What Was the First Movie in Color? – A Technicolor Triumph

The world of cinema has been a canvas of innovation since its inception, with each breakthrough pushing the boundaries of storytelling and visual artistry. One such milestone in cinematic history revolves around the fervent quest for color. Many cinephiles often ponder, “What was the first movie in color?”, contemplating what marked the debut of color in film over questions like “was The Wizard of Oz the first color movie?”. The journey towards full-color motion pictures was a gradual one, and the first color movie was a product of relentless experimentation. In this exploration, we will traverse the fascinating evolution of when movies were made in color, and how this transformative shift forever altered the landscape of cinema.

When Were Movies Made in Color?

Cinema has undergone a series of transformative revolutions, and one of the most striking among them is the transition from black and white to color. The journey of filming the original color movies is a captivating tale of innovation, experimentation, and the relentless pursuit of realism. While we now take color films for granted, the process of bringing color to the silver screen was a complex and fascinating evolution that spanned decades.

Our deep dive below, we will delve into the history of color in film, from its earliest beginnings to the breakthrough moments that forever altered the cinematic landscape.

The Early Years: Silent Films in Monochrome

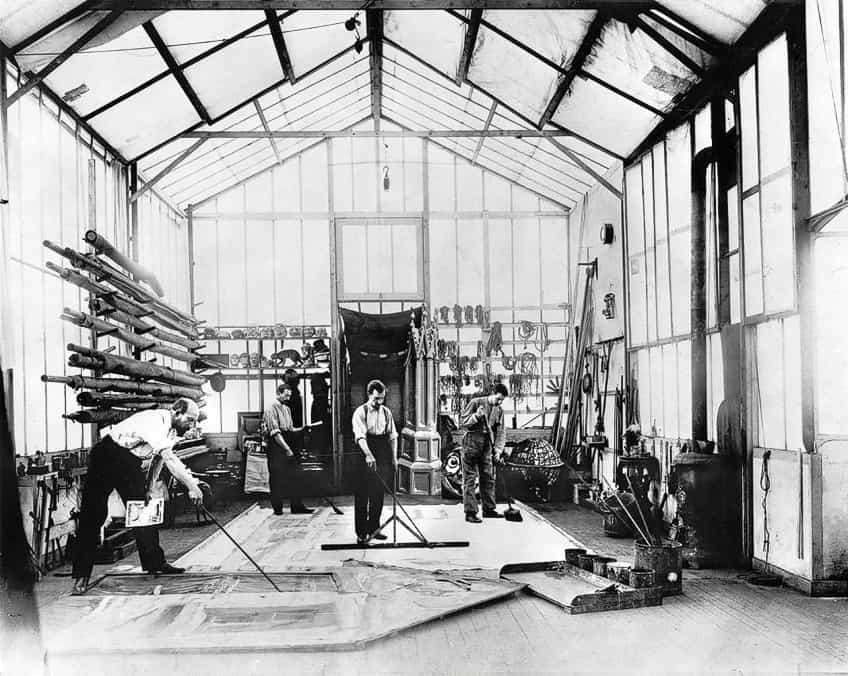

When cinema first emerged in the late 19th century, the medium was universally coated in black and white, as characterized by silent films. These early cinematic works relied heavily on the power of visual storytelling, as sounds had not yet become part of the cinematic experience. Pioneering directors like Georges Méliès, F.W. Murnau, and D.W. Griffith utilized dramatic lighting, innovative camera techniques, and inventive set designs to convey narrative and emotion.

In these early days, color in cinema was a rarity, and when it did appear, it was often hand-painted onto individual frames. Hand-coloring was a labor-intensive process that involved artists meticulously applying color to black-and-white footage. These techniques were used to create special effects or emphasize key elements in films, but they were far from mainstream.

