Brutalist Architecture – A Look at the Development of Brutalist Design

What is Brutalism architecture and what is the Brutalism definition? Brutalist design is an architectural form distinguished by purposeful simplicity, crudeness, and clarity, which can be regarded as severe and intimidating. The success of these Brutalist buildings was both stunning and divisive, due in part to their focus on the utilization of unpainted concrete for building facades and surfaces. Brutalist house design arose after WWII, although it was founded on the concepts of utilitarianism and tremendous austerity that characterized the preceding architectural modernism.

Exploring Brutalist Architecture

Brutalist architecture attempted to adapt older concepts to a post-war reality in which urban rebuilding was an urgent requirement. In this way, it was influenced by democratic-socialist notions of society, but it was also pushed by the avant-garde eccentricities of rogue designers, and it is known for the bravado of its brutalist design as much as for its socially democratic attitude.

Brutalist buildings became associated with urban squalor and decay in the decades after their peak, owing partly to their usage in massive social housing developments. However, in the 21st century, Brutalist house design and Brutalist interior design are firmly back in critical and public favor.

The Origins of Brutalist Architecture

For the architects of Brutalist buildings, this technique demonstrated a reality to the textural aspects of materials and labor that exemplified their socially involved, ethics-driven attitude to work. Brutalism arose at a period when the large-scale, cheap residential design was desperately needed. The main cities of Europe were brutally bombed and there was a necessity to remove urban squalor, as well as a general desire to alleviate the condition of the average citizen.

This sparked large-scale rehousing programs across most of the continent.

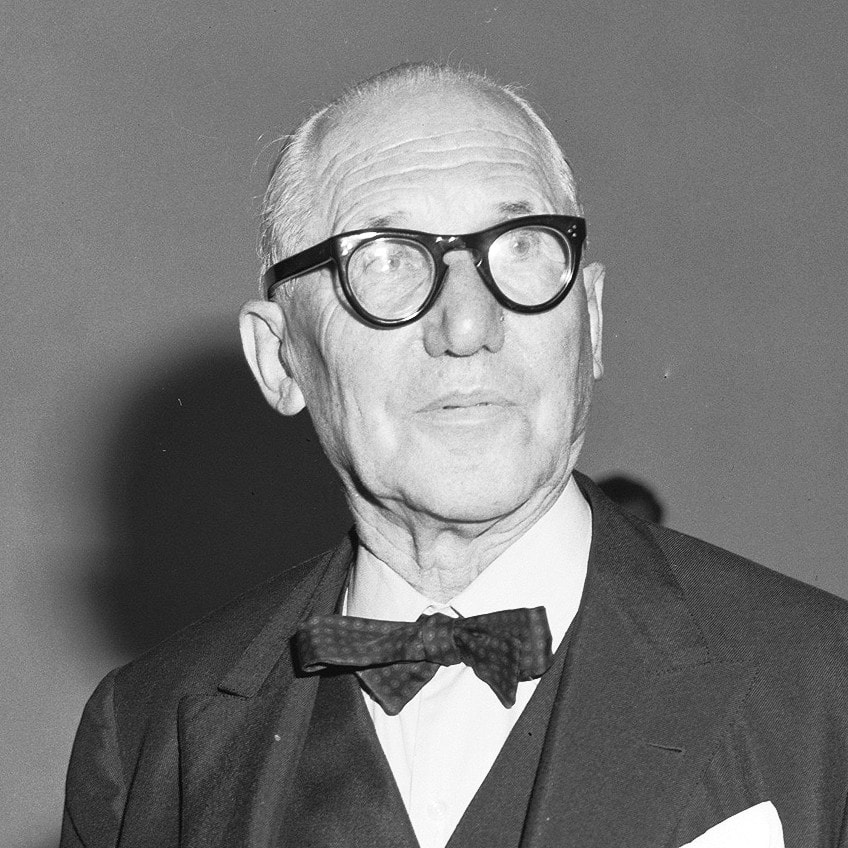

Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier, a contemporary architectural pioneer, was not only the key precursor of and impact on Brutalism, but he also designed some of its most recognizable structures. He originally examined the usage of concrete as a pupil under Auguste Perret in Paris, then researched reinforced concrete technologies with engineer Max Dubois in 1914.

