Ziggurat of Ur – The History of the Sumerian Ziggurat

The Sumerian Ziggurat of Ur was built in the 21st century BCE in what is today the Dhi Qar Province in Iraq. By the 6th century BCE, it had almost completely deteriorated, whereupon King Nabonidus ordered that it be restored. It is regarded as the most well-preserved example of Mesopotamia’s ziggurat buildings. In this article, we will look at the history of the Sumerian Ziggurat of Ur, and answer questions such as, “who built the Ziggurat of Ur, and what were Ziggurats made of?”.

The History of the Sumerian Ziggurat of Ur

| Architect | King Ur-Nammu |

| Date Completed | c. 2030 – 1980 BCE |

| Function | Ziggurat |

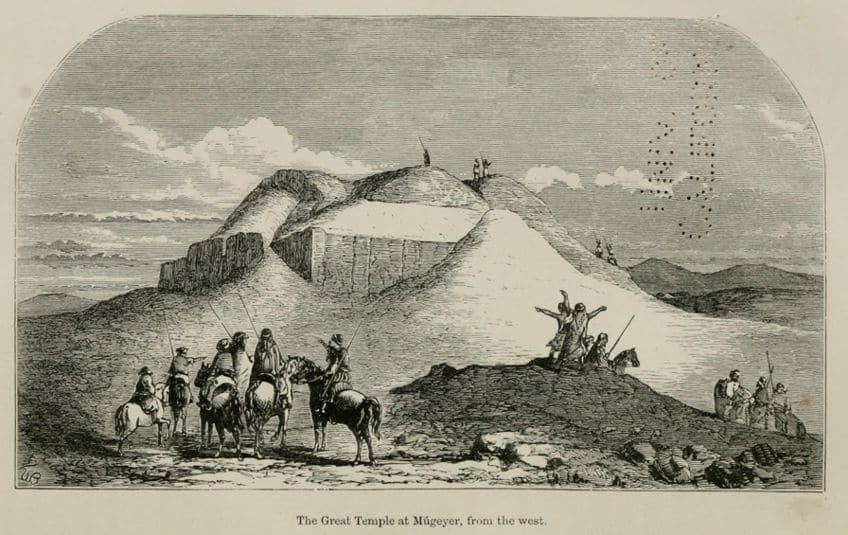

| Location | Tell el-Muqayyar, Dhi Qar Province, Iraq |

Most of the region that encompasses Syria and Iraq is a rather large and flat plain of cracked and dry mud, except for the area between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers known as Mesopotamia. Regarded as the cradle of civilization, it is where agriculture and writing first began to develop. It is where rural villages changed over time into cities, which themselves subsequently became kingdoms, and ultimately grew into powerful empires. However, unlike the relics of Greece and Egypt, most of what once stood has long since crumbled into ruins. This is no surprise, considering that this region flourished 2,000 years before Julius Caesar or Cleopatra even existed. Yet, as ancient as it is, by 2,000 BCE, the people of Sumeria had already created paved roads, laws, banking, writing, the vault and arch, educational institutes, and many other advancements in civilization.

What Are Ziggurat Buildings?

