Giorgio Morandi – The Life and Art of Italian Painter Giorgio Morandi

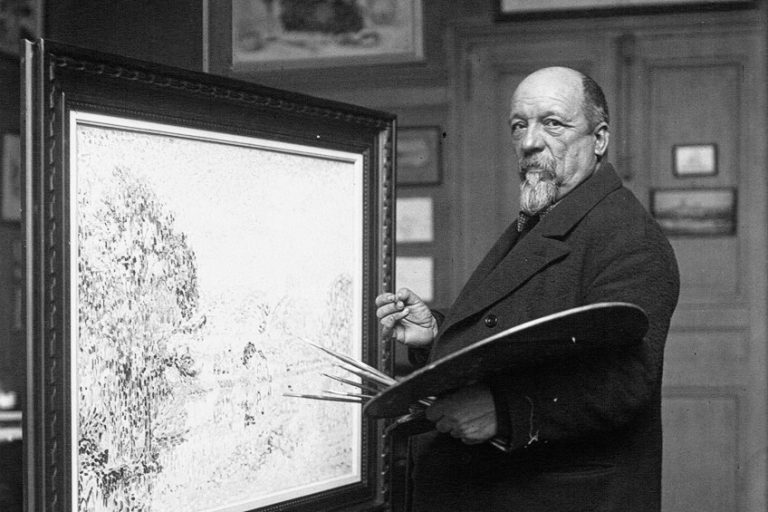

Giorgio Morandi labored in a modest room in the center of Italy, quite a distance from the artistic epicenter of his day, to tackle the issues related to art, the various questions surrounding the contemporary arts, striving for the pattern and order that underscores the art of depiction itself. With a restricted range of ordinary items and recognizable landscapes portrayed in muted tones and gentle light, Giorgio Morandi’s paintings combined the long tradition of Italian art with 20th-century modernity. With painstakingly regulated tonal relationships and a sense of real space and light, his still-life paintings continued a tradition of pictorial art while inventing a minimalist look that proved relevant in the face of abstraction.

Giorgio Morandi Biography

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | 20 July 1890 |

| Date of Death | 18 June 1964 |

| Place of Birth | Bologna, Italy |

Giorgio Morandi’s paintings were based on simple and universal designs, but his painstaking paint technique and attentiveness to a specific Italian illumination suggested an autobiographical element. Regardless of the fact that he portrayed everyday items, critics noted how his depictions of these objects conveyed a sense of Morandi’s personality, monastic habits, and Italian surroundings.

His cohesive body of work would be important for its meticulous examination of commonplace parts of daily life, suffusing them with profound meaning by stressing their artistic beauty and simplicity.

Childhood and Education

Giorgio Morandi was the eldest of five children born into a middle-class family in Bologna, Italy. Morandi’s early love of art disturbed his father, who wanted his son to accompany him in his export business; Morandi attempted unsuccessfully in 1906.

After this, he enrolled in the Bologna Academy of Fine Arts in 1907.

His choice to pursue painting as a career is influenced by his father’s inability, his mother’s trust in her son’s ability to achieve his objectives, and his father’s reluctance to change his concentration on art regardless of his father’s best efforts.

Early Training

Morandi continued his study with the support of his mother when his father passed away suddenly in 1908, forcing him to fend for his mother and younger sisters. During this time, he was introduced to Cubism and Futurism, which impacted his early work. “Only an appreciation of the most significant triumphs in painting over the years could help me establish my path,” Morandi said in his 1928 autobiography.”

He qualified in 1913, but continued his study by traveling around Italy, notably to the Venice Biennale. These excursions would eventually prove significant, as Morandi seldom traveled overseas after the 1920s, and much of his future exposure to painters came from art publications.

He was particularly interested in the work of Impressionists like Claude Monet, as well as subsequent greats such as Georges Seurat and Paul Cézanne. He also traveled within Italy, particularly to see galleries and exhibitions, and was far more well-traveled than some historical sources portray him to be.