“Reinforced concrete presented me with great resources, diversity, and a passionate plasticity,” Le Corbusier said.

His early concept for the Dom-Ino House (1915), an unbuilt prototype for post-World War I temporary dwellings, featured a concrete modular construction for which tenants could create their own external walls using materials stockpiled on site. He characterized it as “a juxtapose technique of building based on an endless number of plan combinations”.

His apartment building Unité d’Habitation (1952) in France was regarded as the first instance of Brutalism in urban development, while his Maisons Joule (1951-1955) impacted the movement’s attitude to individual Brutalist houses.

However, Le Corbusier did not connect with the word “Brutalism” ideology and was offended when his work was labeled as part of it.

Villa Göth

Elis Göth, a scientist from Sweden commissioned Lennart Holm and Bengt Edman and to design him a private mansion in Uppsala in 1949. The villa was a two-story rectangular structure made of rich brick, with visible I-beams and a variety of béton brut ceilings and walls exposing the concrete casting forms.

The building was described as “New Brutalism” by Hans Asplund, a famous Swedish architect.

British Brutalist Architecture

Several British architects who explored Villa Göth, notably Oliver Cox and Michael Ventris, picked up on the “New Brutalism” label and introduced it back home, where it spread rapidly. Because of this, brutalism is still occasionally called New Brutalism. Due to this self-conscious adoption of the word by British designers and writers, Britain, and particularly the Smithsons’ architecture, became firmly identified with Brutalism.

Reyner Banham termed Brutalism “Britain’s first local art movement” in a 1951 essay, claiming that the phrase started with Le Corbusier’s support of raw concrete and Art Brut.

Bonham said that Asplund’s “Neo-Brutalism” prioritized aesthetics rather than the principles highlighted by New Brutalism. Two years later, in 1953, Alison Smithson, an English architect, introduced the phrase “Brutalism” in Architectural Design to characterize her concept for a Soho property that was to be “exposed totally, minus interior trimmings wherever practical.” “Had this been erected,” she said, “it could have been England’s first exemplar of New Brutalism.”

Brutalism became so strongly connected with the Smithsons’ architecture that photographer Georges Candilis said it was a neologism developed by merging a combination of Alison Smithson’s given name, “Al,” with Peter Smithson’s moniker “Brutus.” Peter and Alison Smithson met at Durham University and established a lifetime personal and professional connection. They won an architectural competition in 1949 for their design of the Hunstanton Secondary Modern School (1954) in Norfolk, which was later regarded as an example of Brutalist architecture.

Indeed, the two swiftly rose to prominence as pioneers of the new movement, thanks to partnerships with designers at the London Institute of Contemporary Arts and membership in Team 10, a collection of architects who advocated for a new philosophy of urban planning.

The Smithsons published essays promoting the use of unfinished concrete, exposed building structures, and low-cost manufactured materials to produce buildings tailored to specific settings. Placing the Brutalist movement from a historical perspective, they highlighted Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s earlier stuff, Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture, and traditional Japanese architecture as inspirations, citing “a regard for the natural environment, and from that, for the materials of the created world.”

Their views were influenced by the social and economic realities of postwar Britain, which necessitated large-scale reconstruction in many extensively devastated towns – they defined their strategy as “make do and repair.”

Team 10

The organization identified itself as “a modest intimate group of architects who have found each other because each has discovered the assistance of the others important to the growth and comprehension of their own particular work”.

They fought against the focus on transplantable utilitarianism that had characterized the initial stages of modernist architecture in support of urban planning that represented the lifestyles of individual communities and generated community.

As Alison Smithson put it, “Belonging is a fundamental emotional urge. Its connections are of the most basic kind. The nourishing sense of neighborliness stems from ‘belonging.’ Where extensive rehabilitation typically fails, the slum’s small, narrow street thrives”.

The Smithsons created “The Doorn Manifesto” during a 1954 Team 10 meeting as a statement of their collaborative architectural ethics: “it is meaningless to examine the home except as a component of a collective”, the manifesto claimed. It also includes their famous expression “streets in the sky”, which refers to elevated pathways with access to high-rise flats as a means of fostering communal life in high-density living.

