Famous Vanitas Paintings – A Look at the Best Vanitas Artworks

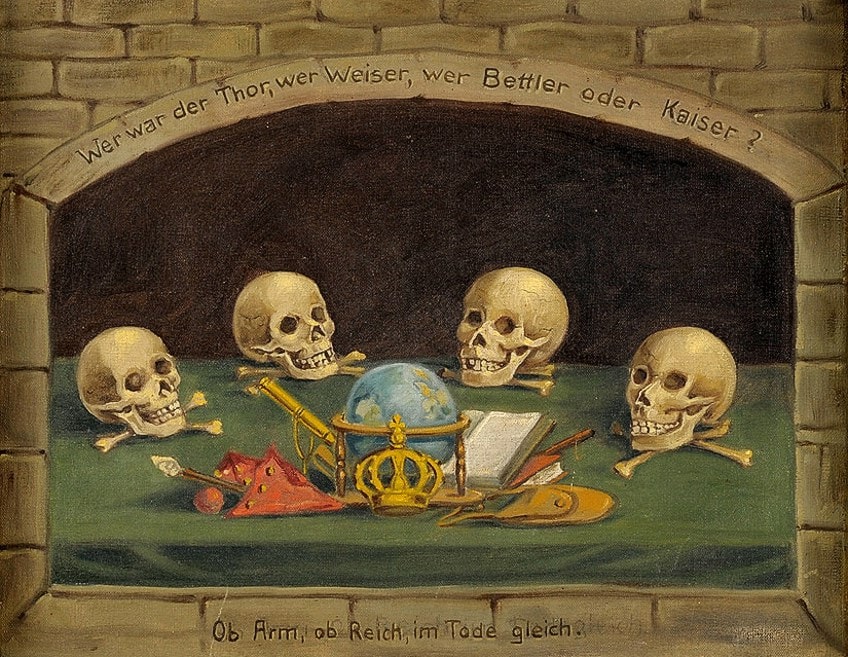

In Europe throughout the 17th century, a gloomy type of still-life painting thrived known as Vanitas artwork. These works were loaded with Vanitas symbols meant to underline the fleeting nature of life, the absurdity of worldly pleasure, and the futile pursuit of status and fame. Vanitas artists produced these still-life paintings to portray to the viewer a sense of how temporary our existence is.

The Meaning of Vanitas

What is Vanitas artwork? Vanitas is closely tied to the older style of memento mori – which translates to “do not forget you shall die”- paintings meant to inspire spectators to reflect on their impermanence. In 15th-century Europe, memento mori began to emerge on the backs of portraits, frequently with skulls depicted inside a gap and coupled with an admonitory saying.

This phrase would advise the client that, while they may wish to have their beauty preserved, the best way to ensure their spirit’s survival in the hereafter is to live a good life.

In the 17th century, Vanitas artworks became fashionable amongst Dutch master painters. Famous Vanitas paintings were produced during a period of theological strife as a bastion for the Protestant goal of contemplating the self. Casting off their Catholic Spanish masters, the Dutch Republic had emerged as a triumphant protestant state, and Vanitas artists attempted to reflect this attitude via these Vanitas artworks.

Famous Vanitas Paintings

Famous Vanitas paintings are subtle and rich in details. They are filled with Vanitas Symbols, which compels the observer to examine the imagery. We constantly see something fresh when we revisit Vanitas artwork. Nevertheless, what Vanitas artists essentially sought to express is a harsh reality. It is certain that we shall die, thus we should think about our goals and everyday routines. The meaning of Vanitas is to act as a reminder to us of the hopelessness of our earthly endeavors in the midst of our mortality.

The Ambassadors (1533) by Hans Holbein the Younger

| Date Completed | 1533 |

| Medium | Oil on Oak |

| Dimensions | 207 cm x 209 cm |

| Current Location | The National Gallery, London |

This enormous Vanitas artwork by Hans Holbein, the most talented 16th-century painter of portraits, does more than only highlight the sitters’ riches and rank. It was produced at a period of theological instability in Europe when the King of England was about to secede from the Roman Catholic Church since the pope refused to annul his union to his first wife.

