“Guernica” by Picasso – Denouncement of the Horrors of War

Picasso’s Guernica painting is considered by many to be one of the most important pieces from the art of wartime. The Guernica by Picasso is a Spanish civil war painting, but why did Picasso paint Guernica in the first place? If you are wondering what the Guernica meaning is, and want to learn more about this fascinating artwork, then read on.

The Story of Picasso’s Guernica Painting

Picasso created the Guernica painting at his Parisian residence in reaction to the bombing of Guernica, a town in northern Spain, at the suggestion of the Spanish Nationalists on the 26th of April 1937. Guernica by Picasso depicts the anguish caused by chaos and violence. It was completed and displayed at the Spanish pavilion at the Paris International Exposition in 1937, as well as at other locations around the globe.

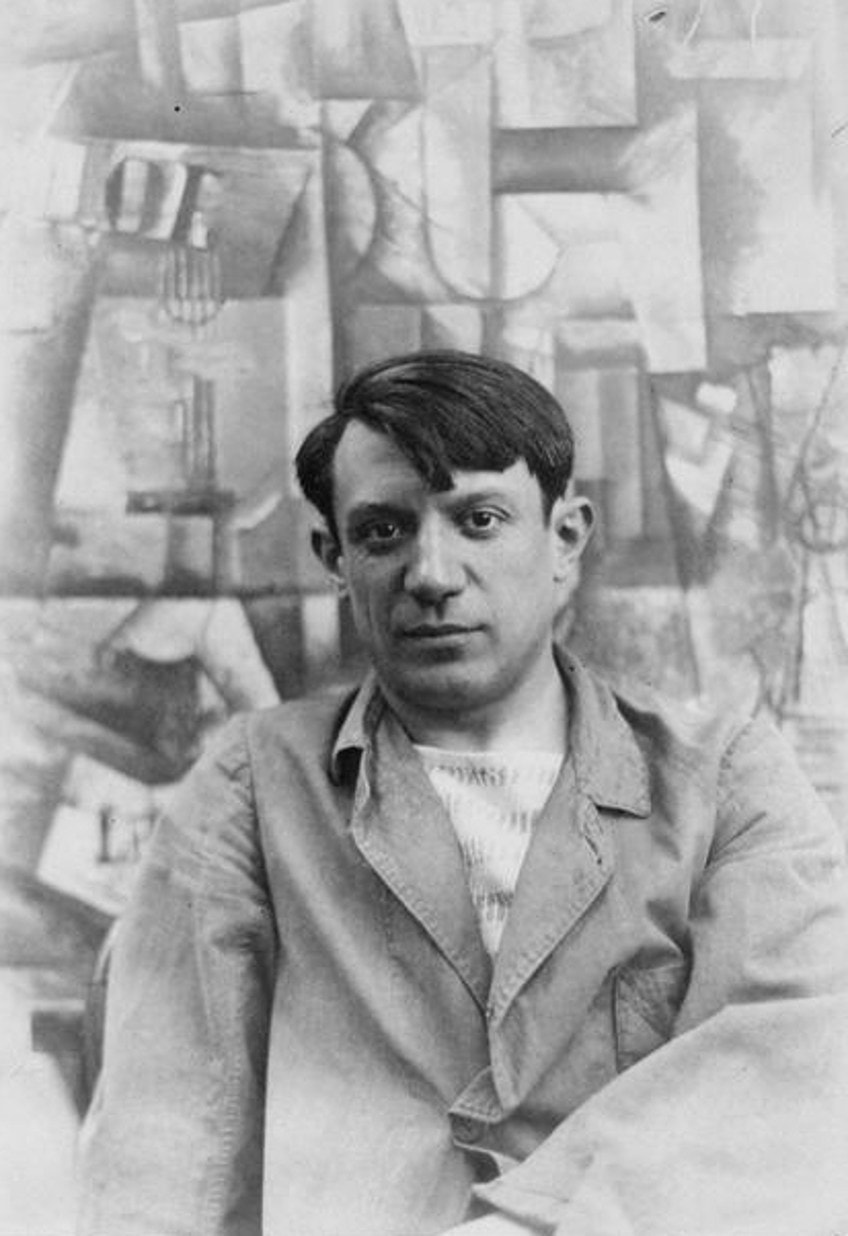

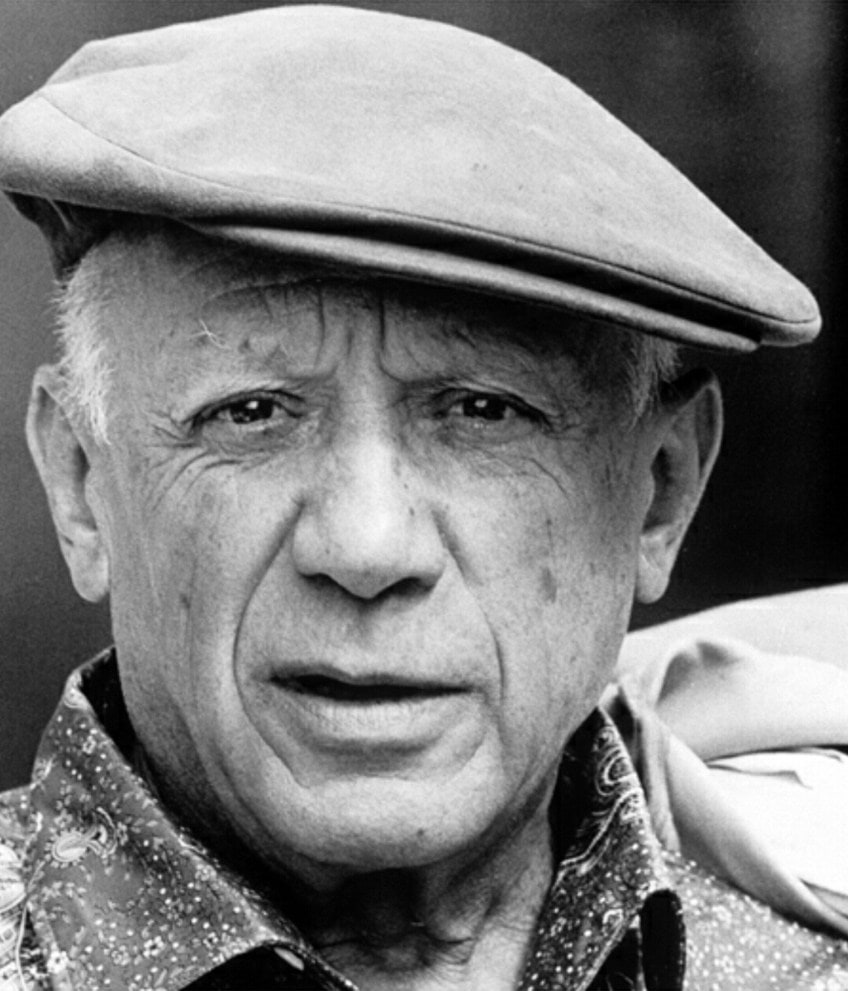

First off, let us look at the creator of the artwork, Pablo Picasso.

A Brief Look at Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973)

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Date of Birth | 25 October 1881 |

| Date of Death | 8 April 1973 |

| Place of Birth | Malaga, Spain |

Picasso had become the artistic genius against which most others evaluated their creative ability throughout the 20th century after fracturing figurative tradition via cubism, which he established with Georges Braque. Picasso, the child of an artist, was born in Malaga in 1881 and attended art schools in Spain. In his late teens, he associated his sentiments with bohemian artists and writers in Madrid and Barcelona who were in opposition to Spain’s stagnated hierarchical structures and conservative cultural identity.

Picasso started to discover his very own vision after being influenced by global concepts such as El Greco’s distraught, altered figures, the gloomy, dark outlines of symbolism, and the serpentine curving of Art Nouveau, to mention only a few.

The art he created in the ten years between 1905 and 1915 released a deluge of distinctiveness – the Rose and Blue Period pieces that probed the interpersonal depths of his life observations and identification; mask-like portrayals and heavily intricate nudes that translated traditional and raw facets of antiquity, Iberian, and African civilizations, ultimately resulting in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907; as well as the cubist and collage artworks that, through their breakdown of illusionism, conveyed Picasso’s breakthroughs.

Picasso was a prolific artist who lived a long life.

In the years following 1915, he integrated decorativeness into his Cubist works and explored broad concepts – particularly the erotic surrender advocated by the Surrealists – in a wide assortment of mediums, including outfit and theater designs, sculptures, prints, ceramics, watercolor paintings, and public works. He also started working on image suites that explored aspects of the creative process such as the artist’s workshop and the relationship between painter and model.

