral and aesthetic supremacy of the courtly lyre, or contemporary stringed instruments, over the primitive and whimsical wind instruments was evident in much classical debate and may have held some significance in the 16th century.

Portrait of Antonietta Gonzalez (1595) by Lavinia Fontana

| Date Completed | 1595 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 57 cm x 46 cm |

| Currently Housed | the Musée du Château, Blois |

This specific painting is strange rather than frightening. It appears to be a weird joke perpetrated on an unwary painting model by painter Lavinia Fontana. It is, however, based on a real person. Antonietta Gonzalez and other members of her family have hypertrichosis, often known as “werewolf syndrome,” an uncommon hereditary condition that creates an excessive quantity of hairs on the body. Pedro Gonzalez, Antonietta’s dad, was the first individual to be diagnosed with this disease.

Considering the condition’s scarcity, it’s a little unexpected that numerous members of the Gonzalez clan were impacted by hypertrichosis.

Antonietta and her siblings were invited into European courts after attracting the interest of doctors and aristocrats alike, as well as being subjected to clinical examinations and picture sittings. In the handmade letter she holds in the photograph, Antonietta reveals a little about her personal background: “Don Pietro, a wild man found in the Canary Islands, was transported to the King of France, and then from there proceeded to the Duke of Parma…Who from I, Antonietta, descended, and today I may be seen close at the estate of the noble Marchesa of Soragna.”

Massacre of the Innocents (1611) by Peter Paul Rubens

| Date Completed | 1611 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 142 cm x 182 cm |

| Currently Housed | Art Gallery of Ontario |

This is a common topic in the visual arts, especially during the Renaissance when painters were revisiting history and reinvented mythical and religious themes. The horrifying portrayal of murder ordered by King Herod to thwart the predicted future King of the Jews from inheriting the kingdom was depicted by a number of artists from various periods. In this scary painting, the babies are being slaughtered by naked troops, as their moms are desperately trying to rescue them. The center image is a blood-red-dressed woman who is sliding backward under the burden of an elderly woman who is poised to be wounded by the army.

She’s furiously clawing another trooper’s head with her right hand while clutching the infant with her left.

It’s a fight for preservation, a battle in which human life is at risk. She is pulling the soldier away as he is seen clutching the baby’s robes and almost grabbing the infant. Another horror is going to occur along the top right border of the artwork: a baby hoisted far above by another officer is about to be hurled down on the earth, which is already coated in pallid, lifeless dead.

However, there is some optimism as a little girl, glimpsed by the officer’s left leg, lifts her arms towards the infant, trying to grab him. There is indeed much happening in this scary artwork, yet if one begins with the two groups in the middle as well as the right side: the woman, her kid, and the officer – you will experience the drama of the entire image intensely.

The Nightmare (1781) by Henry Fuseli

| Date Completed | 1781 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 102 cm x 127 cm |

| Currently Housed | Detroit Institute of Art |

This terrifying picture depicts a lady in profound slumber, her arms flung beneath her, and a devilish and animalistic incubus crouching on her breast. The dreamy and disturbing sexual depiction of passion and desire in the artwork was a tremendous commercial triumph. Following its initial exhibition at the Royal Academy of London in 1782, reviewers and supporters responded with terrified curiosity, and the piece became enormously renowned to the point that it was imitated in political comedy and an etched copy was extensively circulated.

In reply, Fuseli created at least three further variations.

The interpretations differ. The painting appears to depict both a dreaming female and the stuff of her nightmares. The incubus and horse’s head are references to modern beliefs and traditions concerning dreams, although some scholars have assigned more precise interpretations to them. Modern reviewers were startled by the artwork’s overt sensuality, which has subsequently been understood by some historians as foreshadowing Jungian concepts about the subconscious.