The things on the table appear to hint at the political complications.

It’s also an outstanding example of the Vanitas artist’s ability to compose pictures and use oil paint to produce a range of textures. During his second voyage to England in the early 1530s, Hans Holbein created this picture. He was laboring on it in 1533, as evidenced by the date beneath his autograph on the ground behind the image on the left.

The Vanitas artist did not frequently sign his canvases, and the autograph here is more complex than previously known examples, implying that he was very pleased with this piece. Henry wedded his second wife the same year the portrait was created. By doing so, he avoided papal jurisdiction, established the Church of England as autonomous of Rome, and appointed himself its leader.

The table also provides space for a variety of things to be displayed. Objects such as musical instruments, money, literature, or blossoms were frequently incorporated in Renaissance portraiture, complementing the sitter’s representation by hinting to their interests, intelligence, education, relationship status, or theological ardor.

These artifacts have been understood together as a graphic essay on the theological and social upheavals in mid-16-century Europe.

Vanitas Self-Portrait (1610) by Clara Peeters

| Date Completed | 1610 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 37 cm x 50 cm |

| Current Location | Private Collection |

In the ever-present passage of time, an instant is recorded and frozen in this Vanitas self-portrait of the artist. We’ve entered what looks to be a wealthy woman’s bedroom, which can be assumed to belong to Clara Peeters. We can see from the luxurious objects gracing the table that she has no desires. Her face is flushed with displeasure, her head tilted as if to protest, “What is so essential that you had to disturb me?”

Her expression also says that she is tired, almost melancholy, with all the world’s joys and nevertheless she is still dissatisfied.

The wealth and jewelry are scattered about haphazardly and carelessly; she has far more than she requires. The source of light appears to be emanating from the left, maybe from a window. Maybe she hasn’t acknowledged us at all and is just staring out the window, bored with her baubles and things.

The light catches the silver coins on the tabletop and casts a soft shimmer on the candle holder, which is leaning on its side. A bouquet of flowers gives this painting some vitality and enhances it considerably. However, take note of the blossom on the far right of the arrangement. It’s saggy and seems to be dying.

This less-than-subtle Vanitas symbolism alludes to the passing of time and the eventual disintegration of all living organisms, including the female in the image.

This Vanitas artwork implies the transience of all worldly things and pleasures. These ephemeral objects are ultimately worthless, useless, and, in the greater scale of things, an impediment to the sanctity of the soul.

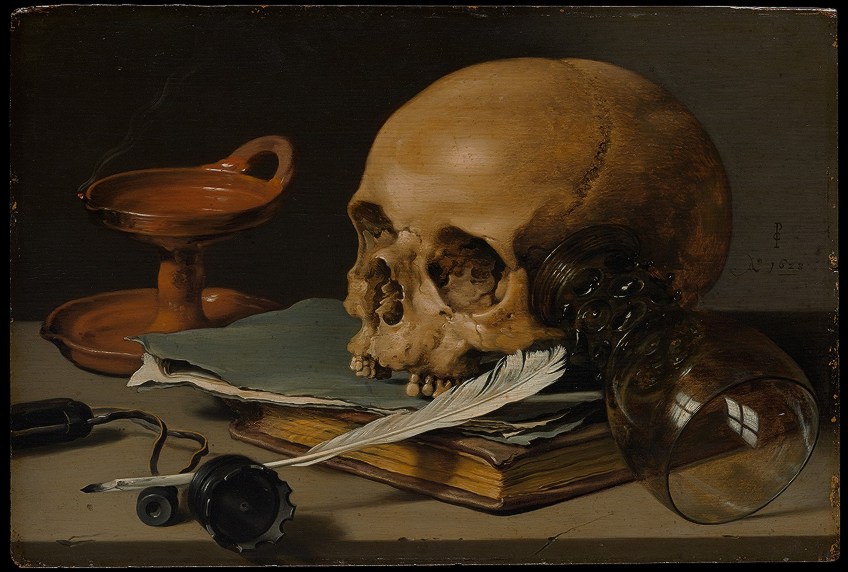

Still Life with a Skull and a Quill (1628) by Pieter Claesz

| Date Completed | 1628 |

| Medium | Oil Painting |

| Dimensions | 24 cm x 35 cm |

| Current Location | The Metro Museum of Art |

This is one of the first documented still lifes by Piter Claesz, a Dutch artist who gave everyday objects great individuality. A skull, a spilled glass with ephemeral reflections, an extinguished light, and a writer’s tools all imply that worldly endeavors are eventually futile. Claesz progressively refined the clarity and incisiveness acquired in this piece over a period of many years, during which he may be considered to have achieved an early maturity.