Analyzing Picasso’s Guernica Painting

| Date Completed | 1937 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 250 cm x 776 cm |

| Current Location | Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain |

This famous Spanish Civil War painting was produced in black, white, and gray. A bull, a disemboweled horse, shrieking women, a mutilated army officer, a deceased baby, and burning fire are prevalent in the art of war painting. The painting quickly became popular and enjoyed widespread acclaim, and it managed to bring the Spanish Civil War to the world’s attention.

Commission

While Pablo Picasso was residing at Rue des Grands Augustins in Paris in January 1937, he was hired by the Spanish Republican ruling party to make a massive work of art at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair for the Spanish pavilion. This piece was designed to increase awareness of the conflict and raise funds for it.

From January to late April, Picasso started working somewhat detachedly on the project’s preliminary drawings, which illustrated his longstanding theme of an artist’s workshop.

Then, as soon as he heard about the bombing of Guernica, poet Juan Larrea went to Picasso’s house to persuade him to make the bombing the topic of his piece. Days later, Picasso read George Steer’s account of what happened and relinquished his original plan. Picasso started drawing a series of preparatory sketches for Guernica in response to Larrea’s suggestion.

Historical Context

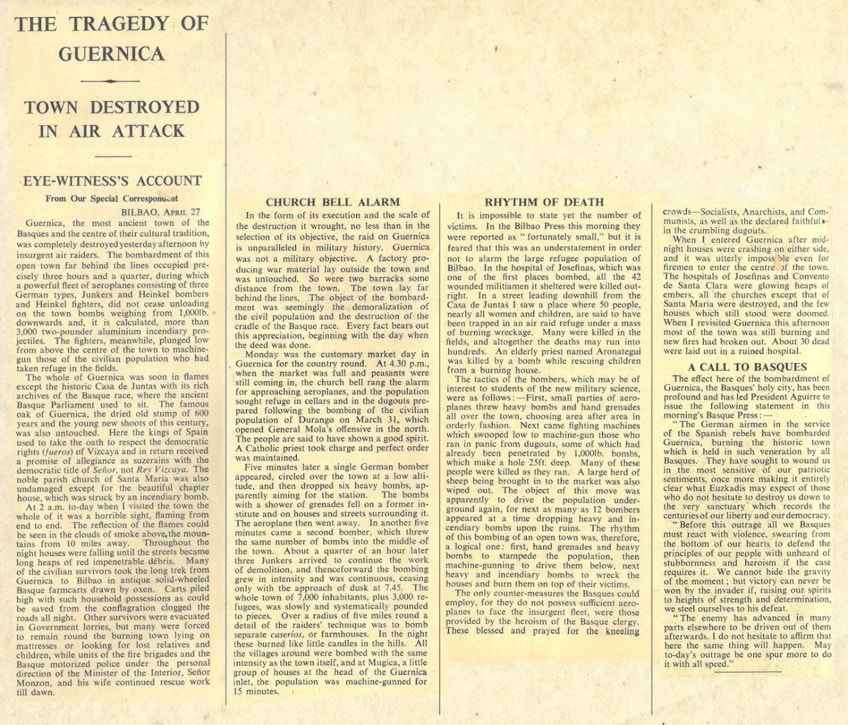

During the Spanish Civil War, the Republican troops were comprised of a variety of factions, including socialists, communists, anarchists, and others with opposing ideologies. Nonetheless, they were aligned in their resistance to the Nationalists who aspired to restore pre-Republican Spain centered on justice, order, and conventional Catholic values. Guernica was regarded as the northern bulwark of the Republican resistance group and the hub of Basque culture. This increased its importance as a threat.

On the 26th of April, 1937, airplanes of the Nazi Germany Condor Legion, bombarded Guernica for almost two hours.

When the very first Junkers squadron came, there was already smoke around; nobody could distinguish the targets of highways, bridges, and suburbs, so they simply dropped everything into the middle. The 250s knocked down many houses and wrecked the water mains. Incendiaries might now spread and become powerful.

The materials used in the dwellings, including tile roofs, wooden porches, and half-timbering, ended in total devastation.

