Minoan Art – The Most Notable Minoan Artifacts, Paintings, and Art

Have you read the famous Greek myth of the Minotaur and the labyrinth on the island of Crete, ruled by King Minos? This is the island we will explore in this article, which is part of the Greek Aegean Islands. It was also home to the ancient Minoan Civilization – who created some of the most beautiful artworks that influenced the Classical era of Greece and Rome.

Brief Historical Overview: The Aegean Civilizations

The Minoans existed before the Classical art periods that we all know very well – the Greek and Roman art periods. The Greco-Roman periods are also remembered to have influenced the Renaissance artists and inspired a surge of creativity and revivification of Classical philosophical ideals of beauty and harmony.

But who inspired the Greek world and ideals?

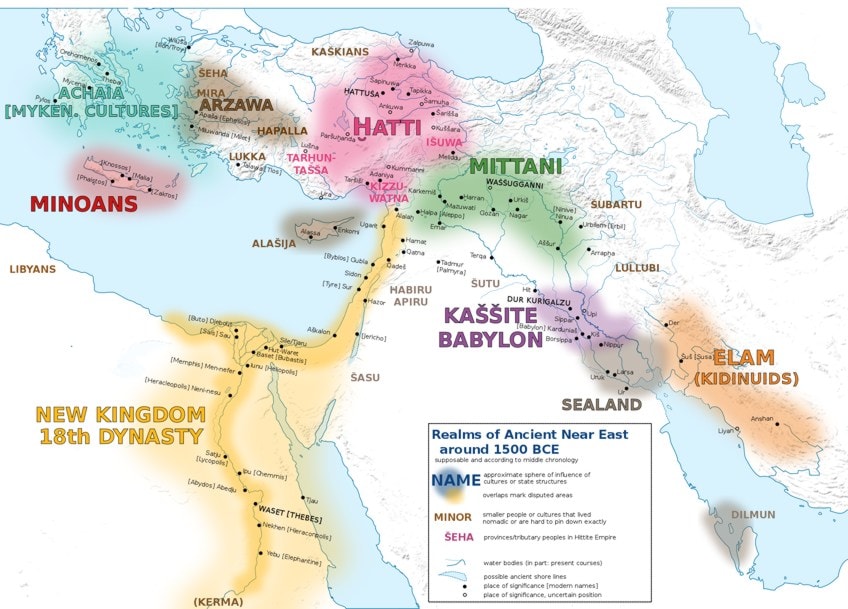

Civilizations we seemingly forget to talk about as often as the “Classics” are the ancient Aegean civilizations that almost set the foundations for the ancient Greeks. So, who were the ancient Aegean Civilizations, and where do the Minoans, the subject of our article, fit in?

Let us start with the Aegean Civilizations, which were of Greek origin and lived by the surrounding Mediterranean Aegean Sea. Three prominent cultures emerged and are known collectively as the Aegean Civilizations. These were the Minoans based in Crete, which is an island south of the Greek mainland. The Mycenaeans, who lived on Mainland Greece and eventually took over the Minoans. Thirdly, was the Cycladic civilization who occupied the Cyclades islands, located southeast from the Greek mainland.

Who Were the Minoans?

Now that we have some contextual basis of where the Minoans fit in, let us explore them further. They lived during the Bronze Age around 2000 BC to 1500 BC. Some sources also say they started earlier, around 3500 BC, but only advanced as a society around 2000 BC. The Minoans mainly lived and thrived on the Greek island of Crete with Knossos as one of the main cities, which is also known as “Europe’s oldest city”.

The name “Minoan” did not originate at the same time though.

It was given in more modern times, during the 19th century. It was named after the Greek myths of King Minos, who was associated with the famous Minotaur and the labyrinth. The myth, in as little detail as possible, goes along the lines of King Minos getting 14 children (seven girls and seven boys) from King Aegeus who are then sent to the labyrinth and eaten by the minotaur.

The German historian Karl Hoeck first introduced the term minoisch in his publication Kreta (c. 1823 to 1829). Erroneously, many believe it was the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans who first used this name. Evans discovered the great palace and city of Knossos and verified from all the evidence the lives of the Minoans, or Cretan, culture during the Bronze Age.

His contributions to the unearthing of the history of Crete, its people, and its culture were invaluable.

Palaces and Pottery: Minoan Classification Systems

Two classification systems have been used to categorize Crete’s developments as a civilization. These were based on the growing developments as evidenced by numerous palaces during different periods and the events that occurred around these. The archaeologist Nikolaos Platon started this classification, which was referred to as the Palatial Periods.

The other categorization was in accordance with the different styles of pottery that developed throughout the Bronze Age Crete. Sir Arthur Evans started this classification system and divided it into three time periods.