The theme might be read as one of many versions on the theme of earthly achievements, study, indulging in the arts—that eventually amount to nothing: everything is an illusion.

The puff of smoke in the lantern and the reflection in the glassware is typical of Dutch artworks of transitory life. The cranium is not only an incursion into the domain of human activities here; it is a known feature of a teacher or thinker. For the previous purchaser of a piece like this, the picture most likely reflected not just the vanity of information but also the vanity of wisdom.

This would have been much like a contemporaneous portrait of a figure clutching a skull expressed the sitter’s conviction in a metaphysical existence in the afterlife.

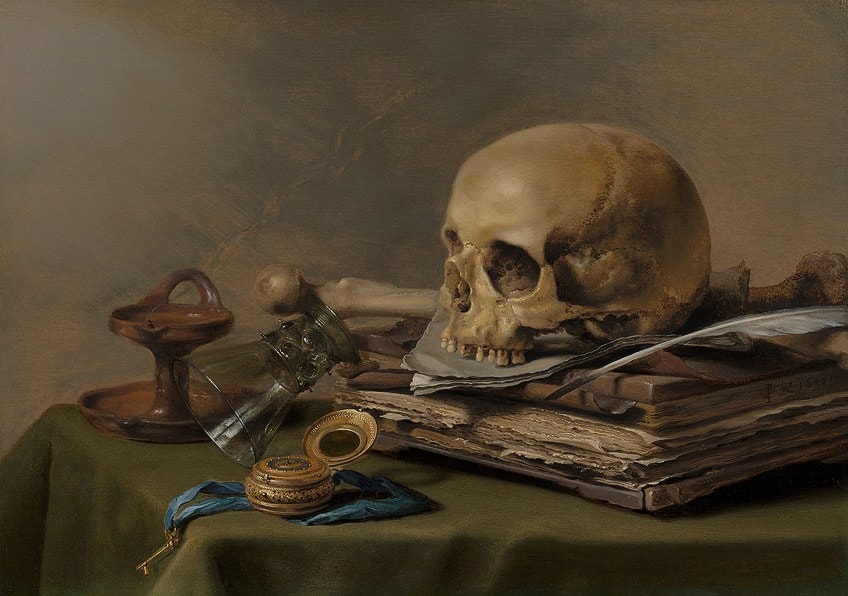

Vanitas Still Life (1630) by Pieter Claesz

| Date Completed | 1630 |

| Medium | Oil on Wood Panel |

| Dimensions | 39 cm x 56 cm |

| Current Location | Mauritshuis, The Hague |

The lifelike portrayals of the things in vanitas artworks have metaphorical importance, informing the observer of the fleeting reality of existence. Throughout the Dutch Golden Age, these paintings served as moral instruction in accordance with the beliefs of Protestant Calvinism in the northern parts of the Netherlands. The iconography of Vanitas Still Life by Pieter Claesz is packed with symbolism: the gilded timepiece, the emptied upturned glass, the cranium, and the extinguished oil lamp all refer to mortality.

All of these items warn the observer of the vanity and pointlessness of worldly commodities and belongings.

A 17th-century spectator would have regarded this as a warning about the time’s prosperity and rising consumerism. The puff of smoke in the backdrop, implying that the light of the oil lamp has just been extinguished, conveys a feeling of urgency over the unavoidable passage of time. The positioning of the source of light on the left of Vanitas Still Life by Pieter Claesz highlights the items, emphasizing their symbolic content.

The monochromatic backdrop, as well as the controlled and muted color palette of browns and creamy tones, do not interfere with the Vanitas artist’s deeper message.

