MetLife Building – The Controversial International Style Masterpiece

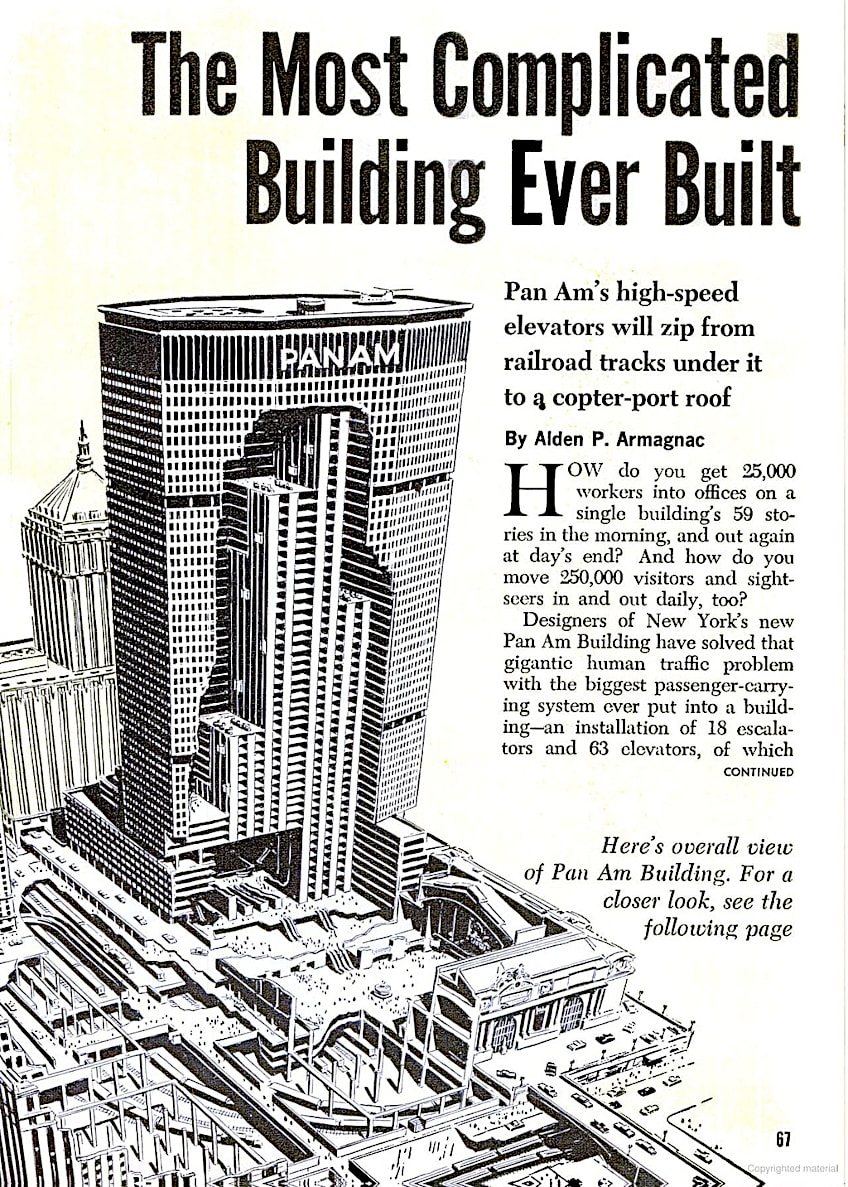

Located in the Midtown Manhattan district, North of Grand Central Terminal we find the skyscraper known as the MetLife Building, also referred to as the Pan Am building. The MetLife Building in New York, which comprises 59 stories and stands 246 meters tall, was created in the International style by Walter Gropius, Richard Roth, and Pietro Belluschi. At the time of its opening, it was billed as the world’s biggest corporate office facility by square footage. The MetLife Tower is still one of the top 100 highest structures in the United States as of November 2022.

