African Art – Looking at African Artwork from Early Humankind to Today

African art is a continental and diasporic art. From east to west, north to south, the African cultures have been one of the most diverse in the world, considerably impacting the Western art world. Africa has long been considered the Cradle of Humankind, and it has seemingly been the heart of the world out of which emerged beautiful, diverse art. Many of us do not know where to begin with African art – this article will give an overview of African art, social and religious contexts, characteristics, and some of the prominent types of artworks and African artifacts.

Historical Context: The Cradle of Humankind

The Cradle of Humankind refers to an archaeological site in South Africa outside of the city of Johannesburg. What is significant about this site are the fossils and ancient tools found of early humans, also called hominins.

Some of the famous sites in the Gauteng provincial area in South Africa include the Sterkfontein Caves, among many others.

Various fossils were unearthed at the Sterkfontein Caves, importantly the skull of an early human that has been named “Mrs. Ples”, found by John T. Robinson and Robert Broom in 1947. The skull is estimated to be over two million years old, and while it was thought to be a woman at first, some scientists have speculated that it was a male.

The discovery in 1947 succeeded another important discovery in 1924, which was of another skull named the “Taung Child”. This was discovered by Raymond Dart in the North-Western town of Taung in South Africa.

There was also a skeleton named “Little Foot” that was also found in a Sterkfontein cave. It is estimated to be over three million years old, verging on almost four million, making it one of the oldest complete skeletons of an ancient hominid. Professor Ron Clarke, who pieced together this ancient ancestor, identified “her” as an Australopithecus prometheus species.

Fossils of an earlier species of hominids were also discovered at the Rising Star Cave system, which is also part of the Cradle of Humankind sites. The species were named the Homo naledi, believed to have existed over 200,000 years ago.