The Advent of Two-Color Technicolor

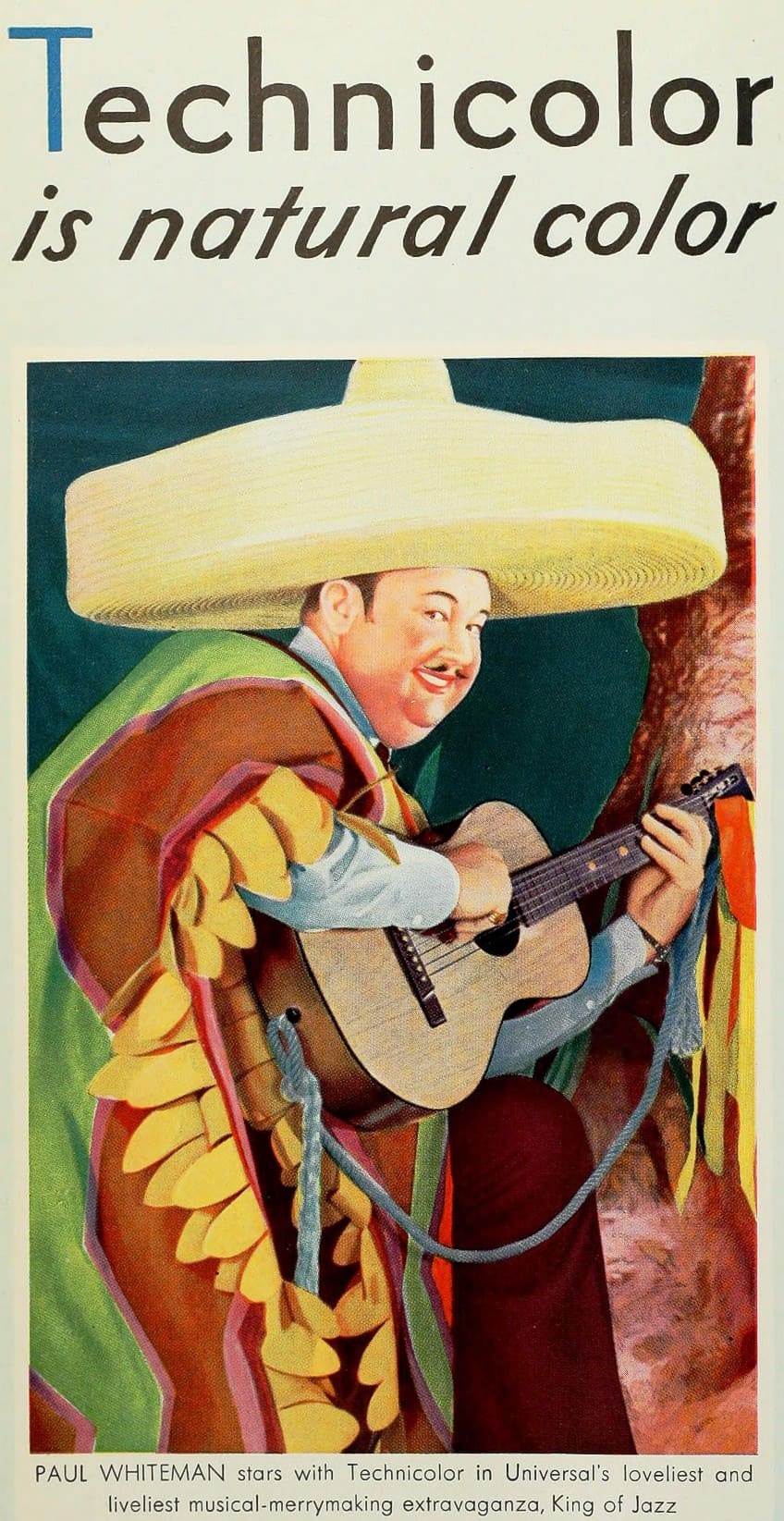

As the 1920s rolled in, a breakthrough occurred with the introduction of the two-color Technicolor process. This revolutionary development, pioneered by George Albert Smith and Charles Urban in 1908, added a degree of color to the cinematic experience. Two-color Technicolor relied on red and green filters to create a more realistic color effect, and it represented a significant step forward in the journey from black and white to color.

Notable films that embraced this technology included The Toll of the Sea (1922) and The Black Pirate (1925).

These movies showcased the potential of two-color Technicolor but also highlighted its limitations. It could not reproduce the full spectrum of colors, often resulting in a somewhat limited and stylized appearance. Because of this, filmmakers had to adapt their sets and costumes to suit the technology, and careful lighting was essential for the process to work effectively. Nonetheless, two-color Technicolor marked a crucial milestone in the progression toward color cinema.

The Introduction of Three-Color Technicolor

In the 1930s, the game-changing development was the introduction of three-color Technicolor. This new process, perfected by engineers like Herbert Kalmus, allowed for the separate recording of red, green, and blue channels. This advancement enabled the full range of colors to be captured on film, making it possible for audiences to see the world in all its colorful glory.

Becky Sharp (1935) became the first feature film to utilize the three-color Technicolor process, opening a new era of color cinema. With the introduction of three-color Technicolor, cinema was forever transformed, and a new world of artistic possibilities emerged.

The Artistry of Color in Film

The introduction of color in cinema was not merely a technical achievement; it was also a storytelling tool that allowed filmmakers to convey emotions, moods, and themes in new and creative ways. Color could be symbolic, with different hues representing various elements within a narrative. One of the most iconic examples of the use of color in storytelling is The Wizard of Oz (1939), directed by Victor Fleming. The film famously transitions from sepia-toned Kansas to the vibrant, Technicolor world of Oz. This shift in color emphasizes the transformation of Dorothy’s journey from the ordinary to the extraordinary. The use of color in The Wizard of Oz remains a symbol of the enchantment and transformative power of color in storytelling.

Musicals, a genre known for its spectacle and song-and-dance numbers, thrived in the color world of cinema.