The three periods were named as follows: Early Minoan (EM) (c. 3000 BC to 2100 BC), Middle Minoan (MM) (c. 2100 BC to 1600 BC), and Late Minoan (LM) (c. 1600 BC to 1100 BC). Evans further subdivided the above periods into the following: Early Minoan (EM I, EM II, EM III), Middle Minoan (MM IA, MM IB, MM IIA, MM IIB, MM IIIA, MM IIIB), and the Late Minoan (LM IA, LM IB, LM II, LM IIIA, LM IIIB).

The Palatial Periods, by Platon, and their respective estimations of dates were divided into the following: Prepalatial Period (c. 3000 BC to 2000 BC), Protopalatial (Old Palace Period) (c. 1900 BC to 1700 BC), Neopalatial Period (New Palace) (c. 1730 BC to 1450 BC), and the Post-Palatial Period (c. 1450 BC to 1100 BC).

These classification systems overlap with the other in terms of dates and it is important to remember that these are also estimates of dates and time periods during the Bronze Age period. Let us explore them further and what some of their main related characteristics were.

Prepalatial Period (c. 3000 BC to 2000 BC)

The Prepalatial Period started around 3000 BC and communities lived mostly in large cities, or towns, without any known hierarchical system, but communities appeared to live around a large palace-like area. Trade with ivory, copper, tin, and gold also took place in places like Egypt, Syria, and Asia. Large tomb structures also existed. Pottery and jewelry were produced during this period.

Protopalatial (Old Palace Period) (c. 1900 BC to 1700 BC)

The Protopalatial Period, also known as Old Palace, started around 1900 BC in places like Knossos and Phaistos. Other places included Chania and Mallia, and other smaller locations. Palaces were built during this period with an authoritative figure in place, namely a king.

These palaces also suggested hierarchical systems and social class structures in place and acted as administrative systems. The layout of these palaces had open courts, storage rooms, or “spaces”, and what is referred to as “domestic” rooms.

In pottery, the Kamares style was one of the popular styles marked by a black background, or “field”, with blue, red, orange, and white motifs, which were usually floral and abstract patterns.

It is believed an earthquake destroyed most of these palaces around the 1700s BC, however, there is debate about the exact causes, some suggest it was from invasions. Regardless of the cause, most palaces needed to be rebuilt. This marked the beginning of the Neopalatial Period.

Neopalatial Period (New Palace) (c. 1730 BC to 1450 BC)

The Neopalatial Period was marked by a resurgence in the palace structure after most palaces were severely damaged during the Old Palace Period. Palaces were built with more grandeur than before and some of the grandest were in Knossos and Phaistos, but there were several others.

The Zakros palace is worth mentioning too because it was an important administrative center. It was also located by a harbor that positioned it as a center of trade.

Archaeological excavations found that there were more settlements surrounding the palaces and an increase in urban development with rooms like workshops, storage spaces, and villas. There was also evidence of paved roads that were used as links from the palaces to other towns.

This period was marked with more developments in society, including early forms of writing called Linear A. This was done on clay tablets and reportedly utilized for recording business or administrative details. Pottery also changed throughout the different periods with more decorative motifs related to marine themes.

There was also an influence from mainland Greece, the Mycenaeans, during this period. Furthermore, the period ended abruptly, and some sources state it may have been severe environmental disasters.

Post-Palatial Period (c. 1450 BC to 1100 BC)

During the Post-Palatial Period, there were new developments in the writing script used, referred to during this period as Linear B. This also had some observable forms of the Greek language. Many discoveries during this period showed similarities to the mainland Greek culture, the Mycenaeans.

For example, in the architectural structures in Chania and Knossos, which notably includes Knossos’ throne room.

This period also ended with what appeared to be burned settlement sites or abandoned by the inhabitants. Inhabitants also appeared to settle more in the mountains, namely the regions Kephala and Karphi. It is also important to note that Mycenae possibly took more control of this region and ruled various societal and economic systems.

The Importance of Knossos – “Europe’s Oldest City”

As we mentioned above, Knossos was one of the main Minoan cities discovered and is used as a “type site”. A “type site” is used as a primary model that defines a historical culture excavated in archaeological digs. Knossos would be the defining site for the Minoan archaeological discoveries.

Knossos was in fact more than a type site; it has also been one of the most visited archaeological sites within Greece and it dates around 9000 years, among others.

It is safe to say that this is an important historical site that provides a wealth of historical data about how the Minoan culture lived and produced their art, ranging from architecture, pottery, frescoes, and many other Minoan artifacts.

Firstly, it was Sir Arthur Evans who excavated Knossos, which was believed to be a palace. However, before the Palatial Period, Knossos was a Neolithic site with excavations giving evidence of farming settlements, which was estimated to be around 8000 BC.

