Lighthouse of Alexandria – The Ancient Wonder of Alexandria

What happened to the Lighthouse of Alexandria, otherwise referred to as the Pharos of Alexandria? The Lighthouse of Alexandria was erected on the island of Pharos overlooking the city’s harbor between 300 and 280 BCE, under the reign of Ptolemy I. The Pharos of Alexandria, with a height of more than 100 meters, was so remarkable that it was included in the official list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. We will now delve deeper into the history and facts about the Lighthouse of Alexandria.

Shedding Light on the Lighthouse of Alexandria

| Architect | Sostratus of Cnidus (c. 3 BCE) |

| Date of Completion | c. 280 BCE |

| Function | Lighthouse |

| Location | Pharos, Alexandria, Egypt |

Although it is no longer standing, the structure’s lasting significance is that it gave the Greek term “Pharos” to the architectural style of any structure with a light used to direct seamen. The Pharos of Alexandria was, after the pyramids of Giza, the highest building in the world created by human hands, possibly influencing subsequent Arab minaret construction and certainly inspiring a series of imitation towers throughout Mediterranean harbors. Between 956 and 1323 CE, several earthquakes extensively wrecked the Lighthouse of Alexandria, which became a deserted structure.

The tower was the third-longest extant wonder, existing in part until 1480 when the remainder of its leftover stones were taken to construct the Citadel of Qaitbay on the site. In 1994, a group of archaeologists from France submerged themselves into the waters of Alexandria’s Eastern Harbor and discovered the ancient structure’s ruins on the ocean’s bottom. In 2016, the Ministry of State for Antiquities of Egypt revealed proposals to turn the Pharos of Alexandria and other underwater remains of ancient Alexandria into an underwater museum.

The Importance of the City of Alexandria

Alexandria is Egypt’s second-biggest city and the largest on the Mediterranean coast. Alexandria, founded about 331 BCE by Alexander the Great, expanded quickly and became a key center of Hellenic civilization, having replaced Memphis as Egypt’s capital. It was home to the Lighthouse of Alexandria as well as the renowned Library of Alexandria during the Hellenistic era. The library has been reborn as the ultramodern Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Its seaside Qaitbay Citadel, built in the 15th century, is now utilized as a museum.

It is a famous tourist destination as well as an important industrial center thanks to its natural oil and gas pipelines from Suez.

The city was built in the proximity of an Egyptian village known as Rhacotis. It held this position for about a millennium, from the time of Roman administration until the Muslim invasion of Egypt in 641 CE when a new headquarters was established at Fustat. For most of the Hellenistic and later antiquity, Alexandria was the cultural and intellectual center of the ancient Mediterranean. It was once the biggest metropolis in the ancient world until being surpassed by Rome. The city was a prominent early Christian center and the seat of the Patriarchate of Alexandria, which was among the most important Christian centers in the Eastern Roman Empire.

Both the Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria and the Coptic Orthodox Church claim this historic legacy in the modern world. The city had been extensively looted by 641 CE and had lost its status until re-emerging in the contemporary period. Alexandria became a significant international shipping center and one of the globe’s most important commerce centers beginning in the late 18th century, owing to the easy overland link between the Red Seas and the Mediterranean and the profitable trade in Egyptian cotton.

Origin

Pharos was a tiny island off the coast of the Nile Delta. Alexander the Great established Alexandria on a peninsula opposite Pharos in 332 BCE. The Heptastadion, a 1,200-meter-long tunnel that linked Alexandria and Pharos, was built later. The actual origin of the word “Pharos” is unknown. The Great Harbour, now an open bay, was formed on the tunnel’s eastern side; on the western side was Eunostos’ port, with its inner basin Kibotos extended to produce the contemporary harbor. Today’s city expansion is constructed on the silt that eventually enlarged and destroyed this tunnel between the current Grand Square and the contemporary Ras el-Tin district.

The island of Pharos, which formerly had the tower located at its most eastern point, has all but disappeared, leaving only the Ras el-Tin point, where the Ras el-Tin Palace was built in the 19th century.

Construction of the Pharos of Alexandria

The lighthouse was constructed in the third century BCE. Following the death of Alexander the Great, Ptolemy I Soter crowned himself emperor in 305 BCE and ordered the construction of the Great Pyramid. In total, the building took 12 years to complete and ended up costing 800 pieces of silver during the rule of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, his successor. The illumination was generated by furnaces at the pinnacle, and the structure was said to be built mostly of slabs of granite and limestone.