The First African Paintings

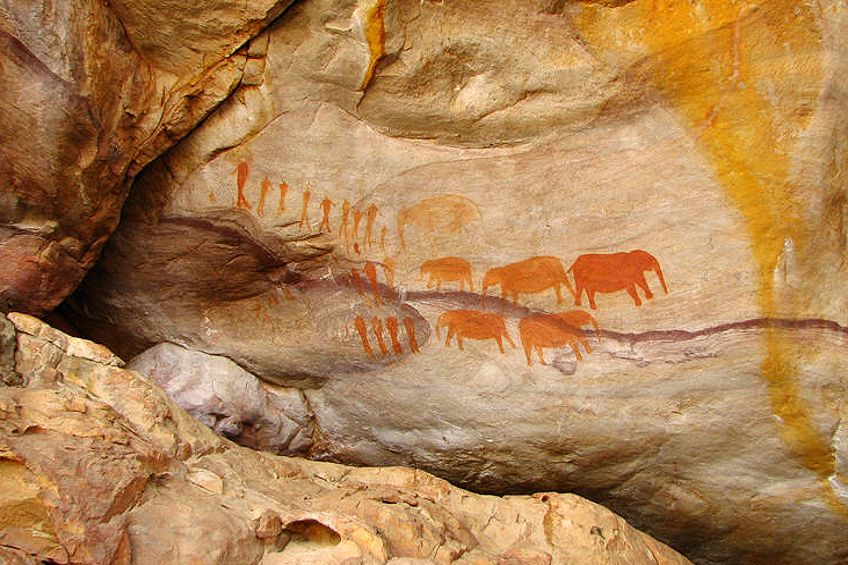

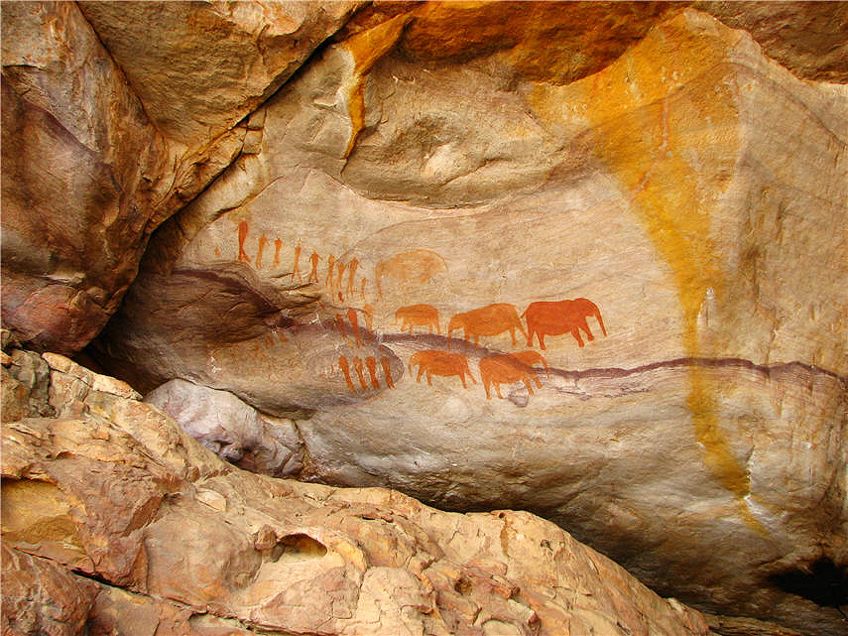

The prehistoric rock art of Africa is another discovery that gives us a peek at the rich world of ancient African art – we could also say these were the very first African “paintings” ever done. Suitable for an entire article on its own, rock art spans many locations in Africa. It was first created by the bushmen, the earliest indigenous inhabitants of Africa.

They were known as the San people, a hunting-gathering culture.

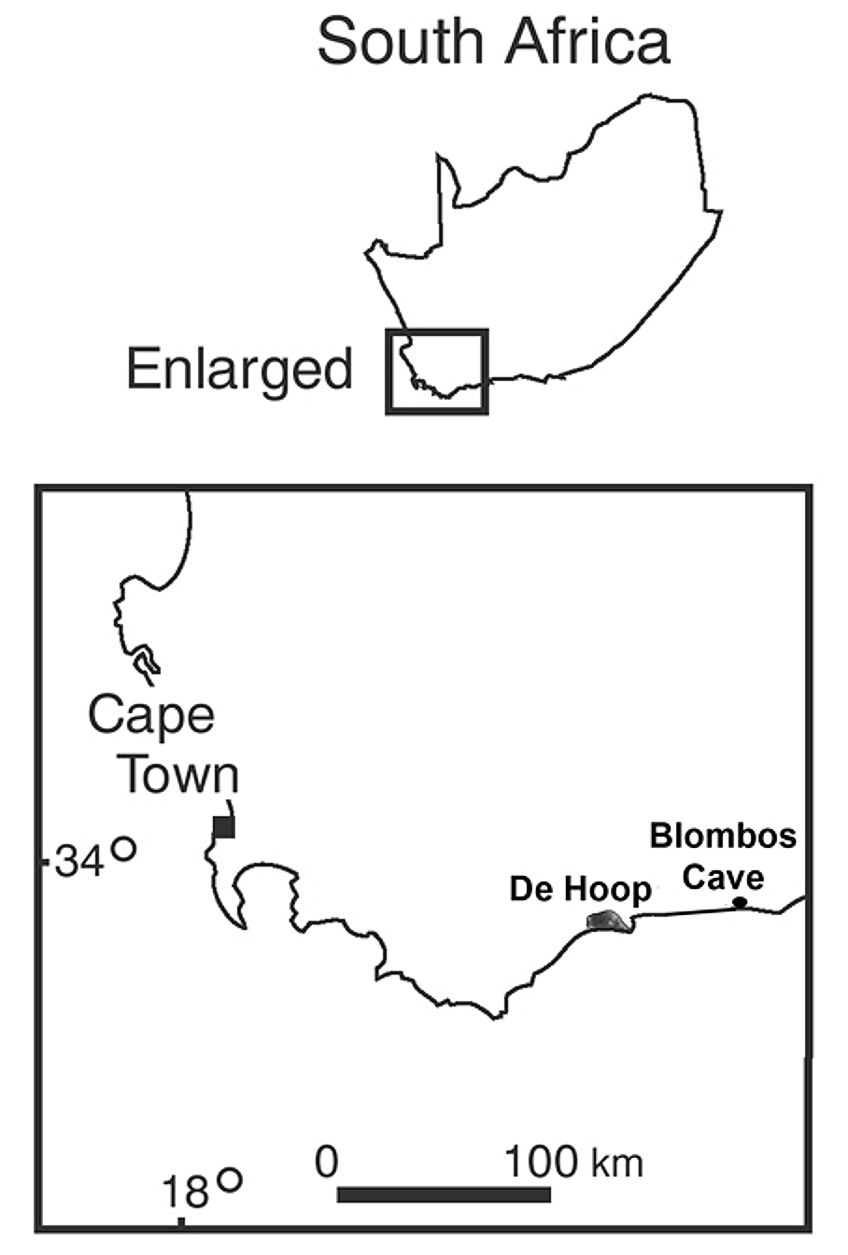

The San rock art is traced to various caves in Africa, some of which include the Blombos Cave in the Cape area of Southern Africa (estimated to be over 70, 000 years old), the Apollo 11 cave in Namibia, and various other caves in the Drakensberg area of Southern Africa.