Morandi’s initial career was cut short by his enlistment in the Italian army during the years of World War I.

Mature Period

Morandi previously worked in the Metaphysical School manner starting in 1916 and engaged in group exhibits centered on this movement. It has been said that this period gave him the courage to explore further because it was the first time his art was noticed on a world scale. Despite his close contacts with notable painters of the school, such as Giorgio de Chirico, he later contested the influence of this approach on his following work, declaring that he never represented whatever could not be observed with his own eyes.

Even if history is difficult to track here, as it is in most of Morandi’s life, art historians see “pittura metafisica”, or metaphysical painting, as a watershed moment in his evolution.

Early encounters with modern ideas, such as Carlo Carra’s 1910 statement, “artistic conception requires a diligent, meticulous, vigilant strength of character and necessitates a continuous work not to lose the manifestations, and are little else more than lightning bolts of everyday things that when they highlight generate the necessities that are so valuable to us modern artists.”

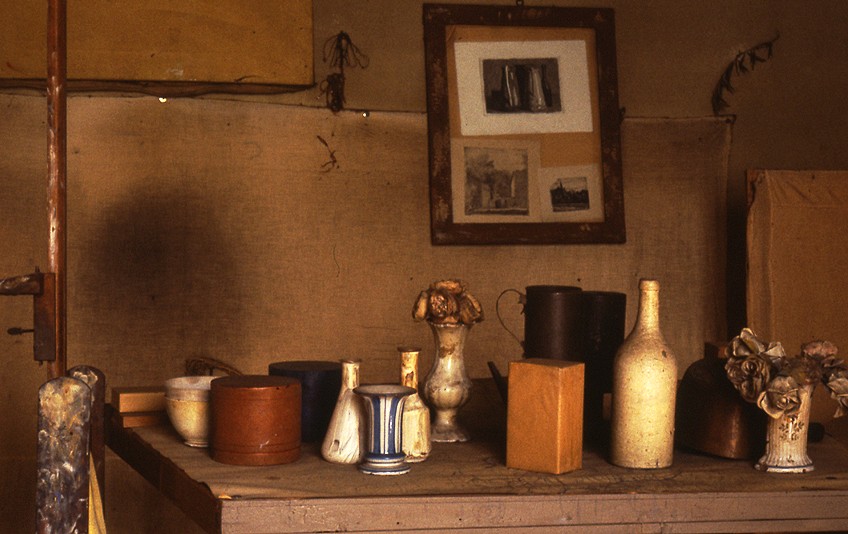

This theme appears to resound strongly throughout Morandi’s creative journey. Morandi quickly acquired the modernist approach for which he is best recognized, with simple, softly stunning still lifes of everyday objects like cans and bottles, as well as landscapes depicting his environment. He created a serial technique in his still life paintings, depicting groupings of objects with only minor modifications in spacing or placing. While the bulk of these works were paintings, Morandi often employed etchings to depict them in the limited black and white palette.