The bulk of the residents was away on vacation, and the vast majority of the remaining residents fled the town as soon as the bombing began. A tiny number of people died in bombed-out shelters. According to some stories, because it was Guernica’s market day, the town’s population gathered in the heart of town. They were unable to flee when the shelling began because the roads were littered with rubble and the crossings going out of town had been damaged.

Guernica was a peaceful community located 10 kilometers from the front lines and halfway between the front lines and Bilbao, the capital of Biscay. However, any Republican withdrawal to Bilbao, or any Nationalist advance to Bilbao, had to pass via Guernica. The nearest significant military target was a war goods plant on Guernica’s outskirts, although it escaped the onslaught unharmed.

As a result, the act was generally criticized as a terrorist bombing.

Because the bulk of Guernica’s males were abroad fighting for the Republicans, the town was largely occupied by children and women at the time of the bombardment. The children and women make Guernica the picture of a victimized, vulnerable humanity. In addition, Picasso frequently depicted women and children as the pinnacle of humanity. An attack on children and women, in Picasso’s opinion, strikes at the heart of humanity.

Creation

Guernica was produced using a matte home paint that Picasso had specifically prepared to have the least amount of gloss imaginable. American artist John Ferren aided him in creating the huge painting, while photographer Dora Maar, who had been shooting Picasso’s workshop and taught him the method of camera-less photography since mid-1936, chronicled its construction.

According to art historian John Richardson, Maar’s images “helped Picasso to abandon color and give the piece the black-and-white intensity of a photograph.”

Picasso, who seldom let strangers inside his workshop to witness his work, permitted powerful guests to witness his progression on Guernica, hoping that the notoriety would benefit the antifascist cause. Picasso remarked while he worked on the painting, “The Spanish conflict is a war of retaliation against the people, against liberty.” My entire career as a painter has been a constant war against response and the death of art. How could anybody believe for a second that I would agree with violence and death?”

Composition

The scenario takes place in a chamber where a wide-eyed bull with a tail that resembles billowing smoke looms over a weeping mother clutching a dead kid in her arms. A horse collapses in anguish in the midst of the room, a massive gaping hole in its side as if it had been run through by a lance or spear. The horse looks to be sporting chain mail armor with rows of vertical tally markings. Under the horse is a dead soldier.

His cut right arm’s hand grasps a shattered sword from which a flower emerges, and the open palm of his left hand has a stigma, a martyrdom emblem drawn from Christ’s stigmata.

Over the suffering horse’s head, a naked light bulb in the form of an all-seeing eye blaze. The face and outstretched right arm of a terrified female appear to have drifted into the room via a window to the horse’s top right, and she watches the tragedy. She holds a flame-lit lamp in her right hand, close to the naked bulb. An astonished woman stumbles towards the middle from the right, underneath the witness, staring blankly into the flaming light bulb.

Roaring daggers have substituted the tongue of the horse, the bull, and the bereaved lady. A dove emerges on a broken wall to the bull’s right, through which dazzling light from the outside shines. On the far right, a fourth lady is imprisoned by fire from above and below, her arms outstretched in horror, her huge open mouth and thrown back head mimicking the sobbing woman’s. Her right hand is shaped like an aircraft. The right side of the space is defined by a dark wall and an open entrance.

This painting contains two “hidden” pictures generated by the horse: The horse’s nostrils and top teeth can alternatively be perceived as a human head turned to the left and slightly downwards.

From beneath, a bull looks to gore the horse. The bull’s head is mostly made of the horse’s whole front leg, with the knee on the ground. The nose of the head is formed by the knee cap of the leg. Within the horse’s breast, a horn emerges. The bull’s tail appears to be aflame with smoke rising from it, seen in a window produced by the lighter gray around it.

Interpretations and Symbolism

The explanations of Guernica differ greatly and conflict with one another. This includes the mural’s two prominent motifs, the bull, and the horse. Patricia Failing, an art historian, stated, “The bull and the horse are significant figures in Spanish culture. Picasso surely employed these figures to perform a variety of roles during the course of his career. This has made deciphering the particular significance of the bull and the horse extremely difficult. Their connection is a type of ballet that Picasso imagined in many ways throughout his career.”

Picasso explained the motifs of Guernica by saying, “This bull is a bull, and this horse is a horse.” If you put significance to certain things in his works, it may be quite real, but it is not his idea. What thoughts and conclusions you have, he has as well, but naturally and subconsciously.