Rock art depicted images of everyday life, animals, and numerous other images that have been understood as being symbolic in meaning. Overall, the San people have provided the world with painted panels of rock spaces, portraying their perspectives and experiences of life and the afterlife.

This was an important starting point for the development of African art.

Jumping a few thousand years after the hunter-gatherer lifestyle and rock paintings during the prehistoric times of Africa, we find ourselves with the first known West African artwork: sculptures from the Nok culture in Nigeria. This also suggests settlement by cultures using different tools and materials like ironworking.

The sculptures found were made from terracotta in animal and human shapes, and were dated from around 500 BCE to 200 BCE. Colonel Dent Young discovered the first terracotta sculpture in 1928 near a tin mine in the Jos Plateau, situated close to central Nigeria. A few years after this discovery, more sculptures were found (by accident) during mining.

Seven terracotta sculptures were found in Lydenburg, Mpumalanga in South Africa. These are called the Lydenburg Heads (c. 400 to 500 CE) because they are all in the shape of heads, some appearing helmet-like and one appearing animal-like. Two of the heads were also big enough to fit over a real head, while the remaining five were smaller. The purpose of these heads could have been for ceremonial or initiation rituals.

Understanding even a fraction of the historical significance of Africa as the heart of the world and “cradle” of humankind will give us more context in which to place African art, its lineage, diversity, and endurance over the ages.

Ancient African Artwork

From prehistoric caves to contemporary canvases, African art is rich and meaningful in so many ways. It would be impossible to condense all of it into one article, as there are so many facets that contribute to its existence. African art is also a concept created by the Western world in order to understand what possibly borders on African artifacts. With this, it is important for us to understand why what we know as “African art” existed in the first place.

Below, we will briefly explore some of the social and religious contexts of various regions in Africa where art was discovered. It is also important to note the variety of materials discovered, ranging from clay, metals (like bronze, brass, copper, silver, and gold), wood, ivory, and textiles like cotton and wool.

This section will also include various time periods, typically after the prehistoric times mentioned above, around the 1st century CE.

Social and Religious Context: What Does African Art Symbolize?

Apart from the aesthetic value inherent in African art, any type of object made served a purpose beyond the notion of “art for art’s sake”, as some sources indicate. Undoubtedly depending on the tribe and culture, African art links to ritual, religion, societal and moral values, rites of passage, kingdoms, hierarchy, and much more. It is the physical manifestation of the fabrics of cultural and ancestral makeups of each culture.

Larger Than Life: Religion and Ritual

Human figures were often portrayed with exaggerated features, veering away from a naturalistic representation. For example, the heads would be larger than the bodies. This was not done purposelessly, as some sources suggest many African cultures regarded the head as an important part in determining success in life.

Before Christianity and Islamic religions came to Africa, traditional religious practices and rituals were especially important aspects of many African cultures. The spirit or ancestral worlds played large roles and were accessed and venerated through “artistic” objects like sculptures, masks, statues, and various other objects.

Masks (usually made from wood and decorated with other materials) were worn to communicate or embody a deceased ancestor or deity. It would be worn during ceremonies like funerals, initiations, various celebrations, or for agricultural purposes like harvesting crops.

These ceremonies would involve dancing, where the mask wearer would go into a trance state while dancing, which would be an access point to connect with the spirits of ancestors.

When we look at sculptures and statues, we can see that these were utilized to venerate the spiritual world. They would be dedicated to deities or ancestors during rituals, and would also be utilized to embody spirits, otherwise referred to as “receptacles”. They were mostly in human and animal shapes.

