Cinemascope – The Allure of Panoramic Film

Cinemascope, often referred to as “widescreen” or “scope,” is a cinematic canvas that transcends the boundaries of conventional filmmaking, ushering audiences into a realm of visual splendor and storytelling grandeur. This monumental innovation in the world of cinema is nothing short of a transformative force, allowing filmmakers to paint their narratives on a broader and more immersive canvas. With its breathtaking aspect ratio, Cinemascope weaves a tapestry of panoramic vistas and intimate close-ups, engaging our senses in a profound and enveloping cinematic experience. From the grand epics of yesteryears to the contemporary blockbusters, Cinemascope is a powerful tool that has forever altered the way we perceive and engage with the magic of the silver screen.

What Is Cinemascope?

Cinemascope, a term that evokes visions of cinematic grandeur and breathtaking vistas, is a technical marvel in the world of filmmaking. It represents a pivotal moment in the history of cinema, one where technology and artistry converge to redefine the way we experience the magic of cinema.

To truly appreciate Cinemascope, it is essential to delve into the technical intricacies that underpin this cinematic format, as it is not merely an aspect ratio but a complex interplay of optics, cameras, and projection systems.

The Anamorphic Lens

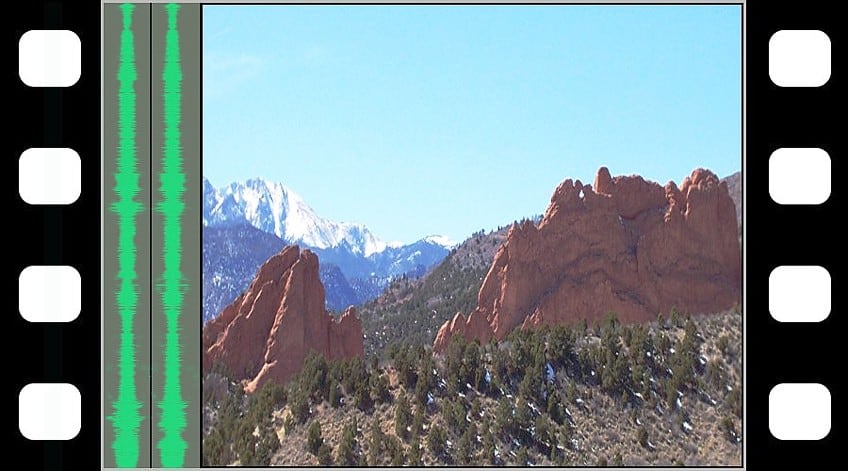

At the heart of Cinemascope’s technical innovation lies the anamorphic lens, a marvel of optical engineering that stretched the boundaries of conventional filmmaking. Henri Chrétien, the French inventor responsible for this groundbreaking technology, introduced a novel concept: the ability to squeeze a wider field of view onto standard 35mm film, only to have it later expanded during projection. This process is what defines anamorphic photography, and it is the very soul of Cinemascope. The anamorphic lens is often referred to as the “Cinemascope lens.” Its unique design allows for the horizontal compression of the image during filming, effectively “squeezing” it onto the film negative. This compression is a key component of Cinemascope’s distinctive widescreen aspect ratio, which typically hovers around 2.35:1.

It is a wide frame that gives Cinemascope its characteristic panoramic view, immersing audiences in a world that feels larger than life.

One of the remarkable features of the anamorphic lens is its ability to create the elongated oval “bokeh” or out-of-focus areas in the background of the image. This optical characteristic, often described as the “Cinemascope look,” is instantly recognizable and deeply associated with the format. It adds a touch of artistry to the technical brilliance, emphasizing the fusion of technology and aesthetics that is a hallmark of Cinemascope.

The Expanded Horizons of Cinemascope

The format’s strengths extend beyond mere aspect ratio, however. Cinemascope encourages filmmakers to explore new creative horizons, making every shot a canvas for artistic expression. The expanded frame allows for intricate and dynamic shot compositions, as the full expanse of the screen becomes a medium for conveying meaning and emotion. Cinematographers can play with foreground and background elements in ways that were previously unattainable, adding depth and complexity to the visual narrative.