The Severed Heads (1810) by Théodore Géricault

| Date Completed | 1810 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 65 cm x 76 cm |

| Currently Housed | Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden |

Another well-known artist noted for his creepy paintings is Théodore Géricault. The Severed Heads, a horrific artwork, truly represents humanity in its worst hour. The deterioration of the skulls is obvious. A woman’s head on the left has shut eyelids and a macabre pale complexion, whereas a man’s head on the other side has vacant dead eyes and its mouth partially open. Géricault’s utilization of darker and bright hues to communicate his desire – transition from life to death adds to the composition’s appeal.

Géricault was so preoccupied with death that he was reputed to have genuine severed human remains and corpses in his workspace.

The Severed Heads, like many of Géricault’s previous paintings, allowed him to study depicting the finer features of a body. The stems of the severed heads imply that these previous spirits were beheaded. In fact, though, this is only true for one of them. The man’s guillotined skull was acquired from a criminal previously detained in a clinic that simultaneously functioned as a death-row jail, while the woman’s head was created from a living subject.

As a result, it has been speculated that Géricault’s second motivation for creating this scary painting was to show how both males and females were frequently subjected to guillotine beheading.

Saturn Devouring His Son (1823) by Francisco de Goya

| Date Completed | 1823 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 143 cm x 81 cm |

| Currently Housed | Prado Museum |

This, one of de Goya’s most terrible and dark pictures, is part of the so-called “Black Paintings” series. De Goya produced these paintings directly into the plaster sides of his house on the bank of the Manzanares River near Madrid, which he acquired as a last refuge in 1819. Initially, he adorned the walls with more cheerful themes, but over time, he overpainted them with a series of progressively more horrific and horrific images, most doubt reflecting his growing melancholy and anxiety, as well as concerns about his own impending death. He did not journal about these artworks, nor is it known that he discussed them, nor did he make any attempt to identify them.

Other individuals chose titles for his works years after his demise, depending on the supposed substance and significance of each piece.

Furthermore, the paintings remained undisturbed on the walls for about 50 years before being moved to the canvas in 1874. The image is a masterful depiction of a frantic psychopath stuck in the gloom, unable to stop his violent behavior. Saturn’s raw nakedness, disheveled beard and hair, wide-eyed gaze, and violent gestures all point to frantic insanity. He’s already rippeds` off and devoured his child’s head, right arm, and a portion of his left arm, and he’s going to take another mouthful from the left arm. He’s holding the dead youngster so firmly that his knuckles are pale and blood is oozing from the tops of his hands.

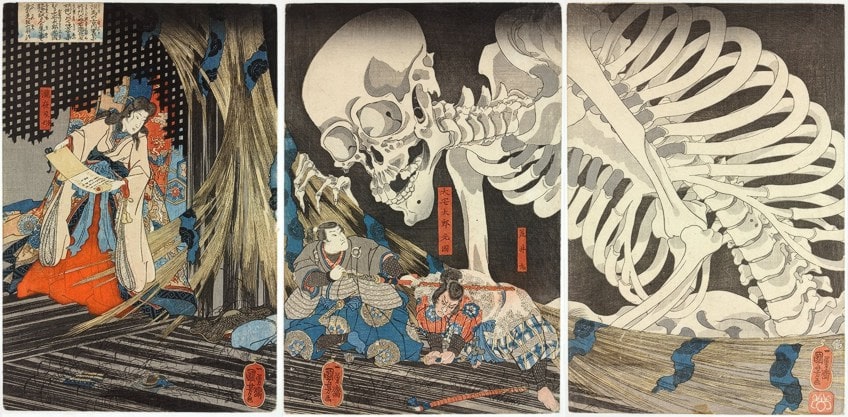

Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Specter (1844) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

| Date Completed | 1844 |

| Medium | Woodblock |

| Dimensions | 35 cm x 71 cm |

| Currently Housed | V & A Museum |

Utagawa Kuniyoshi made the woodblock print Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Specter during the Edo era, in which a gigantic skeleton hovers over two samurai warriors while a lady examines a script in the shadows. The disturbing image is inspired by a tale from Japan’s Heian era, which occurred in 939 CE. During the period, samurai leader Taira no Masakado commanded an attack against the imperial authority in Kyoto from his stronghold in Kant.