Kingdoms and Villages

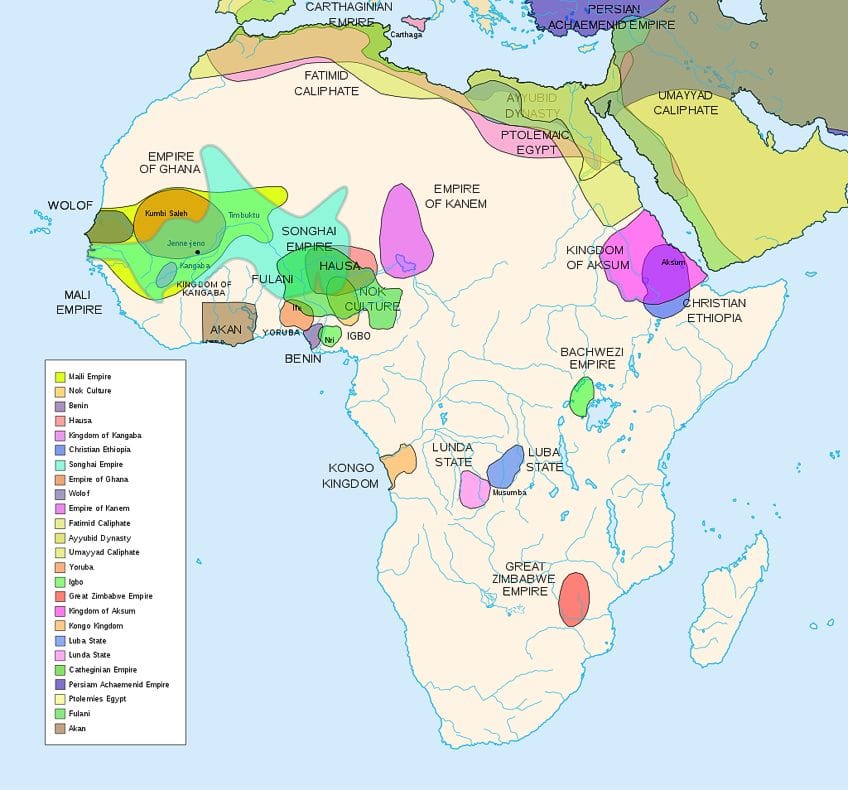

Apart from rituals and religious practices, when we look at traditional African cultures on a political and hierarchical level, we will understand the symbolism inherent in some of the artworks. Simply stated, before colonization occurred there were thousands of states that made up Africa. These were either large dynasties in the form of kingdoms or smaller village- and clan-based ruling structures. Kings (or leaders) were also highly venerated, often considered holy.

Artistic production was to convey the power and grandiosity of the king and kingdom. This ranged from metals, beads, and ivory in the forms of objects like flywhisks, pipes, clothing, staffs, and various other royal regalia. These objects were clear indications of the king’s status and rank within the societal structures. In villages, for example, artworks were utilized not so much to convey royal hierarchy but to teach the community about moral and social values, as well as to give a sense of embodiment to spiritual aspects of the culture as reminders of how to live.

These artworks would range from appearing more fearsome to venerating certain deities or mythical figures and honoring the importance of the natural world.

Furthermore, the objects were commissioned by elders or religious groups. Whereas in kingdoms, art was commissioned by those in charge and made specifically for royalty. In some kingdoms, for example, art objects were also used to control people and instill a sense of fear of the king or prince.

Praying for Rain: Farming and Crops

Farming was an undoubted large part of African culture and living off the land certainly gave communities a deeper reverence for the power of nature. In fact, with no rain, there would be no crops, and with too much rain, crops would die out. A plethora of other environmental and natural occurrences could threaten communities’ livelihood.

Masks have been used to symbolize the various stages of farming crops, from sowing, harvesting, weeding, to praying for rain or praying for less rain, as well as the fertility of soils. Some masks would also represent symbolic animals and deities associated with crops and harvesting.

The Stages of Life: Birth, Initiation, Death

Objects would be used for the stages of life, namely, birth, death, as well as various important initiations into adulthood for boys and girls, in order to assist with ceremonial processes. Some of the objects include sculptures, such as when women want to conceive.

Masks are often utilized during ceremoniess for rites of passage, especially for boys. These are to convey cultural values and moral messages, as well as to educate the boys about different aspects of manhood and life.

During funerals, masks are worn to celebrate the loved one or elder that has passed. Death is viewed as a passage or transition, and the ceremonies would often include celebrations as well as a period of mourning. The masks worn symbolized the deceased. Other objects like sculptures would also resemble the deceased in order to act as a vehicle to connect with ancestors.