The palace’s structural layout consisted of the courtyard, which was centrally placed and probably used for various ritualistic events. There were also numerous storage rooms in the shape of long thinned rooms, including various pits, called Kouloures, sunken in the ground, that were believed to store grains.

The “Kouloures” were covered during the New Palace Period when the palace underwent reconstruction. There were also several entrances and numerous rooms that served different purposes.

Knossos has a complex history and has been destroyed and rebuilt over the centuries. It was not only its reconstruction that left its mark but the palace was richly decorated with beautiful Minoan wall paintings, which we will explore in further detail below. This old city also stood the tests of time, from Neolithic settlements, Byzantine churches, and Classical Greek and Roman habitation in between.

Minoan Art

Minoan art can be found in a variety of modalities, ranging from Minoan sculpture, painting, pottery, and many other forms like jewelry and weapons. The subject matter also ranged from abstracted shapes, animal figural motifs, and references to the natural environment.

Below, we will take a closer look at some of the prominent characteristics of Minoan art as well as more specific examples throughout the Minoan art modalities.

Characteristics of Minoan Art

Minoan art was made for different purposes that served not only functionality but also as decorations for interiors and the elevation of political figures and their status when looked upon. Minoan wall paintings were among some of the most common types of paintings. These adorned the palace’s walls.

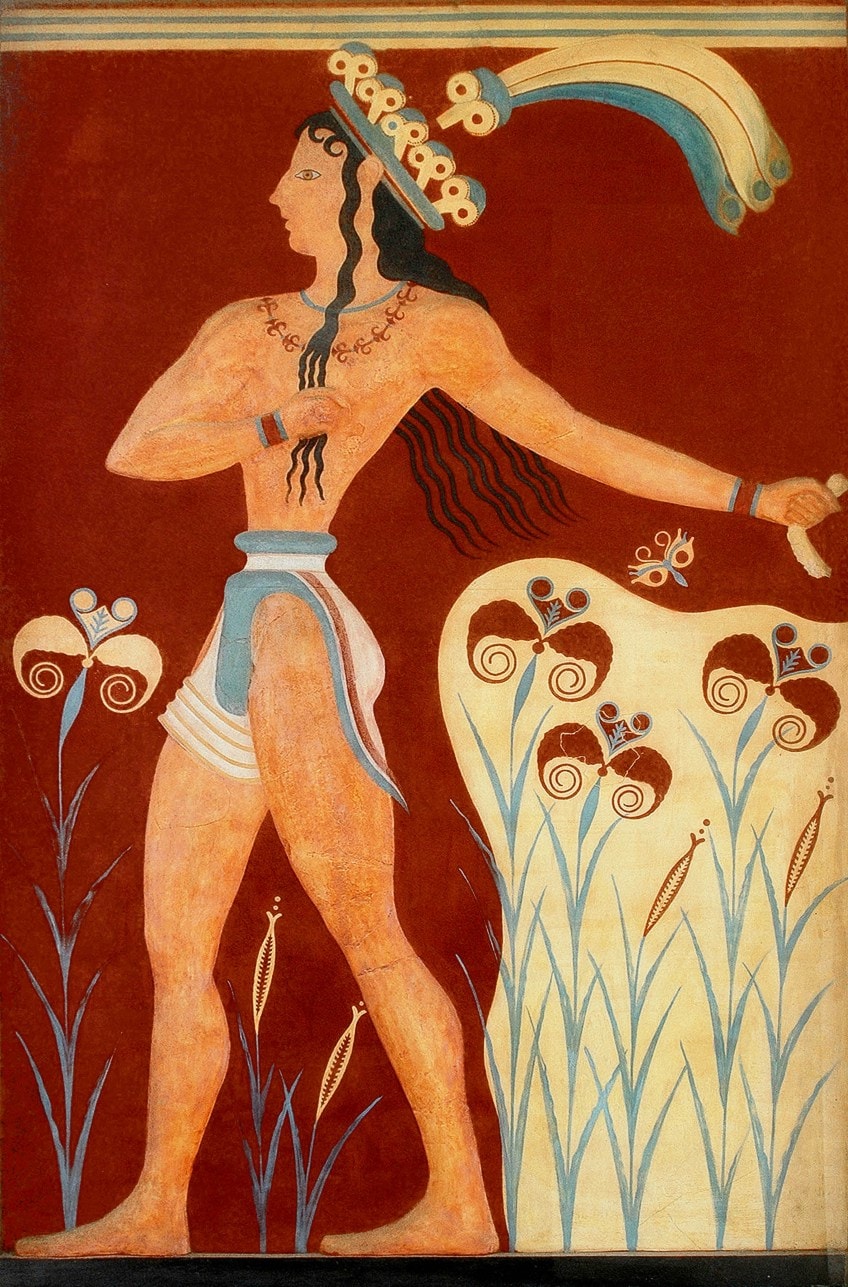

The subject matter was composed of human figures, a common theme in many of these depictions that conveyed everyday activities. We will see many compositions that are dynamic and suggest a lot of movement.