Allegory of Vanity (1633) by Jan Miense Molenaer

| Date Completed | 1633 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 102 cm z 127 cm |

| Current Location | Toledo Museum of Art |

The painting Allegory of Vanity by Jan Miense Molenaer is believed to be an exceptional representation of Vanitas artworks. This painting represents three people: a mother, her child, and her maid. This picture has a number of motifs that relate to concepts of wealth, excess, and happiness. The musical instruments, her ring, the map displayed on the walls in the backdrop, and the clothing the mother and son are sporting all represent these ideals.

Amidst all of this grandeur, the female’s bond with her child conveys a feeling of futility and pointlessness.

While her young child tries to entice her interest, the mother rests and gazes out into the horizon. During this time, she seems to be clutching a mirror and a ring, both of which are added as vanity symbols. It appears that no matter how desperately the youngster tries to entice his mother’s interest, he will be unable to free her from her servitude to the meaninglessness of her life.

The skull on which she puts her feet emphasizes the meaninglessness of existence even more, as it was added as a symbol of impending death and degradation.

Still Life with Oysters (1635) by Willem Claesz

| Date Completed | 1635 |

| Medium | Oil on Panel |

| Dimensions | 87 cm x 112 cm |

| Current Location | Rijks Museum |

Willem Claesz, a Dutch painter, was noted for his innovative still-life paintings, which he produced entirely through his profession. Still Life with Oysters is an interesting spin on Vanitas artworks. This is due to the fact that no clear Vanitas symbols or artifacts are provided.

Claesz, on the other hand, simply showed things of riches, such as shellfish, alcohol, and a metal tazza.

Considering their wealth, these goods look to be in full disorder, since the plates have been flipped and the meal has been hastily left. A delicate Vanitas pattern is symbolized by a peeled lemon, showing the bitterness within, and is claimed to emerge as a metaphorical picture of human avarice.

Furthermore, the oysters look to be devoid of both nourishment and vitality, and the rolled-up bit of paper is taken from a schedule. Both are thought to represent the passage of time. Claesz’s color palette in this artwork is simultaneously gloomy and restricting, which was a popular choice in the bulk of famous Vanitas paintings at the period. These hues were chosen primarily for their somber qualities and capacity to generate a dark atmosphere.

The only source of light featured was used to warn observers of their own approaching demise.

Allegory of Vanity (1636) by Antonio de Pereda

| Date Completed | 1640 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 174 cm x 139 cm |

| Current Location | Kunsthistorisches Museum |

The angel surrounded by magnificent objects in this renowned Vanitas artwork subtly alludes to the meaningless search for power. Cash and expensive jewels are next to her, yet the angel seemed to be unconcerned by her prosperity. It’s as if she realizes the secret message that the picture is attempting to express before the spectators do.

Notwithstanding the timepiece, candle, and skull depicting the eventuality of dying, this artwork does not clearly express to the spectator themes of melancholy and despair.

This might be because the angel is conscious of her impermanence in the normal world, knowing that her existence would be immortal in her hereafter. The angel holding a portrait depicting the King of Spain while gesturing to the world exemplifies the futility of authority once more.

This concept was believed to relate to the absurdity of human attempts such as the divide-and-conquer tactic, which was incorporated in an effort to alert folks about the folly of all of their acts in order for them to cease them.

The Last Drop (1639) by Judith Leyster

| Date Completed | 1639 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 89 cm x 73 cm |

| Current Location | Philadelphia Museum of Art |

Judith Leyster was a very well-established painter throughout the 17th century, but her fame faded soon after her passing. There were no indications of her moniker in purchase documents, and no reproductions of her work were created. Nevertheless, she was acknowledged early in her profession as the very first female painter in the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke.

She was not noticed and recognized as a significant lady in Dutch Golden Age artwork until 1893.

One hidden interpretation for this artwork centers on the erosion of identity and the wasted condition of drinking, in connection to the corpse and the social scenario in The Last Drop. As the skeleton approaches, both men look nonchalant with the actions they are performing. The skeleton’s demeanor and position indicate that it is having as much fun as the inebriated men.