Accompanying the visual spectacle of Cinemascope, many theaters also featured a multi-channel sound system, further enhancing the immersive experience for audiences.

The combination of expansive visuals and rich, multidimensional sound elevated the movie-watching experience to a multisensory journey. This technical synergy between visual and auditory elements transformed cinema into a truly immersive art form.

Cinemascope’s technical innovation was a response to the challenge faced by the film industry in the 1950s, primarily the competition posed by the burgeoning television industry. As more households acquired television, the allure of the silver screen began to wane. Hollywood needed a compelling reason for audiences to return to theaters, and Cinemascope provided just that. Its introduction with The Robe in 1953 marked a turning point in cinematic history. Audiences were captivated by the expanded visuals, and the widescreen revolution had begun.

Cinemascope’s Positive Effect on Films

In addition to its role in revitalizing the film industry, cinemascope provided filmmakers with a tool to create cinematic spectacles that were hitherto unimaginable. It was tailor-made for epic storytelling, capturing vast landscapes and grand battles with a groundbreaking realism that left audiences in awe. Films like Ben-Hur (1959) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962) leveraged the format’s capabilities to transport viewers to distant worlds and immerse them in the grandeur of cinematic storytelling. Yet, Cinemascope’s impact extended far beyond the realm of epic blockbusters. It was a versatile format that could be applied to intimate storytelling with equal finesse. Directors like Alfred Hitchcock employed Cinemascope to create tension and suspense in films like Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958).

The format’s ability to emphasize both panoramic vistas and intimate close-ups made it a valuable tool for a wide range of narratives.

Cinemascope’s success was not limited to the United States, it quickly gained popularity worldwide, inspiring filmmakers in various countries to harness its potential. The format’s ability to transcend language and cultural barriers further cemented its status as a global cinematic icon. In the decades that followed, Cinemascope continued to evolve technologically. Different anamorphic processes were developed, each with its own variations and improvements, further expanding the possibilities of widescreen cinema. These advancements ensured that Cinemascope remained a vibrant and dynamic format, ever-relevant in the ever-changing landscape of filmmaking.

Cinemascope’s legacy is evident in the continued use of widescreen formats in contemporary cinema. Filmmakers still draw upon the lessons of Cinemascope to create visually compelling narratives that engage and captivate audiences. The format’s spirit lives on in the quest for cinematic innovation, driving the industry to provide audiences with a more immersive and breathtaking experience. The influence of Cinemascope goes beyond the realm of cinema. It has inspired the world of photography, with photographers adopting anamorphic lenses to capture wide, cinematic vistas with the same sense of grandeur and awe. The idea of widescreen storytelling has transcended film and found applications in various visual mediums, from advertising to music videos, enriching our visual culture.

The Origin of Cinemascope

Cinemascope, a name that resonates with the magic and grandeur of the silver screen, was not merely a cinematic innovation; it was a groundbreaking revolution that forever altered the landscapes of filmmaking. Its origin story is a testament to the ingenuity of individuals who, in the face of mounting challenges, reshaped the world of cinema.

The birth of Cinemascope is a tale of technical brilliance, visionary inventors, and the ever-evolving quest to provide audiences with a truly immersive cinematic experience.

In the early 1950s, Hollywood found itself at a crossroads. The golden age of cinema was facing a formidable adversary in the form of television. As more American households acquired television sets, the allure of the silver screen began to fade, and movie attendance plummeted. Hollywood needed a compelling reason for audiences to return to the grandeur of theaters, and the solution lay in a radical reimagining of the cinematic experience.

The Invention of Cinemascope

The crucial moment arrived in 1953 when 20th Century Fox unveiled Cinemascope to the world. It was a cinematic format designed to be the antidote to the encroaching dominance of television. Cinemascope, with its striking widescreen visuals, was born out of a quest to provide audiences with something they could not find on their small black-and-white TV screens. The key figure behind this transformation was not a Hollywood mogul, but a French inventor named Henri Chrétien. Chrétien’s groundbreaking invention, the anamorphic lens, is at the heart of Cinemascope’s origin. This lens allowed for the horizontal stretching and squeezing of images, effectively fitting a wider aspect ratio onto 35mm film.