Strabo, who traveled to Alexandria in the late 1st century BCE, said in his encyclopedic text Geographica (1469) that Sostratus of Cnidus had a tribute to the “Saviour Gods” written in metal lettering on the Pharos of Alexandria. Pliny the Elder, speaking in the 1st century CE, asserted in his Natural History (77 CE) that Sostratus was the builder, albeit this conclusion is debatable. Lucian said in his 2nd century CE pedagogical book that Sostratus disguised his name behind plaster bearing Ptolemy’s name so that when the plaster ultimately came off, Sostratus’ name would be seen in the rock.

Description and Height

Regrettably, no one knows exactly what the tower looked like. Most ancient writers’ descriptions are vague, confused, and contradictory. Most accounts, however, agree that it had three stories and was white. Government offices and stables were said to be at the lowest part. The octagonal component was for visitors and provided a vista from the balcony, while the top half housed the light. Al-Balawi also characterized the tower as having a lengthy spiraling clockwise slope that was “big enough for two beasts of burden to traverse”.

Ibn Jubayr reported in 1183 that the Pharos of Alexandria “may be seen for more than 70 miles and is extremely old. It is most powerfully constructed in all dimensions and contends in height with the heavens. Because the view is so wide, explanation falls short, the eyes fail to fathom it, and words are insufficient”.

Despite repeated renovations following seismic damage, Arab accounts of the tower are constant. On a 30 by 30-meter square foundation, given heights change just 15% from 100 to 118 meters. According to Arab writers, the tower was built with big chunks of light-colored stone. The lighthouse was composed of three tapered tiers: a base square part with a core structure, a central octagonal component, and a circular component at the top. In the 10th century, Al-Masudi stated that the shoreline side had an engraving devoted to Zeus. Al-Idrisi, a geographer, examined the tower in 1154 and observed gaps in the walls all through the rectangular shaft, as well as lead used as a filler substance in between the block masonry at the bottom.

Existing Roman coins from the Alexandrian treasury depict a figure of Triton on each of the tower’s corners, with a figure of Zeus above. The lighthouse is described in detail by Arab explorer Abou Haggag Youssef el-Andaloussi, who explored Alexandria in 1166 CE. Balawi described and measured the inside of the rectangular shaft of the lighthouse. The inner ramp was reported as being roofed with brick at 189 cm, allowing two riders to pass at the same time. The ramp had four levels in clockwise rotation, with 18, 14, and 17 rooms on the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th floors, respectively. Balawi estimated the lighthouse’s base to be 30 meters long on every side, with a linking ramp 300 meters long and 10 meters wide.

The width of the octagonal part is 16 meters, while the diameter of the cylindrical component is 8.7 meters. The oratory’s apex was measured to be 4.3 meters in diameter. Ibn Battuta, a Moroccan scholar, and traveler who went through Alexandria in 1326 and 1349, wrote about the lighthouse after it was destroyed by the earthquake in Crete in 1303. Battuta observed that the destroyed state of the tower was only visible from the rectangular tower and entry ramp at the time. He reported that the tower was 30.8 meters on each side. Battuta outlined Sultan An-Nasir Muhammad’s proposal to erect a new lighthouse near the location of the destroyed one, but the Sultan’s death in 1341 prevented this from happening.

How the Lighthouse Worked

The structure may not have been a lighthouse at first. A light is not mentioned in some of the early tales of Pharos. And, despite accounts of the lighthouse’s interior, no texts mention the apparatus at the top that emitted light. It is thought that some sort of light was put at the top of the lighthouse at some stage and was most likely kept alight using oil rather than wood because at that time wood was scarce. However, Pliny the Elder describes the flame for the first time in the 1st century CE. In 944 CE, Al-Masudi mentioned a mirror at the peak of the tower, which is considered to have bounced the light across larger distances and perhaps to even reflect the sun.

Al-Gharnati also described a mirror, claiming that it “was relocated to mirror the sun setting and light ships ablaze while they were still at sea”. At the lighthouse’s top, there might have been a telescope. Ibn Khordadhbeh reported in the 9th century that there was a telescope in the tower that could reach as far as Constantinople.

