Grant Wood Paintings – Looking at the Best Grant Wood Artworks

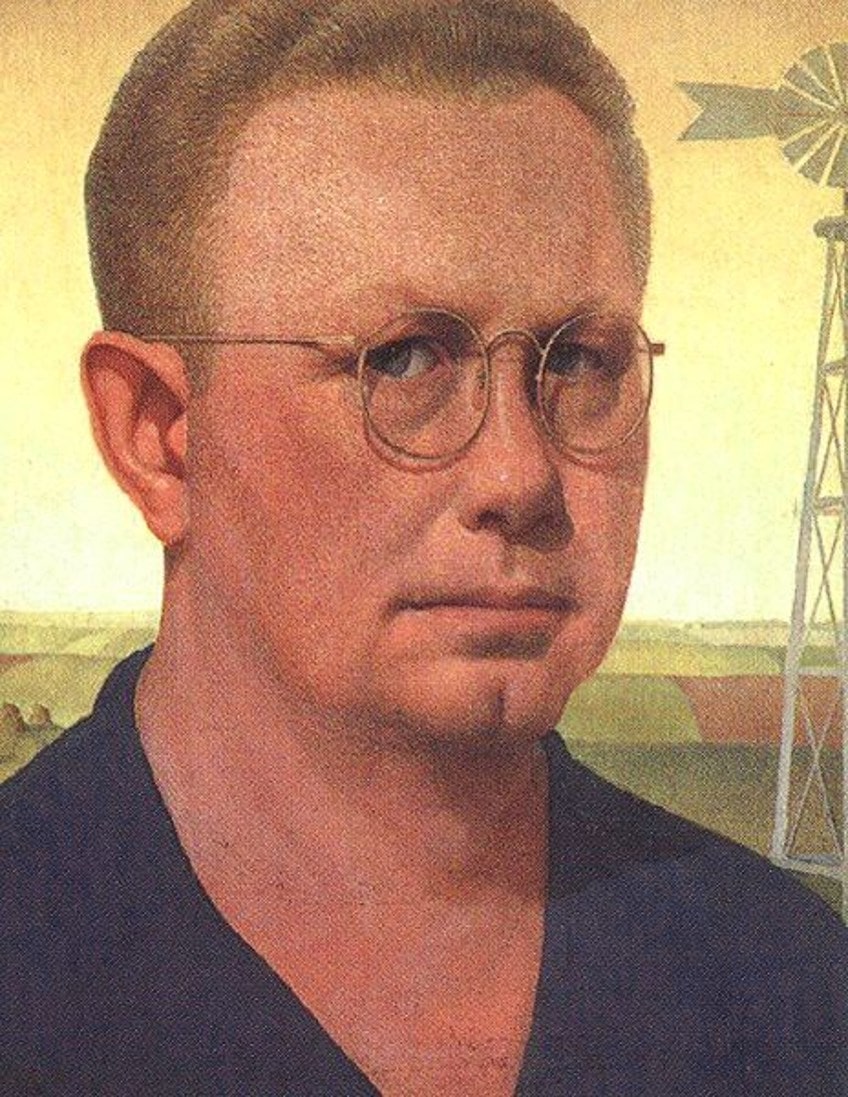

Grant Wood, most well known for his painting, American Gothic, was an American artist who helped establish the Regionalist movement. Grant Wood paintings are renowned for their portrayal of the American midwest. In this article, we will cover a brief introduction to Grant Wood’s biography and take a deep dive into the most important Grant Wood artworks.

A Brief Grant Wood Biography

Grant Wood was born on his family’s farm on the 13th of February, 1891. This picturesque environment would leave a life-long impression on the young boy and tremendously affect his subsequent reasoning and artwork, despite the fact that he would spend most of his time after the age of ten in the comparatively more urbanized area of Cedar Rapids, where his mom relocated Wood and his baby sister Nan after their dad passed.

Wood’s interest in drawing began when he was still in elementary school, and he already displayed great potential.

In high school, he honed his skills by designing scenery for performances and illustrating school magazines. He then attended the School of Design and Handicraft in Minneapolis after graduating in 1910. Wood’s artistic portfolio grew over the following few years as he learned to work with metals and jewelry, as well as create upholstery. He used these abilities to earn a living when he went to Chicago in 1913.

