Tamara de Lempicka – Exploring the Life and Art of Tamara de Lempicka

Tamara de Lempicka’s artworks were inspired by dramatically varying sources. Paintings such as her 1925 Group of Four Nudes and Kizette in Pink displayed her adoration for the Italian Renaissance style as well as the Avant-Garde and Art Deco styles. She was the only conventional easel artist producing works in the Art Deco genre.

The Life and Art of Tamara de Lempicka

The “Roaring Twenties” was a period of tremendous political and social transformation in both the United States and Europe. Many women enjoyed emancipation with rapid socioeconomic expansion and a thriving consumerism lifestyle. Women could now vote in elections, and many of them went to gain employment and were more economically autonomous. This sudden independence manifested itself in how they appeared and acted.

The “flapper”, a woman who wore free-fitting clothes, had a shorter, bobbed hairstyle, and lived a carefree life, is a hallmark of the period that many people now may recall.

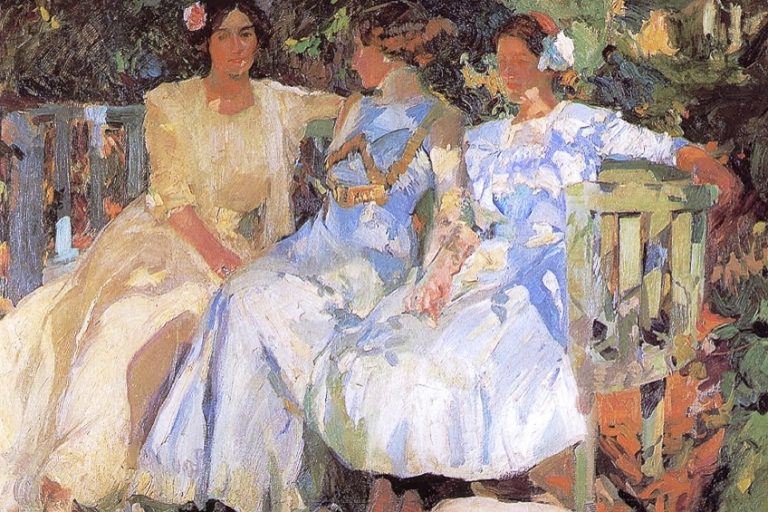

These are the ladies who influenced Polish artist Tamara de Lempicka’s artworks. She was known as “The Lady with a Paintbrush” for her self-portraits and portraits of ladies in her stylish, Art Deco genre. Her refined Art Deco portraits of nobles and the affluent, as well as her highly stylized portraits of the nude, are among her most well-known works. Her elegant work exudes female strength and passion, and it honors the individuality and liberty of females in the 1920s.

“I spend life on the fringes of civilization,” Lempicka famously observed, “and the norms of regular society do not pertain to people who exist on the perimeter.”

The Early Years of Tamara de Lempicka

Tamara de Lempicka was born in Warsaw on May 16, 1898, which was at that time part of the Russian Empire’s Congress Poland. Her father, Boris Gurwik-Górski, was a Jewish Russian lawyer for a French trade corporation, and her mother, Malwina Dekler, was a Polish aristocrat who had spent the majority of her life overseas and met her spouse at one of Europe’s resorts.

Her mother ordered a pastel painting of her when she was ten years old from a well-known neighborhood painter. She despised modeling and was unsatisfied with the final product. She grabbed the pastels, put her little sister in a pose, and created her first portrait. Her family sent de Lempicka to a boarding house in Switzerland, in 1911, however she was unhappy and faked illnesses to be allowed to depart.

Her grandmother instead took her on a trip to Italy, where she acquired a passion for art.

After her parents separated in 1912, she opted to spend the summer in Saint Petersburg with her rich Aunt Stefa. In 1915, she encountered and had a romantic relationship with Tadeusz Lempicki, a distinguished Polish attorney. Her family provided him a hefty dowry, and they wedded in St. Petersburg in 1916. Their privileged existence was upended by the Russian Revolution in November 1917.