Team 10 remained significant in the subsequent decades, both in the global rise of New Brutalism and in the establishment of Structuralism, a style founded by architects Jacob Bakema and Aldo van Eyck.

Styles and Concepts

Brutalism was part of a larger movement of practical design in the mid-century. Unlike modernism in visual art and literature, which is often affiliated with conceptions of sheer complexity, this mid-century modern architecture was remarkable for the recognizable simplification of its design features, as well as its inclusive focus on mass production and functionality, an aesthetic ingrained in the Constructivism and Bauhaus advances.

The focus on brutal materiality that marked the Art Brut movement probably influenced Brutalism.

Streets in the Sky

The notion of “streets in the sky” was a prominent architectural component of Brutalism in the 1960s, including elevated pathways connecting raised residential buildings to provide a sense of community. Golden Lane Estate (1952), an unbuilt development that provided the inspiration for the Smithsons’ Robin Hood Gardens in London, was an early instance of its utilization.

According to the architects, the Golden Lane complex was designed to comprise two apartment towers angled around a stress-free center zone, a tranquil green heart that all homes enjoy and can gaze at.

Each apartment building had elevator silos that connected to open-air walkways. An example – a display of a more delightful way of living in an old industrial sector of a city,” the Smithsons said of the project. In the ensuing decades, this Brutalist paradigm for social interaction was widely used in British public housing, most notably in East London’s Trellick Tower (1972).

Hulme Crescents (1972) in Manchester was the greatest of the British street-in-the-sky projects, but it was demolished in 1994 due to architectural issues.

In the 1970s and succeeding decades, many of these complexes became defined by neglect, poor maintenance, and criminality, and faced popular and critical opposition, until a recent resurrection of cultural and societal goodwill.

University Architecture

Many institutions, particularly in the United Kingdom, gravitated toward Brutalist design in the late 1950s, partly because of its low cost and speed of construction, and partly because of its strong identification with the postwar period’s expanding public and cultural domain.

The Yale Art and Architecture Complex was one of the most well-known early versions in the United States.

Brutalism in North America

Brutalism was a prominent style in the United States from 1962 to 1976, and it was used not only for university structures but also for libraries, government facilities, houses of worship, and corporate offices, especially those of scientific and technological firms. As indicated by Le Corbusier’s contribution to creating the United Nations Headquarters in New York City (1952) alongside Wallace Harrison, Oscar Niemeyer, and Max Abramovitz, a few well international architects were commissioned to create structures in East Coast cities.

Paul Rudolph was regarded as America’s foremost Brutalist architect, and his philosophy and work as a Yale architecture professor impacted succeeding architects.

Several North-American Brutalist designers, all of whom were headquartered in the Midwest, including Ralph Ranson, Evans Woollen III, and Walter Netsch. During the 1960s and 1970s, Ranson created churches, theaters, and the Cedar Square West housing development in his home in Minnesota. Woolen created so many structures in Indianapolis that he was nicknamed “the city’s designer”.

The Brazilian Paulista School

Brazil was a hotbed of Brutalist activity, much as it had been for breakthroughs in Concrete and Constructivist Art after WWII. Joo Batista Vilanova Artigas, a São Paulo-based architect, formed the so-called Paulista School in the 1950s, a loose group of Brazilian architects all headquartered in the city who liked exposed concrete, hard edges, and massive scale.

The school developed on the impact of the Brazilian Carioca school, which began in 1935, but began using concrete in the postwar era, with the Brasil-Paraguai Elementary School being a significant early representation of its aesthetics.

Vilanova Artigas started working with concrete for the Morumbi Stadium (1952).

Soviet Bloc Brutalism

Prefabricated concrete was frequently used in the Soviet Union to construct residential complexes, government facilities, and monuments. The government began plans to boost manufacturing and urbanization in the late 1950s, and widespread use of concrete was regarded as a realistic way to create urban housing that reflected Soviet ideals of community life.

These uniform complexes were dubbed “Panelki” in Russia since they were made up of prefabricated concrete panels; nonetheless, they became notorious for their substandard and often never completed amenities.

Nonetheless, the USSR’s government and monumental architecture were frequently inventive, adopting strange structural shapes that were occasionally likened to UFOs or characterized with references to other science-fiction clichés, such as the title “The Buried Robot” given to the House of Soviets (1970). More well-known instances of Brutalist architecture, such as the Georgia Ministry of Highways (1971) blended the use of bare concrete and unpainted surfaces with the influences of Constructivism.