He later attempted to establish an “Eastern Court” in Shimosa Province but was overthrown and beheaded.

Princess Takiyasha, his child, remained to reside in the family’s shōen, resorting to sorcery and learning magic spells. Kuniyoshi’s work depicts her casting a ritual to summon a Gashadokuro, a ghost that takes the shape of a gigantic skeleton. It examines Ya Taro Mitsukuni and another warrior who were both dispatched to find the princess. The ghostly spirit thwarted their intentions. It leaps from the darkness, bursting through the torn palace shutters with its skeletal fingers to threaten Mitsukuni and his friend.

Dante and Virgil (1850) by William-Adolphe Bouguereau

| Date Completed | 1850 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 281 cm 225 cm |

| Currently Housed | Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

Dante and Virgil may not appear to be very scary artwork at first glance, but when coupled with its narrative, it transforms into a horrific visual encounter. The painting depicts an episode from Dante’s Divine Comedy. Dante and his companion, Virgil, have gone into Hell and have come to a halt at the Eighth Circle. This area of Hell is designated for those who have defrauded mankind.

Dante and Virgil testify to two condemned souls involved in an endless battle to the death. Capoccia, both a chemist and rebel, is on the one side, and Gianni Schicchi, who is a prankster and scammer, is on the other.

Aside from the horrific setting of monsters, a furnace, and nude humans moaning in pain, the most striking aspect of this painting is the exquisite portrayal of the combatants’ bodies.

Bouguereau has portrayed the “heat of the moment” well, highlighting Schicchi’s ferocious power, the elegance of the men’s stances, and the sheer despair in their emotions. Ultimately, this scary painting serves as an aesthetic aide-mémoire, emphasizing how people are all equals in God’s eyes, and how being exiled to Hell transforms one into neither man nor monster, but somewhere in between the two.

Bouguereau was not one of the usual scary artists and the painting was the first and last of his works to explore this topic, implying that the gloomy content was probably too upsetting for him to replicate.

Aurora Triumphans (1876) by Evelyn de Morgan

| Date Completed | 1876 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 120 cm x 170 cm |

| Currently Housed | Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum |

Aurora, the Roman goddess of the morning, leans back at the bottom right, the chains of the darkness shown as knotted flowers. Darkness is floating away in her black garments in the bottom left-hand corner. Three winged spirits dazzling in their golden robes strike the trumpets ushering in the day above them. Aurora triumphantly vanquishes Night. The two main characters in this basic tale are positioned in static positions, as though in a tableau, as was customary in Pre-Raphaelite narrative art.

With the inclusion of the angels, which command the picture and nearly contribute sound, De Morgan changes the usual composition.

This scary painting has an intriguing backstory as well. It was first shown at the Grosvenor Gallery in London and then appears to have been in a private collection until it was put on the market about 1922. De Morgan’s name had been retouched with Burne-Jones’ at the time. On that basis, it was acquired for the Russell-Cotes Museum in Bournemouth, where it is currently shown as one of de Morgan’s artworks. De Morgan, a Spiritualist and hence a fervent devotee in the hereafter, created this depiction of the Angel of Death gathering spirits to carry to the other side.

Pyramid of Skulls (1901) by Paul Cézanne

| Date Completed | 1901 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 37 cm x 45 cm |

| Currently Housed | Private Collection |

Pyramid of Skulls is an artwork of four human skulls piled in a pyramidal pattern. This scary artwork painted in a faint light on a black backdrop is unique in the artist’s work because “in no other picture did the artist place his elements so near to the observer.” Cézanne repeatedly referred to dying in his letters while working in seclusion in the last decade of his life: “Life has become deathly dull for me”; “As for myself, I’m elderly. I won’t be able to convey myself”; and “I would as well be gone.”