Tadeusz was detained in the dead of night by the intelligence service, in December 1917. Tamara scoured the jails for him and obtained his parole with the aid of the Swedish consul, to whom she had given her favors. They moved from Copenhagen to London, and eventually to France, where Tamara’s relatives had sought safety as well.

The Story of Tamara de Lempicka’s Artworks

For a while in Paris, the Lempicka’s subsisted on the selling of family gems. Tadeusz was hesitant or incapable of locating acceptable employment. Their child, Maria Krystyna “Kizette”, was born in 1919, which added to their monetary difficulties. At her sister’s recommendation, Lempicka chose to become an artist and attended the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts with André Lhote and Maurice Denis who would have a stronger effect on her technique. Her early works were portraits of her child Kizette and as well as still lives.

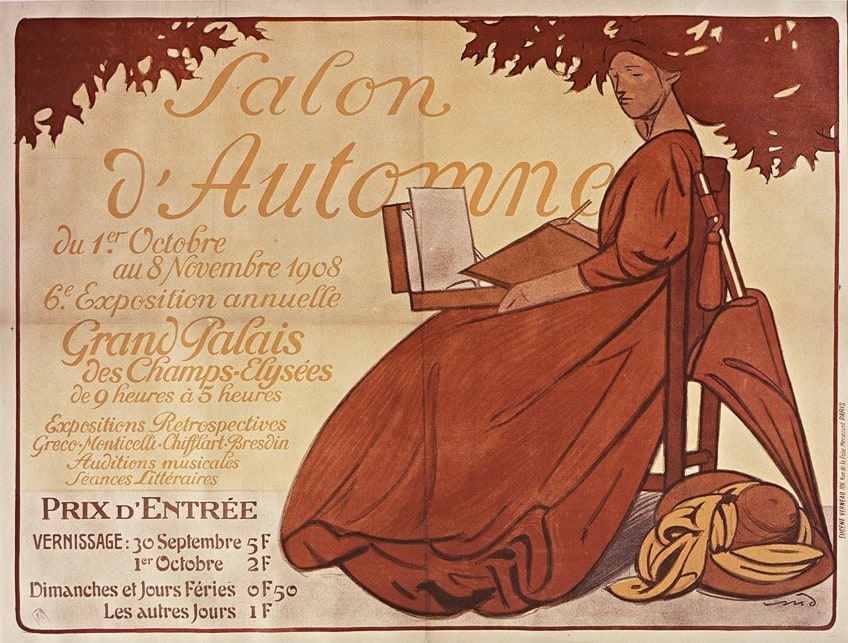

The first of Tamara de Lempicka’s artworks were sold through the Galerie Colette-Weil, allowing her to participate in the Salon des indépendents, an exhibition for potential new artists. In 1922, she made her debut appearance at the Salon d’Automne.

Her big break occurred in 1925, with the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, which was responsible for the rise of the Art Deco movement. Her artworks were shown in two important locations, the Salon des Femmes Peintres and the Salon des Tuileries. Tamara de Lempicka’s paintings were discovered by American fashion editors from Harper’s Bazaar and other publications, and her fame started to spread.

That same year, Count Emmanuele Castelbarco arranged her debut big exhibition in Milan, Italy.

In six months, Lempicka created 28 new pieces for this exhibition. During her journey in Italy, she met a new suitor, Marquis Sommi Picenardi. She was also asked to meet Gabriele d’Annunzio, a well-known playwright and poet from Italy. She paid him two visits to his estate on Lake Garda, hoping to create his picture; he, on the other hand, was intent on romance. She left unhappy after her futile efforts to obtain the contract, while d’Annunzio remained disappointed. Lempicka earned first place at the Exposition in Bordeaux in 1927 for her painting, Kizette on the Balcony.

Her marriage to Tadeusz Empicki ended in separation in 1928. The next year, she dated Raoul Kuffner, a nobleman and art collector. His rank was not old; it had been bestowed to his family by Franz-Joseph I because Kuffner’s family had supplied the imperial court with meat and alcohol. He had a large number of properties throughout Eastern Europe.