In the 1920s he traveled to Europe and displayed his artwork in Paris as well as visited museums in Italy and France, and studied at the Académie Julian. He emerged from these excursions deeply influenced by the Impressionists, whose pastoral compositions appealed to his own tastes. Upon seeing the artworks of the 16th-century Flemish and German masters, who displayed great attention to small details and realism, he decided to start integrating their style into this artwork.

His unique style and subject matter make Grant Wood’s artworks an important addition to the American art movement.

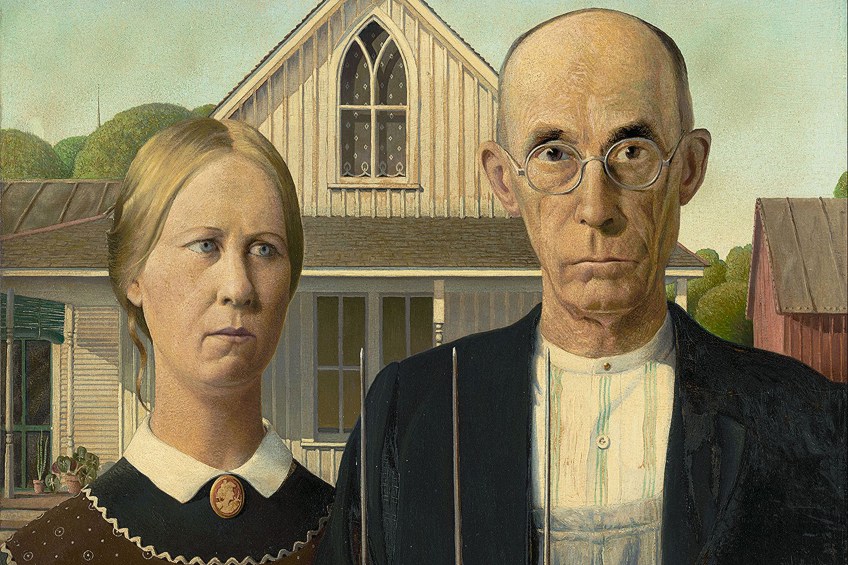

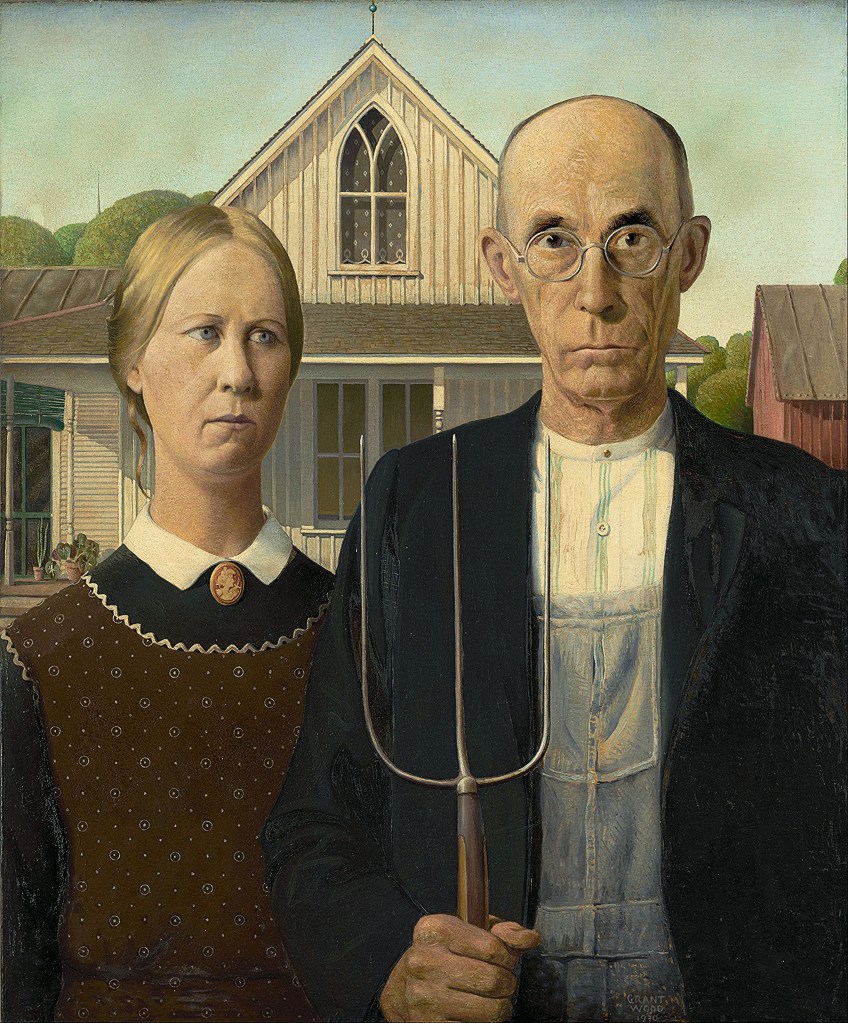

American Gothic (1930)