However, the lighthouse performed more than one purpose. It is thought that Ptolemy I ordered the lighthouse to be constructed to inform everyone of his authority even after he died. And, given that, after the Giza pyramids, the Lighthouse of Alexandria was regarded to be the “tallest edifice in the world erected by human hands” at the time, the lighthouse most likely performed both functions.

Destruction of the Pharos of Alexandria

Earthquakes in 796 CE and 951 CE partly fractured and damaged the tower, accompanied by structural failure in the quake of 956 CE, and then another in 1303 and 1323. Earthquakes spread from two notorious tectonic borders, the Red Sea Rift and African-Arabian zones, which are 520 and 350 kilometers from the Lighthouse of Alexandria, respectively. Based on documents, the 956 CE earthquake was the first to trigger the structural failure of the upper 20 meters of the structure.

Renovations after the earthquake in 956 CE include the erection of an Islamic-style dome after the figure that had sat atop the monument was destroyed. The most severe quake in 1303 occurred on the island of Crete and was believed to have had a rating of VIII+. Finally, in 1480, the then-Sultan of Egypt, Qaitbay, used part of the fallen stone to build a medieval citadel on the bigger base of the lighthouse site. According to the 10th-century historian al-Mas’udi, during the reign of Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, the Byzantines dispatched an agent who converted to Islam, acquired the Caliph’s trust, and was granted permission to hunt for buried riches in the lighthouse’s base.

The story goes that the lighthouse was destroyed as a result of a plot by the opposing Emperor of Constantinople.

At that moment, the Caliph of Cairo, who at the time was in charge of Alexandria, issued an order for the lighthouse to be dismantled in order to retrieve the treasure after spreading rumors that a large fortune was buried beneath the lighthouse. He didn’t realize he had been duped until too much harm had been done, at which point he converted it into a mosque. Since travelers in 1115 CE claimed that the tower was still intact and functioning as a lighthouse, this tale appears improbable. The searches were conducted in a manner that compromised the Pharos of Alexandria’s foundations and it fell. The spy managed to board a vessel that was ready for him and sailed away.

Archeological Rediscovery and Research

Gaston Jondet published the first complete account of Alexandria’s underwater remains in 1916. That very year, he was succeeded by Raymond Weill, then in 1940 by Sir Leopold Halliday Savile. The lighthouse was discovered in 1968. UNESCO funded an excursion to send a group of marine archaeologists to the location, headed by Honor Frost. She verified the existence of remnants resembling a portion of the lighthouse. Exploration was halted because of a shortage of professional archaeologists and the region becoming a military zone.

In late 1994, a group of archaeologists from France, headed by Jean-Yves Empereur rediscovered the lighthouse’s physical ruins on the seabed of Alexandria’s Eastern Harbour. He collaborated with filmmaker Asma el-Bakri, who utilized a camera to record the very first underwater images of ruined columns and sculptures. The most important discoveries made by Empereur included slabs of granite weighing 50 to 60 tons and fragmented into many parts, five obelisks, 30 sphinxes, and columns with sculptures going back to Ramses II. Empereur and his crew used a blend of photography and GIS to classify over 3,300 artifacts by the end of 1995.

Around 36 pieces of Empereur’s granite blocks and other findings have been repaired and are now on exhibit at museums in Alexandria.

Satellite imagery has uncovered further remnants. Marine archaeologist Franck Goddio started exploring the other side of the port from where Empereur’s crew had operated in the early 1990s. Following satellite and sonar photography, further ruins of wharves, dwellings, and temples were discovered in the Mediterranean Sea as a consequence of tremors and other natural catastrophes. It is currently permitted to dive and see the remains. The UNESCO Secretariat is now collaborating with the Egyptian authorities on a project to add the Bay of Alexandria, along with the remnants of the Pharos of Alexandria, to the World Heritage List of submerged cultural monuments.

Reconstruction Proposals

Nearly 600 years after the Pharos of Alexandria was destroyed, proposals have been presented to rebuild the Seventh Wonder of the World. The concept was initially submitted to Governor Fouad Helmy in 1978 when diplomat Omar al-Hadidi recommended reconstructing the tower. By 1997, up to 32 businesses were bidding on the project of renovating the lighthouse, but some of their proposals appeared to thrust the tower too far into the contemporary world.

Some ideas called for a commercial mall inside the lighthouse, while another called for “lasers at the top instead of the conventional lantern”. As a result, Governor Mohamed Mahgoub canceled the project entirely. However, the proposal was revived in 2005 as “part of a set of initiatives toward a goal to improve the east harbor”. In 2015, plans were cleared to reconstruct the lighthouse just a few feet from where it had originally stood. As of 2022, though, it appears that the reproduction has yet to be built.

