Mezquita de Córdoba – Spain’s Cathedral in a Mosque

Suppose you have never heard of the Great Mosque of Córdoba. In that case, you might have several questions, for example: who built the Mezquita de Córdoba, where is la Mezquita de Córdoba situated, what is the floor made of inside Mezquita de Córdoba, and is there really a cathedral inside a mosque in Córdoba in Spain? Although today it is the official cathedral of Córdoba’s Roman Catholic Diocese, it was once one of the greatest mosques in Andalusian Spain. There are also theories that the Great Mosque of Córdoba was built upon the site of an even older Visigoth church, although this theory is still debated.

Table of Contents

The Mezquita de Córdoba (c. 785 AD) – Córdoba, Spain

| Architect | Hernán Ruiz the Younger (1514 – 1569) |

| Date Completed | c. 785 AD |

| Function | Cathedral, mosque |

| Location | Córdoba, Spain |

The majesty of Córdoba’s grand mosque, with its quiet and expansive interior, cannot be overstated. The Mezquita de Córdoba, one of the most remarkable feats of Islamic architecture, alludes to a cultured age when Jews, Muslims, and Christians lived alongside each other and enhanced their city with a rich and varied mix of dynamic cultures. Throughout its history, the building has been used as both a mosque and a cathedral, and there were even claims in the mid-1550s that the site initially housed a Roman temple, but this has since been disproved.

Visigoth Church

Another popular theory is that the site initially housed a church that, following the Umayyad conquest of the Visigoth Kingdom, was divided between the Muslims and Christians for shared use. It is believed that the basilica expanded bit by bit as the Muslim community started to grow in numbers and the existing prayer space became too small to accommodate them.

The structure continued to be shared by both religions until around 785 AD when Abd al-Rahman I bought the half used by the Christians and tore it down to make space for the building of the new Great Mosque of Córdoba.

As part of the sales agreement, Abd al-Rahman allowed the Christians to reconstruct the churches devoted to their various saints. The accuracy of this theory has been called into question since archaeological information is scarce and the account is not supported by contemporaneous reports of events after Abd al-Rahman I’s initial arrival.

Construction of the Mezquita de Córdoba

It took only a year to build the Great Mosque of Córdoba. This fast building time may have been facilitated by the utilization of existing Visigothic and Roman building materials in the region, particularly capitals and columns. The design of the structure has Visigothic, Syrian, and Roman elements, but the architect is unknown. Local Iberians and Syrians were most likely among the artisans who worked on the project.

Traditional and historical documented sources claim that Abd ar-Rahman was extensively involved in the construction, however, the degree of influence that he personally had on the mosque’s architecture is debatable.

Because the Córdoba Mosque was erected on a sloping location, a substantial quantity of fill would have been required to create a level foundation.

The most notable advancement of the original mosque, which was retained and replicated in all later Muslim-era additions, was its series of double-tiered arches.

Many theories have been presented on the inspiration behind this specific feature, including the claimed resemblance of the arches to a forest of palm trees from Rahman’s childhood in Syria; nevertheless, a more practical intention may have been that the accessible columns repurposed from preceding building structures were not large enough on their own to elevate the ceiling to the required height.

The Córdoba Mosque’s courtyard has been landscaped with trees since at least 808 AD. Although the tree type is unknown, the fact that they were fruit trees is corroborated by Ibn Sahl, who was questioned to determine whether such a garden was prohibited and, if not, whether it would have been permissible to eat from it. The presence of the trees in the courtyard is confirmed by two of the city’s seals, one from 1262 and the other from 1445, each of which depicts the mosque with towering palm palms within its walls.

This courtyard is the world’s oldest continually maintained Islamic garden, with reliable documentation of its early antiquity.

Renovations and Modifications of the Córdoba Mosque

After the construction of the mosque on the site of what was previously the Visigoth Church, the structure underwent many phases of modification and renovation. This was necessary due to several invading forces that plundered and destroyed the structure. There has have been many modifications and renovations throughout the centuries, from the 11th century all the way through to the present era.

11th and 12th Centuries: The Mezquita de Córdoba

No additional modifications to the mosque were added after the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate at the start of the 11th century. Furthermore, the demise of the caliphate had direct devastating implications for the mosque, which was plundered and destroyed during the civil war that followed.

Córdoba experienced a collapse as well, but it stayed a significant cultural center.