The MetLife Building in New York

| Date Completed | 1963 |

| Architect/s | Pietro Belluschi (1899 – 1994) Walter Gropius (1883 – 1969) |

| Function | Commercial offices |

| Location | 200 Park Avenue, Manhattan, New York, USA |

The MetLife Building in New York is an extended octagonal massing, with the greater axis parallel to Park Avenue. The structure is built over two levels of railroad lines that run into Grand Central Terminal. The MetLife Tower’s facade is one of the earliest precast concrete outside walls of any New York City skyscraper. A pedestrian walkway to Grand Central’s Main Concourse, a lobby featuring artworks, and a parking garage at the tower’s base are all located in the lobby. The rooftop also housed a heliport, which was temporarily operational in the 1960s and 1970s.

The MetLife Tower’s architecture has been heavily criticized since its inception, owing partly to its proximity to Grand Central Terminal.

Original Proposal

Proposals for a tower to substitute Grand Central Station were made in 1954 to raise funds for the financially troubled railways that managed the terminal. Following that, plans were unveiled for the MetLife Tower, which would be erected behind the terminal instead of replacing it. The project, dubbed “Grand Central City” at the time, began in 1959, and the structure was formally inaugurated on the 7th of March, 1963. The skyscraper was named after Pan American World Airways, whose headquarters it housed at the time.

The MetLife Tower’s Architecture

The MetLife building’s height has been measured at 246 meters and it contains 59 stories in total. The northern and southern facades are split into three large sections each, while the western and eastern facades are each separated into one section. The 1961 Zoning Resolution, a major revision to New York City zoning regulations announced just before construction began, may have affected the building’s shape.

Facade

The first two levels and mezzanines feature glass windows and are coated in aluminum, granite, marble, and stainless steel. The structure is made up of around 9,000 precast light-tan concrete Mo-Sai panels. To provide texture to the facade, each panel is covered with a quartz aggregate. Vertical concrete mullions protrude from the exterior, dividing each story’s panels. The windows between stories are separated by flat concrete spandrels.

Though Walter Gropius thought a precast concrete exterior would be more substantial than a glass curtain wall, it merely added weight to the structure.

Additionally, the look of concrete deteriorated over time; this impact was visible in buildings like the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum but was more obvious on the facade of 200 Park Avenue. The maker of the Mo-Sai panels filed bankruptcy during the tower’s construction, requiring Diesel Construction to purchase that firm to avoid delays.

The MetLife Building’s Structural Features

MetLife Tower was erected over two subterranean levels of railroad lines that go straight into Grand Central Terminal. The tower’s substructure is supported by columns that extend through the track levels and drop below road level into the subsurface bedrock.

Around 99 columns were custom-built for the building; these columns were positioned within a few inches of preexisting steel rails but had to be separated from the other steel. Approximately 200 preexisting columns that supported the site’s previous baggage facility were strengthened

The project entailed spanning the tops of several existing columns and adding horizontal shafts weighing up to 36 tons. The superstructure was built in the same manner as bridge spans. Builders employed a procedure known as composite action to make the floor slabs, in which concrete was fused with structural steel plates to provide a stronger framework. Steel panels were used instead of concrete flooring because they were lightweight and could be built under adverse weather conditions.

The MetLife Tower’s Interior

A centralized telephone center was established to service the tower’s 30,000 telephones. The $11 million system was the first of its type in an office complex in the United States. New York Telephone’s central office reduced the requirement for leaseholders to have separate telephone desks and equipment. The telephone cables were run through the train tunnel’s roof to prevent interference with the subsurface railroad lines. The floor plates on the two floors where the telecommunications office was constructed were reinforced to withstand weights ranging from 730 to 1,460 kg/m2.

Refrigeration Plant

A refrigeration plant, regarded as the world’s largest at the time of construction, was erected on the roof, with three steam-powered units. The plant was installed on the top since the structure has no useable basement because it is all part of Grand Central Terminal. Large fan chambers were installed on the mechanical levels to distribute air to the other levels, and each story had two unique air supply systems. The ducts and pipes are required to service all of the floors, as well as an electrical and water pressurizer adequate for supporting all of the stories.