| Date Created | 1930 |

| Medium | Oil on Beaverboard |

| Dimensions | 78 cm x 65 cm |

| Currently Housed | Art Institute of Chicago |

American Gothic by Grant Wood is undoubtedly among the most well-known 20th century American artworks. A young-looking girl dressed conservatively poses beside an elderly gentleman dressed in a black blazer over dungarees and a collarless top, her eyes diverted. The old farmer holds a pitchfork – an outmoded implement at the time – and stares at the spectator.

In the background is a simple white house with a beautiful gothic window – a popular element of the period’s “Carpenter Gothic” architecture – situated between their heads. The design of the woman’s clothing is echoed in the window curtains. Just above the female’s shoulders, a few planted shrubs can be seen on the veranda. The backdrop is made up of neat lush greenery with a glimpse of a church tower and a red farmhouse.

The Chicago Evening Post released a picture two days before the beginning of the show at the Art Institute of Chicago when the artwork had its premiere.

The stone-faced figures, whom many mistook as a married couple, sparked a flurry of attention, and Wood became well-known across the country almost immediately. Wood stated of the painting, which he claimed depicted a girl and her dad rather than a married pair as several had thought, that he just fabricated some “American Gothic” people to pose in front of a home of this style. His dentist and his younger sister Nan served as references for the pair.

It demonstrates Grant Wood’s artwork’s extraordinary, intrinsic volatility; views of his portrayals of Midwestern characters, American tradition, and farming practices elicited conflicting emotions in 1931 just as much as they do now.

The artwork’s reaction and subsequent existence illustrate the odd ambivalence of this supposedly plain picture. It creates as many concerns as it resolves. Its title says that it is American, but what precisely is it that is emphatically American about it? If this is a tribute to the plain inhabitants of the Midwest, why has the painter shown the pair as unhappy? Is it intended to express incongruity? Is it a satire of Identities? Is the term just a description of the building’s stylistic details?

The issues of national identification that occupied Wood’s adult life play an essential part in interpreting his works.

The 1930s witnessed a retreat from rising internationalism into a significant trend in pop culture with a clear veneration for the virtues of cooperation and hard labor that were viewed as vital to the national psyche and most completely expressed in America’s small farms and towns. Wood’s mysterious pair became legendary, maybe because of, rather than despite, the artwork’s vagueness.

Midnight Ride of Paul Revere (1931)

| Date Created | 1931 |

| Medium | Oil on Board |

| Dimensions | 76 cm x 102 cm |

| Currently Housed | Metro Museum of Art, New York |

Edward Wood’s 1931 rendition of Paul Revere’s famed journey across Massachusetts communities alerting of the coming of English forces was prompted by the famous poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Dramatic lighting illuminates the artwork’s middle, which depicts the village from an overhead viewpoint, with the tips of chimneys in the front.

Revere is portrayed on horseback as he rushes by a bleached chapel on the side. In his path, a few residents emerge from their dwellings. A black road runs across the backdrop on each side of the brightly illuminated village, passing over undulating hills with beautifully round trees.

Wood stated that as a youngster, he envisioned alerting people of a dreadful hurricane in a similar manner, which may have influenced the lighthearted manner in which he presented the narrative. . The environment is constructed around wildly exaggerated ornamental geometry, with every item reduced to beautifully rounded or rigidly linear forms. The precision of the painting technique was a later development, but the imposition of modern style on the countryside reveals his professional origins.

Although he had no desire to create in a Cubist or completely abstract manner, he desired for his artwork to have a contemporary appearance.

His answer was to apply current design ideas to his settings – his plants and slopes have the unrelenting repeating regularity of an Art Deco building. The overhead view is reminiscent of a typical technique in Currier and Ives’ pictures, which were experiencing a revival in interest in the 1930s. The topic matter and ornamental approach have been viewed in conflicting ways.