The compressed image would then be expanded during projection, unveiling the spectacular widescreen format that became synonymous with Cinemascope.

The anamorphic lens, often referred to as the “Cinemascope lens,” is the linchpin of this transformation. Its unique design allowed filmmakers to squeeze more visual information onto the film negative, thereby creating the wide, panoramic aspect ratio that defines Cinemascope, typically around 2.35:1. This widening of the frame gave Cinemascope its characteristic visual grandeur, immersing audiences in a world that felt larger than life.

One of the most distinctive features of the anamorphic lens is its ability to create the elongated oval bokeh effect. This optical characteristic, often described as the “Cinemascope look,” is instantly recognizable and adds an artistic touch to the technical brilliance. It is this unique visual signature that has made Cinemascope an enduring icon in the world of cinema.

Cinemascope’s Introduction to the Film Industry

The introduction of Cinemascope with the film The Robe in 1953, directed by Henry Koster, marked a watershed moment in cinematic history. Audiences were captivated by the expansive visuals and the newfound sense of immersion in film. The success of The Robe paved the way for the widescreen revolution in cinema, as other studios and filmmakers eagerly adopted the Cinemascope format. Cinemascope’s impact extended beyond the borders of the United States, quickly becoming a global phenomenon. Filmmakers around the world embraced the format, recognizing its potential to captivate and engage audiences. Cinemascope was not confined by language or cultural barriers; it was a universal language of cinematic storytelling.

The format’s technical brilliance was not limited to its unique aspect ratio.

Cinemascope encouraged filmmakers to explore new creative horizons, making every shot a canvas for artistic expression. The expanded frame allowed for intricate and dynamic shot compositions, as the full expanse of the screen became a medium for conveying meaning and emotion. Cinematographers could play with foreground and background elements in ways that were previously impossible, adding depth and complexity to the visual narrative.

Moreover, Cinemascope films were often presented in theaters with a multi-channel sound system, further enhancing the immersive experience for audiences. The combination of expansive visuals and rich, multidimensional sound elevated the movie-watching experience to a multisensory journey, rekindling the magic of cinema and enticing audiences back to theaters. Cinemascope’s success was not confined to the realm of narrative storytelling; it also influenced the world of advertising and promotional films.

Advertisers recognized the format’s capacity to captivate and engage viewers, and Cinemascope quickly became a popular choice for commercials and promotional materials.

The Legacy of Cinemascope

The legacy of Cinemascope continues to shape the cinematic landscape to this day. While the format itself has evolved over the years, its impact is still evident in contemporary filmmaking. Filmmakers continue to draw upon the lessons of Cinemascope to create visually compelling narratives that engage and captivate audiences. Cinemascope’s spirit lives on not only in widescreen formats but also in the ongoing quest for cinematic innovation. The desire to provide audiences with a more immersive and breathtaking experience remains a driving force in the industry.

The use of IMAX and other large-format screens is a testament to the enduring appeal of larger-than-life visuals and sound. Moreover, the anamorphic lens, originally developed for Cinemascope, has found applications in various visual mediums beyond traditional cinema. It has been embraced by the world of photography, enabling photographers to capture wide, cinematic vistas with the same sense of grandeur and awe.

Cinemascope’s First Few Films

The birth of Cinemascope in the early 1950s marked a turning point in the history of cinema. This widescreen format, born out of innovation and the need to reinvigorate the film industry, made its debut with a handful of remarkable films that not only captivated audiences but also forever transformed the way we experience movies.

These first few Cinemascope films were pioneers, leading the way for the widescreen revolution and leaving an indelible mark on the world of cinematic storytelling.