It’s conceivable that his mother’s death on the 25th of October, 1897 – she had been a caring and supporting figure – hastened his contemplations on death, a theme that had tormented the painter since the late 1870s but would not find an artistic shape for yet another 20 years.

At the very same time, Cézanne’s condition began to worsen. The emotional acceptance of death inspires a series of horror paintings he created between 1898 and 1905. These dark paintings, some in watercolors and some in oils, are more nuanced in content while also being more aesthetically striking than the usual approach to the topic of vanitas. Pyramid of Skulls was completed at Cézanne’s Aix studio ahead of his departure to the newer Les Lauves workshop in 1902.

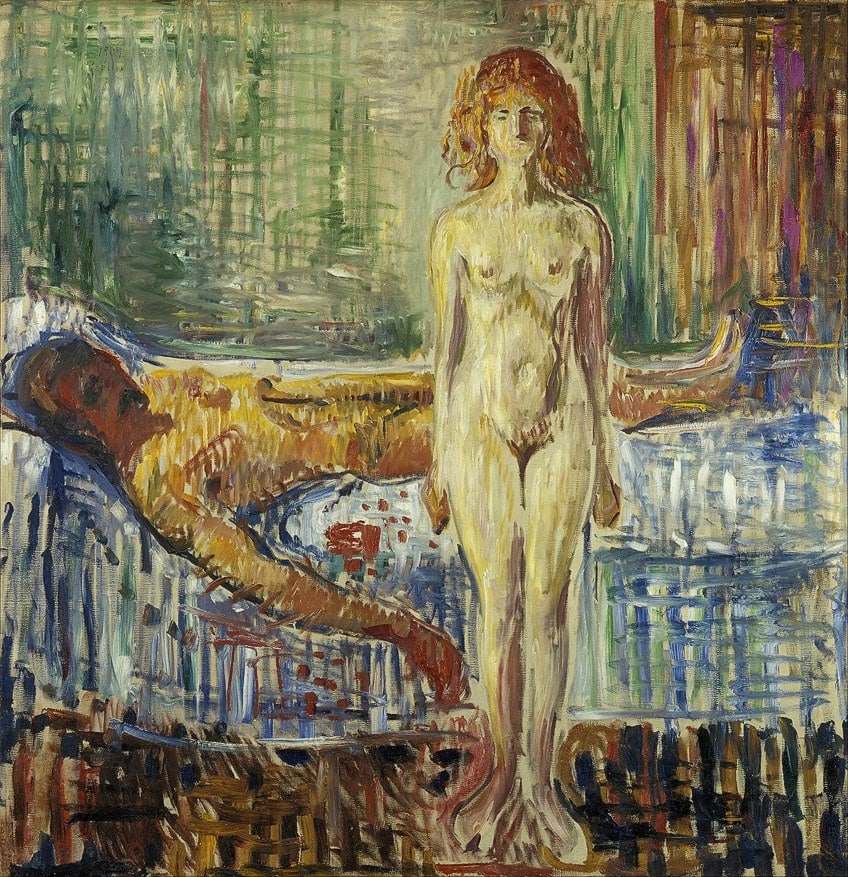

The Death of Marat II (1907) by Edvard Munch

| Date Completed | 1907 |

| Medium | Oil o Canvas |

| Dimensions | 150 cm x 200 cm |

| Currently Housed | Old masters Museum |

This next terrifying picture is inspired by the melancholy of life experiences, especially whenever it relates to the end of a romance. The Death of Marat II was created by the great Norwegian artist Edvard Munch and has one awful tale behind it—actually, two. It all began in 1902 when Munch ended things with his girlfriend, Tulla Larsen. According to reports, the couple argued at his vacation home in Aasgaardstrand, and during the scuffle, a pistol went off, injuring Munch’s wrist. This tragedy disturbed the painter, who implied that Larsen was to blame, and inspired two paintings: The Death of Marat and this follow-up painting.