He hired her to create a portrait of his lover, Nana de Herrera, the dancer from Spain. Lempicka completed the painting (which was not complimentary to de Herrera) and replaced her as the baron’s lover. She purchased a property on Paris’s Rue Méchain and had it furnished by Robert Mallet-Stevens, the modernist architect, and her sister Adrienne de Montaut. Rene Herbst designed the furnishings.

The efficient, minimalist rooms were featured in design journals.

Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti), one of the most well-known Tamara de Lempicka paintings, was created for the front of the German fashion and style publication Die Dame in 1929. This depicted her driving a Bugatti sports vehicle while donning leather headgear, mittens, and a grayish scarf, a depiction of chilly elegance, individualism, luxury, and unavailability. She did not, in fact, possess a Bugatti; her car was a little yellow Renault that was snatched one night while she and her companions were partying at La Rotonde in Montparnasse.

She visited America in 1929 for the first time to create a portrait of US oil baron Rufus T. Bush’s fiancée and to organize a display of her paintings at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh. The exhibition was a smash, but the money she gained was wasted when the bank she used failed in the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash. The painting of Rufus T. Bush’s fiancée, Joan Jeffrey, was finished but stored following the couple’s separation in 1932. After Joan’s death in 2004, it was auctioned by Christie’s. During the 1930s, Lempicka’s career peaked.

She produced portraits of Greece’s Queen Elizabeth and Spain’s King Alfonso XIII.

Tamara Lempicka’s paintings started to be collected by museums. She journeyed to Chicago in 1933, whereupon her photographs were displayed beside those of Georgia O’Keeffe, Willem de Kooning, and Santiago Martnez Delgado. Throughout the Great Depression, she managed to get contracts and exhibit her works in a number of Parisian galleries. Baron Kuffner’s wife passed away in 1933. De Lempicka wedded him in Zurich on February 3, 1934. She was concerned about the rise of the Nazis and convinced her spouse to liquidate most of his assets in Hungary and relocate his wealth and possessions to Switzerland.

Tamara Lempicka’s Period in the United States and Mexico

Following the onset of World War II in the winter of 1939, Lempicka and her spouse relocated to the United States. They originally settled in Los Angeles. The Paul Reinhard Gallery planned a display of her paintings, and they relocated to Beverly Hills, taking up residence in the old home of film director King Vidor. Her art was shown at the Courvoisier Galleries in San Francisco, the Julian Levy Gallery in New York, and the Milwaukee Institute of Art, but her exhibitions were not as successful as she had intended. In 1941, her child, Kizette, managed to flee occupied France through Lisbon and join them in Los Angeles. Kizette then married Harold Foxhall, a Texan geologist. Tamara de Lempicka then moved to New York City in 1943.

She maintained a frantic social lifestyle in the postwar period, although she received fewer contracts for society portraiture.

In the midst of postwar abstract expressionism, her art deco flair appeared out of place. She broadened her topics to include still lifes, and in 1960 she started to create abstract pieces using a palette knife rather than her earlier fluid brushwork. She occasionally modified older paintings in her new manner. The sharp and straight Amethyste (1946) was transformed into the pink and fluffy Girl with Guitar (1963). In May and June 1961, she held an exhibit at the Ror Volmar Gallery in Paris, but it did not rekindle her past popularity.

Her husband died of a heart attack on the Liberté ocean liner on the way to New York in November 1961. Following his death, Lempicka sold much of her assets and set off on three round-the-world voyages. Lempicka withdrew from her career as a professional painter in 1963 when she relocated to Houston, Texas, to live with Kizette and her family.

She kept repainting her previous paintings.

She recreated her famous Autoportrait twice; Autoportrait III was purchased, while Autoportrait II remained in her senior apartments until her passing. Her final piece was the fourth version of her depiction of St. Anthony. She opted to go to Cuernavaca, Mexico, in 1974. Kizette relocated to Cuernavaca after her spouse died in 1979 to care for de Lempicka, whose health was deteriorating. On March 18, 1980, Tamara de Lempicka passed away peacefully in her sleep. Her remains were spread over the volcano Popocatépetl, as she had requested.