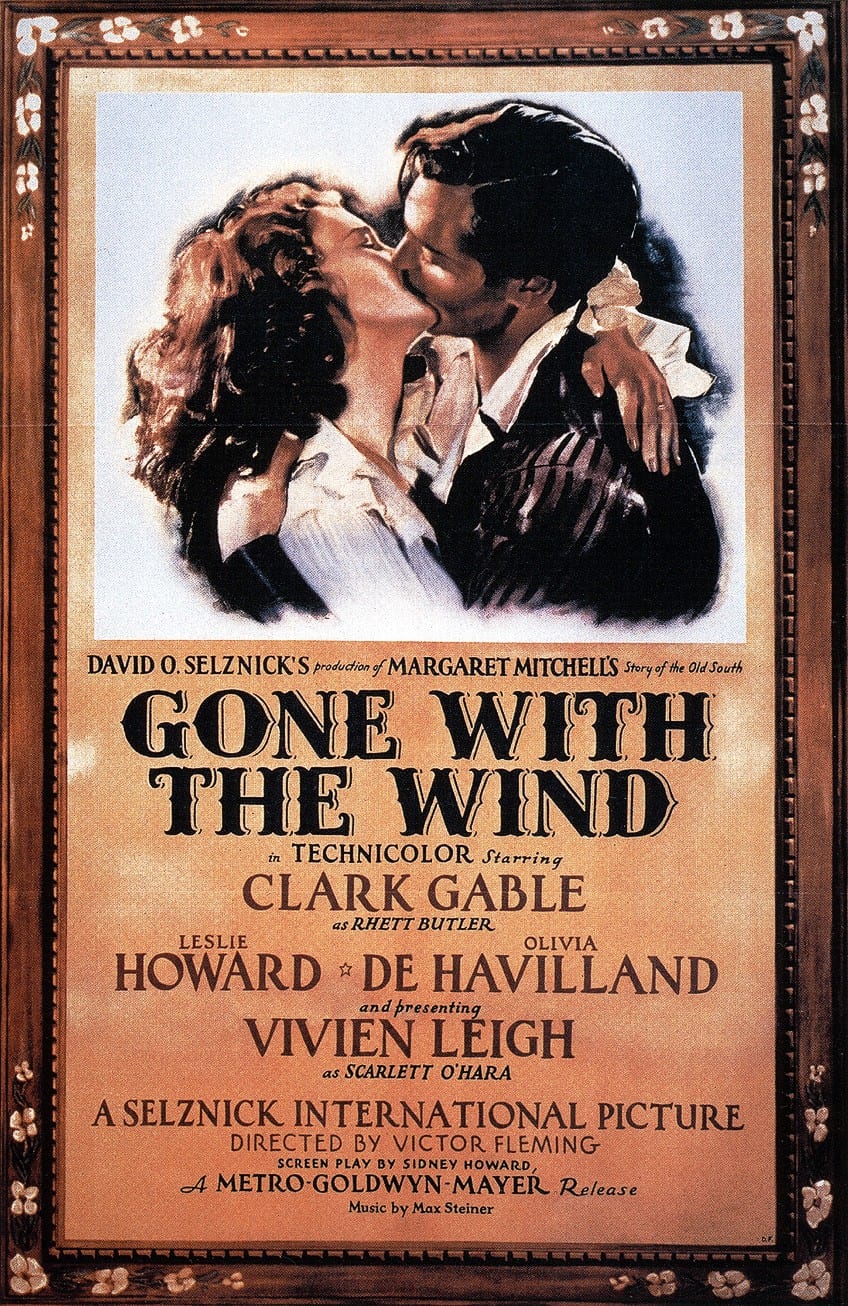

Vibrant films like Singin’ in the Rain (1952), directed by Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, and An American in Paris (1951), directed by Vincent Minelli, used color to enhance the storytelling experience. Color became an integral part of these musicals, immersing audiences in the joy and exuberance of the performances. Historical epics also benefited from the introduction of color. Gone with the Wind (1939), directed by Victor Fleming, and Ben-Hur (1959), directed by William Wyler, used color to recreate the grandeur of their respective time periods. Color added depth and richness to these cinematic masterpieces, making them visually captivating and historically immersive.

Challenges and Artistic Choices

While the transition to color in cinema was a significant milestone, it was not without its challenges. Early color processes, including two-color and three-color Technicolor, required specialized equipment and expertise. These limitations resulted in higher production costs, limiting the usage of color to major studios and big-budget productions.

Interestingly, not all filmmakers immediately embraced color. Even when color technology was readily available, renowned directors like Alfred Hitchcock continued to use black and white as a stylistic choice. Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), for instance, is a classic example of how black and white can be used to create mood and atmosphere, emphasizing the enduring artistic appeal of monochrome.

The Digital Age and Beyond

The digital age has ushered in a new era of color cinema. With advancements in digital filmmaking and computer-generated imagery (CGI), filmmakers now have more control and flexibility in creating vibrant and imaginative worlds. The transition from black and white to color is no longer constrained by the limitations of film stock, allowing for even more creative storytelling. Contemporary films, such as the visually stunning Avatar (2009), directed by James Cameron, showcased the potential of color in storytelling.

The film uses a sophisticated combination of live-action and CGI to create a lush and visually captivating alien world.

What Was the First Movie Shot Entirely in Two-Color?

When asked, “Was The Wizard of Oz the first color movie?”, many people would instinctively say yes due to how the film was able to popularize the use of color at the time, marking a defining moment in film history that can still be felt today. However, while The Wizard of Oz was indeed pivotal in allowing color to become a mainstay in the production of film, large portions of the film were presented in a sepia tone, relating to the conformity and reclusive nature of Kansas, our main character’s hometown.

It was actually 25 years prior that the world’s first full-color, feature-length, pioneering masterpiece was originally released, a groundbreaking moment that changed the course of cinematic storytelling forever. The World, the Flesh, and the Devil is that pioneering masterpiece, a film that not only captured the vibrant hues of life, but also ventured into uncharted territory by pushing the boundaries of cinematic artistry.

