Post-Mortem Photography – The Art of Real Victorian Death Photos

The act of capturing the recently departed on film is known as post-mortem photography. Many cultures have embraced the practice of taking post-mortem photos, however, America and Asia have been the most extensively researched. Real Victorian death photos are disturbing remnants from a previous era that offend current sensibilities. In this article, we will look at how and why people took Victorian post-mortem photos.

Table of Contents

The Art of Post-Mortem Photography

Death was ubiquitous throughout the Victorian era due to high mortality rates and the uncontrolled spread of illness. Many individuals devised inventive methods to commemorate the deceased, like Victorian post-mortem photos. While it may seem morbid now, numerous families have used post-mortem photography to remember their loved ones.

“It is not just the image that is wonderful,” Elizabeth Barrett Browning stated as she gazed at a post-mortem photograph, “but the connection and the sensation of closeness involved in the image… the actual silhouette of the person laying there fixed eternally!”

Real Victorian death photos may have been the first exposure to photography for many Victorians. The comparatively new technology allowed them to save a lasting image of their departed family, a lot of whom had never been captured while living. While Victorian post-mortem photos may appear unsettling now, they gave solace during times of mourning for individuals in the 19th century.

The Reasons People Took Post-Mortem Photos

Photography was a novel and fascinating medium in the first half of the 19th century. As a result, the general public desired to record life’s most important events on film. Unfortunately, death was one of the most photographed moments. Most individuals couldn’t hope to live into their 40s due to high death rates. Infants and toddlers were especially susceptible as sickness spread.

In a period before immunizations and medicine, illnesses such as measles, scarlet fever, and cholera were potentially fatal.

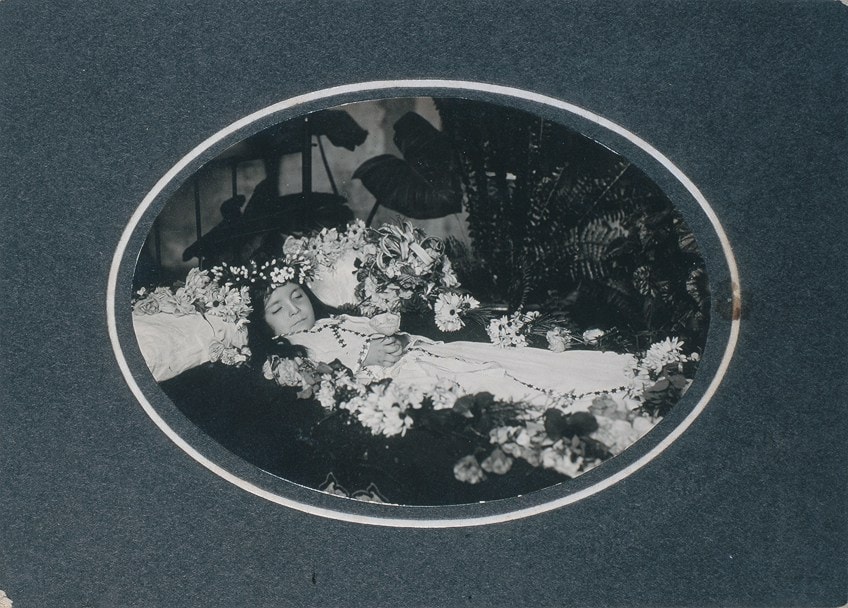

Post-mortem photography provided a new means to memorialize a loved one after death, and many Victorian post-mortem photos served as family portraits in their own right. They frequently represented moms holding their dead babies or fathers looking over their dying offspring.

One photographer recalls parents bringing their stillborn child to his studios. “Can you shoot this?” the mother requested, pointing to a “small face resembling waxwork” buried within a wooden basket. The idea of making a post-mortem portrait predates photography for a long time.

However, in the past, only the richest families could manage to commission an artist to make an artwork of a loved one. People who were less rich might also obtain a post-mortem picture thanks to photography.

Death photographers discovered how to pose youngsters to create the impression of blissful repose, which provided solace to mourning parents. These photographs brought great consolation to bereaved family members. An English novelist, Mary Russell Mitford, observed that her father’s 1842 post-mortem photos “had a divine calm in them”.

How Real Victorian Death Photos Were Taken

Photographing the deceased may appear to be a frightening undertaking. However, because they couldn’t move, dead people were typically simpler to photograph than living ones in the 19th century. Participants had to remain still to generate sharp photographs due to the short shutter speeds of early cameras. When visitors came to visit studios, photographers would occasionally use cast-iron posing platforms to keep them in position.

Because of their absence of blurring, Victorian death photographs are generally straightforward to recognize. After all, the subjects in these photographs did not flinch or move abruptly.