The Rediscovery of Tamara de Lempicka’s Artworks

In the late 1960s, there was a rebirth of popularity in Art Deco. In the summer of 1972, a tribute of de Lempicka’s works was staged at the Luxembourg Gallery in Paris, which got good reviews. Her earlier Art Deco works were seen and acquired again after her passing.

A theater play influenced by her encounter with Gabriele D’Annunzio was initially presented in Toronto.

It then played in Los Angeles for 11 years from 1984 until 1995 at the Hollywood American Legion Post 43, marking it the city’s oldest continuous play with 240 performers engaged over the decades. The drama was later staged in New York City in the Seventh Regiment Armory. Kara Wilson, an actor, and painter staged Deco Diva, a one-woman theatrical production inspired by Lempicka’s life, in 2005. Ellis Avery’s novel The Last Nude (2012), winner of the Barbara Gittings Literature Award in 2013, fictionalized her biography and her romance with one of her subjects.

The Scandals Surrounding the Artist

Lempicka was a bisexual person. Her relationships with both males and females were carried out in what was regarded as scandalous ways during that era. In her portraits, she frequently incorporated technical and storytelling aspects, while her nude paintings explored themes of yearning and sensuality.

In the 1920s, she became closely connected to bisexuality in literary and cultural groups.

Her spouse separated from her in 1928 because of her “sensational” behavior. Kizette, Lempicka’s only daughter, was placed in the custody of her grandmother. Amidst this, her daughter was memorialized in a number of her mother’s paintings, including Kizette in Pink, and Baroness Kizette.

The Subjects and Style of Tamara de Lempicka’s Artworks

“I was the very first female to do clear portraits,” Lempicka later told her child, “and it was the root of my popularity. Between a hundred paintings, my work was always distinguishable. Since my images drew a lot of attention, galleries tended to display them in the nicest spaces. My job was straightforward and completed. I looked around and saw nothing but absolute devastation of paintwork. I was disgusted by the mediocrity into which art had devolved. I was looking for a skill that no longer existed, so I worked fast and delicately with a brush. I was looking for a method, craftsmanship, minimalism, and fine taste. My objective is to never imitate. Create a fresh look with vivid and vivid hues, and recapture my characters’ grace.”

She was among the most well-known Art Deco artists, with Diego Rivera, Josep Maria Sert, Rockwell Kent, Reginald Marsh, and Rockwell Kent. But unlike these painters, who sometimes created vast murals with multitudes of figures, Tamara de Lempicka concentrated almost entirely on portraiture.

Maurice Denis, her first instructor at the Academie Ranson, gave her the famous maxim: “Notice that a work before it becomes a horse, a naked lady, or any narrative, is fundamentally a flat area covered with pigments put in a precise arrangement.” He was mostly a decorative painter who trained her in classical painting techniques. André Lhote was another key instructor, teaching her to pursue a gentler, more polished type of cubism that would not shock the observer or appear out of place in a beautiful living room. Her cubism differed greatly from that of Georges Braque or Pablo Picasso, who she felt “embodied the freshness of devastation.

Lempicka mixed neoclassical style with softer cubism heavily influenced by Ingres, notably his renowned Turkish Bath, with its exaggerated figures dominating the canvas. Ingres had a strong effect on her work La Belle Rafaela. Following Ingres, Lempicka’s approach was clear, exact, and exquisite, but it was also imbued with passion and a hint of depravity. Her cubist components were frequently in the backdrop of her works, behind the Ingresque characters.

Her works were dominated by flawless skin texturing and equally flawless, dazzling clothing materials. She was most known for her pictures of affluent nobles, but she also produced highly stylized nude artworks. The nudists are almost always women, whether represented singly or in groups; one of her rare male nudists appears in Adam and Eve (1931). After her Art Deco portraits went out of vogue in the mid-1930s, and “a major spiritual crisis, mixed with a deep despair amid an economic collapse, triggered a fundamental transformation in her work,” she began producing less whimsical subject matter in the same manner.

She produced Madonnas and turbaned ladies influenced by Renaissance art, as well as melancholy topics like The Mother Superior (1935), a portrait of a nun with a teardrop flowing down her face, and Escape (1940), which illustrates immigrants. “The baroness’s more ‘righteous’ themes are, it must be stated, weak in conviction when contrasted with the clever and gallant works on which her prior renown had been established,” art historian Gilles Néret commented. Surrealist themes were incorporated by Lempicka in artworks such as Surrealist Hand and in several of her still lifes.