Owing to the humorous approach to the topic and the sardonic spectacle of the environment, one interpretation sees this work as offbeat and reflective of the counter-cultural debunking psyche of the 1920s, reconciling Wood with H.L Mencken, recognized for his derision of widespread American tastes. Yet others have associated Wood’s portrayal with a larger colonial-era traditionalist movement in America, most notably John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s reconstruction of Williamsburg, Virginia.

Though Wood gave the topic a particular narrative approach, with the overhead and pictorial surroundings, the artist’s intention is a reworking of national mythology, based on the artist’s opinion that America had a great culture deserving of conservation and admiration.

Victorian Survival (1931)

| Date Created | 1931 |

| Medium | Oil on Board |

| Dimensions | 81 cm x 66 cm |

| Currently Housed | Carnegie-Stout Public Library, Dubuque, Iowa |

A conservative, terse lady in muted colors directs her attention towards the spectator. She has a ribbon choker wrapped around her extremely long neck. In the manner of the mid-nineteenth century, her hairstyle is separated down the center and pushed back. The only thing in the backdrop is a desk with a rotary phone, which mirrors the model’s long neck.

The picture was inspired by a photograph of the artist’s great aunt, and its arching top and rich tonal colors are reminiscent of a 19th-century darkroom technique’s color palette and form. In his incomplete memoir, Wood reflected on his Aunt Matilda, wondering “how she could close her eyes each evening” with her hair pushed back so firmly.

She was more intelligent and aspired to literature than some other relatives, but she was also quite strict, which he considered both thrilling and onerous.

The appearance of the phone, which stands in the location in which a bible or a bouquet of flowers would normally provide scene decoration for portraiture, disturbs the impression of a 19th-century snapshot. A rotary telephone was the most advanced model of communication at the time. Its earphone arrogantly points up at the person, and one would think that her strained look is due to it ringing loudly at her side.

This artwork, like many of Grant Wood’s paintings, is about cultural difference, about the insurmountable chasm between the rustic, Victorian environment in which he was reared and the contemporary, metropolitan world in which he dwelt as a grownup.

The lady and the telephone are diametrically opposed: she is closed to strangers and emotional expression, while the phone represents a twanging, invasive world to which she can never adapt. Wood’s era of painters responded to the world’s breathtaking rate of growth in a variety of ways. Although Precisionists praised innovation, many lamented the loss of traditional ways of living.

Wood addressed the topic with a sense of humor, but like Edward Hopper and Walker Evans, he is sensitive to “the durability, grace, and individuality of late-nineteenth-century America being supplanted by the contemporary world.”

In Wood’s depiction, the misplaced past is both a source of amusement and a source of compassion and empathy.

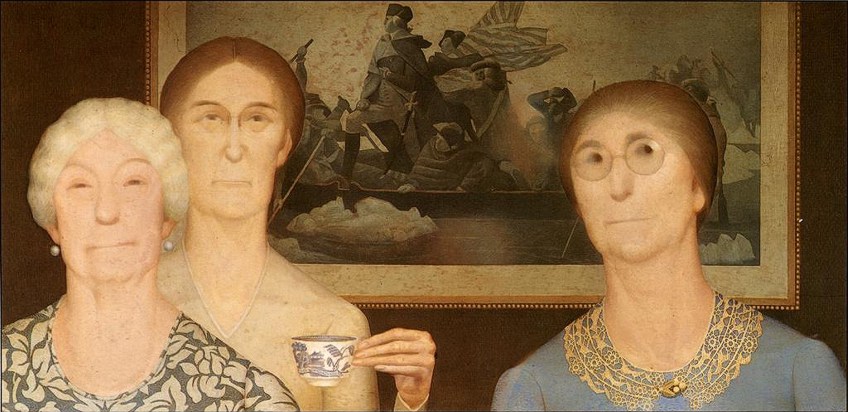

Daughters of Revolution (1932)

| Date Created | 1932 |

| Medium | Oil on Masonite |

| Dimensions | 50 cm x 101 cm |

| Currently Housed | Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati |

Wood was tasked with designing a stained glass at the Veterans Memorial Coliseum in 1927. He chose glass manufactured in Germany because he was dissatisfied with the quality of local glass suppliers. The local branch of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) objected to the use of a Nazi resource for a World Conflict I monument since Germany was an adversary of the United States throughout the war. They voiced a residual anti-German feeling in America, and other Cedar Rapids residents objected to the Foreign origin as well. As a consequence, the window wasn’t officially devoted until 1955.