An underwater museum was planned in the late 1990s so that the public may see the sunken ruins of the lighthouse. Although the idea was put on hold during the Egyptian revolution in 2011, it was restarted in 2015. It is hoped that by establishing the location as a museum, and maybe a World Heritage site, the remnants of the Alexandria Lighthouse can be conserved and protected against pollutants and thieves. In an effort to deter archeological thieves, Egypt’s parliament adopted a measure in 2020 that would levy a $63,850 punishment on anybody who “obtains or distributes an antique or parts of it outside Egypt”.

There was also anticipation that the museum would help revitalize tourism in Alexandria, as well as provide opportunities for additional investigation on the archeological remnants of the lighthouse and other submerged ruins. Unfortunately, a lack of funding has delayed the establishment of the museum for many years. But Alexandra University planned a new project dubbed “Submerged” Heritage in 2021, with the goal of excavating underwater antiquities near Alexandria’s eastern harbor.

Legacy and Influence of the Lighthouse of Alexandria

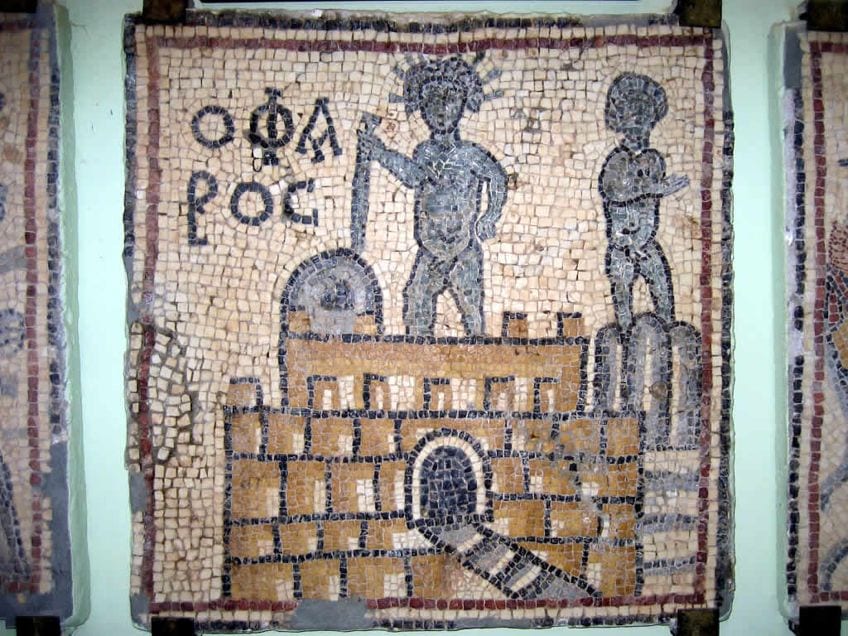

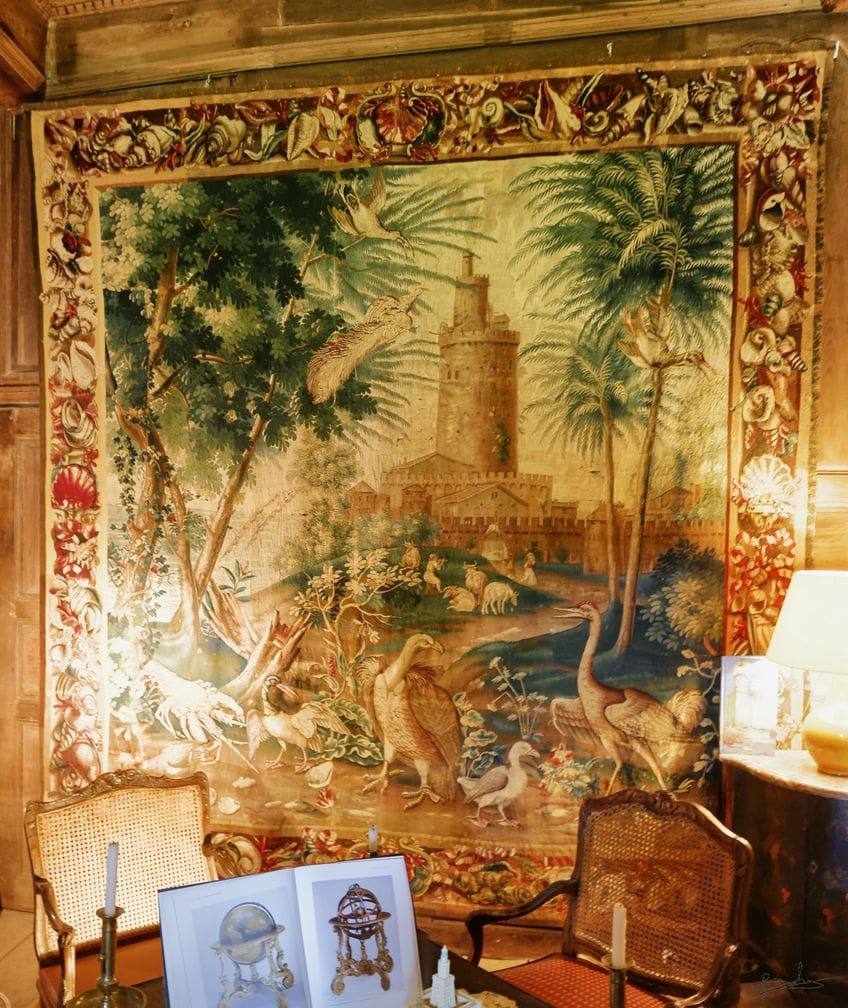

The Lighthouse of Alexandria has left an enduring architectural and cultural legacy. The architecture of the lighthouse was duplicated in various harbors across the ancient world, albeit none were as lofty as the Pharos of Alexandria. The lighthouse was also represented in countless mosaics, paintings, and coins. An ancient mausoleum at Abusir is also said to be a miniature replica of the famous tower.

Historians believe that the Pharos of Alexandria inspired the design of Arabic minarets.

However, the first minaret that resembled the architecture of the lighthouse was not built until 1304. The lighthouse would have been in a state of decay by then. As a result, it is thought that minaret architecture evolved from the Syrian church tower. Finally, the Lighthouse of Alexandria became so well-known that the term “pharos” came to denote any tall structure used to aid guild ships. In addition, the term for the lighthouse is formed from the Greek word pharos in various current languages, including the Romance languages.