African Art Characteristics

When we generalize African art, there are common characteristics inherent in masks, sculptures, and various stylistic portrayals of figures and animals. These suggested attributes give us information about African art’s aesthetics, as well as an easier ability to categorize it within the art world in relation to the religious, social, and political realms. We will briefly describe each one below.

The Human Figure

The human figure was an important feature in African art and sculptures would often resemble human figures, and through these figures, ideals about life or the spirit world would be expressed. If the sculptures were of animals, the animals would have some relation back to the human. They were utilized as symbols for humans or their traits; for example, an animal that represented strength or power would indicate the chief or king.

Smooth Surfaces

Objects like statues or sculptures would be delicately carved with smooth surfaces. These smooth surfaces would symbolize perfection and immaculate qualities, often described by the term “luminosity”. This would symbolize smooth, flawless skin, indicating beauty and good health.

Still and Dignified Posture and Expressions

When we look at many of the sculptures and statues of the human figure, we notice a stillness and almost emotionless expression in the figures’ facial features. This represented various qualities and character traits like self-composure, dignity, calmness, a controlled disposition, and restraint.

Sources indicate that this is to show collectedness when in more “public” situations, such as when someone is standing in front of a crowd during an initiation.

Mature and Youthful Appearance

Figures are usually depicted as youthful and healthy in appearance, almost at the height of their adulthood. This also indicates how both age and vigor were important and honored in the African cultures. This again suggested good health, fertility, as well as stature, and is referred to as the “ideal age”.

Composition: Balance, Symmetry, Abstraction

When we look at the overall composition of African artwork, or otherwise called African tribal art, there is a keen attention to creating a balanced and symmetrical figure. There was also attention to detail and the overall appearance of the object, where we notice a meticulous effort made by the craftsmen.

When it comes to abstraction in African artwork, there is also a veering away from complete naturalism.

We notice some figures appear in disproportion, even though, ironically, there is symmetry (as mentioned above) of the shape. Additionally, with overtly abstracted figures, there nevertheless remains a resemblance to the human figure or face.

We notice this abstraction in figures with larger heads than usual. Some figures have larger hands and feet, other figures have unnaturally long necks or torsos, and some generally have peculiar body stances. Other aspects of beauty (for example, the jewelry on their necks) or fertility would also be emphasized. For example, a woman’s body would appear with a large stomach or larger breasts.

Generic Physiognomy

Generic physiognomy refers to the practice where artists would utilize generic or set designs for facial features or heads, including the ears, eyes, nose, and mouth, or any other features. Not only would these be easier to replicate over time, but it was also used as a safeguard for the person in the event of personal attack or control through rituals like witchcraft.

Social Scale (Hierarchical Scale)

Social or hierarchical scale refers to the sizing of sculpted figures when there is more than one figure. The sizing indicates the figures’ place in the social system. For example, if the figure was more important, he would appear larger than the other figures (even if that figure was a child). Conversely, if the figure was not as important, he would appear smaller than the other figures.

The Regions of African Art

Now that we have a fundamental understanding of the “why” behind ancient African art, let us explore it further through regional glimpses. Below, we will discuss some of the African artwork from the different locations across the African continent. We will also briefly discuss contemporary African artwork, which differs from African tribal art, and has been a topic of debate among many scholars.

North Africa

Some of the countries that comprise North Africa are Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, and Sudan. Some of the art in Algeria includes the rock art in the region called Tassili n’Ajjer, housing thousands of rock art paintings. The paintings include depictions of animals and humans, as well as the famous “Round Head” figures.

Egyptian art is also part of the Northern African art category; however, it is such a diverse and broad art form that it is an entire topic on its own. This art also falls within the category of “Ancient Mediterranean” art.

When we explore the art of Sudan, where the Kush kingdom reigned, they produced famous ceramics from Kerma, which were around 2500 BCE to 1500 BCE. Some of the examples include the pottery by the artists known as the C-Group.

The Black Polished Incised Ware Cup (c. 1700 BCE to 1500 BCE) is an example where we notice the decorative incised markings on the outside of the cup, appearing in diamond shapes and done with the technique called “cross-hatching”. There are also “herringbone” patterns with bands in-between, separating each shape. Some sources suggest the patterns have been taken from basketry patterns.

South Africa

The countries that comprise Southern Africa include South Africa at the tip of the continent, with surrounding countries like Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Mozambique, Swaziland, and Zambia, among others. Some of the artwork in Southern Africa includes the rock art we explored above.