Boidar Jankovic, the head of an architectural school stressed functionalism and the use of bare concrete in Yugoslavia, whereas Brutalism was considered a method to build a national style that embodied modern socialism in other nations, like Czechoslovakia.

Later Developments

When it came to the 1970s architecture period, Brutalism’s link with urban decay and crime was mirrored in the usage of Brutalist locales in films like A Clockwork Orange (1971), a dystopian image of violent, disenfranchised adolescents. Nonetheless, notable Brutalist buildings such as London’s Barbican Estate were completed during this time.

The concept came to an end in the 1980s with the rise of Deconstructivism, but it lived on in popular culture, with notable buildings serving as backdrops for BBC espionage dramas, Cold War films, and modern British dramas such as Misfits (2009-2013).

Brutalism is resurgent in the twenty-first century, as seen by the production of books like This Brutal World (2016). Brutalist architecture has been the subject of conservation movements, while several notable structures have been destroyed despite popular outrage. In a critique of the exhibit Toward a Concrete Utopia, Alexandra Lange stated, “My opinion as to why we now prefer concrete building is simple: it has a physical presence. We want for locations where we can feel the gravity of the planet, even as we absorb design in pixels.”

Famous Examples of Brutalist Architecture

Brutalist design became the form of choice for many of these buildings due to the size of its designs and concentration on low-cost construction materials, with mixed outcomes for its critical and popular fortunes.

The focus on brutal materiality that marked the Art Brut movement probably influenced Brutalism.

Brutalist architects in the United Kingdom, such as Peter and Alison Smithson, were familiar with Jean Dubuffet, the principal proponent of Art Brut, and strove to mimic his basic, visceral style in their projects. Here are our top choices for buildings that represent the best of Brutalist design and Brutalist interior design.

Unité d’Habitation (Marseille, France)

| Year Completed | 1952 |

| Architect | Le Corbusier (1887 – 1965) |

| Medium | Concrete, steel, glass |

| Location | Marseille, France |

Many critics believe this residential complex of modular units, erected on gigantic concrete pylons, to be the beginning of Brutalism. The coarse textures of its surface provide a sense of vibrancy and vitality, while the traces left by the moldings emphasize the production process. With this tower, Le Corbusier invented the vertical garden city notion, which included all of the amenities a person may require within the building itself. Every third floor is a city street, with stores, restaurants, recreation centers, and preschool programs, while the roof is home to a gym, jogging track, theatrical stage, and small pool.

Le Corbusier had not finished a single project throughout the 1940s before being commissioned for this one; all of his suggestions for large-scale architectural projects had been denied.

As a result, it was the architect’s first official commission when Raoul Dautry consented to move through with Corbusier’s design for standard-sized dwelling units to be built in war-torn Marseille. He subsequently claimed that his design was influenced by a 1907 trip to the Florence Charterhouse monastery in Italy, where he learned that uniformity leads to perfection and that a man’s whole life is dedicated to making the home the family’s temple. Because each module ran the length of the structure, each unit had a view and a patio on both ends.

Residents may pick from twenty-three various apartment layouts, while Le Corbusier also planned the inside furniture, leaving the homeowner to choose just the interior color. The structure is devoid of ornamentation save for the roof’s ventilation shafts, which were designed to imitate the smokestacks of an ocean liner, a design that Le Corbusier appreciated. The structure elevated Le Corbusier to the position of a premier French architect of the 1950s, earning him the title of Commander of the Légion d’Honneur in 1952.

He went on to design similar “habitations”, and his concept of urban life impacted architects such as Lucio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer, and many others. The structure, which is now home to numerous designers and architects, has also been the scene of art installations.

Hunstanton Secondary Modern School (Norfolk, United Kingdom)

| Year Completed | 1954 |

| Architect | Peter and Alison Smithson |

| Medium | Steel, brick, glass |

| Location | Norfolk, England |

The school’s design, dubbed the “glasshouse” by locals, highlights its long, rectangle, glass-glazed center building, whose steel framework can be seen from afar. The architects merged their attraction to modernism, particularly Mies van der Rohe’s works, with a heavy emphasis on visible structural materials, as seen in the predominant storage tanks and the outer framework, which was filled in with brick but left harshly textured and incomplete on its exposed surfaces.