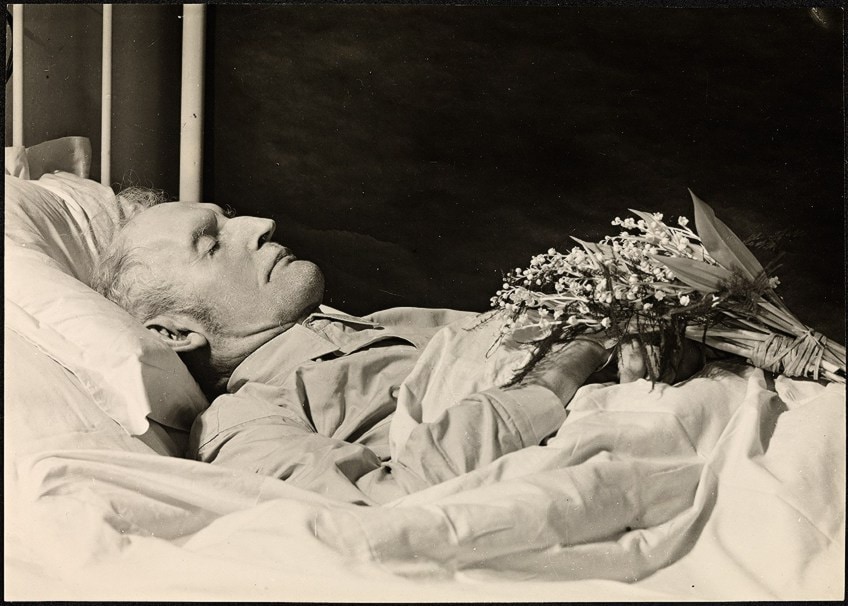

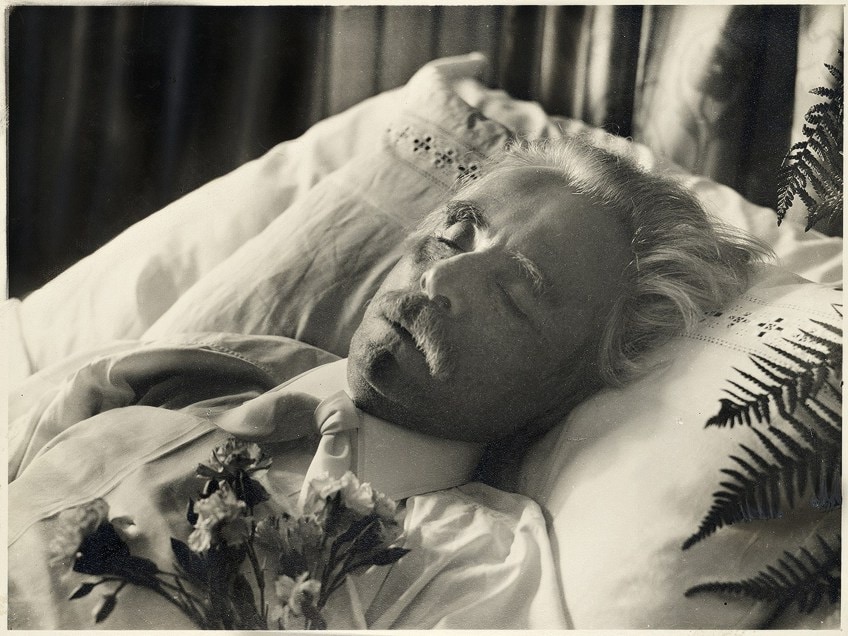

Unlike many photographs, which were frequently done in photo studios, post-mortem images were usually taken in the home of the deceased. As the death portrait craze gained traction, families worked hard to prepare their departed relatives for the session. This might include styling the individual’s hair or clothing.

The photographers and families occasionally embellished the setting to emphasize the aim of the shot. Flowers surround the corpse in several photos. In others, mortality and time symbols, such as an hourglass, identify the portrait as post-mortem photography.

Real Victorian death photos provided families the impression of control by recording the deceased on film.

Despite the fact that they had lost a loved one, they were nevertheless able to design the photo to highlight a sense of serenity and tranquility. In several situations, post-mortem photos actually gave the appearance of life. Families may want cosmetics to conceal a macabre pallor. Some photographers even agreed to add open eyes to the final shot.

Fake Post-Mortem Photography

Today, numerous Victorian death images circulated online are either forgeries or photographs of the alive misidentified as the dead. Consider a widely circulated photograph of a man lying in a chair. Many subtitles suggest that “the cameraman posed a deceased person with his arm holding the head.” However, the picture in question was shot years before the actual death of the person in the image, such as with writer Lewis Carroll.

When viewing Victorian death images, Mike Zohn, proprietor of Obscura Antiques in New York, provides a helpful rule of thumb: “As easy as it seems, the great rule of thumb is if they appear alive — they’re living.”