The World, the Flesh, and the Devil: A Colorful Vision Takes Shape

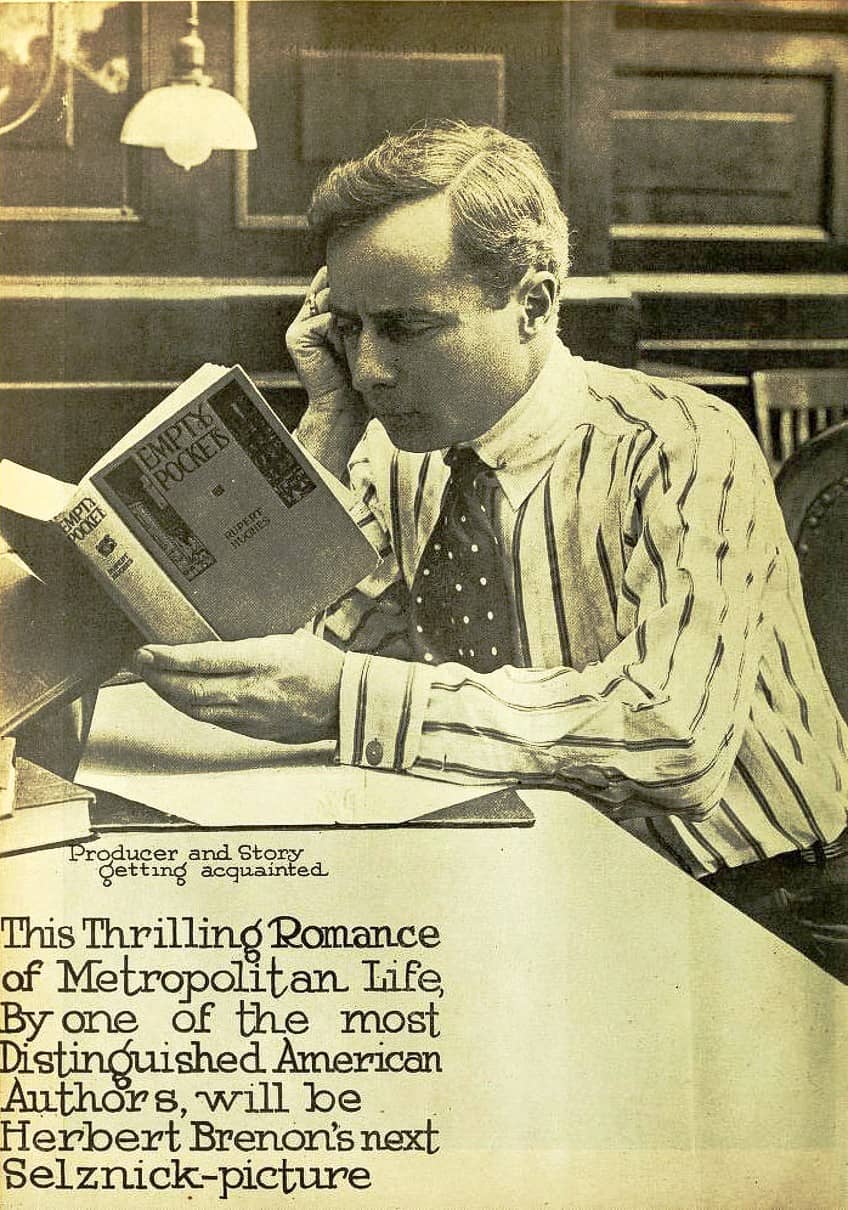

It was the year 1914 when The World, the Flesh, and the Devil came to life. At a time when the film industry was still in its infancy, the idea of capturing an entire feature-length film in color was nothing short of revolutionary. Directed by the pioneering filmmaker, Herbert Brenon, the movie was based on a novel by Nelson Lloyd and told the tale of temptation and redemption, bringing to life the bustling backdrop of New York City in a way that had never been seen before. What made this film truly groundbreaking was its use of the two-color Kinemacolor process, an early color technology developed by George Albert Smith and Charles Urban. Kinemacolor utilized alternating frames in red and green to create the illusion of a full spectrum of color. While not as sophisticated as modern color processes, it was a giant leap forward in capturing a more vibrant and lifelike quality on film.

The World, the Flesh, and the Devil was a masterpiece in its own right, using color not just as an aesthetic enhancement but as an integral storytelling device.

It employed color to underscore the emotional and thematic elements of the narrative, bringing depth and richness to the characters and their experiences. The lush greens of Central Park, the bustling reds of the city streets, and the symbolic hues of the characters’ costumes all contributed to the film’s emotional and narrative resonance. The film’s success was not only a technical feat but also a cultural milestone. In the early 20th century, cinema was emerging as a powerful art form that could mirror the complexities of human life. The World, the Flesh, and the Devil resonated with audiences, adding a new layer of depth to storytelling, and symbolizing the dawning of a new era in cinema. This pioneering use of color influenced the future of filmmaking in profound ways.

It opened the door for further exploration of color as a storytelling tool, paving the way for the development of more advanced color processes, such as Technicolor. Today, we often take for granted the vibrant spectacles that grace our screens, but it was not always so. The World, the Flesh, and the Devil serves as a reminder that the path to progress is often marked by bold innovation. This film’s legacy is a testament to the creativity and daring spirit of the pioneers who dared to dream in color, reshaping the course of cinematic history. This was a groundbreaking achievement that forever changed the cinematic landscape. It was the first feature-length film shot entirely in two-color, utilizing the two-color Kinemacolor process to create a more vibrant and immersive storytelling experience.

This pioneering film opened the door to the further exploration of color as a powerful tool in filmmaking, setting the stage for the color cinematic landscapes we enjoy today.

What Was the First Movie Shot Entirely in Three-Color?

In the early days of cinema, black-and-white and two-toned films reigned supreme, weaving stories that captured hearts and minds. However, a monumental shift was on the horizon, the transition to full, three-color Technicolor. This transformative leap in cinematic storytelling found its first feature-length milestone in Becky Sharp, a groundbreaking film released in 1922. It was the first movie ever to be filmed entirely in full, vivid, and glorious three-color Technicolor. “Becky Sharp” ushered in a new era of visual storytelling, enriching the cinematic experience and shaping the trajectory of filmmaking history.