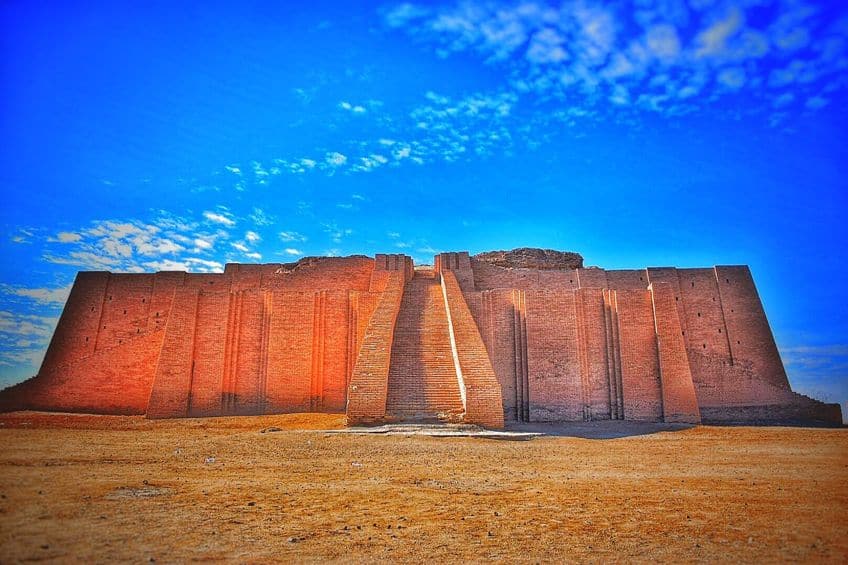

Ziggurat buildings are considered to be the Ancient Near East’s most distinct architectural structures. Similar in design to the pyramids of Egypt, these Ziggurat buildings had four sides and ascended to heights that seemed to aspire to reach the gods themselves. Yet, these Ziggurats differ from the pyramids due to the fact that they are tiered, which helped in the construction of the ziggurat buildings, as well as to conduct religious rites. Today, these ancient ziggurat buildings can still be found in present-day Iran and Iraq, and the most well-preserved and biggest example of these imposing structures is the Ziggurat of Ur.

These ziggurat buildings were constructed for the local religions of the Akkadians, Sumerians, Elamites, Babylonians, and Eblaites.

Every ziggurat building formed part of a larger temple complex that comprised several other buildings. Prior to the construction of ziggurats, simpler structures comprising raised platforms were built in the Ubaid period. They were also known for playing an astrological role, and some ziggurats were glazed in different colors on each side of the structure. These glazed bricks would sometimes be engraved with the names of the kings.

Ziggurat buildings were regarded as the dwelling place of the gods that they were dedicated to, therefore no public ceremonies were allowed to take place near the shrine, and only priests were allowed to enter the temple or any chambers at the base. They were considered to be very powerful figures within Sumerian society and were responsible for maintaining the house of the gods and seeing to their needs. For Mesopotamians, the temple was meant to bridge the heavens and the earth, and therefore, they were designed to reach into the sky. However, most Ziggurats contained between two and seven tiers.

Another function of these structures was that they offered a place for the priests to escape from the annual rising water levels that would occasionally cover the grounds for 100s of kilometers. The design also made the ziggurat buildings easy to protect and this prevented non-religious people or lower-ranking citizens from entering and disturbing the priest’s sacrifices and rituals. While some scholars state that the design of early step pyramids in Egypt were largely influenced by the design of the ziggurats in Mesopotamia, others feel that they were a development of the Egyptian mastaba tomb.

Construction of the Ziggurat of Ur

During the Third Dynasty of Ur (around the 21st century BCE) King Ur-Nammu ordered that the Ziggurat of Ur be built in dedication to the moon god Nanna. King Ur-Nammu is most remembered for his law codifications, regarded as one of human history’s first law codes, which served as the foundation for subsequent law codes – not only in the Mesopotamian region but well beyond. The Sumerian ziggurat measured over 30 meters in height, 64 meters in length, and 45 meters in width. As only the ziggurat’s original foundations still remained intact, the determined height is purely speculative.

Similar in function to a medieval castle spire, the ziggurat would have been located on the city’s highest point, and travelers, pilgrims, and the religious would have been able to see it from many miles away.

The structure at the top was viewed as an important site of reverence, as it served as the patron deity’s temple. However, the Sumerian ziggurat’s function was not just religious as it was also the place where the people of the city would bring their surplus agricultural stock for trading as well as pick up their allotted food parcels. Therefore, visiting the Ziggurat of Ur was for fulfilling both physical and religious needs. The temple was for many people the most significant element of the structure, however, it did not survive the ravages of time. Archeologists uncovered a few blue-glazed bricks on the site, which they think could have possibly been used for the temple’s decoration.