Another dominant subject matter was derived from nature, for example, animals, marine life, as well as foliage.

Another important part of the Minoan art subject matter consisted of more abstracted forms other than just depictions from nature. We will notice a lot of curvilinear shapes, lines, and other geometric forms adorning not only walls but pottery and other objects.

A common question is also sometimes asked, “How do Minoan frescoes differ from Egyptian frescoes?”. Human figures in Minoan painting are often compared to the Egyptian depictions of human figures because they also appeared in profile. The Egyptian figures appeared with their torso facing the front with their heads and legs in profile. Minoan figures were portrayed in full profile (this simply means figures are portrayed from a side view) and quite stylized, sometimes with “exaggerated” features like broader shoulders and very narrow waists.

However, there were other differences between these two cultures.

The Egyptians painted on tombs while the Minoans used their paintings to adorn walls of interior spaces. The subject matter was also different, for example, in Egyptian paintings we see dominant religious themes and more natural, everyday life, scenes in Minoan wall paintings. Human figures also appeared more rigid and “stiff” in Egyptian paintings compared to the more lively and loose figures in Minoan art.

The fresco styles in Egyptian and Minoan paintings were also different. For example, the Minoans utilized a wet fresco, also called true fresco, where the plaster is still wet. The Egyptians utilized secco, which was dry plaster.

Minoan Frescoes

Minoan painting commonly consisted of wall paintings done in the fresco technique, as mentioned above, in the true fresco technique also referred to as buon fresco. This consisted of color pigments applied onto wet plaster, typically limestone.

It is worth noting that the Minoans also utilized the “secco” technique, which was the application of paint on dry plaster.

Although a lot of the Minoan artworks have been degraded over time, there are a lot of examples of wall paintings. Numerous examples include natural scenes of animals and nature, which made up a large part of the subject matter on Minoan wall paintings.

There are two popular sites where important wall paintings were found, namely, that of Knossos and the wall paintings from Akrotiri at Thera, otherwise known as Santorini, the modern-day Greek island. Although the paintings from Thera were from a different culture than that of Crete these are viewed amongst the Minoan wall paintings too because it is believed the Minoans also settled on Thera. It is important to remember there were numerous paintings that spanned Minoan art.

Below we will look at only a few of the more popular paintings from each of the important locations excavated, namely, Knossos and Thera.