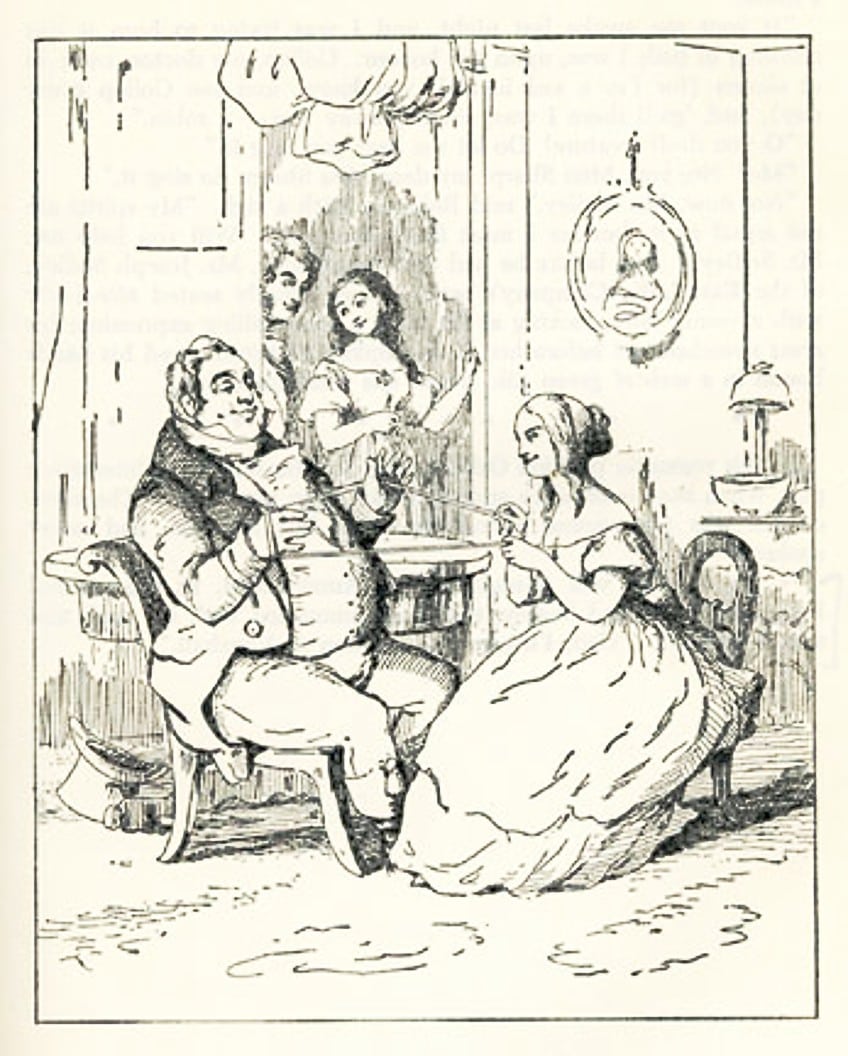

Becky Sharp: A Pioneering Triumph in Full Color Cinema

Directed by Lewis J. Selznick, Becky Sharp was a pioneering film that showcased the immense potential of three-color Technicolor. This process involved capturing images through three separate lenses, each of which were equipped with color filters. These separate color records were then expertly combined in post-production to create a full range of colors, resulting in a vibrant, true-to-life palette that was unprecedented in cinema. The release of Becky Sharp marked a momentous evolution in film technology, unleashing a vibrant spectrum of colors onto the screen. Audiences were transported to a world that mirrored reality more closely, making cinematic storytelling an even more immersive and captivating experience.

This full-color breakthrough expanded the filmmaker’s toolkit, allowing them to not only convey tich, visual landscapes but to amplify the emotional and narrative resonance of their stories.

Becky Sharp was not merely a technical achievement; it was a cultural and artistic milestone. As color cinema emerged, it symbolized a world in transition, where artistic innovation intersected with the emotional depth of storytelling. The film stood as a testament to progress, imagination, and the potential of color to transform cinematic narratives. The shift from black-and-white to full-color cinema was a monumental transition, and Becky Sharp was at the forefront of this revolutionary movement. As audiences marveled at the rich tapestry of colors on the screen, filmmakers began to recognize the artistic and commercial possibilities that color could offer. No longer was it a question of whether to embrace color but rather how to harness its power effectively.

The impact of Becky Sharp reverberated far beyond its release, influencing the future of filmmaking. This pioneering film inspired a generation of filmmakers to embrace the full spectrum of colors, deepening the storytelling and emotional resonance of their works. The visual richness of three-color Technicolor became an integral part of cinematic storytelling, transforming it into a vivid and immersive medium. As the very first feature-length film shot entirely in three-color Technicolor, Becky Sharp stands as a monumental achievement in the world of cinema, one that marked a turning point like no other in filmmaking history. This cinematic triumph paved the way for the emergence of full-color storytelling, where the vibrancy and richness of the palette were harnessed to amplify the emotional and narrative resonance of films. Becky Sharp is a testament to the enduring power of cinema to inspire, captivate, and innovate, leaving an indelible mark on the art of storytelling in film.

It serves as a reminder that the world of cinema is a canvas of limitless possibilities, where creativity, technology, and storytelling converge to create transformative moments in the history of film.

What Was Hand Colorization in Movies?

In the early days of cinema, the silver screen was a canvas painted only in shades of black and white. Audiences were captivated by the art of storytelling, yet filmmakers yearned for a way to infuse color into their narratives. The answer came in the form of hand colorization, a meticulous and artistic process that transformed monochrome films into vibrant, captivating tales.

The Genesis of Hand Colorization

As early filmmakers and audiences alike desired to see their stories in color, the solution to this challenge emerged through the technique of hand colorization. This process involved painstakingly painting individual frames of black-and-white films with watercolors or oil-based dyes to introduce color to specific elements within a scene. The artists responsible for this labor-intensive craft applied pigments frame by frame to objects, characters, or settings.