The DAR was characterized by Wood as “those Tory girls” and “people seeking to establish up a nobility of inheritance in a democracy.”

Wood painted Daughters of Revolution five years later, which he considered as his lone parody. He highlighted the juxtaposition of three elderly women in fading clothes against the epic picture of Washington Bridging the River, which was produced in Germany by Emanuel Leutze. Wood dressed the women in his mom’s clothes, along with a lace collar and a brooch he acquired for her while in Germany.

The contrast of these ladies with the legendary portrait of George Washington depicting one of his combat achievements has piqued the interest of critics.

The founders are shown as cross-dressing characters in this artwork. In his book, Evans examines Wood’s suspected homosexuality, as well as his preoccupation with what Adams refers to as “sexual alterations.” Reviewer Deborah Solomon believes that Evans overestimates the evidence for Wood as a gay and takes this viewpoint too far in understanding his artworks in her assessment of Evans’ book.

She contends that Wood is more accurately defined as asexual.

“He yearned for the companionship of the deceased and plugged back through time in his beautiful and melancholy works,” Solomon says of Wood, who is tormented by the past. He deserves to be recognized as one of America’s most important eccentrics.” “It’s really terrible artwork,” Wood said. It is carried by its topic.

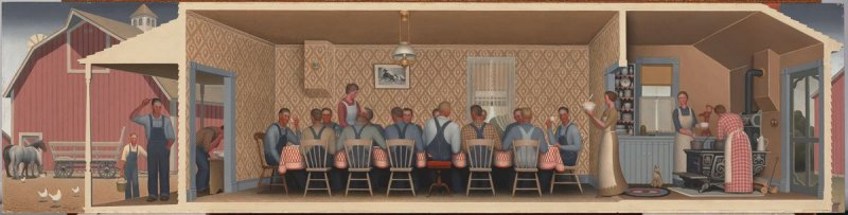

Dinner for Threshers (1934)

| Date Created | 1934 |

| Medium | Oil on Hardboard |

| Dimensions | 45 cm x 182 cm |

| Currently Housed | Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco |

This triptych-style artwork was a prototype for a fresco project. The contract never came to fruition, although the picture was extensively shown. The triptych structure, as well as Wood’s precise, matured technique, were influenced by altarpieces by North Renaissance artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Hans Memling. Wood’s boyhood experience of harvesting season is depicted in Dinner for Threshers.

The left part depicts agricultural workers getting ready to join the company inside for a midday lunch. “1892” is engraved at the pinnacle of the barn’s roof, placing the picture in the first year of Wood’s existence.

A throng of laborers gathers around a desk sitting on uneven seats in the center area. As they had all respectfully removed their hats inside, their pale brows contrast with their burnt features. A female enters the room from the pantry, carrying a full dish. The third portion depicts two ladies in the kitchenette, working at the wood-burning oven, as a cat looks on.

According to Grant Wood’s biography, this yearly gathering is a fun day for the farming community.

The shredding equipment usually appears like an enormous dragon one day in early August, after the wheat had been chopped and shocked – piled erect for curing. All of the surrounding producers would arrive with hayracks to grab the wheat shocks and transport them to be separated. This cooperative setup lasted many weeks, with everyone going from field to field until all of the wheat was harvested. Every harvest day, at noon, the employees went to the farm for a meal.

The piece shows Wood’s appreciation of community labor and Midwest agricultural life’s social customs.

Wood’s careful approach drew a lot of attention. Viewers mailed him notes in which they questioned its veracity. The painter justified the arrangement as being from his recollection – even right down to the design of the crockery on the pantry shelf – and questioned why audiences would permit him to divide a home yet quarrel over “the location of shadowing under poultry” and other minutiae. This answer harkens back to his early days as a middle school teacher when he would focus on the fundamentals of looking at current art.

The Perfectionist (1937)

| Date Created | 1937 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 40 cm x 30 cm |

| Currently Housed | Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco |

Illustrations, designing, and commercial artwork were important aspects of Wood’s creative process during his lifetime, but they became much more important to him in the mid-1930s for financial reasons. He received an invitation to design a limited version of Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street in 1936, causing the St. Louis Dispatch to write that the writer and artist have become so well-known for their portrayals of rural regions in America that such a partnership seems more than merely suitable.”

The assignment contained nine drawings, most of which depicted the residents of Gopher Prairie, Minnesota, the imaginary town in which the story takes place. The novel was printed in a limited edition of 1500 copies, each autographed by the artist.