Even though some Victorians attempted to bring portraits of the dead to life by applying paint to the cheeks, the great majority merely wanted to capture the sight of a lost loved one. While many of us now couldn’t conceive of doing anything like this, it’s apparent that it helped the Victorians cope with their loss during a period of severe conflict.

Fake postmortem images, whether mislabeled by mistake or purposely incorrectly labeled to peddle for profit, have been common on the Internet in recent years. They populate online Victorian oddities collections and gather on social media sites—even normally credible websites have helped contribute to the misconceptions.

It’s awful, but it’s also understandable: there’s certainly something captivating about a gruesome, not-so-distant society dealing with death in ways we don’t.

Many supposed postmortems are frequently considered to be of deceased persons because something “spooky” appears. Too-stiff stance, unnatural-looking eyes, or creepy shadows may easily launch a photo’s postmortem career, and most of this ostensible proof is, once again, simply evidence of outdated photographic technology. Earlier chemical processes caused colors to look differently (blue eyes might seem white), and exposure could leave limbs black in order to render a clear image of the face.

The History of Victorian Post-Mortem Photos

Portraiture became more prevalent after the development of the daguerreotype in 1839 since many people who could not afford to order a portrait painting could afford the cost to sit for a photographic session. This also gave the middle class a means to remember deceased loved ones. Previously, post-mortem portraiture was limited to the upper classes, who continued to honor the departed using this new approach.

Victorian post-mortem photography was most prevalent in the 19th century.

Because photography was a new technology at the time, it is possible that many daguerreotype post-mortem pictures, particularly of newborns and small children, were the only images ever taken of the sitters. The extended exposure duration made photographing dead subjects simple. Long exposure durations also contributed to the phenomena of hidden mother photos, in which the mother was concealed in the frame to calm and keep a tiny child immobile.

Post-mortem photography thrived in the earliest years of photography, among people who desired to capture a photograph of the departed.

Many photography firms benefited from this in the 18th century. Because of the subsequent creation of the carte de visite, which allowed many prints to be created from a sole negative, reproductions of the image could be shipped to family. As the 20th century approached, cameras became more affordable, and more individuals started to be able to take their own images.

Cultural Variations of Post-Mortem Photography

The “Last Sleep” stance, in which the corpse’s eyes are closed and they recline as though in rest, is a frequent pose of the departed. Another popular option was to portray the deceased sat in a chair or placed in a picture to simulate life, as these images would function as their last public interactions.

It was standard practice in the Victorian period to capture dead young children in the embrace of their mothers.

Some photographs, particularly ambrotypes, have a pink tinge applied to the corpse’s cheeks. Later images show the victim in a coffin, often surrounded by a big crowd of mourners. This was very popular in Europe, but less so in the United States. Photographs, particularly of those regarded to be exceedingly holy laying in coffins, are still exchanged among Orthodox Christians.

North and South America

By the mid-to-late 19th century, post-mortem photography had become an entirely private activity in the Americas, with debate shifting away from trade publications and public forums. There was a revival of mourning tableaux, in which the living were captured encircling the deceased’s coffin, occasionally with the corpse visible.

This practice was carried on into the 1960s.

Icelandic Post-Mortem Photos

In the Nordic nations, post-mortem photography was most prominent in the early 1900s, but it eventually faded out about 1940, shifting mostly to hobbyist photography for private use. When the culture of Iceland around death is examined, it is determined that the country saw death as a crucial and essential companion. The nation’s rate of infant mortality was greater than that of European nations for much of the 19th century. As a result, death became a public subject that was viewed through the religious spectacles of Icelanders.

Many people feel that Iceland’s sentiments about post-mortem photography may be derived from its prior poetic statements of above-average mortality rates.

In the early 1900s, extensive details on a person’s death could be obtained in the obituary column of a newspaper. Before cultural standards transformed the perception of death to be considerably more private and personal, this was symbolic of the community’s involvement in the death.

Photos of the departed, their coffin, or burial stone, together with documentation of the ceremony and wake, were uncommon in 1940. By 1960, there was essentially little evidence of community-based commercial post-mortem photographs in Nordic society, with just a few amateur images left for the benefit of the deceased’s family.

The origins of post-mortem photography in Iceland are unknown, however, they may be dated back to the late 19th century.

Post-mortem photography was practiced throughout Europe as well as Iceland and the Nordic nations. In Iceland, arrow speed played a minor significance, with only a few specimens going back to the Middle Ages manuscript drawings or memorial tablets from the 1700s. These cases were mostly limited to professionals rather than the general public. The style of images altered as the custom of treating and caring for the deceased passed from the duty of the family to that of the medical personnel.