Henry Koster’s The Robe (1953)

| Film Name | The Robe |

| Director | Henry Koster |

| Year of Release | 1953 |

| Main Cast | Richard Burton, Jean Simmons, and Victor Mature |

The Robe, directed by Henry Koster and released in 1953, holds the distinction of being the very first film to be presented in the Cinemascope format. As the inaugural Cinemascope film, it not only set the stage for the widescreen revolution but also marked the beginning of a new era in cinematic storytelling. This biblical epic, based on a novel by Lloyd C. Douglas, was a stunning showcase of Cinemascope’s capabilities. Audiences were immediately captivated by the expansive visuals and immersive experience that Cinemascope offered.

The film’s grandeur and spectacle were enhanced by the widescreen format, allowing viewers to be transported to ancient Rome and witness the dramatic journey of the film’s protagonist, a Roman tribune, who comes into possession of the robe of Jesus Christ. The Robe was a resounding success, not only at the box office but also in showcasing the potential of Cinemascope. The widescreen format brought the grandeur of ancient Rome to life with its panoramic vistas and rich, multidimensional sound. It set a new standard for epic filmmaking and left an indelible mark on the history of cinema.

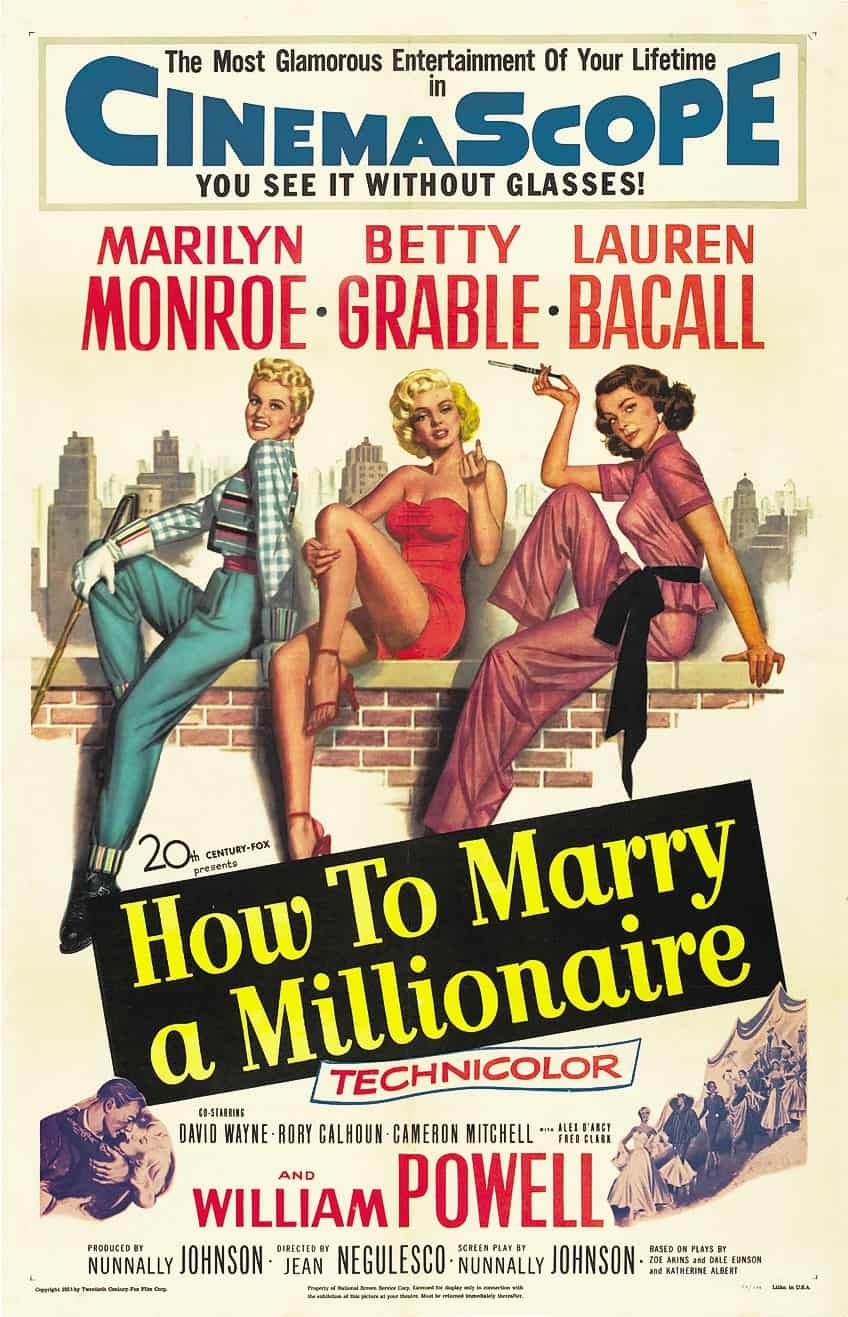

Jean Negulesco’s How to Marry a Millionaire (1953)