Lobby

A lobby spans the bottom two stories of the MetLife Building. A 23-meter pedestrian corridor at street level allows traffic to circulate between Grand Central Terminal and the Helmsley Building’s pedestrian arcades. Vanderbilt Avenue has a 31-meter-long entry arcade, with entrances positioned around 25 meters back from the pavement. The main office lobby of the building is located on the second story, at the level of the viaduct.

The lobby also has planters and a 12-meter enclosed patio, and there are 18 escalators in total. At the south end of the passage, four escalators connect to the Main Concourse, while 14 more connect from the corridor to the office lobby.

Interior Renovations

Warren Platner built 1,400 square meters of shop space in the foyer during a 1980s restoration. A staircase with alternating gray-granite and travertine risers was also placed in the middle of the lobby facing 45th Street. The staircase was 3 meters wide on the base floor, 6 meters wide at an intermediary landing where it was divided into two levels, and 9 meters wide at the mezzanine. At the bottom of the stairs, four triangular planters matched an orange carpet with floral themes on the mezzanine.

The foyer also featured strange semicircular discs hung from the ceiling or perched on poles. The lobby acquired black travertine and tile flooring during a Kohn Pedersen Fox makeover in the early 2000s, the stores were relocated to the sides, and the main staircase was eliminated. In the late 2010s, the stores were eliminated, and the lobby was re-covered in light-colored travertine. The rebuilt lobby has an oak-floored welcome room with a view of the entrance.

Artworks

The MetLife Building’s lobby was decorated with various works of art that made up the majority of the initial lobby ornamentation. Flight, a three-story wire artwork by Richard Lippold, is one such example. A sphere represents the Earth, a seven-pointed star represents the seven continents and oceans, and gold threads symbolize aircraft flight patterns.

A friend of Lippold’s, composer John Cage, had offered a musical program to accompany Flight (1962), consisting of 10 loudspeakers that would have played Muzak as visitors moved into or out of the lobby.

Lippold scrapped the plan, and the managers decided to play classical music instead. Manhattan (1963) by Josef Albers a mosaic mural of white, red, and black panels, topped the entry from the Main Concourse when it was opened.

Critical Reception

The octagonal shape of the MetLife Tower’s architecture was contentious when it was initially presented in 1959. In Progressive Architecture magazine, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy noted that the original tower designs “gave human scale and architectural identity”, which were “lost” in the redesign. Even the sketches for the structure were unsatisfactory to Walter McQuade. Internationally, Martin Pinchas, the Romanian architect, and Gillo Dorfles, the Italian critic, slammed Grand Central City. Given the site’s closeness to a large train terminal, architect Victor Gruen criticized the parking garage’s usefulness, while Thomas H. Creighton, the editor for Progressive Architecture, argued the area would be best left as an open courtyard.

The MetLife Building was intended to be a high-profile skyscraper just behind Grand Central Terminal that would alter Park Avenue’s design and the metropolis as a whole. Pietro Belluschi and Walter Gropius, two important leaders in contemporary architecture, would collaborate on the project. It was Emery Roth’s responsibility, though, to see that everything fell into place. Because of its location and design, the MetLife Building was one of the city’s most contentious structures at the time. Today, however, numerous preservationists are fighting to preserve and conserve the structure.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did the MetLife Tower Ever Have a Helipad?

The roof of the structure previously had a helicopter deck. Helicopter service commenced in December 1965, following a protracted permission procedure, and testing runs for the roof started with a Chinook helicopter. Architectural historian Reyner Banham stated in The Architects’ Journal in 1966 that there was really no better way to arrive into the island metropolis of Manhattan. For him, it would be a helicopter or nothing from that point forward.

What Is the MetLife Building’s Height?

The MetLife Building in New York has 59 stories and a height of 246 meters. It was advertised as the largest corporate office complex in terms of square footage when it first opened. As of November 2022, the MetLife Tower was still among the top 100 tallest buildings in the country.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “MetLife Building – The Controversial International Style Masterpiece.” Art in Context. January 2, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/metlife-building/

van Huyssteen, J. (2022, 2 January). MetLife Building – The Controversial International Style Masterpiece. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/metlife-building/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “MetLife Building – The Controversial International Style Masterpiece.” Art in Context, January 2, 2022. https://artincontext.org/metlife-building/.