In Akkadian and Sumerian mythology, Nanna (also often called Sin) was the deity of the moon and was associated with fertility, agriculture, and wisdom. He was usually depicted as a wise old man with a beard, with the symbol of a crescent moon on his head. To further symbolize his connection to fertility and the moon, he is often portrayed riding a bull or clutching a scepter. He is sometimes also portrayed with his consort, the deity of the reed marshes, Ningal. The temple of Nanna was regarded as one of Sumeria’s most significant religious centers. It was also a place where they could study the motion of the moon. It is believed that the shrine was used to monitor the various moon phases, which was then used to develop the calendar.

It served not only as a shrine to Nanna but also as part of a larger complex that served as the city’s administrative center. King Shulgi completed the construction of the Sumerian ziggurat in the 21st century BCE, whereby he proclaimed that he was a god in an attempt to win the support of the surrounding cities. His reign lasted almost 50 years, during which Ur was developed to the point that it became Mesopotamia’s capital, controlling much of the region. It was the ideal location from which administrative government officials could carry out their work, as it was centrally positioned within the city.

The Ziggurat of Ur was used as the location from which to carry out several important administrative functions of the city. This includes record-keeping, as it housed all of the city’s important records, such as its trade agreements, taxes, and laws. Due to its central location, it was the perfect place from which collectors could collect the residents of the city’s taxes. It was also a place where government officials could be approached to resolve certain disputes, as well as a trading hub where merchants would bring their wares to exchange goods.

What were ziggurats made of, though? The majority of ziggurat buildings were constructed from stacked bricks made from mud, which were sealed also using mud.

Despite being a rather primitive-sounding building material, the construction of the ziggurat displays incredible design and engineering details. For example, based on the season, the non-baked brick core can often get damp. To allow for evaporation to occur, the builders had included holes in the exterior layer. They had also incorporated drains into the terraces so that the winter rains could be drained away. In the 6th century BCE, King Nabonidus reconstructed parts of the Ziggurat of Ur. There was not much left of the structure to provide any clues as to the structure’s original appearance. He restored the temple at the top of the ziggurat and helped transform Mesopotamia into one of the region’s most important religious centers.

Modern Excavation and Preservation of the Ziggurat of Ur

In 1850, British explorer and archeologist William Loftus discovered the ziggurat’s remains. John George Taylor then proceeded to excavate the site, leading to the conclusion that it was the ancient city of Ur. Henry Hall and Reginald Campbell conducted preliminary excavations following the conclusion of the first World War. From 1922 to 1934, the site was then extensively excavated by Sir Leonard Woolley, in a collaborative project with the British Museum and the museum of the University of Pennsylvania. Woolley uncovered a large pyramid-like structure, facing true north, and designed with multi-level terraces.

The first terrace was accessed by ascending one of three large staircases. From there, the second terrace could be reached by ascending a single staircase. On top of the second terrace was a large platform on which a temple had been built which contained the uppermost terrace. Mud bricks were used to form the core of the structure, and were then surrounded by baked bricks which had been joined using a natural tar called bitumen. Around 720,000 baked mud bricks were required to build the lowest part of the structure that supports the first terrace.

Therefore, the resources required to construct the entire ziggurat must have been staggering. Today, the ziggurat’s lowest layer is the only remains of the original period of construction. The Neo-Babylonian restorations were responsible for the reconstruction of the following two layers. The lowest level’s facade, as well as the large staircases that lead to the second level, were reconstructed by the orders of Saddam Hussein. Unfortunately, since that last renovation effort, it has experienced a bit of damage due to wars in the region.

Hoping that the American and coalition forces would not bomb the site as it contained a historic monument, Hussein had all of his fighter jets parked right next to the Ziggurat of Ur in 1991.

Yet, despite not being directly hit, the region was bombarded and the ziggurat was shelled with small arms fire, resulting in some damage to the structure. Today, there are still four clearly visible craters that are the result of bombs that were dropped near the Ziggurat of Ur. There are also more than 400 bullet holes visible in the walls of the ziggurat.