| Film Name | How to Marry a Millionaire |

| Director | Jean Negulesco |

| Year of Release | 1953 |

| Main Cast | Marylin Monroe, Betty Grable, and Lauren Bacall |

In the same year, 1953, Cinemascope continued to make its presence felt with the romantic comedy How to Marry a Millionaire. Directed by Jean Negulesco and starring screen legends Marylin Monroe, Betty Grable, and Lauren Bacall, the film was a departure from the epic scale of The Robe, but was no less impactful in showcasing the versatility of Cinemascope. This charming comedy proved that Cinemascope was not confined to grand epics but could also serve as a powerful tool for intimate storytelling.

The format’s wide frame was used to great effect, providing room for the three leading ladies to shine and for their comedic antics to take center stage.

The film’s sequences, from Monroe’s nearsighted character trying to navigate a dinner party to Grable’s character trying to make a successful landing in a plane, were all enhanced by the format. How to Marry a Millionaire demonstrated that Cinemascope was not limited by genre; it was a versatile format that could enrich a wide range of narratives. Its success in a romantic comedy setting paved the way for Cinemascope’s enduring influence in various film genres, proving that it could enhance the visual storytelling of diverse stories.

Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955)

| Film Name | The Seven Year Itch |

| Director | Billy Wilder |

| Year of Release | 1955 |

| Main Cast | Marilyn Monroe, Tom Ewell, and Evelyn Keyes |

Two years after the introduction of Cinemascope, one of the most iconic and memorable films in the history of cinema made its mark in the format. The Seven Year Itch, directed by Billy Wilder and starring Marylin Monroe, became a classic of its era, and its influence on popular culture endures to this day. The film’s use of Cinemascope was not just a technical choice but an integral part of its storytelling. The wider frame allowed for the visual juxtaposition of the cramped New York City apartment where the main character’s desire for freedom and adventure.

The famous scene of Marylin Monroe’s white dress billowing up as she stands over a subway grate became an iconic moment in cinematic history, thanks in part to the format’s ability to capture the scene in all its visual splendor. The Seven Year Itch highlighted Cinemascope’s ability to emphasize both panoramic vistas and intimate close-ups, adding depth and meaning to the narrative. This film showcased how Cinemascope could enhance the visual storytelling of a character-driven story and make a lasting impact on the collective imagination.

Fred Zinnemann’s Oklahoma! (1955)

| Film Name | Oklahoma! |

| Director | Fred Zinnemann |

| Year of Release | 1955 |

| Main Cast | Gordon MacRae, Gloria Grahame, and Gene Nelson |

One of the most beloved and enduring musicals in the history of cinema, Oklahoma! also made its mark in Cinemascope in 1955. Directed by Fred Zinnemann and based on the famous stage musical by Rodgers and Hammerstein, the film utilized the widescreen format to transport audiences to the sweeping landscapes and vibrant community of Oklahoma Territory at the turn of the 20th century. The use of Cinemascope in Oklahoma! was a testament to the format’s ability to capture the expanse and energy of a musical on a grand scale.

The film’s iconic opening sequence, featuring Gordon MacRae singing Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’ against the backdrop of a vast, sun-drenched prairie, was a visual and auditory spectacle that left a profound impression on audiences. The film’s musical numbers, choreographed to make the most of the widescreen format, created a sense of grandeur and immersion that is synonymous with the best of Hollywood’s golden age. Oklahoma! demonstrated that Cinemascope was not only a tool for visual storytelling but also a means to elevate the musical genre to new heights of cinematic artistry.