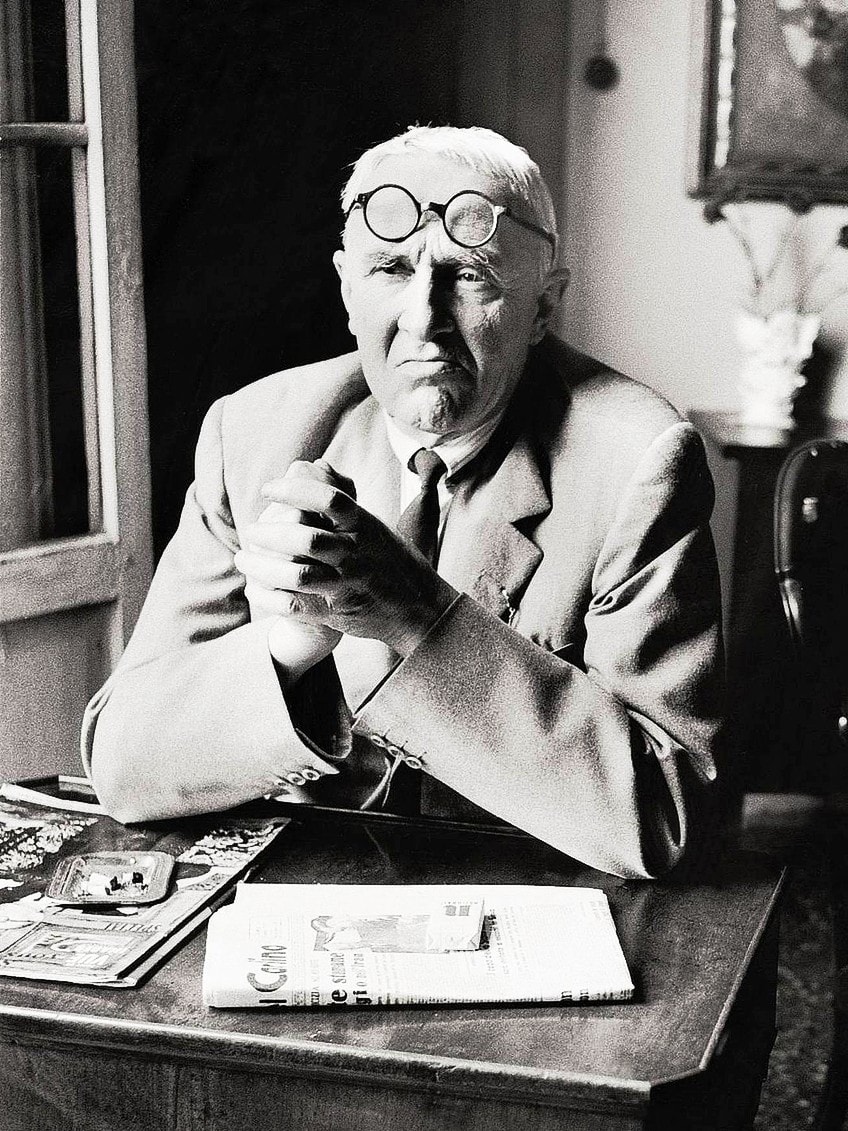

For many years, Morandi maintained a peaceful daily routine. His workshop, a small room in a flat he shared with his mother and sisters, was where he did most of his work.

Despite its diminutive size, the room was well-lit and provided a panorama of the rural countryside from his windows, one of two views he depicted on a regular basis. The second location was influenced by views from Grizzana, a mountain community where Morandi spent many months with his family and eventually established a vacation house as well as studio space.

The dust that gathered on the various bottles and items Morandi utilized in his still lifes adds to his monastic existence. After seeing the artist’s workshop, historian John Rewald stated, “No skylight, no enormous vistas; an average room of a middle-class flat illuminated by two ordinary windows.” But the remainder was exceptional: boxes, bottles, vases, and all types of vessels in all kinds of forms, scattered over the floor, shelves, and table. The sides of the bookshelves or desks, as well as the surface tops of boxes, jars, or similar containers, were coated in a thick layer of dust.

Giorgio de Chirico stated in 1922 that Morandi was attempting to rediscover and invent everything on his own. This might be the essential insight to comprehending Morandi’s tenacious pursuit that would consume the rest of his life.

He valued the practice of study and practical preparation and chastised contemporaries who dismissed these customs; when he viewed the creations of the Abstract Expressionists much later in life, he said that Jackson Pollock “simply jumps in before he learns how to swim.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQx8US4jUPk

Despite his poor and solitary existence, Morandi swiftly established himself as a significant and important modern artist. His command of a formal language of color, light, and arrangement began to garner notice, blazing in the face of current painting in the manner of Surrealism or abstraction. Morandi was named “one of the greatest painters living” by Roberto Longhi in 1934. Morandi was regarded locally largely as an unobtrusive professor of etching, not as the master to be remembered in the manner of Carracci and other Bolognese legends.