This method allowed filmmakers to make particular elements stand out or convey symbolism, thus enhancing the film’s storytelling.

When asked about what was the first movie in color, a true cinephile may refer to one of the earliest known instances of hand colorization in cinema, which can be traced back to the early 1900s. Georges Méliès, the legendary French filmmaker renowned for works like A Trip to the Moon, frequently utilized this technique to bring his fantastical visions to life. His films featured hand-painted frames that vividly showcased his imaginative worlds in color, captivating audiences and establishing him as an early pioneer of the craft.

The Craft of Hand Colorization

Hand colorization was an intricate, labor-intensive process, demanding the utmost skill and patience. Gifted artists would painstakingly apply color frame by frame, meticulously adding life and vibrancy to the film. These artists were the original colorists, employing brushes, pigments, and their artistic intuition to transform cinema into a visually captivating medium.

One of the techniques employed in hand colorization was the strategic use of color to create a sense of depth and perspective. For instance, a character in the foreground might be painted with brighter, more vibrant colors, while the background could be given a more subdued, cooler tone. This created a sense of visual hierarchy, drawing the audience’s attention to the most crucial elements of the scene.

The Lumière Brothers and La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon

The Lumière Brothers, Auguste and Louis Lumière, are known as pioneers in early cinema. Their 1895 film, La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon, is a significant piece of cinematic history, as one of the earliest publicly projected films. To enhance the visual experience, some copies of this film underwent meticulous hand colorization.

While the film may appear rudimentary by contemporary standards, it was a groundbreaking work that displayed the potential for colorization in cinema, even in its earliest days.

Hand Colorization in Silent Films

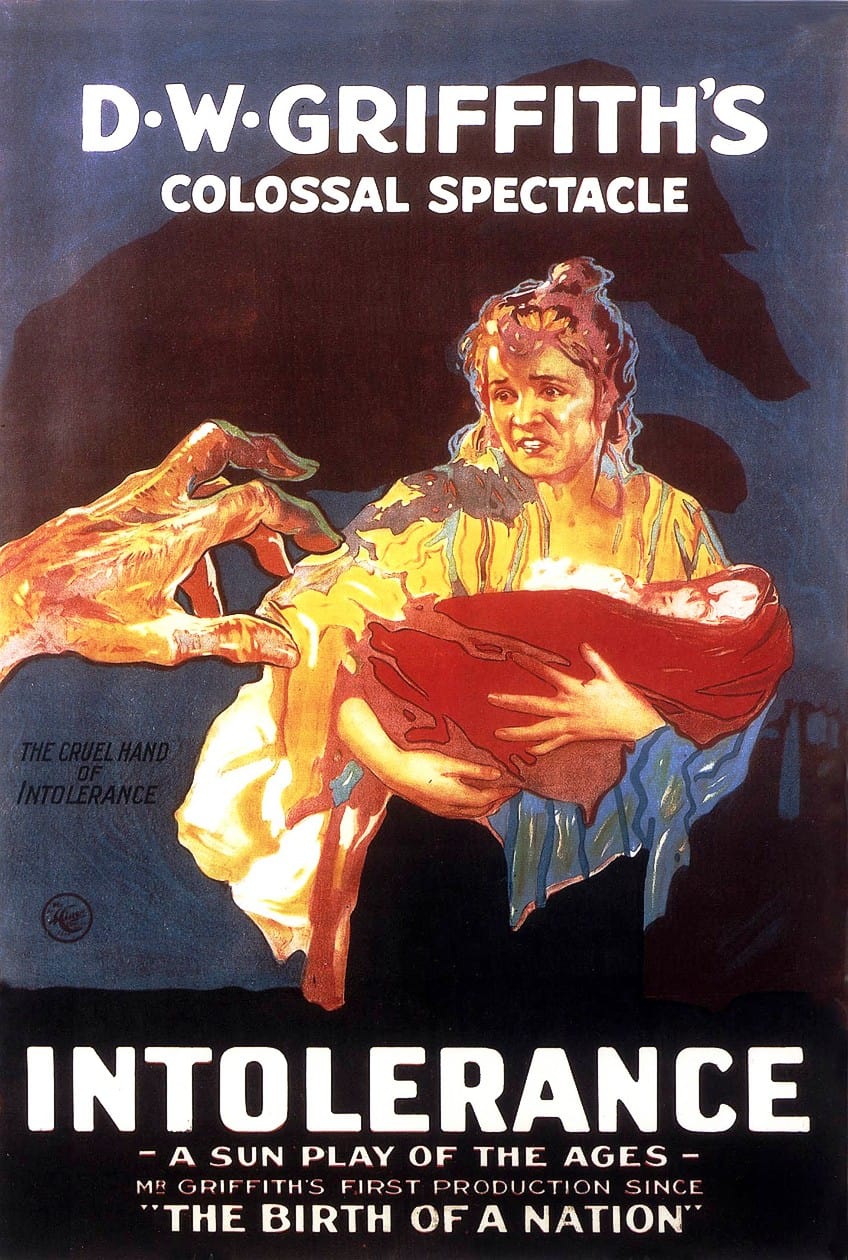

Hand colorization continued to be a popular method in silent films, offering a sense of spectacle and enriching the storytelling. Directors like D.W. Griffith used hand colorization to heighten emotional impact. Griffith’s epic silent film, Intolerance (1916), extensively employed hand colorization to enhance the film’s storytelling, particularly in sequences depicting ancient Babylon.