He creates the painting for the sake of the painting. He depicts the items as they are.

According to historian Beverly Ray, the form and body position of the bodies convey protest; Picasso utilizes black, white, and gray colors to establish a mournful mood and convey distress and chaos; flaming structures and collapsing walls not only convey the damage of Guernica but also represent the devastating capabilities of civil war; the daily paper print used throughout the artwork conveys how Picasso managed to learn of the tragedy.

According to Alejandro Escalona, the commotion appears to be unfolding in close quarters, causing a strong sense of tyranny. There’s no way out of this nightmare of a city. The lack of color heightens the horror of the terrible incident unfolding right before your eyes.

You’re taken aback by the blacks, whites, and grays, especially because you’re used to seeing battle scenes aired live and in high-definition straight into your living room.

Wehmeier interprets Guernica as self-referential content in the custom of atelier works of art such as Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656). He achieves this by drawing focus to a multitude of early studies – the so-called primary proposal – that demonstrates an atelier set-up integrating the central triangle shape that resurfaces in the final version of Guernica.

Picasso appears to be attempting to clarify his function and status as an artist in the face of social violence and brutality in his chef-d’oeuvre. Guernica, far from being only a political picture, should be viewed as Picasso’s reflection on what art can genuinely offer to the self-assertion that liberates and shields every human being from overpowering forces such as criminal offense, warfare, and death.

Significance and Legacy

Guernica became an emblem for Spaniards in the 1970s of both the end of the Franco dictatorship following Franco’s death and of Basque nationalism. The image has been used several times by the Basque left. The group Etxerat, for instance, employs a reversed representation of the lamp as their symbol. Guernica has subsequently become a ubiquitous and powerful emblem, warning mankind of the misery and devastation caused by conflict.

Because there are no explicit allusions to the specific event, the message is global and timeless.

In Guernica, Picasso pioneered a new language by blending expressionistic and cubist methods. Guernica, according to Sandberg, transmitted an expressionistic message in its attention to the inhumanity of the airstrike while utilizing cubist terminology. The work’s distinctive cubist quality, according to Sandberg, was its use of diagonals, which left the painting’s context ambiguous and surreal, within and outside at the same time.

In 2016, British art critic Jonathan Jones referred to the work as a Cubist apocalypse, claiming that Picasso “was attempting to convey the truth so viscerally and irrevocably that it might outstare the everyday lies of the age of tyrants.”

Exhibition

Guernica was first seen in July 1937 in the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris International Exposition. The Pavilion, which was supported by the Spanish Republican government during the civil war, was created to depict the Spanish government’s battle for survival, which ran counter to the Exposition’s technical theme. It received little notice when it was unveiled at the painting’s Paris exhibition.

The picture elicited a mixed reception from the general audience. One of the authorities in charge of the Spanish pavilion, Max Aub, was forced to defend the piece against a party of Spanish officials who disagreed with the mural’s Modernist style and tried to replace it with a more traditional artwork commissioned for the show.

Today, we have learned more about “Guernica” by Picasso. The massive image is meant as a massive billboard, a testament to the horrors of the Spanish Civil War, and a forewarning of what was to come in the Second World War. The subdued colors, the intensity of each theme, and the way they are expressed are all vital to the tremendous sorrow of the scenario, which would become the icon for all of contemporary society’s tragic catastrophes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Did Picasso Paint Guernica?

When he learned about the bombing of Guernica, poet Juan Larrea rushed to Picasso’s house to convince him to make the attack the subject of his work. After reading George Steer’s narrative of what transpired, Picasso abandoned his initial intention. In response to Larrea’s idea, Picasso began a series of preliminary sketches for Guernica.

What Is the Guernica Meaning?

The town of Guernica was regarded as the northern bulwark of the Republican resistance group and the hub of Basque culture. It was seen as a threat and was bombed. Picasso created the painting to raise awareness of this tragedy.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““Guernica” by Picasso – Denouncement of the Horrors of War.” Art in Context. May 18, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/guernica-by-picasso/

du Plessis, A. (2022, 18 May). “Guernica” by Picasso – Denouncement of the Horrors of War. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/guernica-by-picasso/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““Guernica” by Picasso – Denouncement of the Horrors of War.” Art in Context, May 18, 2022. https://artincontext.org/guernica-by-picasso/.