Minoan Painting Examples From Knossos

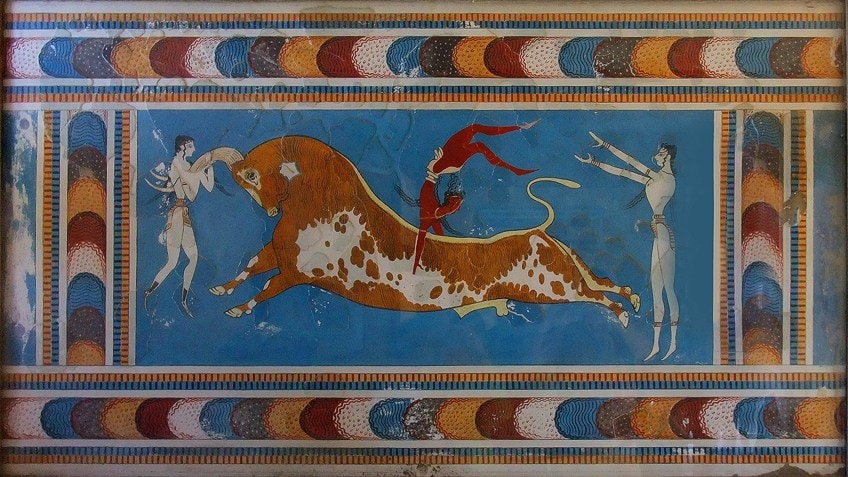

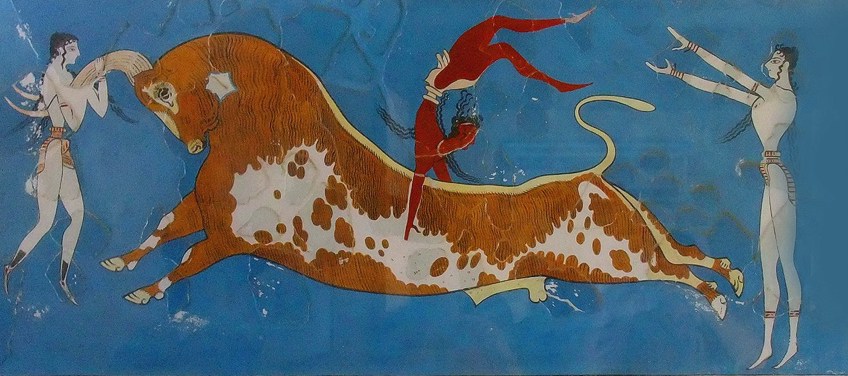

Some of the more well-known Minoan painting examples include the Griffin Fresco (c. 1450) from the Throne Room at Knossos, dating around 1700 to 1450 BC, the Dolphin Fresco (c. 1500 BC), Prince of the Lilies, Priest King (c. 1550 BC), La Parisienne (c. 1350 BC), and the Bull-Leaping Fresco (c. 1400 BC), among many others.

Let us take a closer look at the Bull-Leaping Fresco, which was discovered in the eastern side of the central court area in the area called the Court of the Stone Spout; it was along the upper walls. The restorer Émile Gilliéron assisted in the restoration process of this fresco and managed to piece it together from the existing fragments. It measures 78 centimeters in height.

What we see of the fresco now could possibly be depicting a famous sport during the Minoan period, which was bull sports. Some scholars also suggest this could have been a bull-leaping ceremony for rites of passage in adulthood. It may have taken place in the Central Court area of the palace.

We see three figures and a bull in the center of the composition. There is a figure in front of the bull, behind the bull, and in the process of jumping over the bull. The bull itself appears in the motion of leaping and charging forwards with the figure in the front holding on to the bull’s horns.

The image is suggestive of gymnastics and a seeming screenshot of a fast-paced sport in action.

The figure in front will most probably be jumping, otherwise known as vaulting, over the bull, while the figure in the middle is nearing the completion of his jump. The person behind the bull stands in the typical stance of having completed a jump, this is also referred to as “sticking the landing”, characterized by the arms held out in front.

If we look at the three figures, the two at either end are painted white and the central figure is painted brown. This is reminiscent of how Egyptians painted and color-coded the different genders. Females were portrayed in white and males in brown. However, the females are wearing loincloths, which indicate masculine dress and their hair is curly and long.

The leaping male figure is easily understood as a male if we look at it from the way Egyptians color-coded gender as well as from his loincloth. Sources suggest that gender was possibly fluid during these times and that the white-painted “females” could possibly be younger men.

The figures are also depicted with characteristic stylized features, namely the thin and narrow waists. Their thighs are also depicted larger in size compared to their other muscles, including their upper torsos, which look broad and almost stand out.

The background is monochromatic, a light blue, white color. There are no other contextual elements that place the characters into a broader storyline. We will also notice a border surrounding the fresco, appearing like rectangular curved shapes overlapping the other, each one with a pattern.

La Parisienne is another fine example of Minoan wall paintings and still retains its color. It was given the name La Parisienne by Edmond Pottier, an ancient Greek art historian, who thought she resembled a modern woman from Paris. The wall painting was discovered by Sir Arthur Evans.

What we see from La Parisienne is her head and upper torso area, the only part of the fresco that has been preserved. She has black curly hair; one curl hangs down the front of her forehead. Her eyes are depicted as quite large oval shapes and her lips are donned with a deep red color.

She is wearing what is referred to as a “sacred knot”, this is a piece of cloth tied to a loop at the back or the nape. This cloth hangs down the back. She is wearing a dress with red and blue stripes. There is a thicker, circular, band running along the rim of her dress.

Her skin is white, which is reminiscent of the way Egyptians portrayed gender and the Minoans did it similarly. This also points us to the Egyptian influence on the Minoans. The two cultures also traded with each other.

La Parisienne was found as a fragment that reportedly fell from what is known as the Camp Stool Fresco on an upper story in the Knossos Palace’s west wing. The fresco consisted of two registers, or panels, with various male and female figures sitting on stools holding cups for the others, possibly servants, standing to pour from the jugs in their hands.

La Parisienne was probably part of this fresco as one of the women sitting on a stool. Most of the other women are sitting in full profile, and we can surmise then that she is also sitting in full profile. This fresco was also probably in an area where feasts or banquets took place. She was also believed to possibly be a priestess.