East Africa

East Africa is comprised of a collection of countries, including Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and various islands like Mauritius and Seychelles, among others. Countries like Ethiopia had a strong link to the Christian religion and produced sacred buildings like monasteries and churches.

Other artworks include various religious icons produced during the 15th Century.

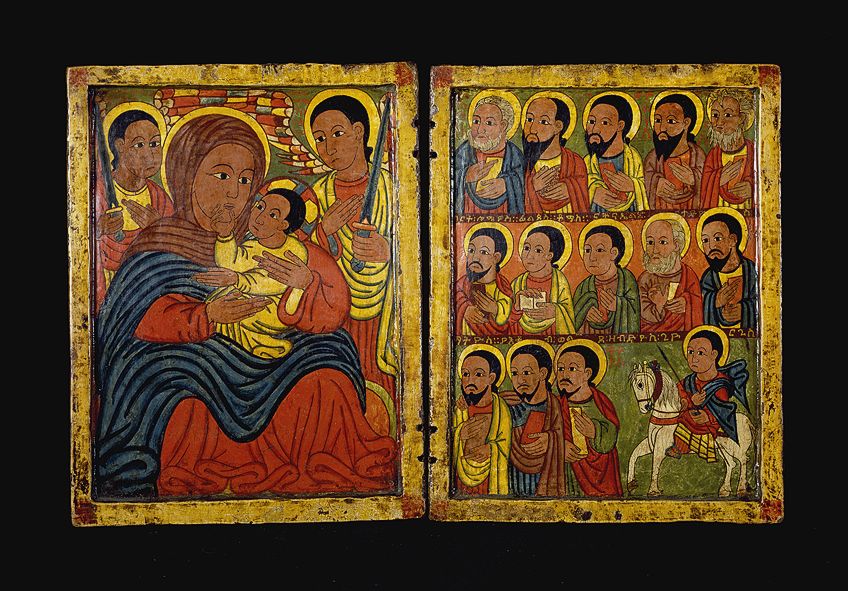

An example of a religious icon is one entitled, Diptych with Mary and Her Son Flanked by Archangels, Apostles, and a Saint (c. late 15th Century). The artist seems to be unknown, however many sources indicate that the artist was a follower of the monk Fre Seyon. Various Ethiopian icons appear with similar subject matter like the one mentioned here. These were made on wooden panels with tempera.

In the above diptych, we notice two images: the left depicts Mother Mary with the baby Jesus in her arms, holding on to her chin. Behind the figures are two angels gazing at the central figures. The right panel depicts a succession of 14 men, the Apostles, all gazing at the central figures to the left. One of the figures, in the bottom right corner, is on a horseback, suggested to be Saint George.

West Africa

The countries that make up West Africa include Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and many others. West African artwork spans many different cultures and modalities, including masks, pottery, jewelry, fabrics and textiles, and more.

We already met the Nok culture above, who created the terracotta masks.

Another famous West African culture includes Benin art, which came from the Kingdom of Benin in southern Nigeria. The dates are around 1440 to 1897 CE. Benin art is characterized by its bronze and brass sculptures, especially the brass plaques. These plaques were designed to adorn the king’s palace as well as to show off the king’s riches and splendor.

Some of the examples include the Brass plaque showing the Oba of Benin with attendants (c. 16th Century), Relief plaque showing two officials with raised swords (c. 1530 to 1570), Plaque depicting an audience hall (16 to 17thcentury), Relief plaque showing a crocodile with mudfish (c. 1530 to 1570), Relief plaque showing a dignitary with drum and two attendants striking gongs (c. 1530 to 1570). There were also ornaments, for example, the Leopard-head hip ornament (c. 16th to 19th Century), as well as the ivory mask, Queen Mother Idia (c. 16th Century).

Other Nigerian cultures include the Yoruba, who made a wide variety of masks. Other artwork included the famous heads cast in metals like copper and bronze in the city of Ife in Nigeria. The heads were discovered by accident in the Wunmonije Compound, totaling 17 heads. Some of the Yoruba artwork includes the Mask for Obalufon II (c. 1300 AD), Bronze Head from Ife (12th to 15thCentury), Mask with 7 birds (19th to 20th Century), Head of a king or dignitary (c. 12th to 15th Century AD), and Carnival Mask (c. 1950).