Between 1953 until the early 1960s, Lempicka created hard-edged abstracts that resembled 1920s Purism. Her most recent pieces, produced in warm tones using a palette knife, are often regarded as her least effective.

Tamara de Lempicka’s Artistic Legacy

Tamara de Lempicka created a new picture of the contemporary woman in both her lifestyle and her paintings: partly jazz-age female, hedonistic and societal climber, and partly shrewd promoter, self-styled innovative painter, and insightful historical and cultural forecaster. In many respects, Lempicka’s creative oeuvre has been regarded as inextricably linked to her larger-than-life persona and, more importantly, her sexuality.

Her art, while probably Cubist-inspired to some degree, oozes the opulence of the ornamental, as do her subjects.

Tamara de Lempicka’s artworks have been a motivation to characters as varied as vocalist and creator Florence Welch and fashion designers Louis Vuitton and Karl Lagerfeld. She found her specialty – a pleasant position between classical easel artwork influenced by the likes of Ingres and items created exclusively for decorative purposes.

The Noted Accomplishments of Tamara de Lempicka

Despite being taught by two prominent avant-garde painters at the peak of post-Cubist exploration, Tamara de Lempicka’s paintings are most generally classified as Art Deco. Although her work contains Cubism’s geometric, multifaceted shapes, her concentration on soft contouring created a more sensual impact. Her sitters’ figures are somewhat deformed, making them look like lovely objects and human characters.

She used Deco’s rich, restricted palette – notably graphic design – to produce glossy portraiture that was more ornamental than real high art.

For feminist artistic scholars, Lempicka’s behavior, in which she flaunted her promiscuous liberty, has been a source of consternation. Because she regularly represented her feminine partners as well as other females – often in couples or groups – as delighting in their sensuality in front of a female artist, Lempicka can be seen as a form of proto-feminist.

Indeed, as a female artist depicting the feminine nude, she defied the traditional structure in which a nude person is shown only for the male’s viewing enjoyment. As a consequence, there is a type of egalitarian exhibitionism. The exception may be that, as a representative of the higher class, Lempicka’s independence was easier to get and pardon.

Her sensuous images’ shining surfaces are homages to jazz- and flapper-age extravagance after the terrible suffering of wartime.

She was a favored painter of the affluent and celebrities of her period, and her appeal remains to this day with stars like Jack Nicholson, Madonna, and Barbra Streisand. These celebrities were said to appreciate her clear edges and strong pronouncements from a past era. Lempicka’s works were featured in several of Madonna’s music videos including Vogue in 1990 and Express Yourself in 1989.

Important Tamara de Lempicka Paintings

Most of Tamara de Lempicka’s artworks were portraits of aristocrats. These artworks were produced in the Art Deco style. Here is a list of some of her most important artworks:

- Group of Four Nudes (1925)

- Self Portrait in the Green Bugatti (1929)

- Kizette in Pink (1926)

- The Musician (1929)

- Sleeping Girl (1930)

Interesting Facts About Tamara de Lempicka

Tamara de Lempicka lived an extraordinary and fascinating life, the experiences from which fuelled her artworks and paintings. You may think you know everything there is to know about Tamara de Lempicka by now, but here are a few more interesting facts about this notoriously provocative and talented Art Deco artist.

De Lempicka Was a Painter of the Fascist Ideology of the “Super World”

In fact, de Lempicka’s portraits were associated with the “call to order” ideology, a revival of monumental realism in the art of Europe. Her work emanates the gloomy and questionable beauty of totalitarian control. When she depicts the Duchesse de la Salle, she is wearing jackboots and has one hand put into her pocket in a menacing pose. It’s a fantastic image, done with the pure theatrical delight and impeccable sense of design that characterizes De Lempicka’s greatest works.