Minoan Painting Examples From Thera (Santorini)

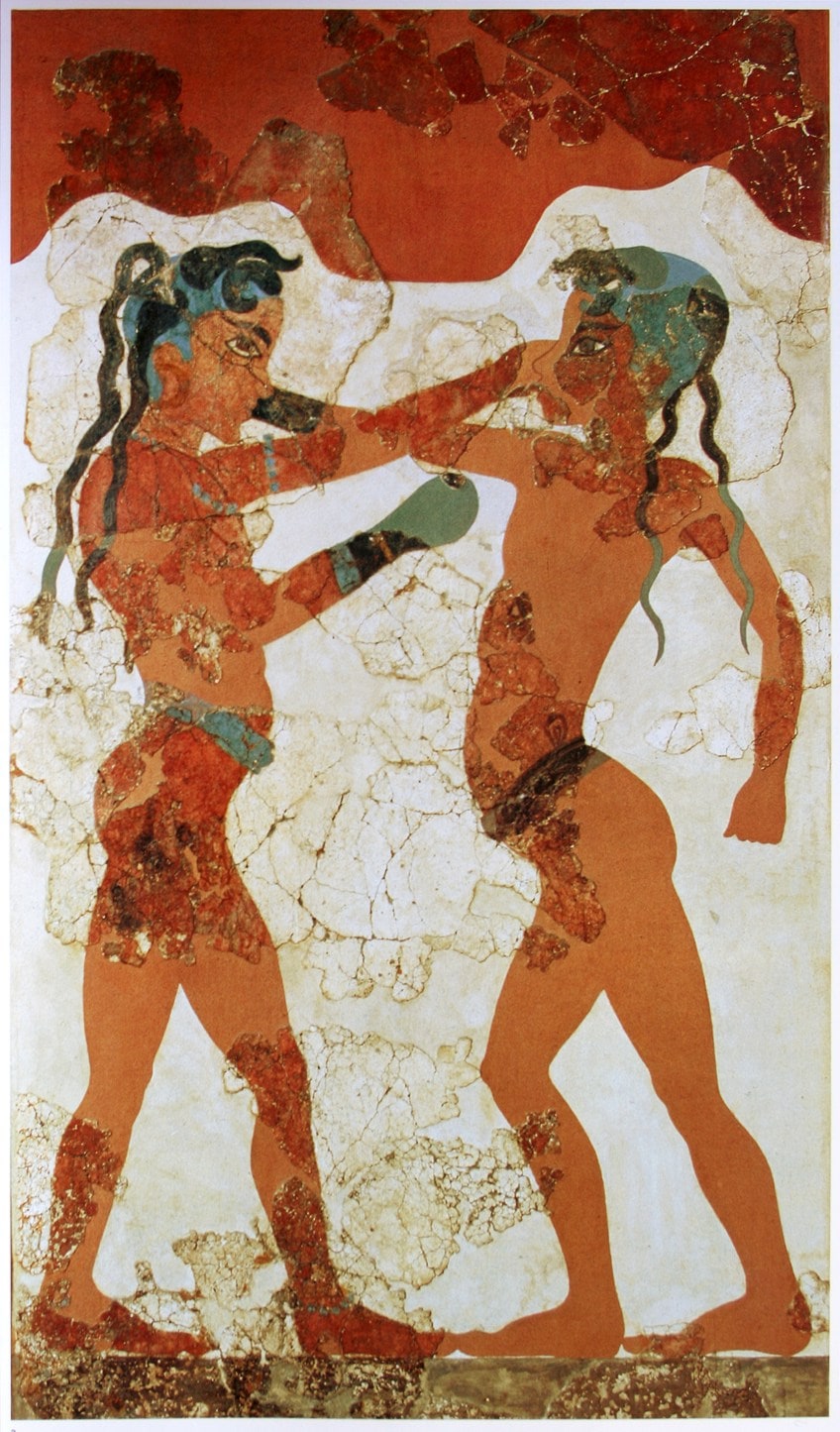

There were numerous frescoes discovered from Thera, some include, Flotilla or Akrotiri Ship Procession (c. 2000 to 1500 BC), the Blue Monkeys fresco (c. 1600s BC), one of the popular and landscape frescoes, the Landscape with Sparrows, or Spring Fresco (c. 1650 BC), and the Akrotiri Boxers fresco (c. 1700 BC).

In the Landscape with Sparrows, or Spring Fresco, we see the walls covered with what appears to be several mountainous regions or hills with lilies growing on them and on top of them. There are white, red, and blue colored sparrows seen flying not too far above the lilies. The landscape is beautiful in its rendering and the lilies appear to be moving gently with what is undoubtedly a breeze.

In the Akrotiri Boxers fresco, we see two young boys (or girls?) engaged in a boxing match with one another. It was discovered in what is called Building Beta, Room B1. What may suggest they are male is their darker, brown, skin color. Both boys have long hair hanging in thickened strands past their shoulders. The boy to our left appears to wear jewelry and the boy to our right only wears a belt, both are mostly in the nude.