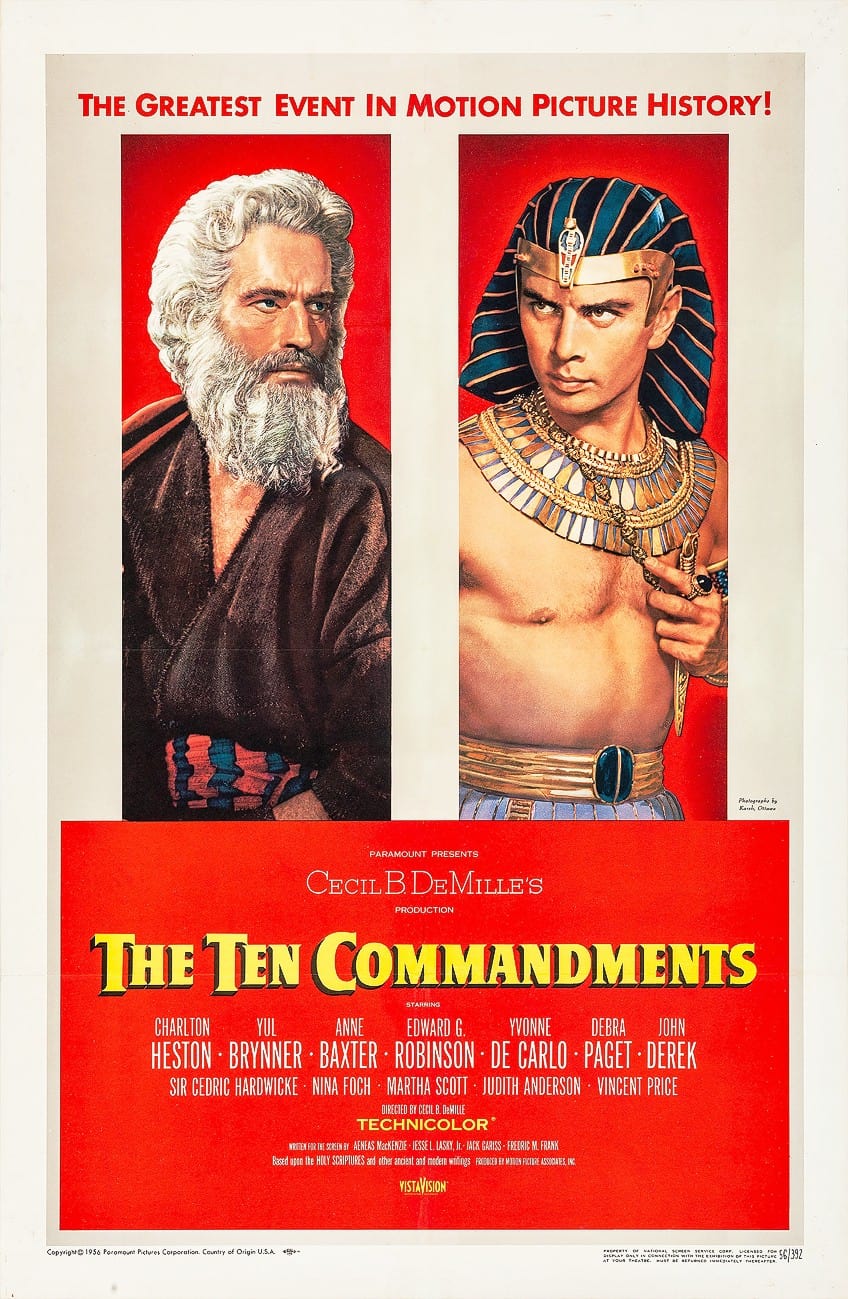

Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956)

| Film Name | The Ten Commandments |

| Director | Cecil B. DeMille |

| Year of Release | 1956 |

| Main Cast | Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner, and Anne Baxter |

Cinemascope’s reign in the film industry continued with Cecil B. DeMille’s epic masterpiece, The Ten Commandments, released in 1956. This biblical epic was a monumental production that utilized the widescreen format to its full potential, capturing the grandeur and spectacle of ancient Egypt and the exodus of the Israelites in stunning detail. The Ten Commandments remains one of the most iconic and enduring films in cinematic history, and its impact on the use of Cinemascope in epic storytelling cannot be overstated. The widescreen format allowed for the depiction of vast desert landscapes, elaborate sets, and epic battle scenes on an unprecedented scale.