Teaching art was an essential aspect of Morandi’s life, mirroring his artistic dedication to the method and structural experimentation.

He taught drawing in local primary schools for years before entering the Bologna Academy of Fine Arts, as Head of Etchings in 1930. He would stay at the Academy for years, even as he rose to worldwide prominence, preferring the quiet and security of a regular post distant from Europe’s major cultural hubs.

Late Period

Many world events passed, but Morandi steadfastly maintained to focus on largely still life, working with a narrow variety of comparable compositions over the decades to refine his technique and form. Morandi may have fallen in love with the basic things he acquired at thrift stores, staring at and analyzing their forms day and night – such emotion may help explain his great attachment to his chosen topics.

His rare landscapes reflected the world’s growing modernity; the wires and antennae that were now seen from his workshop window started appearing in his 1950s paintings, although abstractly.

Morandi was an instructor of etching at the Academy for 26 years, retiring only in 1956 to pursue painting full-time as a well-known painter, becoming financially secure from the sales of his work (previously, he and his family had financial difficulties, and he clashed with his dealers over sales and adequate representation.)

Even in his later years, Giorgio Morandi preferred to focus on his art rather than on exhibits and international acclaim. He reportedly turned down an exhibition offer because the organizers were overly insistent: “They truly try to deprive me of that tiny degree of quiet that is vital for my work.”

Giorgio Morandi’s Paintings

Morandi, who was focused on his own pictorial investigations at a period when the avant-garde was concerned with abstract painting, looked unimpressed by theoretical art trends. Nonetheless, his concerns were comparable to those of his contemporaries, as he regarded color, lines, lighting, space, and brushwork as issues to be addressed via rigorous study and precise modifications.

Morandi continued the history of Italian painting into the twentieth century with his attention to technique and careful accuracy, but he gave it fresh significance with his simple aesthetic and non-narrative emphasis.

With their minimalist palettes, precise lines, and exact brush strokes, Morandi’s still lifes are undeniably modern, and his concern for skill and the physicality of the painted surface tied subsequent artists to the epic legacy of the still life and landscapes forms.

Natura Morta (Still Life) (1914)

| Date Completed | 1914 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 25 cm x 48 cm |

| Current Location | Collection of Augusto and Francesca Giovanardi |

It is one of Giorgio Morandi’s first paintings and depicts a wooden table with a variety of monochrome common things. Notwithstanding the image’s abstractness, the viewer may distinguish an erect book with its binds facing away, which is put in front of a transparent bottle, a pitcher, and a jug.

An abstracted picture of a room appears in the area behind the table, indicating a wall, windows, and another table. Despite the fact that the objects are completely lifeless, they are created in a way that conveys fragility and motion, with a diagonal thrust forcing them towards the viewer.

Morandi experimented with developing genres in his early years; this painting exhibits elements from both Cubism and Futurism. Morandi’s still life is reminiscent of Futurism, with each object depicted to simulate movement towards the front. Cubist elements may be seen in the use of sharp outlines that emphasize fundamental geometric shapes and their grouping into a compressed plane, as well as the heavy layering of muted paint tones.

Although this vibrancy was quickly replaced by a serene steadiness, this early piece reveals essential formal characteristics that would occur throughout Morandi’s later works.

Natura Morta (Still Life) (1916)

| Date Completed | 1916 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 82 cm x 57 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York |

This still life is made up of two brown bottles, a gray pitcher, and coffee pot, and a two-toned gray box. The sculptures are simple and lack intricacy. They are placed on a beige tabletop, the border of which is slightly lower than the middle of the canvas, splitting it into three bands. The top and bottom bands are chocolate brown, emphasizing the tabletop, which is shown in a brighter tan to better distinguish the items and cast shadows.

Although this subject is uninteresting in and of itself, Morandi saw immense promise in it, stating that “even in as basic a subject, a great painter may accomplish a grandeur of perception and a strength of feeling to which we instantly respond.”