The Persistence of Hand Colorization

Even as full-color processes like Technicolor emerged in the 1930s, hand colorization endured, particularly in markets with limited access to color technology. Filmmakers in Eastern Europe and Asia continued to employ hand colorization to add vibrancy to their movies.

The iconic 1934 Soviet film, Alexander Nevsky, directed by Sergei Eisenstein and Dmitri Vasilyev, featured hand-colorized sequences that intensified the battle scenes, contributing to the film’s lasting impact.

The Pioneers of Hand Colorization

While the world of cinema rapidly evolved with the introduction of full-color technologies, the legacy of hand colorization endured as a testament to the creativity and dedication of early colorists. These artists played an essential role in the development of cinema, enriching storytelling and enhancing the visual appeal of the medium. Hand colorization, although a labor-intensive and meticulous process, played a pivotal role in bridging the gap between the monochrome era of early cinema and the vibrant, full-color spectacles we enjoy today.

It was a testament to the creativity and dedication of artists and filmmakers who sought to infuse life and vibrancy into the silver screen. Through the meticulous efforts of these early colorists, hand colorization played a crucial role in the evolution of cinema, enhancing storytelling, and contributing to the visual richness of the medium. While technology was advanced, the legacy of hand-colorization endures as a reminder of the artistry and ingenuity that have shaped the world of cinema.

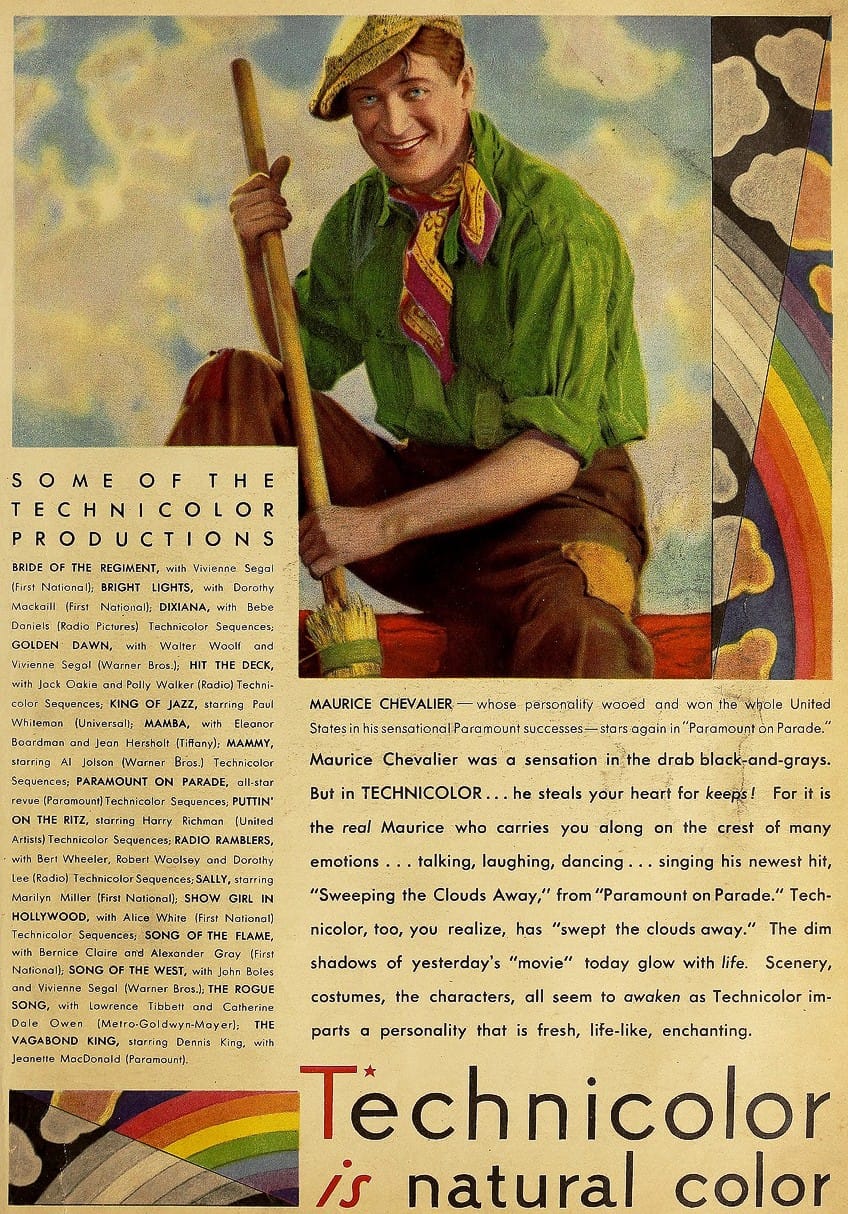

How Technicolor Changed Cinema

In the history of cinema, few innovations have had a more profound and lasting impact than Technicolor. When it burst onto the scene in the 1930s, it not only transformed the way movies were made and watched by also enriched storytelling, cinematography, and the entire cinematic experience as a whole.

The Birth of Technicolor

Before the advent of full-color filmmaking, the motion picture industry primarily relied on black-and-white film stock. The dream of bringing vivid, lifelike colors to the screen had long eluded filmmakers, but that all changed with Technicolor. Developed by Herbert Kalmus, Daniel Frost Comstock, and W. Burton Wescott, the Technicolor process was a groundbreaking leap forward in cinematic technology.

In 1935, the release of Becky Sharp marked the first full-length feature film shot entirely in Technicolor. Directed by Rouben Mamoulian, this adaptation of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair dazzled audiences with its rich, vibrant colors, instantly establishing Technicolor as a force to be reckoned with in the film industry.