Under Almoravid’s dominance, the craftsman studios of Córdoba were ordered to construct new finely carved minbars for Morocco’s most prominent mosques. Some of the finest Cordoban-made minbars date from this period, like the exquisite example created for the Kutubiyya Mosque that still survives.

In 1146, King Alfonso Vll of Léon briefly seized Córdoba. The archbishop of Toledo led a ceremony within the mosque to “sanctify” the structure, joined by the emperor. According to Muslim accounts, the Christians ransacked the mosque before fleeing the city, stealing its chandeliers, the silver and gold finial of the tower, and sections of the expensive minbar.

The mosque had lost practically all of its precious furnishings as a consequence of both this looting and the previous plundering during the civil conflict.

Following a prolonged phase of decline and many invasions, the Almohad caliph ordered that Córdoba be rebuilt to become his seat in 1162. His two sons instructed that the new capital and its structures be repaired as part of this preparedness. This restoration effort was overseen by the architect Ahmad ibn Baso. It is unknown which structures he renovated, but the Great Mosque is nearly certainly one of them. The mosque’s minbar was most likely renovated in the same period, as it was known to have existed until the 16th century.

13th to 15th Centuries: Conversion of the Mezquita de Córdoba

As part of the Reconquista, King Ferdinand III of Castile took Córdoba in 1236. The Córdoba Mosque was turned into a Catholic church dedicated to the Virgin Mary when the region was conquered.

According to Jiménez de Rada, Ferdinand III also performed the symbolic gesture of delivering to de Compostela the old cathedral bells stolen by Al-Mansur.

Despite being converted into a Christian church, the structure’s early Christian history experienced very minor structural changes, largely restricted to the insertion of smaller chapels and new tombs. Even the minbar appears to have been maintained in its original storage room, but it is uncertain if it was utilized at the time.

Interestingly, the employees in charge of the upkeep of the cathedral mosque during its early years were local Muslims. The church retained several of them as staff, but the majority of them worked just to fulfill a labor tax on Muslim artisans that compelled them to spend two days of the year working on the building. Over the decades, several chapels were added around the interior periphery of the structure, many of which were burial chapels built under private funding. The Royal Chapel was the first important addition to the cathedral under Christian patronage.

A more major modification was made to the Villaviciosa Chapel in the late 15th century when a new nave in Gothic style was erected by eliminating part of the mosque’s arches on the eastern side of the chapel and installing Gothic vaults and arches.

16th to 17th Centuries: Significant Modifications

The most dramatic change, however, began in 1523 with the construction of a Renaissance cathedral nave and transept in the center of the massive mosque complex. The initiative, proposed by Bishop Alonso de Manrique, was fiercely contested by Córdoba’s municipal government. The cathedral chapter finally won its dispute by petitioning King Charles V, who approved the building.

When Charles V subsequently viewed the final result, he is said to have been disappointed, saying, “You have created something anyone else could have erected elsewhere; and in order to do so, you have demolished a structure that was unique to the world.”

Hernan Ruiz I, the architect, was assigned with designing the new transept and nave. He erected the choir walls as well as the gothic vaults before his passing in 1547. He also started working on the mosque’s eastern part, where he added gothic vaults to the mosque naves. After his passing, his son took up the job. He was in charge of constructing the transepts and the buttresses that supported the building.

A powerful storm damaged the previous minaret, which was utilized as a bell tower, in 1589, and it was agreed to repair and fortify the tower.

Hernán Ruiz III’s concept was chosen, which encased the existing minaret framework in a new Renaissance-styled bell tower.

The new addition resulted in the demolition of some of the minaret’s uppermost sections. Building started in 1593 but was finally halted due to resources being diverted to the parallel development of the new cathedral transept and nave. Yet another storm caused damage to the tower in 1727 and the Lisbon Earthquake in 1755 ruined parts of it.

Baltasar Dreveton, a French architect, was tasked with preserving and repairing the tower during an eight-year period.

19th to 21st Centuries: Restorations

The ancient mihrab of the mosque was discovered in 1816, hidden behind the old altar. Patricio Furriel was in charge of rebuilding the mihrab’s Islamic mosaics, including the missing sections. Additional conservation work on the old mosque was completed between 1879 and 1923 under the supervision of Velázquez Bosco.

During this time, the cathedral-mosque building was designated a National Monument in 1882.