Cinemascope’s widescreen frame accentuated the film’s sense of grandeur and made the biblical events come to life in a way that was previously unimaginable.

The film’s parting of the Red Sea sequence, achieved through groundbreaking special effects, remains one of the most awe-inspiring moments in cinematic history and is synonymous with the visual spectacle made possible by cinemascope.

The first few films of Cinemascope’s era were pioneers that showcased the format’s versatility and its ability to enrich a wide range of narratives. From epic biblical tales to romantic comedies and iconic musicals, these films left an indelible mark on the world of cinema, demonstrating that Cinemascope was more than just a technical innovation – it was a tool for elevating the art of storytelling.

The Pros and Cons of Cinemascope

Cinemascope, with its expansive widescreen format, has had a profound impact on the world of filmmaking, offering a canvas for filmmakers to create visually stunning and immersive experiences. However, like any technology, it comes with its own set of pros and cons. Let us explore the advantages and disadvantages of Cinemascope, a format that has left an indelible mark on the history of cinema.

The Pros of Cinemascope

From providing audiences with an immersive visual experience to enabling dynamic shot compositions and versatile storytelling, the pros of Cinemascope are a testament to its power to captivate and engage viewers on a grand scale.

Let us explore these advantages in more detail.

Immersive Visual Experience

The most evident advantage of Cinemascope is its ability to provide audiences with a more immersive visual experience. The widescreen format allows filmmakers to capture vast landscapes, epic battles, and intricate set designs in a way that draws viewers into the world of the film. This immersion creates a profound connection between the audience and the narrative.

Dynamic Shot Compositions

Cinemascope encourages dynamic shot compositions, utilizing the full width of the screen to convey emotions and narrative depth. The expanded frame enables filmmakers to play with foreground and background elements, adding depth and complexity to the visual storytelling.

This results in visually captivating and artistically rich films.

Versatility

Cinemascope is a versatile format that can accommodate a wide range of narratives. While it is often associated with epic spectacles, it has been successfully used in various genres, including romantic comedies, musicals, and intimate character-driven stories. This versatility has allowed filmmakers to experiment with different visual storytelling techniques.

Cinematic Spectacle

Cinemascope is synonymous with cinematic spectacle. Films shot in this format often feature grand and awe-inspiring sequences that leave a lasting impact on audiences. The widescreen frame enhances the scale and grandeur of epic storytelling, making it ideal for historical dramas and adventure films.

Timeless Aesthetic

The distinctive “Cinemascope look,” with its elongated oval bokeh and widescreen aspect ratio, has a timeless and iconic quality. This aesthetic has become a hallmark of cinematic artistry, ensuring that films shot in Cinemascope continue to captivate audiences for generations to come.

Innovative Sound Systems

Many theaters equipped for Cinemascope presentations feature multi-channel sound systems that complement the expansive visuals. This synergy of visuals and sound elevates the movie-watching experience, making it a multisensory journey that engages all the senses.

The Cons of Cinemascope

While the formats immersive qualities and cinematic spectacle are undeniable, it is essential to acknowledge and address these drawbacks to make informed decisions when employing Cinemascope in the storytelling process. In this section, we will delve into the cons of Cinemascope, highlighting the aspects that filmmakers need to navigate to fully harness the format’s potential.

Production Challenges

Filming in Cinemascope can present significant production challenges. The widescreen format requires special anamorphic lenses and modified camera equipment, which can be bulkier and more complex to operate.

This can lead to increased production costs and technical challenges for filmmakers.

Limited Accessibility

Not all theaters are equipped to screen Cinemascope films properly. The need for specialized projection equipment and screens with the appropriate aspect ratio can limit the accessibility of Cinemascope films for audiences. This can result in a fragmented viewing experience, with some viewers missing out on the intended visual impact.