This would force Morandi to concentrate on the formal characteristics of line, color, and composition. Although simple, this piece must have held special significance for Morandi because it was hung on the wall of his studio for many years; he also chose this work to exhibit at the 1948 Venice Biennale.

Natura Morta (Still Life) (1918)

| Date Completed | 1918 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 30 cm x 30 cm |

| Current Location | Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome |

With three unidentified items floating in a box with a transparent front, this sculpture differs from his previous realism. This is one of a limited series of projects in which he drew inspiration from the Metaphysical style of art, and it shows the influence of renowned artists of this type, particularly Carlo Carra. While the three components appear to be a ball, a skittle pin, and a mitered frame edge, their placement is strange and rather unsettling. They float in the contained space of a box, which defies perspectival space as well.

Morandi shows the things in a well-ordered arrangement even while working in this illogical way.

The metaphysical components are secondary to the arrangement of the objects, the dynamism of the space around them, and how they reflect light; these characteristics are typical of Morandi’s larger body of work and outlive his experimenting at this stage of his career. According to art historians, Morandi initially experimented with adding deeper meanings to everyday items during this era of Metaphysical painting.

Morandi later distanced himself from this trend, noting that “my own works of that time remain pure still life creations and never indicate any philosophical, surrealist, mental, or literary concerns at all.”

Recommended Reading

This was a great introduction to Giorgio Morandi’s biography and artworks. If you want to find out even more about Morandi’s paintings, here is a book we can suggest. This can make for great additions to any bookshelf.

Giorgio Morandi (1998) by Karen Wilkin

This long-awaited book features the work of the reclusive, mysterious Bolognese painter and engraver. The essay follows Morandi’s various inspirations, from Cezanne to Giotto, and from Metaphysical artists to Cubists, and analyzes how his life and work have influenced critical interpretations of his art. Every stage of Morandi’s career is represented with a plethora of color reproductions, including his distinctive still lifes and landscapes with their peaceful groupings of muted items.

- Traces Morandi's many influences, from Giotto to Cézanne

- How his life and work have informed interpretations of his art

- Color reproductions illustrates every phase of Morandi's career

Giorgio Morandi’s subdued, introspective still lifes communicate an infinite variation within the groupings of ordinary things. The artist’s technique evolved from early experimentation with avant-garde movements like Futurism and Cubism into a distinctive painting style that favored small-scale paintings with simple reproductions of pots, bottles, dishes, and flowers. Close, multiple viewings show an incredible perceptual sophistication at work in the final compositions, which feel private, home, and serene.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Giorgio Morandi?

Giorgio Morandi was a well-known Italian artist who specialized in delicately tinted still-life paintings of ceramic containers. Morandi painted sun-kissed landscapes in both oil and watercolor, both from his studio window and outside in the Apennine hills. Paintings of the artist are frequently understood as a peaceful rejection of the turbulent modern world.

What Kind of Art Did Giorgio Morandi Create?

Giorgio Morandi’s paintings were based on simple and universal designs, but his painstaking paint application and attention to a specific Italian quality of light suggested an autobiographical element. Regardless of the fact that he depicted commonplace objects, critics observed how his portrayals of these objects reflected Morandi’s temperament, monastic routines, and Bolognese environment. His body of work would be significant for its careful analysis of everyday objects, infusing them with profound meaning by emphasizing their aesthetic beauty and simplicity.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Giorgio Morandi – The Life and Art of Italian Painter Giorgio Morandi.” Art in Context. May 20, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/giorgio-morandi/

Meyer, I. (2022, 20 May). Giorgio Morandi – The Life and Art of Italian Painter Giorgio Morandi. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/giorgio-morandi/

Meyer, Isabella. “Giorgio Morandi – The Life and Art of Italian Painter Giorgio Morandi.” Art in Context, May 20, 2022. https://artincontext.org/giorgio-morandi/.