Félix Hernández conducted further archaeological excavations on the site between 1931 and 1936. Recent historians have noticed that modern renovations during the 19th century have partially concentrated on “re-Islamicizing” elements of the structure. This occurred within the framework of broader conservation efforts in Spain, which began in the 19th century with the research and restoration of Islamic-era monuments.

In 1984, the site was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and in 1994, the designation was expanded to include the whole historic center of Córdoba.

The bell tower repair project started in 1991 and was completed in 2014, while the Renaissance cathedral’s choir and transept were also renovated between 2006 and 2009. Up until the late 2010s, renovations of features such as chapels and several of the exterior gates were ongoing.

Architecture of the Mezquita de Córdoba

The structure has an area of 180 m 130 m after all of its historical extensions. The original floor design of the structure is based on the typical shape of some of the oldest mosques established from the start of Islam. Some of its elements were inspired by the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, which was a significant structure erected before the mosque. The Mezquita’s architectural significance stems from the fact that it was a structurally groundbreaking building for its time.

Earlier large Islamic structures emphasized verticality, but the Mezquita was designed as a horizontal and simple area, where the soul might travel freely and readily converse with God – a type of magnificent refinement of the original plain Islamic prayer space. On a floor of dense, red-slaked lime and sand, men worshipped side by side.

The Hypostyle Hall

The hypostyle hall of the structure was part of the original mosque building and functioned as the principal prayer place for Muslims. The mosque’s main hall was utilized for a multitude of functions. It functioned as a centralized prayer space for personal meditation, the five regular Muslim prayers, and the special Friday devotions with a sermon. During the reign of Abd al-Rahman I and his heirs, it would also have acted as a forum for the instruction of Sharia law.

All of the capitals and columns of the early mosque were repurposed from previous Visigoth and Roman structures, but future additions saw the inclusion of new Moorish-made capitals based on earlier Roman designs. The old flat ceiling of the mosque was constructed of wooden beams and planks with carved and painted embellishments.

Preserved remnants of the old ceiling, some of which are currently on exhibit in the Courtyard of the Oranges, were unearthed in the 19th century and have enabled contemporary conservators to recreate the ceilings of several of the mosque’s west parts in their original design.

The Courtyard

Up until the 11th century, the Córdoba Mosque’s courtyard was unpaved ground with palm and citrus trees that were watered by rainwater cisterns and then by an aqueduct. The excavated trees were placed in a specific design, with surface irrigation canals. The stone channels that may be seen now are not the originals. It contained water basins or fountains, as do most mosque courtyards, to assist Muslims in performing ceremonial rituals before prayer.

The arches that denoted the passage from the courtyard to the body of the prayer hall were initially open, allowing sunlight to enter, but most of these arches were sealed up throughout the Christian period as chapels were added along the hall’s northern side.

The courtyard of the original mosque had no adjoining portico or gallery, but it is thought that one was constructed by Abd ar-Rahman III.

The Bell Tower

In the mid-10th century, Abd al-Rahman III erected the mosque’s first minaret. The minaret has since vanished after being partially dismantled and housed in the Renaissance bell tower that may still be seen today. The original design of the minaret, though, was rebuilt by modern Spanish historian Félix Hernández Giménez using archeological data, historical documents, and depictions. It, like other North African and Andulasi minarets following it, was made out of a central shaft and a lesser secondary tower that capped it.

The lantern tower was capped with a pinnacle in the form of a metal rod with two gilded spheres and one silver sphere diminishing in size as they ascend.

The main tower has two stairs that were created for the tower’s independent ascension and descent. Three windows were positioned next to each other on two of the tower’s facades, while the panes on the other two building facades were organized in two sets. On the tier above, these windows were replicated. A series of nine windows of similar design and ornamentation continued above them, slightly below the peak of the principal shaft on each facade.