Because of these characteristics, architectural critics coined the term “New Brutalism” to describe the structure for the first time.

The structure’s design is renowned for its minimalism in this and other ways. It employs steel H-frames that accomplish “something akin to full bi-axial symmetry,” according to Rayner Banham. “Much of the impact of the structure derives from the ineloquence, but absolute uniformity, of such components as the stairs and railings,” Banham said, praising the design for its “virtuous under-designing of its elements.”

On closer study, though, the design reveals a number of unique elements.

The two-story rectangular structure has classrooms on the first level, and the Brutalist interior design makes inventive use of staircase columns to reach no more than three classrooms, limiting noise and disturbing student mobility.

Habitat 67 (Montreal, Canada)

| Year Completed | 1967 |

| Architect | Moshe Safdie (1938 – present) |

| Medium | Steel, concrete |

| Location | Montreal, Canada |

This housing project is made up of 354 precast concrete blocks that are joined by steel wires and arranged in random patterns. The building’s profile, which reaches 12 floors, gives the impression of organic development as if it had grown over time via spontaneous social activities. The duplication of the elemental, geometric shape creates a sense of oneness, but the random arrangement communicates a sense of dynamic energy.

While the complex invokes ancient buildings, it also suggests more modern images, such as Cubist art or even an assembly of Lego blocks used by the architect to make preliminary models.

Moshe Safdie grew up in Israel before relocating to Canada as a youngster with his family. His kibbutz experience, as well as Le Corbusier’s architecture and a Japanese style known as Metabolism that pushed for the employment of organic forms in structures, manifested in intricate webs of modular components, such as Nakagin Capsule Tower, affected him as an architect. Safdie created his design for Expo 67, a World’s Fair held during the centennial year of Canada’s creation in 1867, based on concepts from his thesis at university.

He aimed to design a structure that offers each unit the characteristics of a home – Habitat would be all about landscapes, interaction with nature, and streets rather than corridors.

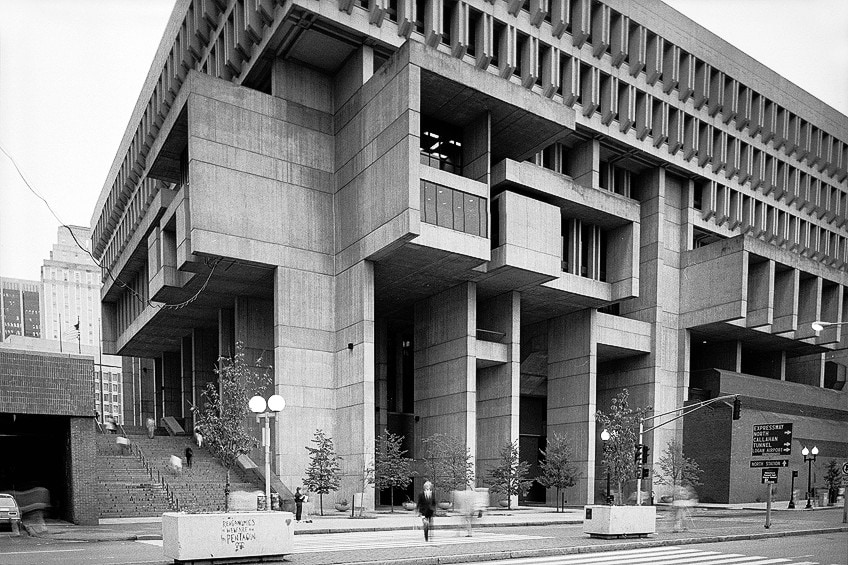

Boston City Hall (Boston, Massachusetts)

| Year Completed | 1968 |

| Architect | Kallmann McKinnel Firm |

| Medium | Brick, concrete, glass |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts |

The many external elements of this structure are made of brick or concrete cast in a variety of designs. They lock together like a jigsaw puzzle, with each piece representing the function of its interior. Public access areas are on the bottom level, partially constructed into a rising fold of land and finished in red brick to match the neighboring brick plaza.