The topic of both titles, “Marat,” relates to a French rebel murdered in a bath in 1793 by extremist Charlotte Corday.

Rather than Marat and Corday, the subject of this scary painting is believed to be Munch laying lifeless on the mattress, with a nude Larsen standing erect next to him. The gash on the person’s arm – representing Munch wounding his own hand amid his earlier argument with Larsen—and the physical resemblance between the lady in the picture and Larsen herself are the major reasons why she is regarded as his murderer. Munch created the picture while experimenting with expressionistic methods.

He created a distinct technique: unique lateral and vertical brushwork that reflected his aggressiveness and unsettled mental condition, which finally led to his collapse in 1908.

The Face of War (1940) by Salvador Dalí

| Date Completed | 1940 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 64 cm x 79 cm |

| Currently Housed | Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen |

This work was completed in California at the end of 1940; the horrifying face of battle, its eyes brimming with limitless murder, was reminiscent of the Civil War of Spain rather than World War II, which had not yet supplied a procession of horrific pictures sufficient of stunning Dalí at the moment. The scary painting’s terror is heightened by the brown tonalities that dominate its mood.

On the artistic side, Dalí has stated that it was the only piece in which the genuine impression of his fingers on the painting could be seen (at the bottom right).

“The two greatest energetic actuators that make my artistic brain function are, firstly, sex drive, or the sexual impulse, and, second, the distress of dying. Not a single second of my life goes by without the exquisite Religious, episcopal, and Roman apparition of death escorting me even in the least significant of my most nuanced and arbitrary imaginings,” Dali wrote in his diary.

The deeper you look at the terrifying artwork, the more horrifying yet painfully on-point elements emerge. The picture depicts a disembodied head on a desert landscape, with a gaunt face like a cadaver, being attacked by snakes. Its appearance is dismal and abandoned, as Dal intended: to depict the horror of battle. Within the lips and eye sockets are similar heads, and within them are additional duplicate heads, making this feature endless, a dismal notion.

And that brings to a close our list of famous scary paintings. Scary artists have made horror paintings through the centuries that reflect the darker side of man. These creepy paintings still produce unease and fear in those who observe them.

Take a look at our creepy paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Did Artists Create Creepy Paintings?

Scary artists created creepy paintings for many reasons. Sometimes it was to reflect the state of the world they lived in, either politically or religiously. Other times it was to reflect their own inner fears.

Are Dark Paintings Evil?

Although the subject matter might sometimes cover evil and demons, usually the story originates from a myth or scripture. Artists might choose to produce a piece to portray a specific spiritual lesson. Other times it could be a symbolic representation of something else completely.

Emma completed her Bachelor’s Degree in International Studies at the University of Stellenbosch. She majored in French, Political Science, and History. She graduated cum laude with a Postgraduate Diploma in Intercultural Communication. However, with all of these diverse interests, she became confused about what occupation to pursue. While exploring career options Emma interned at a nonprofit organization as a social media manager and content creator. This confirmed what she had always known deep down, that writing was her true passion.

Growing up, Emma was exposed to the world of art at an early age thanks to her artist father. As she grew older her interests in art and history collided and she spent hours pouring over artists’ biographies and books about art movements. Primitivism, Art Nouveau, and Surrealism are some of her favorite art movements. By joining the Art in Context team, she has set foot on a career path that has allowed her to explore all of her interests in a creative and dynamic way.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Emma, Littleton, “Famous Scary Paintings – Exploring History’s Dark and Creepy Paintings.” Art in Context. October 29, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-scary-paintings/

Littleton, E. (2021, 29 October). Famous Scary Paintings – Exploring History’s Dark and Creepy Paintings. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-scary-paintings/

Littleton, Emma. “Famous Scary Paintings – Exploring History’s Dark and Creepy Paintings.” Art in Context, October 29, 2021. https://artincontext.org/famous-scary-paintings/.