The Pharos of Alexandria in Culture

The lighthouse is still a cultural emblem of the city of Alexandria. A stylized portrayal of the tower appears on the Governorate’s seal and flag, as well as on various city institutions, such as the seal of Alexandria University. Let’s take a look at how the Lighthouse of Alexandria has impacted architecture and literature.

Architecture

An ancient tomb near Abusir, 48 kilometers southwest of Alexandria, is claimed to be a scaled-down replica of the Pharos of Alexandria. It is known informally as the Abusir funeral monument and Burg al-Arab. It is a three-story, about 20-meter-high tower with a square foundation, an octagonal center, and a cylindrical top portion, similar to the structure on which it was supposedly built. It comes from Ptolemy II’s reign and was most likely erected around the same time as the Lighthouse of Alexandria.

Several early Egyptian Islamic mosques’ minarets followed a three-stage form comparable to the lighthouse, bearing witness to the tower’s greater architectural impact.

In Virginia, the George Washington Masonic National Memorial is modeled after the old tower. The “Pharos Lighthouse”, a fictitious rendition of the landmark, serves as the park emblem, centerpiece, and identity of the Islands of Adventure theme park at Universal Studios, which opened in 1999. The working lighthouse is located in the park’s Port of Entry section, evoking a literary, seashore explorers’ bazaar of real, ancient, and imagined world architectural features.

Literature

Julius Caesar mentions the lighthouse and its critical position in his Civil Wars (48 BCE). Gaining possession of the lighthouse aided him in subduing Ptolemy XIII’s armies: “Now, due to the narrow nature of the strait, no vessel may enter the port without the permission of those who occupy the Pharos of Alexandria. In light of this, I took the precaution of landing my forces while the enemy was engaged in combat, conquered the lighthouse, and established a garrison there.

As a consequence, safe access to his corn supply and reinforcements was ensured”. Josephus, the Romano-Jewish historian, also discusses it in his work The Jewish War (1880).