These preliminary sketches on beige packing materials mirror the publication’s eventual color theme and fabrics, which Wood assisted in selecting – tan rag material with a yellow and blue linen covering.

Wood constructed broad identities for specific characters, identifying the small-town kinds through clothing, mannerisms, and characteristics. Looking up from below, the drawings exaggerate the eyes and hands to show the characteristics of the individuals. Carol Kennicott, the person on which this painting is based, is one of the more fortunate individuals and a campaigner and champion of arts and the aesthetic, gazing quizzically out of an organza window at the little village that would never compare favorably to her ideals.

Despite the fact that this distressed woman is a likable person in the novel, Wood makes fun of her by inserting a small fault – a button that is becoming unfastened.

In other related works, such as The Booster, a fellow of the village’s economic society, is depicted as having just arrived in the village to dabble in property as a big, uncouth, funny man with slitted eyes and dazzling clothing. While Lewis and Wood were both identified with rural America, Wanda Corn notes that they “earned their names depicting quite distinct sectors of regional America.”

Wood’s characters were farmers and traditional kinds, but Lewis’ figures were more contemporary, but also more smug, puritanical, and narrow-minded. Lewis belonged to “an age that rebelled against the community, whereas Wood belonged to one that had reverted to it.” This contrast in perspective may be observed, for instance, in Wood’s gently sarcastic portrayal of The Perfectionist – a lady who strives for sophistication and elegance and perceives her tiny town as lacking in these areas.

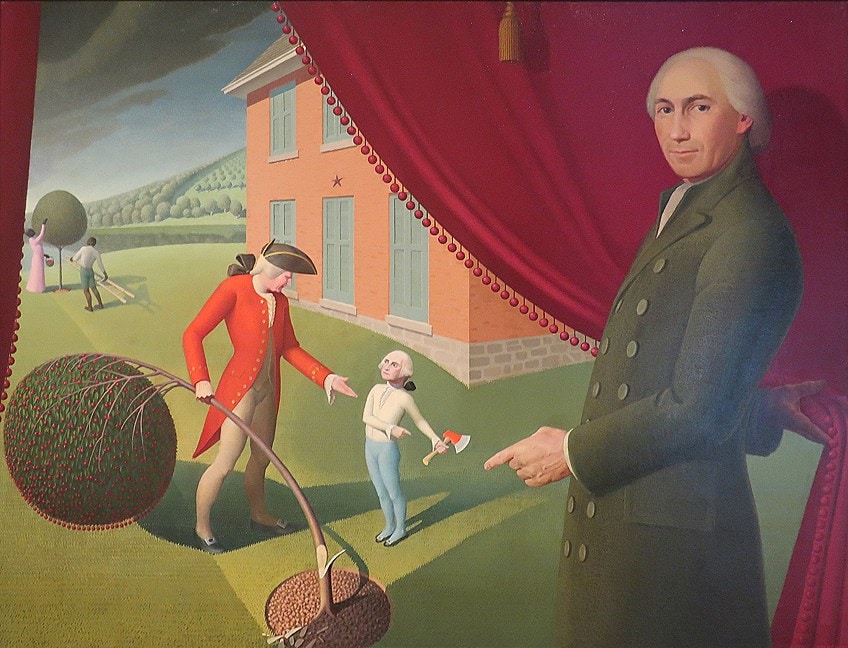

Parson Weem’s Fable (1939)

| Date Created | 1939 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 127 cm x 97 cm |

| Currently Housed | Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth |

Wood’s late piece is an offbeat portrayal of Parson Weems’ renowned story about George Washington’s integrity. Weems appears in the front, holding back a tasseled drape. Behind the drape, a scenario from his fable about youthful George Washington admitting to chopping down a cherry tree plays out. The young kid Washington points towards the hatchet in his hands, admitting to the damage of the precisely round-topped shrub that his austere dad clutches whilst disciplining him for his rash conduct. A neat brick home extends straight into the horizon, where two employees care for an equally symmetrical tree, and slopes clad in neat vegetation roll out into the horizon.

He claimed that he intended for this effort to help revive interest in the cherry tree and other pieces of American tradition that are just too valuable to lose.

The background of Europe’s developing totalitarianism forced Wood to boost nationalism via respect for Washington’s integrity and the example of parenthood that Weems wanted the story to represent. The painter was also reacting to an essay by novelist Howard Mumford Jones, who urged authors and painters to establish a new form of patriotism that was free of bigotry, economic selfishness, or ethnic snobbery – in order to restore the value of tales, mythologies, and historical accounts.