Visual Distortion

The anamorphic lens system, which is at the heart of Cinemascope, can sometimes introduce optical distortions, such as barrel distortion and anamorphic flare. While these distortions can add a unique visual quality, they may not be suitable for all types of storytelling.

In addition, filmmakers must carefully manage these effects.

Intimate Storytelling Challenges

While Cinemascope is versatile, it may pose challenges for filmmakers aiming to create intimate storytelling experiences. The wide frame can sometimes distance the audience from the characters and their emotions, making it less suitable for certain types of character-driven narratives.

Aspect Ratio Constraints

Cinemascope’s fixed aspect ratio, typically around 2.35:1, can limit the visual options available to filmmakers. While this aspect ratio is ideal for many scenarios available to filmmakers. While this aspect ratio is ideal for many scenarios, it may not be the best fit for every film.

Some directors may find it restrictive when trying to achieve specific visual effects or storytelling objectives.

Audience Engagement

While the immersive nature of Cinemascope can be a significant advantage, it can also pose challenges in terms of audience engagement. Some viewers may find the widescreen format overwhelming or distracting, potentially detracting from their overall enjoyment of the film. Cinemascope, with its widescreen format and iconic visual style, has been a powerful tool for filmmakers, offering both opportunities and challenges. Its immersive visual experience, dynamic shot compositions, versatility, and ability to create cinematic spectacles have made it a beloved format in the world of cinema. However, the production challenges, limited accessibility, potential visual distortions, and constraints of the fixed aspect ratio must also be considered.

Ultimately, the decision to use Cinemascope should be driven by the filmmaker’s artistic vision and the specific needs of the story. When used thoughtfully and creatively, Cinemascope can elevate cinematic storytelling to new heights, leaving an enduring mark on the history of film. Its pros and cons are not merely technical considerations but elements that contribute to the rich and diverse tapestry of cinematic artistry.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Cinemascope?

Cinemascope, also known as anamorphic widescreen, is a cinematic format that utilizes anamorphic lenses to capture a wider field of view on standard 35mm film. This format is characterized by its distinctive widescreen aspect ratio, typically around 2.35:1, which provides a panoramic view, making the cinematic experience more immersive and visually striking.

Why Was Cinemascope Developed?

Cinemascope was developed in response to the rising popularity of television in the early 1950s, which posed significant challenges to the film industry. Hollywood needed a compelling reason for audiences to return to theaters, and Cinemascope’s widescreen format provided that novelty and immersion.

How Does Cinemascope Enhance the Visual Storytelling of a Film?

Cinemascope enhances visual storytelling by offering a wider canvas for filmmakers to work with. The expanded frame allows for dynamic shot compositions, emphasizing both panoramic vistas and intimate close-ups. This capability adds depth and complexity to the narrative, making it visually captivating and artistically rich.

Duncan completed his diploma in Film and TV production at CityVarsity in 2018. After graduation, he continued to delve into the world of filmmaking and developed a strong interest in writing. Since completing his studies, he has worked as a freelance videographer, filming a diverse range of content including music videos, fashion shoots, short films, advertisements, and weddings. Along the way, he has received several awards from film festivals, both locally and internationally. Despite his success in filmmaking, Duncan still finds peace and clarity in writing articles during his breaks between filming projects.

Duncan has worked as a content writer and video editor for artincontext.org since 2020. He writes blog posts in the fields of photography and videography and edits videos for our Art in Context YouTube channel. He has extensive knowledge of videography and photography due to his videography/film studies and extensive experience cutting and editing videos, as well as his professional work as a filmmaker.

Learn more about Duncan van der Merwe and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Duncan, van der Merwe, “Cinemascope – The Allure of Panoramic Film.” Art in Context. November 23, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/cinemascope/

van der Merwe, D. (2023, 23 November). Cinemascope – The Allure of Panoramic Film. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/cinemascope/

van der Merwe, Duncan. “Cinemascope – The Allure of Panoramic Film.” Art in Context, November 23, 2023. https://artincontext.org/cinemascope/.