Skeletons were common characters in 17th-century painting, symbolizing the inexorable aspect of dying. The features of the men look to be comparable to those in Judith Leyster’s 1629 painting of the Merry Trio. The Merry Trio and The Last Drop depict nighttime and afternoon, respectively. Merry Trio depicts the initial stage of alcohol, which occurs generally in the evening at sunset. The Last Drop is the phase of the celebration after the drink has progressed; it is now night, and men are overwhelmed by the impact of alcohol. The use of the light between the people and the skeleton represents the night setting.

At this stage in the evening, both men are inebriated and unconscious of the presence of a skeleton between them.

The Penitent Magdalen (1640) by Georges De La Tour

| Date Completed | 1640 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 133 cm x 102 cm |

| Current Location | The Met Museum |

Mary Magdalene, pertaining to the teachings of the Catholic religion in the 17th century, was an instance of a penitent person and hence a representation of the Sacrament of Penance. Mary, tradition has it, led a debauched lifestyle before her sibling Martha encouraged her to hearken to Jesus Christ. She grew to become one of Jesus’s most loyal disciples, and he cleansed her of her previous misdeeds. Mary is depicted in the side view, sitting at a table, in Georges de La Tour’s solemn painting.

The illumination in the arrangement comes from a candle, but the illumination also has a metaphysical connotation since it produces a golden color on the saint’s forehead and the things on the tabletop.

The candlelight casts a shadow on Mary’s left hand, which is resting on a skull resting on a book. In a glass, the cranium is mirrored. The skull and reflection are vanitas symbols, representing the impermanence of existence. The simplified shapes, limited palette, and devotion to details create a melancholy quiet that is distinctive to La Tour’s works.

La Tour’s profound naturalism made religious metaphors approachable to all viewers.

Even though the mood of his artwork is deeply religious, the firmness and massing of the shapes indicate the same stress on precision and proportion that pervades current historical painting and was a trademark of French baroque art.

Vanitas Still Life (1648) by Jan Jansz Treck

| Date Completed | 1648 |

| Medium | Oil on Oak |

| Dimensions | 90 cm x 78 cm |

| Current Location | The National Gallery, London |

A smoldering ember from a long-extinct clay pipe rests on a stone ledge. The pipe extends from an upturned helmet’s open visor and crosses a spilled hourglass. These artifacts are intended to be seen upright; seeing them overturned in this manner is intended to be upsetting. The harsh, white line of the pipe emerging from the dark emptiness of the visor adds to the discomfort. Although it may be a still-life painting, it is not your typical calm arrangement of valuable relics meant for peaceful reflection.

The expensive goods near the helmet draw our focus, yet the obviously unstable placement implies cohesion: there is nothing serene here.

Jan Jansz Treck displays a sparkling Rhenish stoneware wine pitcher and a glossy black lacquered container. Musical instruments – a flute, a viola – and a silk scarf fashioned with beautiful colors and gold and silver embroidery are among the items he has chosen. A line descending from the mouth of the cranium and down through the flute, on the other hand, results in a painting of a man upside down, teetering off the ledge. The scarf is crumpled and on the verge of falling to the ground. This was supposed to be a philosopher’s image, to be investigated, pondered, and understood by those who saw it.

Philosophers would have loved and comprehended how the artist employed lighting and shadows to depict the material of each priceless object, as well as the accuracy and precision of each piece in the picture.