In addition to masks, the Yoruba made other structures like elaborate doorways, such as the door panels with lintels made by famous artist Olowe of Ise.

Central Africa

Central Africa includes countries like Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Republic of Congo, Gabo, Rwanda, and others. There have been a vast number of different artworks from Central Africa, each culture depicting the depth of their beliefs and kingdoms.

Some examples include the Fang people of Gabon, whose sculptures and masks are made meticulously and with a keen eye for detail. For example, the Reliquary Ensemble: Seated Female (c. 19th to 20th Century) is a carved female figure with a well-polished black exterior.

We notice exaggerated body shapes like the head of a child or infant and the body of an adult female. The muscles are well defined and to the point of bulging, and the figure’s facial expression is seemingly neutral, without too much expression. There are other types of versions of these statuettes, such as the Reliquary Guardian Figure (Mbulu Ngulu) (18th to 19th Century), which was used for the protection of bones from deceased family members.

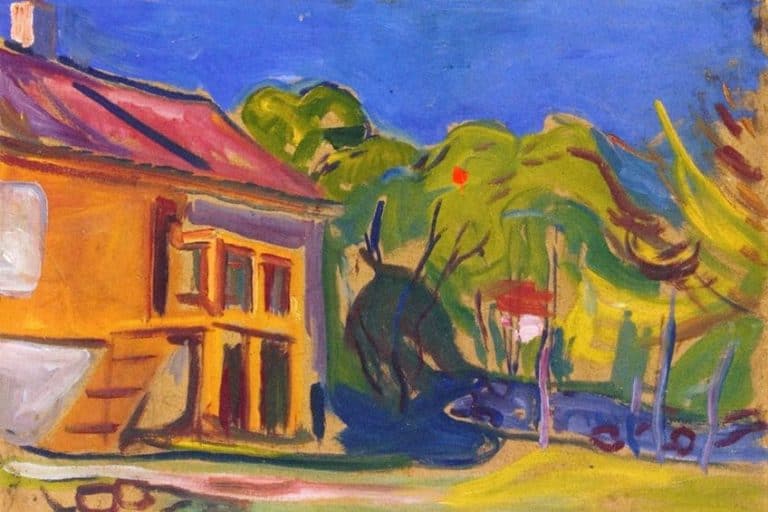

Contemporary African Artwork

Contemporary African art and the concept of this is a widely debated topic, with some sources suggesting that contemporary art in Africa started around the mid-1900s by various artists like Walter Battiss, Irma Stern, and many others. African tribal art has been an influence on many contemporary African artists.

There are various scholarly debates that attempt to define contemporary African art, some of which include different categories.

Some of the categories include Africa art based around tourism, otherwise known as “Airport art”, which provides a source of income for local artists. Other categories include art done from traditional styles, art made for the purposes of religion like Christianity, and the final category includes African art done from different styles and techniques verging on “rare” or “unknown”. These categories were proposed by the art historian Marshall W. Mount.

Other scholars also suggest different categories; for example, Valentin Y. Mudimbe, a French historian, suggested: “tradition”, “modernist”, and “popular” Africa art. There has also been a considerable theoretical base around the nature of Contemporary African art and what it means within the wider scope of the art world, historically and in modern times.

There are various words that draw distinctions between the meaning of African art (these are understood as dichotomies), such as its relationship between “art” and “craft”, the debate between “tradition” and “modern”, as well as the relationship between countries in Europe and Africa.