On this subject, he stated, “The most efficient way to achieve this is to take these historical narratives for what they are – myth, and present them in such a way that reasonable, intellectual people of our time can embrace them.”

To that purpose, he incorporates the underlying deception into the portrayal of this piece; Weems’ tale was a made-up narrative inside a tale.

Wood portrays the author physically removing the curtain off his work. Weems is also an altered personality, a fellow legend maker who, like Wood, aimed to enhance the national imagination with vivid stories of America’s history. Several layers are also visible. The most startling aspect, a six-year-old child with classic headgear, adds a sense of dramatic silliness while also signaling that this isn’t a true account about a real child, but an “origins legend” of a Father of the nation.

The environment and composition are ordered, beautiful geometry served as an odd contrast to the old-man/boy protagonist’s ludicrous look.

Spring in Town (1941)

| Date Created | 1941 |

| Medium | Oil on Wood |

| Dimensions | 66 cm x 63 cm |

| Currently Housed | Swope Art Museum, Terre Haute, Indiana |

A youthful man without a shirt prepares the veggie garden for springtime sowing in a tiny village with numerous buildings nearby. A lady spreads blankets to air on a line, as little toddler tugs on the limbs of a blooming tree. A guy trims his yard, a man mounts a ladder to his rooftop, a pair beats a carpet, and a youngster pulls a cart along the pavement in the distance. Wood paints a vivid picture with clean, precise lines, giving the observer a view from just above the action.

From this angle, we get a full picture of work and life in a small town, as well as its smallest details. The artist said of this artwork as well as another created as its accompanying piece, “In creating these works of art, I had in thought something which I hope to express to a reasonably large audience in America – the image of a region affluent in the art forms of tranquility, a cozy, endearing country, vastly deserving of any selflessness required to its survival.”

Whereas Wood’s motivations are clear in this and many other paintings, there is yet another tier of meaning just beneath the surface.

With the young man in the foreground, there is an undeniably homoerotic undertone in this work. His muscular shoulders and back are immediately visible, accentuated by a tan, and his work overalls tightly cover his backside, which left very little to the imagination as he can be seen bending over to work with his shovel in the garden. Rumors of the artist’s sexual preferences began to spread near the end of his lifetime.

Due to homosexuality being a crime in that era, he preferred to keep his preferences to himself, and yet his artworks are both the portrayal of the beauties of small Midwestern American towns as well as the revelation of his inner fantasies.

Wood relied on his own childhood recollections of rural life but mixed them with parts of his current life, such as individuals he knew, houses he observed in the area, and his sentiments towards friends and family. Another of Grant Wood’s artworks Saturday Night Bath was rejected by the US Post Office in 1939 on the basis that it was sexual.

Wood may argue naively that he was showing two naked men soaking after a long day working among the crops, but the homoeroticism is apparent. Richard Meyer, an art historian, cautions against identifying Wood as a gay painter, but he does not dispute his homosexual aesthetics, which appears to sexualize not just manual work but also the environment itself, confounding Wood’s image as a defender of traditional ideals.

And with that, we have come to the end of our list of important Grant Wood paintings. Grant Wood’s artworks have earned their place in art history for their unique depictions of rural American life. From his early success with American Gothic to his later works, his art is remembered for his sometimes humorous portrayals of uniquely American characters and places.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which Is the Most Famous of All Grant Wood’s Paintings?

Grant Wood liked to portray characters of rural American life. His famous painting American Gothic was his most famous artwork. It features a man and woman in front of a farmhouse with a Gothic architectural element, hence the name.

Was Grant Wood Gay?

Despite living in an era where homosexuality was a crime, it is believed that he was gay. He did, however, marry a woman by the name of Sara Maxon in 1935, but they divorced four years later. It is said that his sexual preferences can be observed in his paintings.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Grant Wood Paintings – Looking at the Best Grant Wood Artworks.” Art in Context. October 7, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/grant-wood-paintings/

Meyer, I. (2021, 7 October). Grant Wood Paintings – Looking at the Best Grant Wood Artworks. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/grant-wood-paintings/

Meyer, Isabella. “Grant Wood Paintings – Looking at the Best Grant Wood Artworks.” Art in Context, October 7, 2021. https://artincontext.org/grant-wood-paintings/.