The subject matter of this fresco points to another example of different sports played by the younger generation of the time, boxing being one of them and bull-leaping the other, as noted in the Bull-Leaping Fresco mentioned above.

This could either be a sparring match or a real-life boxing match.

Minoan Pottery

Minoan pottery was also beautifully decorated with different floral motifs, geometric patterns, animals, flowers, fish, birds, to name a few. There were also neutral and earthy color schemes, for example, whites, browns, blacks, reds, and blues.

Throughout the different time periods, the styles of vase painting changed too and were named accordingly.

During the Early Minoan Period, there was Incised ware, which had patterns of lines running parallel with the other. These were incised, as the name suggests, into the clay. These appeared with rounded bottoms in dark burnishes. Some items included jugs, jars, and cups.

Other types of pottery styles during the Early Minoan period were the Agios Onouphrios Ware, which had a lighter background with darker patterns of parallel lines. The patterns were drawn with a clay slip in iron red. This would turn red when exposed to oxidizing effects from fire and black when there would be more smoke present. The types of wares were cups with two handles, bowls, and jugs.

Vasiliki Ware was another common style, discovered and named after the village Vasiliki in Crete. These were characterized by what is described as the “mottled” patterns. The shapes were referred to as “teapots” because of their longer spouts and smaller, circular, mouth openings.

Some examples include the Vasiliki ware jug (2400 BC to 2200 BC) that almost appears as if it is a bird with its beak facing towards the sky. Then there is the Teapot in the white style (c. 2300 to 2000 BC), which almost appears like a Toucan bird with its long and square-like protruding spout.

The potter’s wheel was introduced during the Middle Minoan Period, which led to new developments in the production of pottery. One of the styles included the Kamares Wares, named after the Kamares cave, which was found in 1864. Numerous Minoan artifacts were found here including pottery.

Kamares pottery is characterized as “light-on-dark”, lighter patterns often floral and abstract, on a dark background.

The background was usually black with the application of whites, oranges, and reds. These wares were made on the potter’s wheel and became quite thinly constructed; these were referred to as “eggshell” wares.

An example is the Kamares Ware Jug (c. 2000 BC to 1900 BC), discovered at Phaistos, which was another Minoan palace located toward the south-central side of Crete. It stands 27 centimeters tall and has a characteristic black background with red and white patterns. The patterns are geometric shapes and spirals.

However, upon closer inspection, we will notice this jug appears almost like a bird with its beak facing the sky. The jug has been described as zoomorphic in shape and the handle doubles as a feather reaching from its head. The geometric shapes on the bulbous body almost become like beautiful plumy patterns, forming part of the bird.

During the Late Minoan Period, the Floral Style and Marine Style were dominant.

The Floral Style focused on floral and leafy patterns. It was the Marine Style, however, that caught almost everyone’s attention due to its marine-inspired motifs. Vessels had all sorts of marine animals painted on them, from fish, dolphins, octopuses, to name a few. The background was also usually suggestive of the ocean.

The Marine Style used a dark-on-light technique, where the background was lighter, and the subject matter was painted darker. A famous example is the Octopus Vase (c. 1500 BC) from Palaikastro in Crete. It has a large, rounded body with a small neck and opening with two small handles attached to the neck.

Painted on the vase is a large octopus, its head is in the center with two large eyes gazing at us. Its tentacles are wrapped around the whole vase, which makes it part of the vase. It is almost as if the vase was also made to accommodate the shape of the octopus and bring to life the extending tentacles. Between these tentacles are pieces of seaweed.

Minoan Sculpture

Minoan sculpture is known to be rare, however, there have been some prominent pieces found. From earlier periods figurines were made from clay and later made from bronze, gold, ivory, and faience. Some figurines were of humans and others were of animals. The women figurines were depicted wearing long skirts with what appeared to be several layers and men were depicted with loincloths. An example is a Minoan Woman (c. 1600 BC to 1500 BC) cast in bronze.

Another famous example, among others, is the Snake Goddess (c. 1600 BC), which was excavated by Sir Arthur Evans at the Palace of Knossos. She stands 29.5 centimeters tall wearing the characteristic layered skirt; there are seven layers also known as flounced layers. Around her thin waist, there is an apron that just covers the top layer of the skirt attached by a thick band with vertical stripes around it. She wears a top that exposes her breasts. This female figure is holding up two snakes in both hands and on top of her head is a sitting cat. Her facial features are quite defined, we notice her eyes stare right at us.

There is wide scholarly debate about who this woman may have been during the Minoan period. A typical answer could be that she was a priestess or a symbol of fertility.