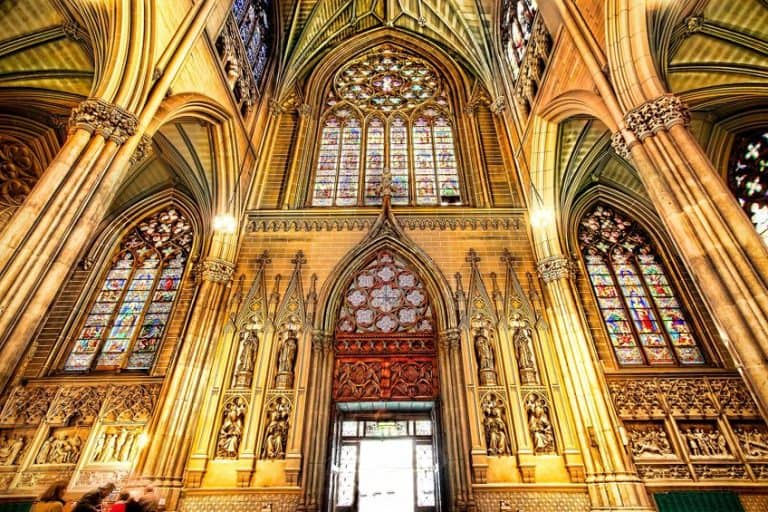

The Main Chapel

The main chapel of the cathedral is positioned at the cruciform transept and nave at the heart of the structure. This cruciform portion was started in 1523 and completed in 1607. This cruciform part has an unusual combination of styles as a byproduct of the extended time and succession of architects. The first two architects included Gothic aspects into the design, as seen in the intricate tracery pattern of the stone arches above the altar. Juan de Ochoa completed the project in a more Mannerist style popular in that period, with a dome over the vaulted ceiling.

The ensemble’s style and ornamentation incorporate a lot of symbolism. The Gothic-style ceiling above the main altar is decorated with figures of saints, musical angels, and apostles, as well as a portrait of Emperor Charles V with Mary in the middle. The numerous texts scattered amid the imagery create a long hymn to Mary. The crossing’s elliptical dome is supported by four pendentives carved with depictions of the four evangelists.

Alonso Matas designed the altar in the Mannerist style, which was completed in 1618. Juan de Aranda Salazar took over the work in 1627, and the altar was completed in 1653.

The sculpture was created by Pedro Freile de Guevara and Sebastián Vidal. Cristóbal Vela Cobo painted the original altar frescoes, which were replaced in 1715 by the present works of art by Antonio Palomino. The uppermost panels are flanked by statues of St. Peter and St. Paul, with a sculpture of God the Father above the middle section.

Pedro Duque Cornejo designed and built the choir seats across from the altar between 1748 and 1757. The ensemble was made primarily of mahogany wood and was intricately embellished with carvings, including a sequence of iconographic images. On the western edge of the ensemble, a massive bishop throne, built in 1752, mimics the style of an altarpiece.

The lower half of the throne includes three seats, but the upper part is the most striking, with a life-size portrayal of Jesus’ Ascension.

The Great Mosque of Córdoba is the most important landmark in the Western Islamic world, as well as one of the most magnificent in the world. It appears that the current location of the iconic mosque was once dedicated to the worship of many divinities, and the mosque currently houses a cathedral. The development of the Great Mosque of Córdoba includes the emergence of the “Omeya” style in Spain, as well as other forms such as Renaissance, Gothic, and Baroque architecture. Throughout its history, it has been an important place of worship for both Muslims and Christians.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Is La Mezquita de Córdoba Situated?

This famous old mosque is located in Córdoba in Spain. It is believed that the site initially housed a Visigoth place of worship. It is also thought that the structure was divided at one point so that both Muslims and Christians were able to practice their religions in it. However, it was then fully purchased and converted into a mosque. It would later be converted into a cathedral.

Who Built the Mezquita de Córdoba?

It is not known which architect built the original mosque. We do, however, know that it only took around a year to complete the structure. This was because many of the materials used were from other surrounding structures that had been repurposed, such as various columns and pillars.

What Is the Floor Made of Inside the Mezquita de Córdoba?

The original floor was built with a thick layer of mortar over compacted earth, and the walls are formed of limestone ashlars bonded together using a header and stretcher bond method. The initial floor layout was influenced by Damascus mosques and was built in the basilica form. Although there are small fragments that remain of the structures that existed on the site before the mosque was built, it is unknown what the floors of these previous structures were made from.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Mezquita de Córdoba – Spain’s Cathedral in a Mosque.” Art in Context. January 17, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/mezquita-de-cordoba/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 17 January). Mezquita de Córdoba – Spain’s Cathedral in a Mosque. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/mezquita-de-cordoba/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Mezquita de Córdoba – Spain’s Cathedral in a Mosque.” Art in Context, January 17, 2023. https://artincontext.org/mezquita-de-cordoba/.