The city council and mayor’s offices are on the second story, which is supported by enormous concrete pylons and features exposed crossbeams, while the administrative offices are on the precast top level, which has tiny windows enclosed by concrete cast molding.

This strong design, like much Brutalist architecture, is an update on the famed architectural modernist concept that style should follow functionality. The concrete for half of the construction was prefabricated in steel molds and utilized a deeper cement, while the remainder was cast on-site in wood beams.

Both were left incomplete to produce color and texture variations, with the second-floor pylons being darker and coarser in look, and the third-floor pylons being lighter and more seamlessly repeated. The inverted pyramid design, which attracts attention downward through the vertical stripes of the window frames to the bottom level, as though highlighting the building’s public purpose, contrasts with the sensation of tone change achieved as the structure ascends.

The structure was divisive from the start, with calls for its destruction commencing while it was still being built. In the decades after its construction, it has often been ranked as one of “the world’s ugliest buildings” in opinion polls.

Polls of architects, on the other hand, have repeatedly determined it to be one of the top 10 design concepts in North America. This disagreement exemplifies the intense and divisive feelings that Brutalist architecture may elicit.

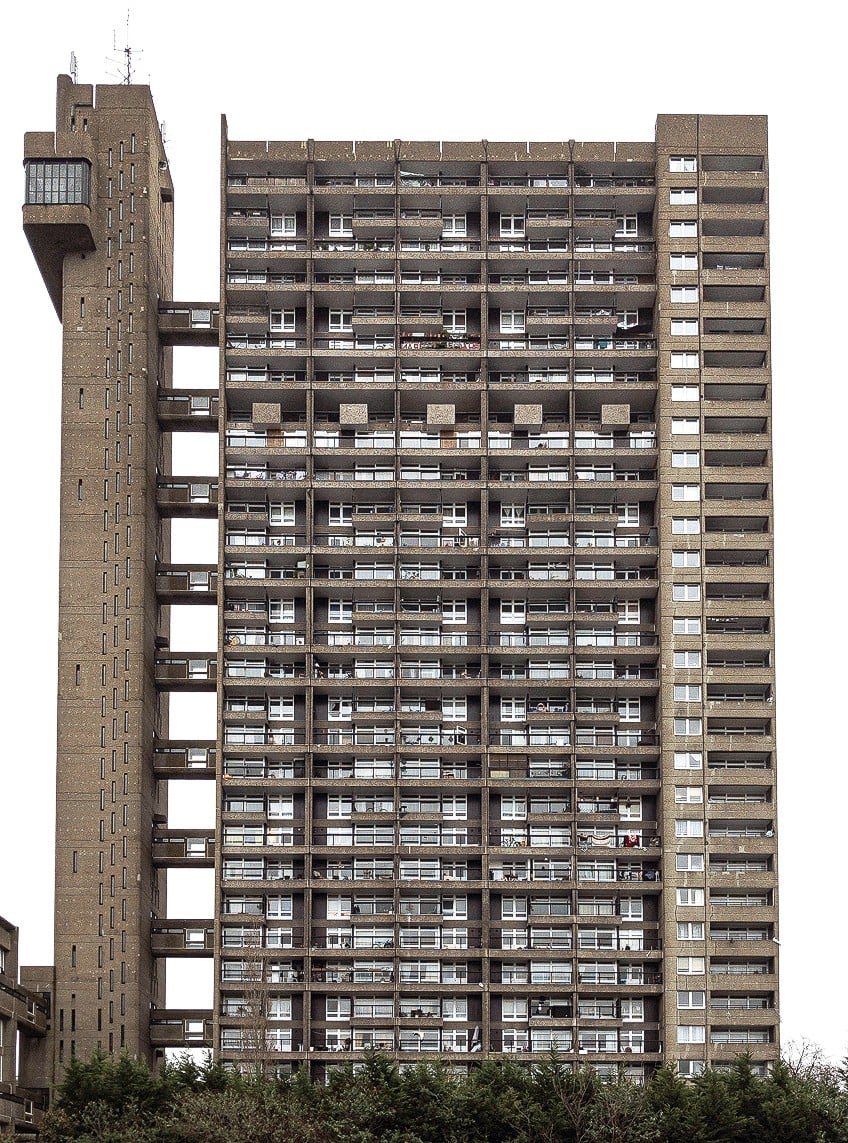

Trellick Tower (London, England)