Visiting the Ziggurat of Ur

The Ziggurat of Ur is open for tourists to visit. However, since it is situated in a notoriously war-torn region of southern Iraq, access to the ziggurat may be drastically restricted owing to concerns over security. It is advised that before making any plans for visiting the Ziggurat of Ur, or any other ziggurat buildings, first contact your travel agencies as well as the local authorities for guidance and up-to-date information regarding accessibility. It has also been many decades since there has been any reconstructive work on the site, and it is not as well-preserved as many of the other ancient sites that tourists frequent across the world, so one should not go with high expectations, or hope to see the structure in anything close to its original design. However, if you manage to go at the right time, simply to enjoy the historical value of these ancient buildings, you will be enriched by the experience.

Situated in present-day Iraq, the Ziggurat of Ur was among ancient Mesopotamia’s most significant centers of administration, trade, and religion. Dedicated to Nanna, the Sumerian and Akkadian god of the moon, it was constructed from mud bricks and bitumen and was one of the ancient world’s largest structures at around 50 meters in height. The temple to Nanna at the top of the ziggurat was accessible by a system of staircases and ramps, which divided the structure into terraced layers – a style that distinguishes it from other pyramid-shaped structures such as those found in Egypt. Over the centuries, the Ziggurat of Ur was destroyed and reconstructed several times in an attempt to restore the important structure to its former glory. However, since only the original foundations remained, much of the reconstruction work has been designed through educated guesses and accumulated data. This data was sourced from various studies that tried to determine the original design based on environmental information and historical written sources.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are Ziggurat Buildings?

Constructed during the third millennium BCE in Mesopotamia, ziggurats were large pyramid-like structures that were built from sun-baked and fire-baked bricks. They were designed to have multiple levels, which were accessible through a complex system of staircases and ramps. At the top of the Ziggurats were small temples that were dedicated to the various patron gods of the region. These were exclusively for the use of the priests.

What Function Did Ziggurat Buildings Play?

Ziggurat buildings were multi-functional and served several roles for the citizens of Mesopotamia. They were important places of worship, and they could be seen from miles away, so they acted as beacons for traders, merchants, travelers, and pilgrims. They were also centers of civil administration, where important documents were stored, such as tax records, trade records, and the various law codes that the Sumerians pioneered. They also served an astrological function, as the platforms were used to keep a record of the movements of the moon. This information was used to develop their calendar system. Merchants and traders would also use the space to conduct their business, and citizens would come from rural areas far away to trade their surplus agricultural stock.

What Were Ziggurats Made Of?

As one can imagine, in such a vast, dry, and flat terrain, there was not much in the choice of available building materials. One thing there was plenty of, though, was mud. And the Sumerians knew exactly how to build with mud, making sun-baked bricks for the foundation and center, and using fire-baked bricks for the rest. They would start with a foundation and then build the various tiers, each tier built on the platform roof of the tier underneath it. The higher that they could build, the better it was seen, as ziggurat buildings were meant to act as a bridge between this world and the heavenly realm.

Who Built the Ziggurat of Ur?

The Sumerian King Ur-Namma was the person who first ordered the structure to be built. Construction first started in the 21st century BCE. However, in the centuries that followed, the structure almost completely deteriorated, with nothing remaining except for the original platform. King Nabonidus then undertook an extensive project to reconstruct the ziggurat in the 6th century BCE. The last person to undertake any major reconstructive efforts was Saddam Hussein in the early 1990s. He ordered that the facade be reconstructed, as well as the three main staircases that ascend the building to be rebuilt. However, the building sustained a bit of damage during the war that followed with the Americans and their allies.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Ziggurat of Ur – The History of the Sumerian Ziggurat.” Art in Context. June 28, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/ziggurat-of-ur/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 28 June). Ziggurat of Ur – The History of the Sumerian Ziggurat. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/ziggurat-of-ur/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Ziggurat of Ur – The History of the Sumerian Ziggurat.” Art in Context, June 28, 2023. https://artincontext.org/ziggurat-of-ur/.