De Lempicka Was a Sporadic Artist

Scholars note that her arrogance, like that of many unscrupulous individuals, might have given way to a spirit of horrible daftness: cubism and kitschy. Tamara lost her way once she was elevated to the position of Baroness Kuffner. The desire for fame, and perhaps for survival, had passed her by. The art deco era, in which she excelled, had come to an end. After the acerbic forthrightness of her painting of lesbian nightclub owner Suzy Solidor, her tender studies of old men with instruments and sententious mother superiors were regarded as a terrible anti-climax.

Females Are Feisty, Assertive in Tamara de Lempicka’s Universe

Her extremely collectible artworks are now powerful emblems of a past era, portraying the sensual splendor and indulgence of the 1920s with gorgeous ladies set against exaggerated Modernist landscapes. She was a revolutionary proto-feminist who challenged the traditional portrayal of females as meek and docile, portraying women from a feminine viewpoint as formidable individuals in command of their own bodies and thoughts.

Her aesthetic was as avant-garde as its substance, fusing Cubism, Art Deco, and Futurism, establishing her as a profoundly important pioneer.

Recommended Reading

If you have been searching for books about Tamara de Lempicka, we have two recommendations that may interest you. Both books will give you even more insight into this artist’s life and work.

Tamara de Lempicka: A Life of Deco and Decadence (1999) by Laura Claridge

Tamara de Lempicka, an Art Deco artist, lived a life well worth documenting as a Jazz Age legend. However, no one has chronicled the narrative of this woman of great brilliance and recognition until now. She was a remarkable attractiveness, an elite Russian Revolution exile, and an openly sensual artist who concentrated on Renaissance aesthetics, imagery, and painterly technique in modern art. The sky-high sums linked to her paintings in recent years haven’t erased the doubts that a woman of Lempicka’s attractiveness and reputation might be a really professional painter.

- A critical biography of a woman of extraordinary talent and notoriety

- With exclusive information on the life and archives of the artist

- A fascinating narrative about the life and work of de Lempicka

Tamara De Lempicka: The Queen of the Modern (2011) by Gioia Mori

The authoritative collection on the first female artist to achieve celebrity. Tamara de Lempicka, global painter, and star of the art deco-style produced paintings that became icons of a period, the “crazy” 1920s and 1930s. She was arguably the most talented exponent of the time. Tamara, spurred by an iron resolve to succeed, not only developed her creative skill, but she also intentionally constructed a persona, that of an exquisite and intelligent woman, the opulent heroine of European luxurious lifestyle.

And with that, we have come to the end of our biographic look into the art and life of Tamara de Lempicka. Maybe most significant was Lempicka’s aim to use her social contacts to carve out a position for her portraits, which mostly portrayed wealthy cosmopolitan characters. The Art Deco style, which was more extravagant but less visually complicated than its forerunner, Art Nouveau, was most likely the right medium for her fashionable style. Most significantly, given its ornamental aspect, her work gave her an opportunity for unusual self-expression: a true result of her epoch, the hedonistic golden period between both the world wars, Lempicka, openly bisexual, made brazen, free feminine sensuality the crux of her artwork.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Style Did Tamara de Lempicka Paint In?

Lempicka was equally fond of art and upper-crust society. She is well-known for her Art Deco aesthetic, which exuded cool sophistication and beautiful sensuality. Her specialty was portraits, with stylized individuals adorned with alluring materials and drenched in a favorable light. Her style was easily identifiable.

Was Tamara de Lempicka Lesbian?

Tamara de Lempicka was known to have had relationships with both males and females. Therefore, she was bisexual, which was considered very scandalous for the era in which she lived. She was also regarded as a proto-feminist who opened the doors for the expression of female sexuality and liberation from dependence.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Tamara de Lempicka – Exploring the Life and Art of Tamara de Lempicka.” Art in Context. January 16, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/tamara-de-lempicka/

Meyer, I. (2022, 16 January). Tamara de Lempicka – Exploring the Life and Art of Tamara de Lempicka. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/tamara-de-lempicka/

Meyer, Isabella. “Tamara de Lempicka – Exploring the Life and Art of Tamara de Lempicka.” Art in Context, January 16, 2022. https://artincontext.org/tamara-de-lempicka/.