The Impact on Storytelling

Technicolor offered filmmakers a powerful new tool for storytelling. Color could now be used not only for visual splendor but to convey a seemingly ever-expanding array of moods, emotions, and themes. This was a game-changer for directors and screenwriters who could now use color to enhance the narrative.

Whether through the symbolism of specific colors, the emotional resonance of a character’s wardrobe, or the depiction of different time periods, Technicolor opened up a world of creative possibilities.

Consider Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz(1939). The film’s use of Technicolor was integral to its narrative structure, with the switch from black and white to color serving as a visual metaphor for Dorothy’s transition from her mundane life in Kansas to the magical world of Oz. This transformation added depth and meaning to the story, making it an iconic part of cinematic history.

Technicolor and Cinematography

Technicolor’s influence on cinematography was equally significant. The three-strip process used in Technicolor allowed for the precise capture of red, green, and blue light, resulting in a more accurate and vibrant color reproduction. The use of these primary colors in the Technicolor process contributed to the medium’s vividness and realism.

Cinematographers and directors could now experiment with color palettes, lighting, and composition to create visually stunning and emotionally resonant scenes. Victor Fleming’s other 1939 marvel, Gone with the Wind, co-directed by Goerge Cukor, showcased the full potential of Technicolor in capturing the grandeur of the American South. The film’s lush and sweeping landscapes, colorful costumes, and vivid sunsets contributed to its visual splendor, making it a true masterpiece of color cinematography.

The Magic of Musicals

Musical films were among the first to embrace Technicolor, taking full advantage of the process to create spectacular, immersive experiences. The marriage of music and color proved to be a match made in cinematic heaven. Musicals like The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Claude Rains, used Technicolor to enhance the enchanting and adventurous elements of the film.

The richly colored costumes, swashbuckling action, and lavish sets were all brought to life with the brilliance of Technicolor.

Perhaps the most iconic Technicolor musical of all time is Singin’ in the Rain (1952), directed by Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly. The film not only boasted memorable songs and dance numbers but also showcased the vibrancy of Technicolor in its joyous and energetic sequences. The color, combined with the exuberance of the performances, created an unparalleled cinematic experience.

Expanding Genre Horizons

The introduction of Technicolor also led to the growth of genres that were perfectly suited to color cinematography. Epic historical dramas, fantasy, adventure, and romantic films found Technicolor to be a new medium in which to express their grandeur and extravagance.

Ben-Hur (1959), directed by William Wyler, exemplified the potential of Technicolor in epic historical dramas. The film’s vivid depiction of ancient Rome, chariot races, and grand battles was enhanced by the brilliance of Technicolor. The use of color created a visual spectacle that contributed to the film’s monumental success.

The Transition to Full Color

Technicolor played a pivotal role in bridging the transition from black-and-white to full-color cinema. As the film industry began to adopt full-color processes, Technicolor had already set the standard for what color in films should look like.

This legacy influenced the development of newer color technologies and set the bar for the vibrant and lifelike colors that audiences expected to see on screen.

Technicolor’s Enduring Legacy

Despite the evolution of cinematic technology and the eventual decline of the original Technicolor process, its legacy endures in the hearts and minds of filmmakers and audiences alike. Technicolor transformed cinema by providing filmmakers with a powerful tool for storytelling and cinematography. Its impact is seen not only in the films it directly influenced but also in the way it shaped the expectations of viewers, setting the standard for the quality of color in film.

Closing off, Technicolor revolutionized cinema by introducing the magic of color to the silver screen. It enriched storytelling, offered new opportunities for cinematography, and opened doors to the creative exploration of color in cinema. Through the brilliance of Technicolor, filmmakers and audiences alike experienced a transformation that forever changed the world of cinema, and continues to inspire filmmakers to this day. Technicolor’s legacy is a vibrant and enduring testament to its lasting impact on the art of storytelling in film.

Frequently Asked Questions

When Were Movies Made in Color?

The first experiments with color in motion pictures date back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, it was not until the 1930s that full-length feature films in color, particularly using the three-color Technicolor process, began to emerge. The early 1930s marked the beginning of the color revolution in cinema.

What Was the First Movie in Color?

The first full-length feature film shot entirely in color was Becky Sharp, which was released in 1935. Directed by Rouben Mamoulian, this film marked a significant milestone in cinematic history, as it used the early three-color Technicolor process.

Duncan completed his diploma in Film and TV production at CityVarsity in 2018. After graduation, he continued to delve into the world of filmmaking and developed a strong interest in writing. Since completing his studies, he has worked as a freelance videographer, filming a diverse range of content including music videos, fashion shoots, short films, advertisements, and weddings. Along the way, he has received several awards from film festivals, both locally and internationally. Despite his success in filmmaking, Duncan still finds peace and clarity in writing articles during his breaks between filming projects.

Duncan has worked as a content writer and video editor for artincontext.org since 2020. He writes blog posts in the fields of photography and videography and edits videos for our Art in Context YouTube channel. He has extensive knowledge of videography and photography due to his videography/film studies and extensive experience cutting and editing videos, as well as his professional work as a filmmaker.

Learn more about Duncan van der Merwe and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Duncan, van der Merwe, “What Was the First Movie in Color? – A Technicolor Triumph.” Art in Context. November 16, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/what-was-the-first-movie-in-color/

van der Merwe, D. (2023, 16 November). What Was the First Movie in Color? – A Technicolor Triumph. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/what-was-the-first-movie-in-color/

van der Merwe, Duncan. “What Was the First Movie in Color? – A Technicolor Triumph.” Art in Context, November 16, 2023. https://artincontext.org/what-was-the-first-movie-in-color/.