A customs inspector for Quanzhou, a southern port city, in the Song dynasty, Zhao Rugua, wrote about it in the Zhu fan zhi. Ibn Battuta toured the tower in 1326, finding “one of its sides in ruin”, but he was able to enter and record a spot for the lighthouse’s sentinel to sit, as well as several other rooms. When he revisited in 1349, he “found it in such a ruined state that it was not possible to access or climb up to the entryway”.

One of the Seven Wonders

Geographers and historians began creating lists of the world’s most stunning sites as late back as the 4th century BCE. Philo of Byzantium, Herodotus, and Callimachus of Cyrene all compiled lists of things to explore. However, because the Lighthouse of Alexandria and the Colossus of Rome were the final two “allowed into the canon”, it is thought that the list we now consider to be the “authentic” list of the Seven Wonders was produced some time in the 2nd century BCE.

The Colossus of Rhodes, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, the Temple of Artemis, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, and the Lighthouse of Alexandria are all on the list of the Seven Wonders. For roughly 50 years the Seven Wonders coexisted. The Colossus of Rhodes was knocked down by a quake in 226 BCE, and despite the Rhodians’ efforts to rebuild it, it ended up becoming a pile of shattered bronze, and the Seven Wonders never existed at the same time again. Only a small number of the original Seven Wonders remained by the time the list was “crystallized” during the Renaissance.

That concludes our look at the facts about the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Ptolemy I Soter commissioned the construction of a huge lighthouse in 300 BCE to direct ships into Alexandria and serve as a permanent symbol of his power and majesty. Ptolemy II, his son, and successor completed the building some 20 years later. The edifice simply contributed to the remarkable array of attractions in the ancient city, which already featured the Museum, Alexander’s tomb, the Serapeum temple, and the splendid library. The lighthouse was designed by Sostratus of Cnidus, the architect, according to various ancient sources, although he may also have been the project’s financial sponsor. The building was built on the point of the islet of Pharos, facing the Alexandria harbors. For that purpose, the lighthouse was devoted to two gods: Zeus Soter – whose devotional plaque on the lighthouse was created with half-meter-high lettering – and probably Proteus, the Greek sea deity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where in Alexandria Was the Lighthouse Originally Located?

On the island of Pharos, the tower was constructed close to Alexandria’s harbor in Egypt. The lighthouse was constructed because, according to the Greek historian Strabo, who toured Alexandria in the year 24 BCE, the shoreline there had rocks, shallow waters, and was low on both sides, making it difficult for ships coming in from the open sea to steer straight towards the harbor’s entrance. The lighthouse performed more than simply its basic job. It is thought that Ptolemy I ordered the lighthouse to serve as a constant reminder of his dominance, even after he had passed away.

What Happened to the Lighthouse of Alexandria?

Over 1,500 years ago, the Pharos of Alexandria withstood a powerful wave, and it still stands today. But the cracks that started to show up in the building towards the end of the 10th century were probably brought on by seismic shocks. This necessitated renovations that caused the structure to be lowered by around 70 feet. Pharos was rendered uninhabitable in 1303 CE by a powerful earthquake, making the lighthouse far less necessary. The lighthouse may have eventually fallen around 1375, according to records, but rubble remained there until 1480 when the stone was used to build a fortification atop Pharos that is still in existence today.

How Did UNESCO Help With the Pharos of Alexandria?

A grant from UNESCO was awarded to Abu El-Saadat in 1968 to outline the architectural remnants on the ocean floor, with a particular emphasis on what may possibly be a piece of the Pharos of Alexandria. According to Underwater Archaeology in Egypt, Vladimir Nesterov and Honor Frost were also summoned by the Egyptian authorities, and the three of them put together a list of 17 different lighthouse seafloor fragments. Frost pointed out that the figure would multiply one hundred times if they conducted a thorough investigation. The coastal region around Alexandria was declared a military zone as a result of the war being fought between Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and Palestine, according to UNESCO, forcing the suspension of archaeological studies. The study by Abu El-Saadat, Frost, and Nesterov still laid the framework for eventual excavations of the sites despite the delay.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Lighthouse of Alexandria – The Ancient Wonder of Alexandria.” Art in Context. January 11, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/lighthouse-of-alexandria/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 11 January). Lighthouse of Alexandria – The Ancient Wonder of Alexandria. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/lighthouse-of-alexandria/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Lighthouse of Alexandria – The Ancient Wonder of Alexandria.” Art in Context, January 11, 2023. https://artincontext.org/lighthouse-of-alexandria/.