| Year Completed | 1972 |

| Architect | Ernő Goldfinger |

| Medium | 1902 – 1987 |

| Location | London, England |

Trellick Tower’s 1970s architectural design provides a distinctive and memorable profile, with its left-hand service tower, which includes a lift shaft, connected to the center block on the right by sky bridges. The exposed concrete tower produces a geometric grid of vertical and horizontal lines, which is complemented by the sky bridges’ lines and the utility structure’s soaring verticals. As critic Tim Winstanley put it, “the strong profile dominates the local skyline, suggesting the pure silhouette of a feudal fortress”.

The tower is a bold presence in London’s post-war environment, an expressionistic memorial for the public, with its unapologetic materiality.

The sky bridges appear to catch the sky itself within the building’s lateral and vertical grid since they are defined against the empty distance between two primary components. The gap created by the separation of the two parts will undoubtedly be remembered as Goldfinger’s true accomplishment and a tremendous architectural legacy.

Goldfinger’s design was heavily influenced by his smaller, twin building Balfron Tower (1967), where he stayed for a while and questioned tenants for specifics on how to enhance the structure, expressing his idea that architecture was “something that is only perceptible from within.” Trellick Tower illustrates Goldfinger’s attention to every detail, with features like dual-pane glass to lessen noise, fasteners on the sky bridge to decrease resonance, windows with swiveling mechanisms for easy cleaning, and numerous space-saving functions.

Several instances of vandalism attacked the Trellick Tower shortly after it opened, flooding entire floors and destroying electrical wiring. It became renowned as a high-crime region as a result.

The “tower of horror,” as it was known, emphasized the social concerns connected with Brutalist tower blocks, since the public saw its rugged exteriors as reflecting disadvantaged socioeconomic demographics.

However, in the mid-1980s, the tower’s image began to improve when the government chose to sell some of the apartments to individuals who wanted to live there, resulting in the development of new tenant groups that fought for renovations. It was awarded a Grade II designation in 1998, which is designated for historic structures. Today, the structure is deemed stylish, symbolizing “a fashionable picture of a heavily sedated ghetto that is no longer hazardous,” according to Winstanley.

Brutalism increased in popularity from the mid-20th century until it peaked in the mid-1970s when it came tumbling down as a model of terrible taste. But that’s all shifting now, thanks to a resurgence of interest in and admiration for this once-despised architectural style. Brutalist architecture was predominantly employed for institutional structures and is known for its use of practical reinforced concrete and steel, modular features, and utilitarian atmosphere.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Brutalism?

The Brutalism definition comes from the material used to create it, not from its brutal appearance. Béton Brut is a French phrase that means raw concrete and is also used to characterize the classic architectural style known as Brutalist. Brutalist design is frequently linked to socialist objectives in 20th-century urban philosophy. All of these postwar challenges, as well as the modernist assumption that logical design could yield the finest building, impacted Brutalist architecture. Some feel it must be an instance of postmodern architecture in response to older designs since it is so distinctive, however, this is not the case. It is a study of the simplest workable alternative to a spatial or thematic challenge, as are most modernisms.

What Is Eco-Brutalism?

Eco-brutalism is an architectural style that focuses on the contrast between two opposing concepts: bleak human design and nature’s colorful resiliency. Trees, plants, and other green components are used to transform brutalist architecture into eco-brutalist buildings. These new pieces help to brighten homes and make better use of natural light, yet many people still feel that something is missing. The structures and apartments being constructed in these areas are more aesthetic than functional, which only serves to contrast the brutalist beginnings of the area. They combine ponds and naturally existing greenery into their designs, making use of the inherent tropical environment.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Brutalist Architecture – A Look at the Development of Brutalist Design.” Art in Context. June 15, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/brutalist-architecture/

van Huyssteen, J. (2022, 15 June). Brutalist Architecture – A Look at the Development of Brutalist Design. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/brutalist-architecture/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Brutalist Architecture – A Look at the Development of Brutalist Design.” Art in Context, June 15, 2022. https://artincontext.org/brutalist-architecture/.

Brutalist architecture is very attractive.