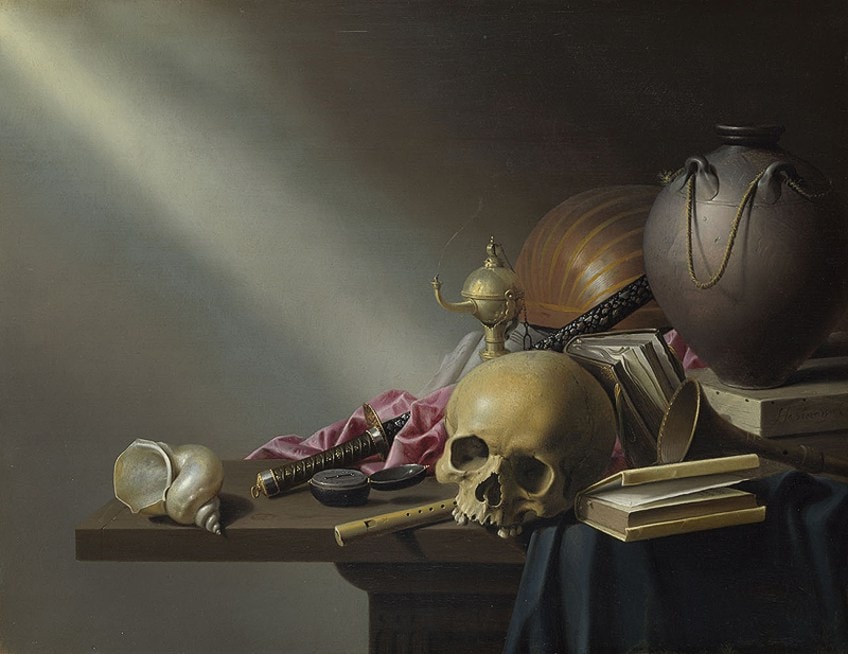

Vanitas Still life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life (c. 1640) by Harmen Steenwijck

| Date Completed | c. 1640 |

| Medium | Oil on Oak |

| Dimensions | 39 cm x 50 cm |

| Current Location | The National Gallery, London |

There’s no dispute about where our attention is focused here. A striking ray of sunshine slices through the shadows to show the skull’s vacant sockets as it lies to one side on the table’s edge. We are gazing down at the image of mortality. But what about the weird array of other items that make up the remainder of this intriguing Vanitas artwork? It’s never clear why the Vanitas symbols represented in the artwork were selected. We do understand that famous Vanitas paintings were prized as proof of an artist’s ability to portray various features.

The texturing and shading of rumpled fabric, as well as the sheen and warped reflection in metals, glassware, woodwork, and seashells, presented an outstanding chance for virtuoso paintings, which were highly regarded at the time.

Harmen Steenwijck appears to have added further elements to heighten the difficulty, such as looping a tattered rope over the grips of the earthenware beaker, folding the pages of one of the novels, and positioning numerous items so that they extend forward over the table’s edge. X-ray photographs of the picture demonstrate that Steenwijck changed the arrangement significantly. The flagon on the side was repainted over a figure of a man with a garland on his head, most likely a Roman emperor, a sign of earthly sovereignty.

We’ll never discover why Steenwijck or his client chose the bust over the skull; possibly the white or stone color of the bust attracted focus away from the cranium. Rather, the flask’s curved contour enhances that of the instrument and the skull’s dome.

Allegory of Human Life (c. 1660) by Joris van Son

| Date Completed | 1660 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 124 cm x 92 cm |

| Current Location | Walters Art Museum |

Exquisite garlands of sensual, delicate petals at the peak of their splendor and fruit ripened to the verge of rupturing, beckoning our touch before their ultimate breakdown frequently represented religiously significant scenes in Flemish 17th-century art. A skull, a flickering candle, and a timepiece frame complement a still life of artifacts emphasizing the shortness of human existence. The human cranium has long been a focus for Flemish artists; indeed, many pious Christians in the 1600s maintained a human head for their personal acts of worship.

The mixture of a skull, candles, and timepiece invites contemplation on the Resurrection of Christ and its pledge of everlasting existence to the devout.

The skull was clearly too much for one previous owner since it had been painted over at some time in the past, only to be uncovered in 1988 after expert study and cleansing. Van Son has added an ear of corn, a New World contribution to the Continental diet, along with flowers and fruits such as rose, grape, cherry, and thorns, along with butterflies and an insect. In 1643, Joris Van Son was appointed master of the Antwerp painters’ guild of St. Luke. He specialized in fruit portions, whether spread out in a tempting presentation on a tabletop or in garlands or wreaths enclosing a nook like this one.

The painter preferred this cartouche style in the 1650s.