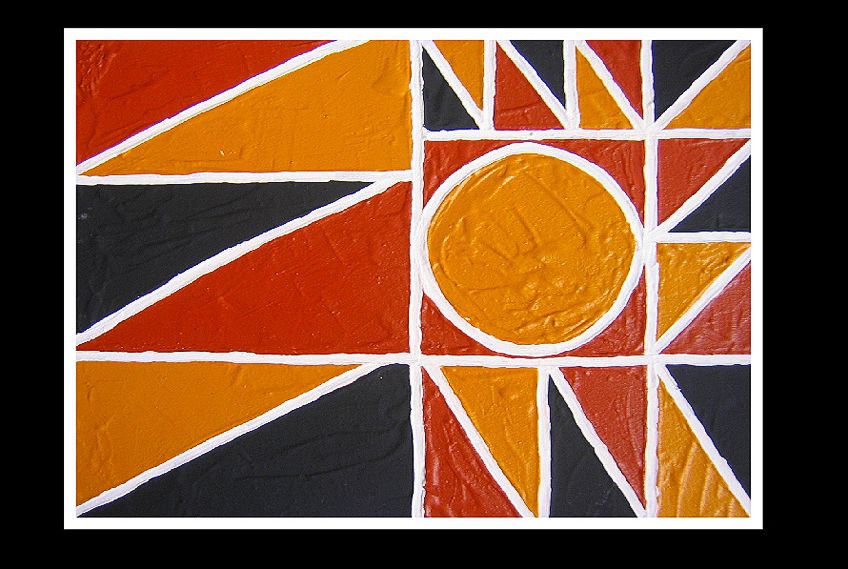

Contemporary African art is as diverse as African tribal art; there are many artists who also utilize different modalities and concepts.

Some artists are also internationally recognized and draw inspiration from traditional African art. It is a colorful and meaningful demonstration of the evolution of Africa art, its people, and the cultures that came before.

Africa and the World

African art is certainly continental, and its reach has gone far beyond the African continent, inspiring many other modern artists from the Western world. There have been many concepts underpinning what African art is and is not, not only in the microcosm of Africa but also in the macrocosm of the world.

After colonialism in Africa, African artifacts made their way into European institutions, as well as the minds and hearts of the Western world. But with this, there came a considerable debate about the nature of African tribal art, and the function – whether for aesthetics, politics or religion. However, what we must remember about African art is that although it has influenced the world, the world and its concepts have also influenced it.

Gaining a thorough understanding of each culture the African artworks originated from will create a fundamental understanding pertinent to the nature and life of African artifacts. This includes the life and times of African artists, who were significant parts and players to the evolution of this continental art, so to say.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is African Art?

African art is a concept the Western world created to understand what possibly borders on African artifacts. However, beyond this, African art spans the entire African continent. It is a rich culmination of different cultures from as early as prehistoric rock art, African tribal art, and contemporary African art. Each piece of African artwork serves a range of social, religious, political, or aesthetic-based purposes.

What Are the Characteristics of African Art?

African art characteristics comprise of several distinguishing factors, namely, the focus on the human figure, smooth surfaces, the appearance of being still and dignified in posture and facial expressions, depicting a mature and youthful appearance, along with the composition having a focus on balance, symmetry, and abstraction over a naturalism. There should also be Generic Physiognomy, which refers to the practice where artists would utilize generic designs for facial features or heads, and lastly, figures would be portrayed on a social scale or hierarchical scale.

What Does African Art Symbolize?

African art serves different purposes, and African artifacts were not only created for aesthetic purposes, which certainly also had their place. The creation of African art also related to other significant spheres of life such as ritual, religion, societal and moral values, rites of passage, kingdoms, hierarchy, and more. These spheres of life informed what art would be created and its functions.

Chrisél Attewell (b. 1994) is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. Her work is research-driven and experimental. Inspired by current socio-ecological concerns, Attewell’s work explores the nuances in people’s connection to the Earth, to other species, and to each other. She works with various mediums, including installation, sculpture, photography, and painting, and prefers natural materials, such as hemp canvas, oil paint, glass, clay, and stone.

She received her BAFA (Fine Arts, Cum Laude) from the University of Pretoria in 2016 and is currently pursuing her MA in Visual Arts at the University of Johannesburg. Her work has been represented locally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, residencies, and art fairs. Attewell was selected as a Sasol New Signatures finalist (2016, 2017) and a Top 100 finalist for the ABSA L’Atelier (2018). Attewell was selected as a 2018 recipient of the Young Female Residency Award, founded by Benon Lutaaya.

Her work was showcased at the 2019 and 2022 Contemporary Istanbul with Berman Contemporary and her latest solo exhibition, titled Sociogenesis: Resilience under Fire, curated by Els van Mourik, was exhibited in 2020 at Berman Contemporary in Johannesburg. Attewell also exhibited at the main section of the 2022 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Learn more about Chrisél Attwell and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Chrisél, Attewell, “African Art – Looking at African Artwork from Early Humankind to Today.” Art in Context. August 26, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/african-art/

Attewell, C. (2021, 26 August). African Art – Looking at African Artwork from Early Humankind to Today. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/african-art/

Attewell, Chrisél. “African Art – Looking at African Artwork from Early Humankind to Today.” Art in Context, August 26, 2021. https://artincontext.org/african-art/.