Another example of a Minoan sculpture is the bronze Bull Leaper (c. 1550 BC to 1450 BC). It depicts a human figure in the process of leaping over a bull while the bull is simultaneously leaping in mid-air. This is another example of the wide variety of depictions focused on sports like bull-leaping and the acrobatics involved in it.

The Palaikastro Kouros (c. 1480 BC to 1425 BC) stands around 50 centimeters tall and is one of the largest sculptures, of what appears to be a younger male figure, excavated from the Late Minoan Period. It was made from rock crystal, gold, serpentine, and ivory. It was reconstructed from its fragmented pieces.

There are elements that are not as anatomically correct or realistic, but this is another characteristic of the Minoan style. For example, the thumbs are longer than what is usual and reach over the fingers’ knuckles, and there are veins on his feet that do not correspond with real veins.

Regardless of anatomical inaccuracies, this figure has been built with a keen eye for anatomical detail and from what we can see from him he has an athletic build, suggested by how his muscles have been molded. He stands with one leg in front of the other, his knees are locked, both his arms are up by his chest, and his hands are made into two fists. It is almost as if he is in a jogger’s pose.

What is also interesting about Palaikastro Kouros is his ties to Egypt. The materials he is made from, gold and ivory, originated from Egypt, suggesting trade between the two cultures. However, the pose of one foot forward is also reminiscent of the Egyptian pose. His proportions are likened to those of the Egyptian canon for bodily proportions.

The figure also appeared to have been covered with gold, which is considered one of the earliest, and possibly first, known statues of this type.

This is referred to as chryselephantine, which is when statues are given an overlay of ivory and gold. This statue also reminds us of the Kouros statues from the Archaic Greek Period and was possibly the forerunner to these.

An Undying Culture

During the Minoan’s later years, they were conquered by the Mycenaeans. However, there is also debate that a large-scale eruption caused most of the damage to the Minoans and left them vulnerable to attack. The Mycenaeans ruled during the later Bronze Age, from around 1600 BC.

The Minoans left behind a wealth of artifacts giving us clues and information about how they lived and produced art. The artworks ranged from not only their palatial architecture, but their magnificently decorated pottery, jewelry, weapons, and many other objects. What we discussed in this article is just the tip of the iceberg of the elegance and sophistication imbued in a culture that will live on forever.

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was the Minoan Period?

The Minoans lived during the Bronze Age around 2000 BC to 1500 BC. Some sources also say they started earlier, around 3500 BC, but only advanced as a society around 2000 BC. The Minoans mainly lived on the Greek island of Crete.

Where Does the Minoan Name Come From?

The name “Minoan” did not originate at the same time though, it was given in more modern times, during the 19th century. It was named after the Greek myths of King Minos, who was associated with the famous Minotaur and the labyrinth. The German historian Karl Hoeck first introduced the term minoisch in his publication Kreta (c. 1823 to 1829). The archaeologist, Sir Arthur Evans, borrowed and formalized the use of this name.

How Do Minoan Frescoes Differ From Egyptian Frescoes?

The Egyptian figures appeared with their torso facing the front with their heads and legs in profile. Minoan figures were portrayed in full profile and stylized with “exaggerated” features like broader shoulders and very narrow waists. The Egyptians painted on tombs while the Minoans used their paintings to adorn walls of interior spaces. Subject matter in Egyptian paintings was religious and more natural and every day in Minoan wall paintings. Human figures also appeared more rigid and “stiff” in Egyptian paintings and more natural and loose in Minoan art. Minoans utilized a wet fresco technique and the Egyptians utilized secco, which was dry plaster.

What Are the Minoan Classification Systems?

There are two main classification systems to categorize Crete’s developments as a civilization, namely the Palatial Periods and the pottery styles. The Palatial Periods are divided into the following: Prepalatial Period (c. 3000 BC to 2000 BC), Protopalatial (Old Palace Period) (c. 1900 BC to 1700 BC), Neopalatial Period (New Palace) (c. 1730 BC to 1450 BC), and the Post-Palatial Period (c. 1450 BC to 1100 BC). The other categorization was in accordance with the different styles of pottery that developed throughout the Bronze Age Crete, these were namely, Early Minoan (EM) (c. 3000 BC to 2100 BC), Middle Minoan (MM) (c. 2100 BC to 1600 BC), and Late Minoan (LM) (c. 1600 BC to 1100 BC).

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Minoan Art – The Most Notable Minoan Artifacts, Paintings, and Art.” Art in Context. December 14, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/minoan-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 14 December). Minoan Art – The Most Notable Minoan Artifacts, Paintings, and Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/minoan-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Minoan Art – The Most Notable Minoan Artifacts, Paintings, and Art.” Art in Context, December 14, 2021. https://artincontext.org/minoan-art/.