Allegory of the Vanities of the World (1663) by Pieter Boel

| Date Completed | 1663 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 207 cm x 260 cm |

| Current Location | Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille |

All through his tenure, Pieter Boel, a prominent Flemish Vanitas artist, excelled in sumptuous still lifes. Because of its meticulousness and exceptionally vast scale, this painting is considered a masterpiece among Vanitas artworks.

When viewing the piece, the audience’s attention is drawn to the baroque majesty evident, as reflected by the enormous symbolic imagery provided.

It depicts art (melodies, sculpting, and artwork), honor (heavy armor, blade, weapons), temporal authority (Secular or Religious crowns), divine energy (headpiece and crucifix), affluence (copper, gold, gems, robes, and valuable fabrics), and wisdom (globe and journals) piled as a tower in a wrecked mansion or chapel.

A crane decorated with laurels rests atop the heap. To the side, an iron amulet with no start or end represents infinity. Several things, like an armor plate and archery darts, allude to the nature of wartime failure.

In juxtaposition to these items, numerous academic Vanitas symbols, such as textbooks and manuscripts, are represented.

The bishop’s hat, crown, topped headdress, and velvet silken gown are all depictions of luxury. While these financial emblems suggest religious and political authority, there is a conflict. The farther one progresses through these artifacts, the more these things remain as a clear reminder that destiny despite everything overcomes all.

Vanitas Still Life with a Crowned Skull (1689) by Evert Collier

| Date Completed | 1689 |

| Medium | Oil on Wood |

| Dimensions | 94 cm x 112 cm |

| Current Location | Met Museum |

Consider Collier’s depiction of a pearl necklace and other treasures streaming out of an open coffin. Next to the coffin is a Nautilus container, so named because it was a bowl constructed from a chiseled and refined nautilus shell and then set by goldsmiths on a slender silver or gold stalk to add to the opulence. A skull topped with a wreath stands in front of the Nautilus goblet. The cranium sits atop an inverted crown, under which are closed pumps and a studded sword blade. The sword’s handle captures a message on the table’s edge.

The message’s Latin text serves as a warning: “No one may be termed joyful before dying.” It’s a caution not to name someone fortunate or joyful until he’s tasted everything life has to deliver.

A smoldering candle wrapped in ivy is resting on the tabletop behind the casket, though it’s difficult to see in the image. An open volume may be seen to the right of the cranium. So, what does it all mean? In a nutshell, our impermanence. The inclusion of the skull serves as a reminder of death and instantly identifies the piece as a vanitas artwork. However, this sculpture contains more significance than only the skull signifying death.

If you hope to complete craft projects where you need paint that will work well for any number of surfaces, then craft paint is your go-to! The consistency is smooth, creamy, and easy to use.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Vanitas?

Vanitas is a type of art that focuses on death. It is a sub-category of memento mori artwork. Through this artwork, Vanitas artists were able to communicate that life was short and that trying to live life solely to achieve fame and recognition was a hollow and empty desire. The first of these paintings appeared on the back of portraits to remind the person who ordered the paintings that capturing their appearance did not stop the inevitable march of death.

What Is the Meaning of Vanitas?

A vanitas is a metaphoric piece of art that depicts the fleetingness of existence, the waste of enjoyment, and the inevitability of demise, frequently juxtaposing images of prosperity with symbols of fragility of life and mortality. Vanitas still lifes, a popular genre in the Low Countries during the 17th centuries, are the most well-known; nevertheless, they have also been made at other eras and in various mediums and genres. The word vanitas implies ‘blankness,’ ‘pointlessness,’ or ‘unworthiness,’ and the conservative religious view is that worldly possessions and endeavors are fleeting and meaningless. It refers to biblical scripture, in which vanitas represents the Hebrew term hevel, which also encompasses the notion of transitoriness.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Famous Vanitas Paintings – A Look at the Best Vanitas Artworks.” Art in Context. November 2, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-vanitas-paintings/

Meyer, I. (2021, 2 November). Famous Vanitas Paintings – A Look at the Best Vanitas Artworks. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-vanitas-paintings/

Meyer, Isabella. “Famous Vanitas Paintings – A Look at the Best Vanitas Artworks.” Art in Context, November 2, 2021. https://artincontext.org/famous-vanitas-paintings/.