Post Mortem Photos in the UK

It was traditional to depict the deceased in paintings and sketches as early as the 14th century. This began in Western Europe and swiftly expanded throughout the continent. These portraits were mostly reserved for the upper crust. Post-mortem photos became widely available with the invention of photography. In Victorian Britain, post-mortem photography was very popular.

From 1860 to 1910, these post-mortem photographs were styled similarly to American portraits, emphasizing the departed either sleeping or with the family; these pictures were frequently placed in family albums.

Because the two are so similar, the study has frequently been combined with American traditions. During the interwar period, post-mortem photography was still practiced. It is difficult to gauge the prevalence of postmortem photography. This is due in part to the fact that many cases are private inside family albums, as well as shifts in societal and cultural views around death. Existing portraits might have been disposed of or destroyed as a result of this.

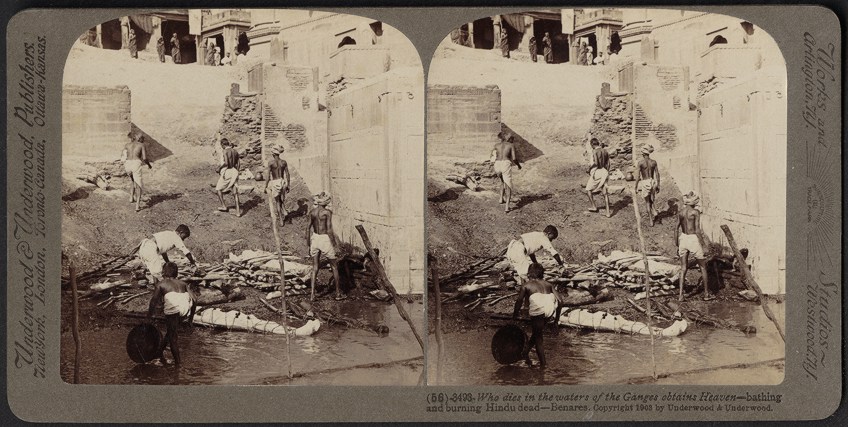

Indian Post-Mortem Photos

Individuals in India believe that if their departed loved one is burned at the funeral pyres in Varanasi, their spirit would be taken to paradise and cease the rebirth cycle. Varanasi is the sole city in India where pyres burn all day long, seven days a week, with 300 people burnt on average every day.

Death photographers visit Varanasi on a regular basis to photograph the newly departed as souvenirs for the family or as evidence of death.

As we have learned, post-mortem photography is a rather contentious topic. Although it was a common practice in the Victorian era, most people nowadays would not like the idea of owning a photo of a deceased person. However, for those that lived in that era, it was a way for them to remember those that had passed, and have a visual representation to honor their lives.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are Victorian Post-Mortem Photos?

Post-mortem photography was performed in order to get a printed photograph of your deceased family member to prominently display in your house. In the terrible case that a loved one died, taking a snapshot of their corpse or face would be regarded odd, if not frowned upon. Post-mortem photography, on the other hand, was formerly a popular habit out of respect and affection. However, throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, this unusual tradition was widely accepted as a sign of both sorrow and remembering in both European and American cultures.

What Is the Difference Between Fake and Real Victorian Death Photos?

Due to the popularity and prominence of Victorian post-mortem photos, it became a lucrative business to make and sell fake photos to the public. Cast iron posing stands were employed to assist living models to stay motionless during the lengthier exposures of the time. This helped create the illusion of stillness as it was easy to capture blurry photos on old camera equipment. They weren’t designed or built to carry the weight of a dead corpse, but they were utilized to support the limbs of persons who were still alive during a photo session.

Jordan Anthony is a film photographer, curator, and arts writer based in Cape Town, South Africa. Anthony schooled in Durban and graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts. During her studies, she explored additional electives in archaeology and psychology, while focusing on themes such as healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. She has since worked and collaborated with various professionals in the local art industry, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban (with Strauss & Co.), Turbine Art Fair (via overheard in the gallery), and the Wits Art Museum.

Anthony’s interests include subjects and themes related to philosophy, memory, and esotericism. Her personal photography archive traces her exploration of film through abstract manipulations of color, portraiture, candid photography, and urban landscapes. Her favorite art movements include Surrealism and Fluxus, as well as art produced by ancient civilizations. Anthony’s earliest encounters with art began in childhood with a book on Salvador Dalí and imagery from old recipe books, medical books, and religious literature. She also enjoys the allure of found objects, brown noise, and constellations.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Post-Mortem Photography – The Art of Real Victorian Death Photos.” Art in Context. August 11, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/post-mortem-photography/

Anthony, J. (2022, 11 August). Post-Mortem Photography – The Art of Real Victorian Death Photos. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/post-mortem-photography/

Anthony, Jordan. “Post-Mortem Photography – The Art of Real Victorian Death Photos.” Art in Context, August 11, 2022. https://artincontext.org/post-mortem-photography/.